Kiowa, "Principal People," is a derivation of Ka’i gwu, their self-designation.

Location The Kiowa migrated in the seventeenth century from the Gallatin-Madison Valleys in southwestern Montana to the Black Hills. By the early nineteenth century, their territory included southeast Colorado, extreme northeast New Mexico, southwest Kansas, northwest Oklahoma, and extreme north Texas.

Population In the late eighteenth century there were around 2,000 Kiowas. Roughly 10,000 people were enrolled Kiowas in the early 1990s.

Language Kiowa is considered a linguistic isolate that might be related to Tanoan, a Pueblo language, as well as Shoshonean.

Historical Information

History The Kiowa may have originated in Arizona or in the mountains of western Montana. They began drifting southeast from western Montana in the late seventeenth century, settling near the Crow. In the early eighteenth century, the Kiowa Apaches became cut off from their fellow Apacheans, at which time (if not a generation before) they joined the Kiowa for protection. Although they maintained a separate language and identity they functioned effectively as a Kiowa band.

Meanwhile, the Kiowa had acquired horses, probably through trade with upper Missouri tribes, and were living in the Black Hills as highly successful buffalo hunters, warriors, and horsemen. Individual Kiowas and Kiowa Apaches also lived in northern New Mexico, probably brought there originally by Comanches and others as prisoners or slaves. Later in the century, the Kiowa, still in the Black Hills, acted as trade intermediaries between Spanish (New Mexican) traders and the upper Missouri tribes.

The people suffered a smallpox epidemic in 1781, from which they gradually recovered. A large group of Kiowa and Kiowa Apache migrated south during that period, to be followed by the rest around the turn of the century. At that time, the Kiowa were pushed south to the Arkansas River area by Dakotas,

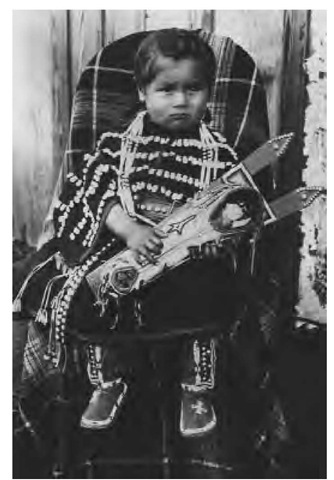

Kea-Boat, a member of the Kio was, holds a rattle and feather fan used in the Peyote ceremony.

Arapahos, and Cheyennes (southeastern Colorado), where they ran into the Comanche barrier. They were also drawn south by raiding opportunities provided by Spanish and Pueblo settlements in New Mexico and Mexico. In the early nineteenth century they ranged between New Mexico and the upper Missouri River area.

In 1814 they concluded a treaty with the Dakota defining the boundary between the two groups. Making peace also with the Comanche, these two groups raided for horses, guns, and food as far south as Durango, Mexico. They were known as fierce, effective, and wide-ranging raiders, fighting other Indian groups as well as Spanish, Mexicans, and Anglos. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Kiowa spent more time south of the Arkansas than north of it. In the 1830s they made peace with longtime Cheyenne, Osage, and Arapaho enemies.

In the early 1860s, the Kiowa strongly resisted non-native intruders, land thieves, and immigrants. In 1865 they agreed to a reservation south of the Arkansas River. In the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty, they ceded tribal lands and, in exchange for a shared reservation in the Indian Territory, agreed to hunt buffalo only south of the Arkansas and withdrew opposition to a railroad. After the U.S. massacre of Cheyennes called the Battle of the Washita (December 1868), Kiowas and others were ordered to Fort Cobb, Oklahoma. Kiowas, citing provisions in the Medicine Lodge Treaty that allowed then to continue to live and hunt south of the Arkansas, refused. During a peace meeting in 1869, the Kiowa negotiators, Satanta (White Bear) and Lone Wolf, were taken prisoner and placed under a death sentence unless the Kiowa surrendered, which they did.

