Havasupai![]() is a name meaning "People of the Blue-Green Water." With the Hualapai, from whom they may be descended, they are also called the Pai (Pa’a) Indians ("the People"; Hualapai are Western Pai, and Havasupai are Eastern Pai). With the Hualapai and the Yavapai, the Havasupai are also Upland Yumans, in contrast to River Yumans such as the Mojave and Quechan.

is a name meaning "People of the Blue-Green Water." With the Hualapai, from whom they may be descended, they are also called the Pai (Pa’a) Indians ("the People"; Hualapai are Western Pai, and Havasupai are Eastern Pai). With the Hualapai and the Yavapai, the Havasupai are also Upland Yumans, in contrast to River Yumans such as the Mojave and Quechan.

Location Since approximately 1100, the Havasupai have lived at Cataract Canyon in the Grand Canyon as well as on the nearby upland plateaus.

Population Of roughly 2,000 Pai, perhaps 250 Havasupai Indians lived at Cataract Canyon in the seventeenth century. Approximately 400 lived there in 1990.

Language The Havasupai spoke Upland Yuman, a member of the Hokan-Siouan language family.

Historical Information

History The Havasupai probably descended from the prehistoric Cohoninas, a branch of the Hakataya culture. Thirteen bands of Pai originally hunted, farmed, and gathered in northwest Arizona along the Colorado River. By historic times, the Pai were divided into three subtribes: the Middle Mountain People; the Plateau People (including the Blue Water People, also called Cataract Canyon Band, who were ancestors of the Havasupai); and the Yavapai Fighters.

The Blue Water People were comfortable in an extreme range of elevations. They gathered desert plants from along the Colorado River at 1,800 feet and hunted on the upper slopes of the San Francisco peaks, their center of the world, at 12,000 feet. With the possible exception of Francisco Garces, in 1776, few if any Spanish or other outsiders disturbed them into the 1800s. Spanish influences did reach them, however, primarily in the form of horses, cloth, and fruit trees through trading partners such as the Hopi.

In the early 1800s, a trail was forged from the Rio Grande to California that led directly through Pai country. By around 1850, with invasions and treaty violations increasing, the Pai occasionally reacted with violence. When mines opened in their territory in 1863, they perceived the threat and readied for war. Unfortunately for them, the Hualapai War (1865-1869) came just as the Civil War ended. After their military defeat by the United States, some Pai served as army scouts against their old enemies, the Yavapai and the Tonto Apache.

Although the Hualapai were to suffer deportation, the United States paid little attention to the Havasupai, who returned to their isolated homes. At this point the two tribes became increasingly distinct. Despite their remote location, Anglo encroachment eventually affected even the Havasupai, and an 1880 executive order established their reservation along Havasu Creek. The final designation in 1882 included just 518 acres within the canyon; the Havasupai also lost their traditional upland hunting and gathering grounds (some people continued to use the plateau in winter but were forced off in 1934, when the National Park Service destroyed their homes).

The Havasupai intensified farming on their little remaining land and began a wide-scale cultivation of peaches. In 1912 they purchased cattle. Severe epidemics in the early twentieth century reduced their population to just over 100. At the same time the Bureau of Indian Affairs, initially slow to move into the canyon, proceeded with a program of rapid acculturation. By the 1930s, Havasupai economic independence had given way to a reliance on limited wage labor. Traditional political power declined as well, despite the creation in 1939 of a tribal council.

Feeling confined in the canyon, the Havasupai stepped up their fight for permanent grazing rights on the plateau. The 1950s were a grim time for the people, with no employment and little tourism. Conflict over land led to deep familial divisions, which in turn resulted in serious cultural loss. Food prices at the local store were half again as high as those in neighboring towns. In the 1960s, however, an infusion of federal funds provided employment in tribal programs as well as modern utilities. Still, croplands continued to shrink, as more and more land was devoted to the upkeep of pack animals for the tourists, the tribe’s limited but main source of income. In 1975, after an intensive lobbying effort, the government restored 185,000 acres of land to the Havasupai.

Religion The Havasupai performed at least three traditional ceremonies a year, the largest coming in the fall at harvest time and including music, dancing, and speechmaking. They often invited Hopi, Hualapai, and Navajo neighbors to share in these celebrations. One important ceremony was cremation (burial from the late nineteenth century) and mourning of the dead, who were greatly feared. Although the Hopi influenced the Havasupai in many ways, such as the use of masked dancers, the rich Hopi ceremonialism did not generally become part of Havasupai life. Curing was accomplished by means of shamans, who acquired their power from dreams. The Havasupai accepted the Ghost Dance in 1891.

Government Formal authority was located in chiefs, hereditary in theory only, of ten local groups. Their only real power was to advise and persuade. The Havasupai held few councils; most issues were dealt with by men informally in the sweat lodge.

Customs The Havasupai were individualists rather than band or tribe oriented. The family was the main unit of social organization. In place of a formal marriage ceremony, a man simply took up residence with a woman’s family. The couple moved into their own home after they had a child. Women owned no property. Babies stayed mainly on basket cradle boards until they were old enough to walk. With some exceptions, work was roughly divided by gender.

Leisure time was spent in sweat lodges or playing games, including (after 1600 or so) horse racing. The Havasupai often sheltered Hopis in times of drought. Both sexes painted and tattooed their faces. Only girls went through a formal puberty ritual.

