Micmac (Mik mak), or Mi’kmaq, "allies." The Micmac called their land Megumaage and may have called themselves Souriquois. They were members of the Abenaki Confederacy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Culturally similar to the Maliseet, Penobscot, and Passamaquoddy, they were known to the seventeenth-century British as Tarantines, possibly meaning "traders."

Location The people were traditionally located in southeast Quebec, the Maritime Provinces, and the Gaspe Peninsula of eastern Canada, a region of forests, lakes, rivers, and a rugged coast. They lived there and in northern Maine in the late twentieth century.

Population The Micmac population was between 3,000 and 5,000 in the sixteenth century. There were approximately 20,000 registered Canadian Micmacs in 1993, including about 15,000 in the Maritimes and 4,000 in Quebec, and several thousand more in the United States.

Language Micmac was an Algonquian language.

Historical Information

History The Micmac were originally from the Great Lakes area, where they probably had contact with the Ohio Mound Builders and were exposed to agriculture. They may have encountered Vikings around 1000. The Cabots, early explorers, captured three Micmacs at their first encounter. Friendly meetings with Jacques Cartier (1523) and Samuel de Champlain (1603) led to a long-term French alliance.

The Micmac were involved with the fur trade by the seventeenth century, becoming intermediaries between the French and Indian tribes to the south. A growing reliance on non-native manufactured metal goods and foods changed their cultural and economic patterns, and war, alcohol, and disease vastly diminished their population. In 1610, the grand chief Membertou converted to Catholicism after being cured by priests.

In the eighteenth century, the French armed Micmacs with flintlocks and encouraged them, with scalp bounties, to kill people from the neighboring Beothuk tribe. This they did to great effect, nearly annihilating those Indians, after which they occupied their former territory in Newfoundland. British attempts at genocide against the Indians included feeding them poisoned food, trading them disease-contaminated cloth, and indiscriminate individual and mass murder.

By the mid-eighteenth century, most Micmacs had become Catholics. They continued fighting the British until 1763. Much of this fighting took place at sea, where the people showed their excellent nautical skills. Following the American Revolution and the end of the fur trade, Micmacs remained in their much-diminished traditional area, which was increasingly invaded by non-natives.

In the nineteenth century, Micmacs were forced to accept non-Indian approval of their leadership as well as a general trimming of lands guaranteed by treaty. The people continued some traditional subsistence activities during the nineteenth century but also moved toward working in the lumber,construction, and shipping industries and as migrant farm labor. They were generally excluded from skilled or permanent (higher-paying) jobs. Starvation and disease also stalked the people during those years.

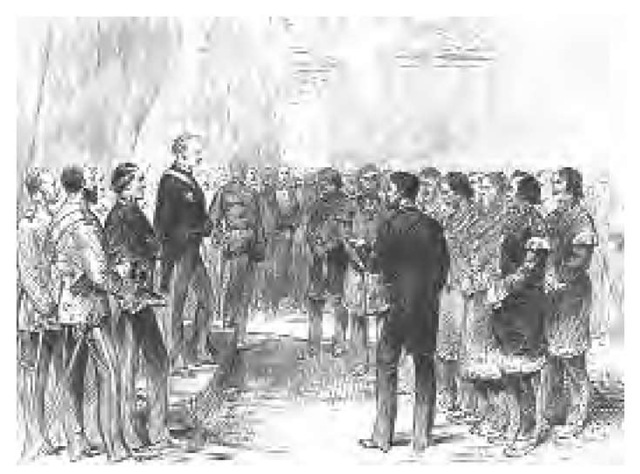

A late-nineteenth-century illustration of a Micmac delegation meeting with Lord Lorne, the governor general of Canada. In the nineteenth century, Micmacs were forced to accept non-native approval of their leadership as well as a general trimming of lands guaranteed by treaty.

Micmacs had lost most of their Canadian reserves by the early 1900s. Schools were located on many of those that remained. Hockey and baseball became very popular before the Depression. Significant economic activities in the early to mid-twentieth century included logging, selling splint baskets, and local seasonal labor, such as blueberry raking and potato picking. An administrative centralization of reserves in the 1950s led to increased factionalism and population flight.

