Hopi![]() from Hopituh Shi-nu-mu, "Peaceful People." They were formerly called the Moki (or Moqui) Indians, a name probably taken from a Zuni epithet.

from Hopituh Shi-nu-mu, "Peaceful People." They were formerly called the Moki (or Moqui) Indians, a name probably taken from a Zuni epithet.

Location The Hopi are the westernmost of the Pueblo peoples. First, Second, and Third Mesas are all part of Black Mesa, located on the Colorado Plateau between the Colorado River and the Rio Grande, in northeast Arizona. Of the several Hopi villages, all but Old Oraibi are of relatively recent construction.

Population Hopi population was perhaps 2,800 in the late seventeenth century. It was roughly 7,000 in 1990.

Language Hopi, a Shoshonean language, is a member of the Uto-Aztecan language family.

Historical Information

History The Hopi are probably descended from the prehistoric Anasazi culture. Ancestors of the Hopi have been in roughly the same location for at least 10,000 years. During the fourteenth century, Hopi became one of three centers of Pueblo culture, along with Zuni/Acoma and the Rio Grande pueblos.

Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, three traits in particular distinguished the Hopi culture: a highly specialized agriculture, including selective breeding and various forms of irrigation; a pronounced artistic impulse, as seen in mural and pottery painting; and the mining and use of coal (after which the Hopi returned to using wood for fuel and sheep dung for firing pottery).

The Hopi first met non-native Americans when members of Coronado’s party came into their country in 1540. The first missionary arrived in 1629, at Awatovi. Although the Spanish did not colonize Hopi, they did make the Indians swear allegiance to the Spanish Crown and attempted to undermine their religious beliefs. For this reason, the Hopis joined the Pueblo rebellion of 1680. They destroyed all local missions and established new pueblos at the top of Black Mesa that were easier to defend. The Spanish reconquest of 1692 did not reach Hopi land, and the Hopis welcomed refugees from other pueblos who sought to live free of Spanish influence. In 1700, the Hopis destroyed Awatovi, the only village with an active mission, and remained free of Christianity for almost 200 years thereafter.

During the nineteenth century the Hopi endured an increase in Navajo raiding. Later in the century they again encountered non-natives, this time permanently. The U.S. government established a Hopi reservation in 1882, and the railroad began bringing in trading posts, tourists, missionaries, and scholars. The new visitors in turn brought disease epidemics that reduced the Hopi population dramatically.

Like many tribes, the Hopi struggled to deal with the upheaval brought about by these new circumstances. Following the Dawes Act (1887), surveyors came in preparation for parceling the land into individual allotments; the Hopis met them with armed resistance. Although there was no fighting, Hopi leaders were imprisoned. They were imprisoned as well for their general refusal to send their children to the new schools, which were known for brutal discipline and policies geared toward cultural genocide. Hopi children were kidnapped and sent to the schools anyway.

Factionalism also took a toll on Hopi life. Ceremonial societies split between "friendly" and "hostile" factions. This development led in 1906 to the division of Oraibi, which had been continuously occupied since at least 1100, into five villages. Contact with the outside world increased significantly after the two world wars. By the 1930s, the Hopi economy and traditional ceremonial life were in shambles (yet the latter remained more intact than perhaps that of any other U.S. tribe). Most people who could find work worked for wages or the tourist trade. For the first time, alcoholism became a problem.

In 1943, a U.S. decision to divide the Hopi and Navajo Reservations into grazing districts resulted in the loss of most Hopi land. This sparked a major disagreement between the tribes and the government that continues to this day. Following World War II, the "hostile" traditionalists emerged as the caretakers of land, resisting cold war policies such as mineral development and nuclear testing and mining. The official ("friendly") tribal council, however, instituted policies that favored exploitation of the land, notably permitting Peabody Coal to strip-mine Black Mesa, beginning in 1970.

Religion According to legend, the Hopi agreed to act as caretakers of this Fourth World in exchange for permission to live here. Over centuries of a stable existence based on farming, they evolved an extremely rich ceremonial life. The Hopi Way, whose purpose is to maintain a balance between nature and people in every aspect of life, is ensured by the celebration of their ceremonies.

The Hopi recognize two major ceremonial cycles, masked (January or February until July) and unmasked, which are determined by the position of the sun and the lunar calendar. The purpose of most ceremonies is to bring rain. As the symbol of life and well-being, corn, a staple crop, is the focus of many ceremonies. All great ceremonies last nine days, including a preliminary day. Each ceremony is controlled by a clan or several clans. Central to Hopi ceremonialism is the kiva, or underground chamber, which is seen as a doorway to the cave world from whence their ancestors originally came.

