Iglulik![]() , a name derived (with their main settlement, Igloolik) from the custom of living in snow houses, or igloos. See also Inuit, Baffinland.

, a name derived (with their main settlement, Igloolik) from the custom of living in snow houses, or igloos. See also Inuit, Baffinland.

Location Traditional Iglulik territory is north of Hudson Bay, including northern Baffin Island, the Melville Peninsula, Southhampton Island, and part of Roes Welcome Sound. It lies within the central Arctic, or Kitikmeot.

Population Estimated at 500 in the early nineteenth century, the 1990 Iglulik population was about 2,400.

Language Igluliks speak a dialect of Inuit-Inupiaq (Inuktitut), a member of the Eskaleut language family.

Historical Information

History The people encountered Scottish whalers early in the nineteenth century. Eventually, Scottish celebrations came to supplant traditional ones in part. By the time American whalers arrived in the 1860s, the Iglulik had acquired whaleboats, guns, iron items, tea, and tobacco. Later in the century, the people became involved with fox trapping and musk ox hunting. They also intermarried with non-natives and acquired high rates of alcoholism and venereal disease.

Regular contact with other Inuit, such as the Netsilik, was established at local trading posts and missions. These arrived in the early twentieth century, as did a permanent presence of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Improved medical care followed these inroads of non-native influence.

The far north took on strategic importance during the Cold War, about the same time that vast mineral reserves became known and technologically possible to exploit. These developments encouraged population movements. Also, as non-natives increased their influence, such aspects of traditional culture as shamanism, wife exchange, and murders began to disappear. In 1954 the federal Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources officially encouraged Inuit to abandon nomadic life. It built housing developments, schools, and clinics. Local political decisions were made by a community council subject to non-native approval and review.

The snowmobile, introduced in early 1960s, increased the potential trapping and hunting area and diminished the need for meat (fewer dogs to feed). Such employment as Inuit could obtain was generally unskilled and menial. With radical diet changes (including flour and sugar), the adoption of a sedentary life, and the appearance of drugs and alcohol, the people’s health declined markedly.

Religion Religious belief and practice were based on the need to appease spirit entities found in nature. Hunting, and specifically the land-sea dichotomy, was the focus of most rituals and taboos, such as that prohibiting sewing caribou skin clothing in certain seasons. The people also recognized generative spirits, conceived of as female and identified with natural forces and cycles. A rich body of legends was related during the long, dark nights.

Male and female shamans (angakok) provided religious leadership by virtue of their connection with guardian spirits. They could also control the weather, improve conditions for hunting, cure disease, and divine the future. Illness was due to soul loss and/or violation of taboos and/or the anger of the dead. Curing methods included interrogation about taboo adherence, trancelike communication with spirit helpers, and performance.

Government There was no real political organization; nuclear families came together in the fall to form local groups, or settlements, that in turn were grouped into three divisions—Iglulingmiut,Aivilingmiut, and Tununermiut—associated with geographical areas (-miuts). Local group leaders were usually older men, with little formal authority and no power. Leaders generally embodied Inuit values, such as generosity, and were also good hunters.

Customs Sharing was paramount in Inuit society. Descent was bilateral. People came together in larger group gatherings in late autumn; that was a time to sew and mend clothing and renew kinship ties. Spring was also a time for visiting and travel.

People married simply by announcing their intentions, although infants were regularly betrothed. Prospective husbands often served their future in-laws for a period of time. Men might have more than one wife, but most had only one. Divorce was easy to obtain. The people also recognized many other types of formal and informal partnerships and relationships. Some of these included wife exchanges.

A woman gave birth in a special shelter and lived in another special shelter, in which she observed various taboos, for some time after the birth. Because infant mortality was high, infanticide was rare, and usually practiced against females. Babies were generally named after a deceased relative. Children were highly valued and loved, especially males. They were generally given a high degree of freedom. After puberty, siblings of the opposite sex acted with reserve toward each other. This reached an extreme in the case of brothers- and sisters-in-law.

The sick or aged were sometimes abandoned, especially in times of scarcity, or the aged might commit suicide. Corpses lay in state for three days, after which they were wrapped in skins, taken out through the rear of the house, and buried in the snow. The tools of the deceased were left with him or her. No activities, including hunting, were permitted for six days following a death.

Feuds, with blood vendettas, were a regular feature of traditional life. Tensions were relieved through games; duels of drums and songs, in which the competing people tried to outdo each other in parody and song; some joking relationships; and athletic contests. Outdoor games included ball, hide-and-seek, and contests. There were many indoor games as well. These activities also took place on regular social occasions, such as visits. Ostracism and even death were reserved for the most serious cases of socially inappropriate behavior.

Dwellings The people lived in domed snow houses for part of the winter. They entered through an above-ground tunnel that trapped the warm air inside. Snow houses featured porches for storage and sometimes had more than one room. Ice or gut skin served as windows. Some groups lined the snow house with sealskins. Snow houses were often joined together at porches to form multifamily dwellings. People slept on raised packed snow platforms on caribou hide bedding. Some larger snow houses were built for social and ceremonial purposes. People generally lived in sealskin tents in summer. In spring and fall some groups used stone houses reinforced with whalebone and sod and roofed with skins.

Diet The Iglulik were nomadic hunters. The most important game animals were seals, whales, walrus, and narwhal. Men hunted seals at their breathing holes in winter and from boats in summer, as they did whales and walrus. In summer, the people traveled inland to hunt caribou, musk ox, and birds and to fish, especially for salmon and trout. Other foods included some berries and birds and their eggs. Meat, which might not be very fresh, was cooked in soapstone pots over soapstone blubber lamps or eaten raw or frozen. In summer, people burned oil-soaked bones for cooking fuel.