Two thousand Kio was and 2,500 Comanches were placed on a reservation at Fort Sill, Indian Territory (Oklahoma). The United States encouraged them to farm, but the Kiowa were not farmers. With starvation looming, the United States permitted them to hunt buffalo. In 1870 and 1871, the Kiowa went on a buffalo hunt and continued their old raiding practices to the south. Some argued for remaining free while others spoke for cooperating with the United States. In 1871, soldiers arrested Kiowa leaders Satanta, Satank, and Big Tree for murders committed during the raids. Satank was killed on the way to his trial in Texas. The other two were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. During a meeting in Washington the following year, Lone Wolf won their release as a condition for keeping the Kiowas peaceful.

In 1873, a party of Kiowas and Comanches raided in Mexico for horses. The following year, a group of Indians including Kiowas fought a losing battle against whites at Adobe Walls. By this time, most of the great buffalo herds, almost four million buffalo, had been killed by non-Indians. That summer, a large group of Kiowas and Comanches left Fort Sill for the last great buffalo range at Palo Duro Canyon, Texas, to live as traditional Indians once again. In the fall, U.S. soldiers hunted them down and killed 1,000 of their horses. Fleeing, scattered groups of Indians were hunted down in turn.

The last of these people surrendered in February 1875. They were kept in corrals. Satanta was returned to prison in Texas, and 26 others were exiled to Florida. Kicking Bird died mysteriously two days after the exiles he selected had departed, possibly poisoned by those who resented his friendship with the whites. Within a few years, the great leaders were all gone, and the power of the Kiowa was broken.

The late 1870s saw a major measles epidemic and the end of the Plains buffalo; more epidemics followed in 1895 and 1902. Many Kiowas took up the Ghost Dance in the late 1880s and early 1890s. In 1894, Kiowas offered to share their reservation with their old Apache enemies who were exiles in Florida; Geronimo and other Chiricahua Apaches lived out their lives there.

Almost 450,000 acres of the reservation were allotted to individuals in 1901, with the remaining more than two million acres then sold and opened for settlement to non-natives. Kiowas were among the group of Indians who organized the Native American Church in 1918, having adopted ritual peyote use around 1885. Thanks to the legacy of Kicking Bird and others, Kiowas in the twentieth century have concentrated on education, sending their children to boarding schools (including Riverside, still active in the 1990s) and several nearby mission schools.

Religion Kiowas gained religious status through shield society membership and/or guardianship of sacred tribal items, such as the Ten Grandmother Bundles. According to legend, the bundles originated with Sun Boy, the culture hero. With their associated ceremonies, they were a focus of Kiowa religious practice.

Kiowas adopted the Sun Dance in the eighteenth century, although they did not incorporate elements of self-mutilation into the ceremony. Young men also fasted to produce guardian spirit visions.

Government There were traditionally between 10 and 27 autonomous bands, including the Kiowa Apache, each with its own peace and war chiefs. Occasionally, especially later in their history, a tribal chief presided over all the bands.

Customs Beginning in the nineteenth century the Kiowa adopted a social system wherein rank was based especially on military exploits and also on wealth and religious power. There were four named categories of social rank. The highest was held by those who had attained war honors and were skilled horsemen, generous, and wealthy. Then came those men who met all the preceding criteria except war honors. The third group included people without property. At the bottom were men with neither property nor skills. War captives remained outside this ranking system.

Generosity was valued, and wealthy men regularly helped the less fortunate, but in general wealth remained in the family through inheritance. Sons from wealthy families could begin their military training earlier and thus, through military success, gain even more wealth. There were numerous specialized men’s and women’s societies.

Bands lived apart in winter but came together in summer to celebrate the Sun Dance. Corpses were buried or left in a tipi on a hill. Former possessions were given away. Mourners cut their hair and gashed themselves, even occasionally cutting off fingers. A mourning family lived apart during the appropriate period of time.