In the 1960s, many Micmac men began working in high-steel construction, on projects mainly in Boston. Women used vocational training to find work as nurses, teachers, and social workers. They also became increasingly active in band politics. Canadian Micmacs formed the Union of New Brunswick Indians and the Union of Nova Scotia Indians in 1969 to coordinate service programs and document land claims. They and other landless tribes formed the Association of Aroostook Indians in 1970 to try to raise their standard of living and fight discrimination. The tribe formed the Aroostook Micmac Council in 1982.

Religion Manitou, the ubiquitous creative spirit, was identified with the sun. Other deities in human form could be prevailed upon to assist mortals. All animals, but especially bears, were treated with respect, in part because it was believed that they could transform themselves into other species. The Micmacs’ rich mythology included Gluscap, the culture hero, as well as several types and levels of magical beings, including cannibalistic giants. Shamans were generally men and could be quite powerful. They cured, predicted the future, and advised hunters.

Government Small winter hunting groups, composed of households, came together in summer as bands, within seven defined districts. They also joined forces for war. Bands were identified in part through the use of distinctive symbols. There were three levels of chiefs, all with relatively little authority. Local hunting groups of at least 30 to 40 people were led by a hereditary headman (sagamore), usually an eldest son of an important family. These groups were loosely defined and of flexible membership. Chiefs of local groups provided dogs for the hunt, canoes, and food reserves. Sagamores also kept all game killed by unmarried men, and some of the game killed by married men.

There were also chiefs of the traditional seven districts. These leaders called district council meetings, entertained visiting chiefs, and participated in the grand council. At the top of the pyramid, at least from the nineteenth century on, there was also a grand chief or sagamore. In summer, this leader conferred grand councils to consider treaties as well as issues of war and peace.

Customs The general Micmac worldview valued moderation, equality, generosity, bravery, and respect for all living things. When the people gathered together from spring through fall, each group camped at a traditional place along the coast. There was a recognized social ranking in which commoners came below three levels of chiefs but above slaves, who were taken in war.

Children were welcomed and treated indulgently. A newborn’s first meal was bear or seal grease. Women resumed normal activities immediately after giving birth. They generally avoided new pregnancies for several years, until the child had been weaned. Children as well as the elderly were treated with respect and affection, although little or no effort was made to help ill or old people remain alive.

There were many occasions for feasting and dancing, especially as part of life-cycle events. The Micmac probably observed a woman’s puberty ceremony; boys were considered men when they had killed their first large game. There were elaborate menstrual taboos, including seclusion. Women’s tasks included gathering firewood, making clothing and bark containers, bringing game into camp, and setting up the wigwam. Older brothers and sisters generally avoided each other. Men used the sweat lodge for purification.

Marriages were generally arranged. A prospective husband, usually at least age 20, spent at least two years working for his future father-in-law as a hunter and general provider. After the probationary period,he provided game for a big wedding feast, including dancing (first marriages only). The birth of children formalized a marriage. Adultery was rare, although polygyny was practiced.

Longevity (life spans over 100 years) was not unusual before contact with Europeans. People gave their own funeral orations shortly before they died, if possible. Burial and a feast followed a three-day general mourning period. In some locations, corpses were wrapped in bark and buried with personal effects on an uninhabited island. There was also scaffold burial. Close relatives cut their hair and observed a yearlong mourning period.

Dwellings Micmacs built their inland winter camps near streams. Single extended families lived in conical wigwams of birch bark, skins or woven mats. Each had a central indoor fireplace. The inside was divided into several compartments for cooking, eating, sleeping, and other activities. Floors were covered with boughs, and fur-covered boughs served as beds. The people may have had rectangular, open, multifamily summer houses.

Diet In winter, small bands hunted game such as moose, bear, caribou, and porcupine. They also trapped smaller game such as beaver, otter, and rabbit and ate land and water birds (and their eggs). Moose were stalked with disguises and attracted with callers. Dogs helped in the hunt. Meat and fish were eaten fresh, roasted, broiled, boiled, or smoked. Pounded moose bones yielded a nutritious "butter."

