Miwok is a word meaning “People” in Miwokan.

Location The Miwok were originally composed of three divisions: Eastern (Sierra), Lake, and Coast. The Miwok lived in over 100 villages along the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers, from the area north of San Francisco Bay east into the western slope of the Sierra Nevada. The Lake Miwok lived near Clear Lake, north of San Francisco Bay.

Today the Eastern Miwok live in five rancherias, located roughly between Sacramento and Stockton, and in nearby cities. Lake Miwoks have one small settlement at Middletown Rancheria that they share with Pomo Indians.

Population Miwok population stood at about 22,000 in the eighteenth century, of whom approximately 90 percent (19,500) were Eastern Miwok. In 1990, the total Miwok population was about 3,400.

Language There were several dialects and groups of Miwokan, a California Penutian language.

Historical Information

History Lowland occupation of California by the Eastern Miwok probably began as early as 2,000 years ago or more; occupation of the Sierra Nevada is only about 500 years old. The Eastern Miwok were divided into five cultural groups: Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Miwok, Southern Miwok, and Central Sierra Miwok. Sir Francis Drake (1579) and Sebastian Cermeno (1595) may have met the Coast Miwok, but no further record of contact exists until the late eighteenth century and the beginning of the mission period. Russians also colonized the region in the early nineteenth century.

The Spanish had established missions in Coast Miwok and Lake Miwok territory by the early nineteenth century to which thousands of Miwoks were forcibly removed and where most later died of disease and hardship. In the 1840s, Mexican rancheros routinely kidnapped Lake Miwok people to work on their ranches and staged massacres to intimidate the survivors. As a result of all this bloodshed, previously independent tribelets banded together and even formed military alliances with other groups such as the Yokuts, raiding and attacking from the 1820s through the 1840s.

Everything changed for the Eastern Miwok in the late 1840s, when the United States gained political control of California and the great gold rush began. Most Miwoks were killed by disease, white violence, and disruption of their hunting and gathering environment. The Mariposa Indian War (1850), led by Chief Tenaya and others, was a final show of resistance by the Eastern Miwok and the Yokuts against Anglo incursions and atrocities. By the 1860s, surviving Miwoks were eking out a living by mining, farm and ranch work, and low-paying work on the edges of towns. Most Miwoks remained on local rancherias, several of which were purchased for them by the U.S. government in the early twentieth century.

Coast Miwok remained for the most part in their traditional homeland in the twentieth century, working at sawmills, as agricultural laborers, and fishing. They were officially terminated in the 1950s, but in 1992 a group called the Federated Coast Miwok created by-laws and petitioned the government for recognition.

Religion Eastern and probably also Coast Miwoks believed in the duality (land and water) of all things. Ceremonies, both sacred and secular, abounded, accompanied by dances held in great dance houses. The ceremonial role of each village in the tribelet was determined by geographical and political considerations. Lake Miwoks only allowed men in the dance houses.

Sacred ceremonies revolving around a rich mythology featured elaborate costumes, robes, and feather headdresses. The Miwok recognized several different kinds of shamans, such as spirit or sucking shamans, herb shamans (who cured and helped ensure a successful hunt), and rattlesnake, weather, and bear shamans. Shamans, whose profession was inherited patrilineally, received their powers via instruction from and personal acquisition of supernatural power gained through dreams, trances, and vision quests.

Government The main political unit was the tribelet, an independent and sovereign nation of roughly 100-500 people (smaller in the mountains). Each tribelet was composed of a number of lineages, or settlement areas of extended families. Larger tribelets, those composed of several named settlements, were led by chiefs, who were usually wealthy. Their responsibilities included hosting guests, sponsoring ceremonies, settling disputes, and overseeing the acorn harvest. In turn, chiefs were supplied with food and were expected to conduct themselves with a measure of grandness.

Among the Lake Miwok, special ceremonial officials presided over dances. Among Eastern and Lake Miwok the office of chief was hereditary and was male if possible. Other officials included the announcer (elective) and messenger (hereditary). The Coast Miwok also included two important female officials who presided over certain festivals and who supervised construction of the dance house.

Customs All Eastern Miwoks were members of one of two divisions (land or water). Both boys and girls went through puberty ceremonies. Marriage between Lake Miwok was a matter arranged by the parents through gift giving. Intermarriage between neighboring groups was common. The many life-cycle prohibitions and taboos included sex before the hunt or during a woman’s period. Fourth and later infants may have been killed. The dead were cremated or buried. Widows cut their hair and rubbed pitch on their heads. Along the coast, property was burned along with the body. The name of the dead was never spoken again. There were no mourning ceremonies.

Men and occasionally women used pipes to smoke a gathered local tobacco. Miwoks possessed a strong feeling for property: Trespass was a serious offense, and virtually every transaction between two people involved payment. The profession of "poisoner" was widely recognized, and many people feared being poisoned more than they feared illness. People often danced, both for fun and ritual. Most songs were considered personal property. Both sexes played hockey, handball, and the grass game. Women also played a dice game. Children played with mud or stick dolls, acorn buzzers, and pebbles as jacks.