Dwellings Women built and owned skin tipis.

Diet Buffalo supplied most of the food, shelter, and clothing for Kiowas on the Plains. Buffalo hunts were highly organized and ritualized affairs. After the hunt, women cut the meat into strips to dry. Later, they mixed it with dried chokecherries and fat to make pemmican, which remained edible in skin bags for up to a year or more.

Men also hunted other large and small game. They did not eat bear or, usually, fish. Women gathered a variety of wild potatoes and other vegetables, fruits, nuts, and berries. Kiowas ate dried, pounded acorns and also made them into a drink. Cornmeal and dried fruit were acquired by trade.

Key Technology Kiowas made pictographs on buffalo skins to record events of tribal history. They used the buffalo and other animals to provide the usual material items such as parfleches and other containers. Points for bird arrows came from prickly pear thorns. The cradle board was a bead-covered skin case attached to a V-shaped frame. Women made shallow coiled basketry gambling trays.

Trade During the eighteenth century, Kiowas traded extensively with the upper Missouri tribes (Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras). They exchanged meat, buffalo hides, and salt with Pueblo Indians for cornmeal and dried fruit. During the nineteenth century they traded Comanche horses to the Osage and other tribes.

Notable Arts Calendric skins and beadwork were two Kiowa artistic traditions.

Transportation The people acquired horses by 1730.

Dress Women dressed buffalo, elk, and deer hides to make robes, moccasins, leggings, shirts, breechclouts, skirts, and blouses.

War and Weapons The highest status for men was achieved through warfare. Counting coup and leading a successful raid or fight were the most prestigious military activities. Raiding groups were usually drawn from kin groups, whereas revenge war parties were larger (up to 200 men) and formally organized following a Sun Dance. War honors were recounted following the fight and at any future event at which the recipients spoke formally.

The numerous military societies included the Principal Dogs (or Ten Bravest), a group of ten extremely brave and tested fighters. During battle, one of these warriors would drive a spear through his sash into the ground and fight from that spot, not moving until another Principal Dog removed the spear. Satank (Sitting Bear) was the leader of the Principal Dogs during the last phase of Kiowa resistance.

Kiowas beginning a raid sometimes appealed to a group of women for their prayers, feasting them upon their return. The tribe was allied with the Crow in the late seventeenth century, and the Comanche beginning around 1790. Enemies in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century included the Dakota, Cheyenne, and Osage.

The beadwork in this young Kiowa girl’s finery (1921) exemplifies a long-standing Kiowa artistic tradition.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The Kiowa organized a tribal council in 1968. A 1970 constitution and bylaws divided power between the Kiowa Indian Council (all tribal members) and the eight-member elected Kiowa Business Committee. Tribal headquarters are located in Carnegie, Oklahoma.

The Kiowa land base is 208,396 acres in Caddo, Kiowa, Comanche, Tillman and Cotton Counties, Oklahoma. This land was first designated to them in 1867. Just over 7,000 acres are tribally owned.

Economy Important sources of income include farming, raising livestock, and leasing oil rights.

Legal Status The Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma is a federally recognized tribal entity.

Daily Life Many prominent Kiowa artists have played an important part in the twentieth-century revival of Indian arts, beginning in 1927 with the introduction of the "Kiowa Five"—Spencer Asah, Jack Hokeah, Stephan Mopope, Monroe Tsatoke, and James Auchiah. In addition to painting, contemporary Kiowa artists are involved in media such as buckskin, beads, and silver. N. Scott Momaday, a distinguished novelist and professor, won the 1969 Pulitzer for his novel House Made of Dawn.

Most Kiowas are Christians, predominantly Baptists and Methodists. Many also belong to the Native American Church. As of the early 1990s, fewer than 400 spoke the native language, and almost all of these were over 50. Still, many elements of traditional culture have been preserved. Even the children’s Rabbit Society, with its special songs and dances, endures. The tribe publishes the Kiowa Indian News.