Dwellings In winter and summer, dwellings consisted of domed or conical wikiups of thatch and dirt over a pole frame. People also lived in rock shelters. Small domed lodges were used as sweat houses and clubhouses.

Diet In Cataract Canyon the people grew corn, beans, squash, sunflowers, and tobacco. During the winter they lived on the surrounding plateau and ate game such as mountain lion and other cats, deer, antelope, mountain sheep, fowl, and rabbits, which were killed in communal hunting drives. Wild foods included pinon nuts, cactus and yucca fruits, agave hearts, mesquite beans, and wild honey.

Key Technology Traditional implements included stone knives, bone tools, bows and arrows, clay pipes for smoking, and nets of yucca fiber. The Havasupai tilled their soil with sticks. Baskets and pottery were used for a number of purposes. Grinding was accomplished by means of a flat rock and rotary mortars.

Trade The Havasupai often traded with the Hopi and other allied tribes, exchanging deerskins, baskets, salt, lima beans, and red hematite paint for food, pottery, and cloth. They also traded with tribes as far away as the Pacific Ocean.

Notable Arts Baskets, created by women, were especially well made. They were used as burden baskets, seed beaters and parching trays, pitch-coated water bottles, and cradle hoods. Brown and unpainted pottery was first dried in the sun, then baked in hot coals.

Transportation Horses entered the region in the seventeenth century.

Dress Buckskin, worked by men, was the main clothing material. Women wore a two-part dress, with a yucca-fiber or textile belt around the waist, and trimmed with hoof tinklers. In the nineteenth century they began wearing ornamental shawls. Moccasins, when worn, were made with a high upper wrapped around the calf. Men wore shirts, loincloths, leggings, headbands, and high-ankle moccasins. Personal decoration consisted of necklaces, earrings of Pueblo and Navajo shell and silver, and occasionally painted faces.

War and Weapons This peaceful people needed no war chiefs or societies. In the rare cases of defensive fighting, the most competent available leader took charge. Traditional allies included the Hualapai and Hopi; enemies included the Yavapai and Western Apache.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The Havasupai Reservation was established from 1880 to 1882, near Supai, Arizona, along the Colorado River, 3,000 feet below the rim of the Grand Canyon. It now consists of roughly 188,000 acres, with year-to-year permits issued for grazing in Grand Canyon National Park and the adjacent National Forest. The tribe adopted a constitution and by-laws in 1939 and a tribal corporate charter in 1946. Men and women serve on the elected tribal council. In 1975, the tribe regained a portion (185,000 acres) of their ancestral homeland along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon.

Economy Tourism constitutes the most important economic activity. The tribe offers mule guides, a campground, a hostel, a restaurant, and a lodge, and they sell baskets and other crafts. Farming has almost entirely disappeared. The tribe owns a significant cattle herd. Some people work for wages at Grand Canyon Village or in federal or tribal jobs. Fearing contamination from a new uranium mine, the tribe has banned mining on tribal lands.

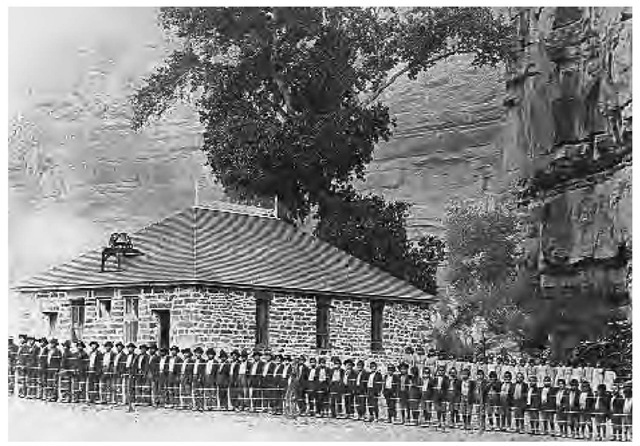

A group of students at the Havasupai Reservation in Arizona. Established between 1880 and 1882 along the Colorado River, 3,000 feet below the rim of the Grand Canyon, the reservation consists of roughly 188,000 acres.

Legal Status The Havasupai are a federally recognized tribal entity.

Daily Life Life among the Havasupai remains a mixture of the old and the new. Unlike many Indian tribes, their reservation includes part of their ancestral land. Most children entering the tribal school (self-administered since 1975) speak only Pai; again, unlike many tribes that focus on learning tribal identity, Havasupai children are encouraged to learn more about the outside world. Students attend school on the reservation through the eighth grade, then move to boarding school in California or to regular public schools.

People continue to celebrate the traditional fall "peach festival," although the time has been changed to accommodate the boarding school schedule. Some people never leave the canyon; many venture out no more than several times a year. The nearest provisions are 100 miles away. Many still ride horses exclusively, although they may be listening to a portable music player at the time. Havasupai people often mix with tourists who wind up in the village at the end of the Grand Canyon’s Hualapai Trail. Some people own satellite dishes and videocassette recorders, but much remains of the old patterns, and intermarriage beyond the Hualapai remains rare. Variants of traditional religion remain alive, while at the same time Rastafarianism is also popular, especially among young men. The people are fighting an ongoing legal battle over uranium pollution of a sacred site in the Kaibab National Forest.