Katsinas are guardian spirits, or intermediaries between the creator and the people. They are said to dwell at the San Francisco peaks and at other holy places. Every year at the winter solstice, they travel to inhabit people’s bodies and remain until after the summer solstice. Re-created in dolls and masks, they deliver the blessings of life and teach people the proper way to live. Katsina societies are associated with clan ancestors and with rain gods. All Hopis are initiated into katsina societies, although only men play an active part in them.

Perhaps the most important ceremony of the year is Soyal, or the winter solstice, which celebrates the Hopi worldview and recounts their legends. Another important ceremony is Niman, the harvest festival. The August Snake Dance has become a well-known Hopi ceremony.

Like other Pueblo peoples, the Hopi recognize a dual division of time and space between the upper world of the living and the lower world of the dead. Prayer may be seen as a mediation between the upper and lower, or human and supernatural, worlds. These worlds coexist at the same time and may be seen in oppositions such as summer and winter, day and night, life and death. In all aspects of Hopi ritual, ideas of space, time, color, and number are all interrelated in such a way as to provide order to the Hopi world.

Government Traditionally, the Hopi favored a weak government coupled with a strong matrilineal, matrilocal clan system. They were not a tribe in the usual sense of the word but were characterized by an elaborate social structure, each village having its own organization and each individual his or her own place in the community. The "tribe" was "invented" in 1936, when the non-native Oliver La Farge wrote their constitution. Although a tribal council exists, many people’s allegiance remains with the village kikmongwi (cacique). A kikmongwi is appointed for life and rules in matters of traditional religion. Major villages include Walpi (First Mesa), Shungopavi (Second Mesa), and Oraibi (Third Mesa).

Customs Hopi children learn their traditions through katsina dolls, including scare-katsinas, as well as social pressure, along with an abundance of love and attention. This approach tends to encourage friendliness and sharing in Hopi children. In general, women owned (and built) the houses and other material resources while men farmed and hunted away from the village. Special societies included katsina and other men’s and women’s organizations concerned with curing, clowning, weather control, and war.

Following a death, the deceased’s hair was washed with yucca suds and decorated with prayer feathers. The face was covered with a mask of raw cotton, to evoke the clouds. He or she was then wrapped in a blanket and buried in a sitting position, with food and water. Cornmeal and prayer sticks were also placed in the grave, with a stick for a spirit ladder.

Dwellings Distinctive one- or two-floor pueblo housing featured sandstone and adobe walls and roof beams of pine and juniper, gathered from afar. The dwellings were entered via ladders through openings in the roofs and were arranged around a central plaza. This architectural arrangement reflects and reinforces cosmological ideas concerning emergence from an underworld through successive world levels.

Diet Hopis have been expert dry farmers for centuries, growing corn, beans, squash, cotton, and tobacco on floodplains and sand dunes or, with the use of irrigation, near springs. The Spanish brought crops such as wheat, chilies, peaches, melons, and other fruit. Men were the farmers and hunters of game such as deer, antelope, elk, and rabbits. The Hopi also kept domesticated turkeys. Women gathered wild food and herbs, such as pine nuts, prickly pear, yucca, berries, currants, nuts, and seeds. Crops were dried and stored against drought and famine.

Hopi children learn their traditions through katsina dolls (pictured here), as well as social pressure, along with an abundance of love and attention. These dolls, carved out of cottonwood, represent the various masked katsinas.

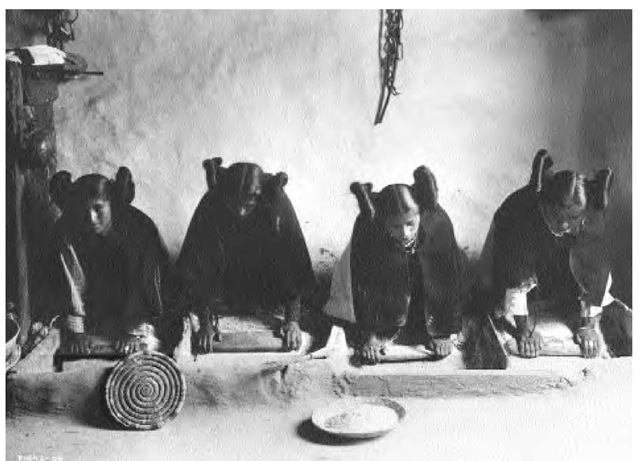

Key Technology Farming technology included digging sticks (later the horse and plow), small rock or brush-and-dirt dams and sage windbreaks, and an accurate calendar on which each year’s planting time was based. Grinding tools were made of stone. Men wove clothing and women made pottery, which was used for many purposes. Men also hunted with the bow and arrow and used snares and nets to trap animals.