Key Technology Men used bone knives to cut blocks for snow houses. Other tools and equipment included harpoons, spears, snares, lances, bow and arrow, and bolas. They caught fox and wolf in stone or ice traps. Bows were made of spruce with sealskin and sinew backing. Some were also made of musk ox horn or antler. Many tools were made from caribou antlers as well as stone, bone, and driftwood. Blades were made of bone or copper. Fires were started with flint and pyrite or a wooden drill.

Fishing equipment included hooks, wooden or stone weirs and traps, and a variety of spears and harpoons. The people carved soapstone cooking pots and seal-oil lamps as well as wooden utensils, trays, dishes, spoons, and other objects. Women sewed with bone needles and sinew thread and used curved knives and scrapers to prepare skins.

Trade Material goods were exchanged with nearby neighbors, both Iglulik and non-Iglulik, mostly in summer.

Notable Arts The people carved wooden and ivory objects and made finely tanned skin clothing decorated with bands of color.

Transportation Men hunted in one- or two-person sealskin kayaks. Occasionally, several might be lashed together to form a raft. Umiaks were larger, skin-covered open boats. Dogs pulled wooden sleds, the whalebone or wood runners of which were covered with ice. Dogs also carried small packs during seasonal travel.

Dress Women sewed most clothing from caribou skins, although sealskins were commonly used on boots. Apparel included men’s long, gut sealing coats and light swallowtail ceremonial coats. The people wore a double skin suit in winter and only the inner layer in summer. Most men’s parkas had a long flap in the back; the woman’s had two long, narrow flaps. Women’s clothing featured large shoulders and hoods as well as one-piece, attached leggings and boots. They wore high caribou skin and sealskin boots containing square pouches. Men wore small loon-beak dancing caps with weasel-skin tassels. They sometimes shaved their foreheads. Both sexes wore tattoos and ivory or bone snow goggles.

War and Weapons There was some intragroup fighting and some fighting as well with the Netsilik. Hunting equipment generally doubled as weapons of war.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations Contemporary communities include: Ausuittuq (Grise Ford), Iglulik (Igloolik), Ikpiarjuk/Tununirusiq (Arctic Bay), Iqaluit, Mittimatalik/Tununiq (Pond Inlet), Qausuittuq (Resolute Bay), and Sanirajuk (Hall Beach). Government is by locally elected community council.

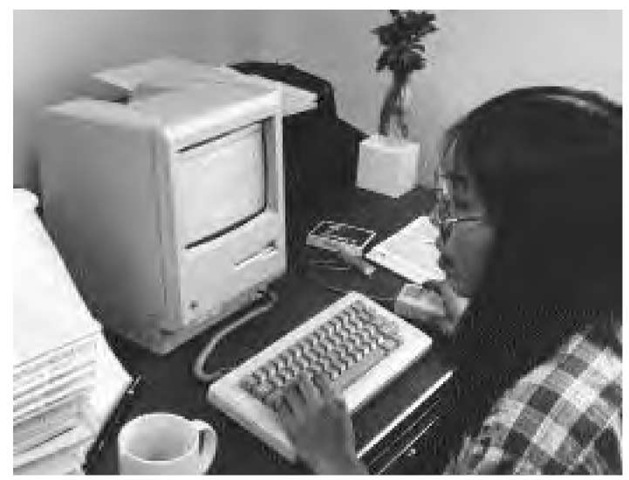

Translator Annie Iola, working with a specially designed word processor keyboard, translates English-language copy into Inuktitut at the Nunatsiaq News, a weekly publication in the northern Canadian town of Igaluit (1987).

Economy There is some employment in oil fields and mines. Government assistance is an important source of income for many Iglulik. The Iglulik economy today is mainly money based. Unemployment was officially pegged at 30 percent in 1994.

Native-owned and -operated cooperatives have been an important part of the Inuit economy for some time. Activities range from arts and crafts to retail to commercial fishing to construction. Woodcarving is particularly important among the Iglulik.

Legal Status Inuit are considered "nonstatus" native people. Most Inuit communities are incorporated as hamlets and are officially recognized. Baffin Island is slated to become a part of the new territory of Nunavut.

Daily Life The Baffin Regional Association was formed to press for political rights. In 1993, the Tungavik Federation of Nunavut (TFN), an outgrowth of the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (ITC), signed an agreement with Canada providing for the establishment in 1999 of a new, mostly Inuit, territory on roughly 36,000 square kilometers of land, including Baffin Island.

The people never abandoned their land, which is still central to their identity. Traditional and modern coexist, sometimes uneasily, for many Inuit. Although people use television (there is even radio and television programming in Inuktitut), snowmobiles, and manufactured items, women also carry babies in the traditional hooded parkas, chew caribou skin to make it soft, and use the semilunar knives to cut seal meat. Full-time doctors are rare in the communities. Housing is often of poor quality. Most people are Christians. Culturally, although many stabilizing patterns of traditional culture have been destroyed, many remain. Many people live as part of extended families. Adoption is widely practiced. Decisions are often taken by consensus. However, with access to the world at large, social problems, including substance abuse and suicide among the young, have increased. Fewer than half of the people finish high school.

Politically, community councils have gained considerably more autonomy over the past decade or two. There is also a significant Inuit presence in the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly and some presence at the federal level as well. The disastrous effects of government-run schools have been mitigated to some degree by local control of education, including more culturally relevant curricula in schools. Many people still speak Inuktitut, which is also taught in most schools, especially in the earlier grades. Children attend school in their community through grade nine; the high school is in Frobisher Bay. Adult education is also available.