People fished in spring and summer for eel, salmon, cod, herring, sturgeon, and smelt. They also collected shellfish and hunted seals and other marine animals. Salmon and fowl were sometimes speared at night with the light of birch-bark torches. The sea provided most of the summer diet.

They also gathered a number of wild berries, roots, and nuts. They occasionally ate dog, especially at funeral feasts, but they generally avoided snakes, amphibians, and skunks.

Key Technology Men made birch-bark moose calls and boxes. They also made double-edged moose-bone-blade spears and bows and stone-point arrows for hunting as well as snares and deadfalls for trapping. They fished with nets, bone hooks, weirs, and bone-tipped harpoons.

Meat was boiled with hot stones in hollowed wooden troughs. Women made reed and coiled spruce-root baskets, woven mats, and possibly pottery.

Trade Micmacs generally served as intermediaries between northern hunters and southern farmers.

Notable Arts Women decorated clothing and containers with dyed porcupine quillwork. Wigwams were sometimes carefully painted, especially with symbols distinctive to each band.

Transportation Men built 8- to 10-foot-long, seaworthy birch-bark and caribou-skin canoes. They made two types of square-toed snowshoes, one for powder and one for frozen surfaces. Women carried burdens using backpacks and tumplines.

Dress People dressed in skin robes fastened with one (men) or two (women) belts, moose-skin or deerskin leggings, and moccasins. Men also wore loincloths. Both sexes wore their hair long. People tattooed band symbols on their bodies.

War and Weapons Small population groups came together as bands for war. The people were allied with southern Algonquians as members of the Abenaki Confederacy. Their traditional enemies included the Beothuk, Labrador Eskimo, Maliseet (occasionally), Iroquois (especially Mohawk) around the St. Lawrence River, and New England Algonquians.

The Micmac adopted some Iroquois war customs, such as the torture of prisoners by women. Their weapons included bows, poisoned arrows, spears with moose-bone blades, and possibly stone tomahawks. There was some interband fighting (intraband disputes were generally resolved by individual fighting or wrestling). Captives were taken as slaves, tortured and killed, or, especially in the case of young women, adopted.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The Aroostook Band of Micmacs is governed by an elected board of directors. Headquarters for the tribal council is in Presque Isle,Maine. Band membership was slightly less than 500 in 1991.

The approximately 28 Canadian reserves include Pictou Landing, Eskasoni, and Shubenacadie in Nova Scotia and Burnt Church, Eel River Bar, Pabineau, Red Bank, Eel Ground, Indian Island, Bouctouche, Fort Folly, and Big Cove in New Brunswick. The three Micmac communities in Quebec are Listuguj (3,663.22 hectares; 2,621 people in 1994, of whom 1,641 live within the territory), Gesgapegiag (182.26 hectares; 936 people in 1994, of whom 432 live within the territory), and Gaspe (no area; 435 people in 1994).

Each is governed by a band council. Some are represented by captains of the Grand Council. The Grand Council, traditional government of the Micmac Nation, unites the six districts of Micmac territory (Quebec’s Gaspe Peninsula, northern and eastern New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island).

Economy Fishing, especially for salmon, remains important. Maine Micmacs operate a mail-order crafts cooperative. There have been some land claims victories in Canada, particularly a $35 million settlement to the Micmac of the Pictou Landing reserve.

Legal Status The Aroostook Band of Micmacs is a federally recognized tribal entity. Excluded from the giant 1980 Maine Indian land claim settlement, the tribe persuaded the federal government in 1991 to pass the Aroostook Band of Micmacs Settlement Act, which provided it with land and a tax fund as well as federal benefits. Newfoundland Indians organized in 1973 and were recognized under the Indian Act in 1984.

Daily Life Many Micmacs still speak the native language. Most are Catholics. Micmacs tend to be active in various pan-Indian organizations. There have been some gains in Canadian Micmacs’ quest to regain their hunting and fishing rights. Canadian Micmacs still face severe problems such as substance abuse, discrimination, and a high suicide rate. Roughly 40 percent of Canadian Micmacs speak their ancestral language.