Trade The Hopi obtained gems, such as turquoise, from Zuni and Pueblo tribes. Shell came from the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. They also traded for sheep and wool from the Navajo, buckskins from the Havasupai, and mescal from various tribes.

Notable Arts Fine arts included pottery decorated with designs based on ancient geometric patterns, made by women. Men spun and wove cotton into costumes and clothing, for domestic use and for trade. Designs were generally asymmetrical but balanced between objects and color to render an idea of harmony. Other fine arts included silversmithing, introduced by the Navajo in 1890; weaving baskets and blankets; painting; and creating katsina dolls.

Transportation Horses arrived with the Spanish in the sixteenth century.

Dress Clothing was usually made of cotton and included long dresses for women and loincloths for men. Both wore leather moccasins and rabbit-skin robes as well as blankets and fur capes for warmth. Unmarried women wore their hair in the shape of a squash blossom; braids were preferred after marriage.

War and Weapons The annual war society ceremony is now obsolete.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The Hopi Reservation was established in 1882. Consisting originally of almost 2.5 million acres, the total land base stood at just over 1.5 million acres in 1995. Thirteen Hopi villages now stand on three mesas. A tribal council was created in 1936, although only two of the villages were represented in 1992.

Hopis are also members of the Colorado River Indian Tribes Reservation (see Mojave).

Economy As they have for centuries, Hopis continue to farm for their food. They also raise sheep and cattle. Crafts for the tourist trade— especially silver jewelry, katsina dolls, and pottery—bring in some money. Seventy percent of the tribe’s operating budget comes from coal leases, but mineral leases remain exploitative, and their effects include strip mining, radiation contamination, and depletion of precious water resources. The tribal council has also invested in factories and in a cultural center/motel/museum complex.

These unmarried Hopi women wear their hair in the shape of a squash blossom (1912); braids were preferred after marriage.

Legal Status The Hopi are a federally recognized tribal entity, as are the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT), where some Hopis settled after World War II. The Hopi Reservation was carved in 1882 from traditional Hopi lands plus three villages of Navajos living on Hopi lands (settlers and refugees from U.S. Indian wars).

A major dispute has emerged within the tribe and among the Hopi tribal council, the Navajos, and the U.S. government over the lands around the part of the reservation known as Big Mountain. Technically the land belongs to the Hopis, but it has been homesteaded since the mid-eighteenth century by Navajos because, in their view, the Hopis were just "ignoring" it. The Hopi council wants the land for mineral exploitation. Hopi traditionalists want the Navajos to remain, out of solidarity, friendship with their old enemies, and their inclination to share. They would prefer that the land remain free of mineral exploitation.

These Hopi women are shown building adobe houses. Distinctive one- or two-floor pueblo housing featured sandstone and adobe walls and roof beams of pine and juniper, gathered from afar. The dwellings were entered via ladders through openings in the roofs and were arranged around a central plaza.

In 1986, the United States recognized the squatters’ rights by proclaiming 1.8 million acres of "joint use area": Each tribe got half, and those on the "other" side were to move. In effect, the Hopis lost half of their original reservation to the Navajo. More than 100 Hopis moved, but many Navajos remained. This conflict remains ongoing, with the Hopis still trying to hold onto their land. Many Indians believe that coal company profits are at the root of the dispute and forced relocations.

Daily Life The Hopi way continues; they are among the most traditional of all Indians in the United States. Hopis maintain a strong sense of the continuity of life and time. The split between "progressive" and "traditional" factions continues. Hopi High School, between Second and Third Mesas, opened in 1986 with an entirely local board. The school emphasizes Hopi culture and a new written language as well as computers and contemporary American curricula. The first dictionary of written Hopi is in preparation. The Hopi are making progress in solving not only the land dispute with the Navajo but also a host of social problems, including substance abuse and suicide.

Most Hopis live in the traditional pueblos, many of which now have glass windows. Perhaps 1,500 Hopis live and work off the reservation, although many return for ceremonies. Especially in some of the modern villages, houses contain plumbing and electricity and are constructed of cement blocks without benefit of a central plaza.