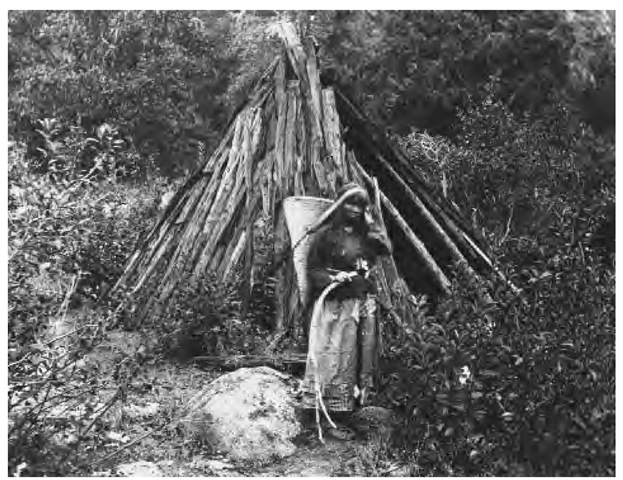

Dwellings Miwoks built conical houses framed with wooden poles and covered with plants, fronds, bark, or grasses. Hearths were centrally located, next to an earth oven. Pine needles covered the floors; mats and skins were used for bedding. Some winter homes or dance houses, and most houses among the Lake Miwok, were partially below ground. Larger villages had a sweat lodge that served mostly as a male clubhouse.

Diet Acorns, greens, nuts, berries, seeds, and roots were some of the great variety of wild plants eaten by the Miwok. They also ate fish, especially salmon, trout, and shellfish, and hunted elk, deer, bear, antelope, fowl, and small game, especially rabbit. Deer were hunted in several ways, including driving them into a net or over a cliff, stalking while in deer disguise, shooting them from blinds, and running them down over the course of a day or so. Miwoks generally avoided eating dog, coyote, skunk, eagle, roadrunner, and snakes and frogs.

The Sierra Miwok and Mono peoples of the Sierra foothills built conical houses framed with wooden poles and covered with plants, fronds, bark, or grasses. Hearths were centrally located, next to an earth oven. Pine needles covered the floors; mats and skins were used for bedding. This photograph shows a woman in front of such a dwelling in 1870.

Key Technology Hunting equipment included traps, snares, and bow and arrow. A variety of baskets served many functions, such as winnowers, seed beaters, cradles, burden baskets, and storage. Fish were caught with nets, hook-and-line, and harpoon. Foods were stored either in granaries (acorns) or baskets. Foods were baked or steamed in earth ovens. Stone and bone provided the raw material for a variety of tools. Cords and string came from plant fibers, especially milkweed and hemp. Coast and Lake Miwok used clamshell beads as money. Musical instruments included elderberry flutes, drums, cocoon rattles, clappers, and whistles. The Lake Miwok used several plants for natural dyes.

Trade Costanoans supplied the Eastern Miwok with salt. Other items of exchange included obsidian, shells, bows, and baskets. Along the coast, goods were more often purchased than traded. Lake Miwoks often traveled west to collect marine resources such as clamshells and seaweed.

Notable Arts Fine arts included baskets and representational petroglyphs, consisting mostly of circles and dots and beginning as early as 1000 B.C.E.

Transportation The Eastern Miwok used a tule balsa on navigable rivers. Log rafts were used on the coast.

Dress Eastern and Lake men wore buckskin breechclouts and shirts. Men along the coast wore little or nothing. Most women wore hide skirts and aprons, although in lower elevations they sometimes used grasses for skirts. Hide and woven rabbit-skin robes and blankets kept people warm in winter. Most people also wore ear and nose ornaments as well as face and body paint. They also practiced tattooing and head deformation (flattened heads and noses) for adornment. Young children wore no clothes. Hair was worn long except in mourning (Eastern Miwok). Lake Miwoks braided their hair.

War and Weapons The bow and arrow was the most important weapon. Coast Miwoks also used slings.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations Middletown Rancheria (189 acres in Lake County; 18 Indians in 1990) is a Lake Miwok and Pomo community. Eastern Miwok lands include Jackson Rancheria (1893; 331 acres in Amador County; 35-40 families in 1990; tribal council), Sheep Ranch Rancheria (1916; .92 acres [a cemetery] in Calaveras County), and Tuolomne Rancheria (1910; 336 acres in Tuolumne County; some 150 population in 1990). Other rancherias with very small Miwok populations include Shingle Springs, Buena Vista, Chicken Ranch, and Cortina.

Economy Many Miwoks work in logging and related industries. There are also some employment opportunities at Yosemite National Park. There is a bingo parlor on the Chicken Ranch Rancheria.

Legal Status The Chicken Ranch Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians, the Jackson Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians, the Tuolomne Band of Me-Wuk Indians, the Sheep Ranch Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians, and the Buena Vista Rancheria are federally recognized tribal entities. The Cortina Indian Rancheria is a federally recognized tribal entity.

The American Indian Council of Mariposa County, the Calavaras Band of Mewuk, the Federated Coast Miwok Tribe, and the Ione Band of Mewuk have petitioned for federal recognition.

Daily Life There is a clinic/health center and a traditional roundhouse at Tuolumne Rancheria. Tuolumne also celebrates an acorn festival as well as a pan-Indian gathering in September. Although most of the religious traditions have been lost, young people are beginning to revive some dances and songs. Many Coast Miwoks have achieved prominence as scholars. Lake Miwoks have developed innovative educational programs in local schools. With native speakers of Miwok almost gone, the people have developed a number of programs to preserve and restore the language. Traditional basket making and weaving are also making comebacks.