Dakota (Da ‘ ko ta), a Siouan dialect spoken by the Eastern group of the tribe commonly referred to as Sioux. The divisions of the Eastern group include Sisseton ("swamp village," "lake village," or "fishscale village"), Wahpeton ("dwellers among the leaves"), Wahpekute ("shooters among the leaves"), and Mdewakanton ("People of the Mystic Lake"). The latter two divisions are also known as Santee (from Isanati, "knife.") and shared a closely related culture.

The Dakota refer to themselves as Dakota ("ally"), Dakotah Oyate ("Dakota People"), or Ikce Wicasa ("Natural" or "Free People"). The word "Sioux" is derived originally from an Ojibwa word, Nadowe-is-iw, meaning "lesser adder" ("enemy" is the implication), which was corrupted by French voyageurs to Nadoussioux and then shortened to Sioux. Today, many people use the term "Dakota" or, less commonly, "Lakota" to refer to all Sioux people.

All 13 subdivisions of Dakota-Lakota-Nakota speakers (Sioux) were known as Oceti Sakowin, or Seven Council Fires, a term referring to their seven political divisions: Teton (the Western group, speakers of Lakota); Sisseton, Wahpeton, Wahpekute, and Mdewakanton (the Eastern group, speakers of Dakota); and Yankton and Yanktonai (the Central, or Wiciyela, group, speakers of Dakota and Nakota). See also Lakota and Nakota.

Location In the late seventeenth century, the Dakotas lived in Wisconsin and north-central Minnesota, around Mille Lacs. By the nineteenth century they had migrated to the prairies and eastern plains of Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska, and eastern South Dakota. Today, most Dakotas live on reservations in the Dakotas, Nebraska, and Minnesota and in regional cities and towns.

Population Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota speakers numbered about 25,000 in the late seventeenth century. At that time there were approximately 5,000 Dakota speakers. There were about 12,000-15,000 Dakota and Nakota speakers in the late eighteenth century. Today there are at least 6,000 Dakotas living in the United States and Canada.

Language The Eastern group speaks the Dakota dialect of Dakota, a Siouan language.

Historical Information

History The Siouan linguistic family may have originated along the lower Mississippi River or in eastern Texas. Siouan speakers moved to, or may in fact have originated in, the Ohio Valley, where they lived in large agricultural settlements. They may have been related to the Mound Builder culture of the ninth through twelfth centuries. They may also have originated in the upper Mississippi Valley or even the Atlantic seaboard.

Siouan tribes still lived in the southeast, between Florida and Virginia, around the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century. All were destroyed either by attacks from Algonquian-speaking Indians or a combination of attacks from non-Indians and non-Indian diseases. Some fled and were absorbed by other tribes. Some were also sent as slaves to the West Indies.

Dakota-Lakota-Nakota speakers ranged throughout more than 100 million acres of the upper Mississippi region, including Minnesota and parts of Wisconsin, Iowa, and the Dakotas, from the sixteenth to the early seventeenth century. Some of these people encountered French explorers around Mille Lacs, Minnesota, in the late seventeenth century, and Santees were directly involved in the great British-French political and economic struggle. Around that time, conflict with the Cree and Anishinabe, who were well armed with French rifles, plus the lure of great buffalo herds to feed their expanding population, induced bands to begin moving west into the Plains. The people acquired horses around the mid-eighteenth century.

Dakotas were the last to leave, with most bands remaining in prairies of western Minnesota and eastern South Dakota. They also retained many eastern Woodland/western Great Lakes characteristics. Around 1800, the Wahpeton established villages above the mouth of the Minnesota River. Fifty years later they had moved farther upriver and broken into an upper and a lower division. The Mdewakanton and Wahpekute tribes (Santee) established villages around the Mississippi and lower Minnesota Rivers and began hunting buffalo communally, competing with the Sauk, Fox, and other tribes.

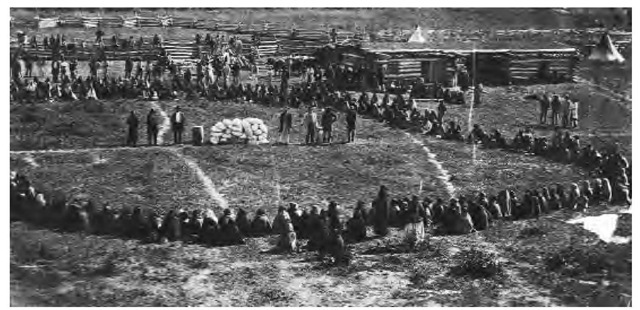

A government agent distributes food rations to Dakota Indians.

Dakotas ceded all land in Minnesota and Iowa in 1837 and 1851 (Mendota and Traverse des Sioux Treaties), except for a reservation along the Minnesota River. Santees were served by a lower agency, near Morton, and Sissetons and Wahpetons by an upper agency, near Granite Falls. At the mercy of dishonest agents and government officials, who cheated them out of food and money, and all but overrun by squatters, the Santees rebelled in 1862. Under the leadership of Ta-oya-te-duta (Little Crow), they killed hundreds of non-Indians.

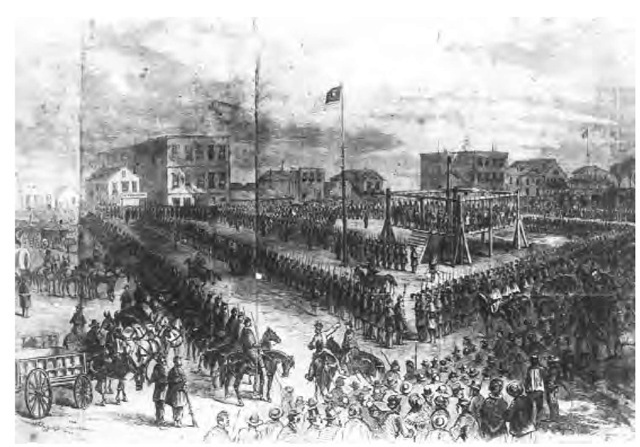

Since many Wahpetons and Sissetons remained neutral (or, as in the case of Chief Wabasha, betrayed their people), and support for the rebellion was not deep, it shortly collapsed. In reprisal, the government hanged 38 Dakotas after President Lincoln pardoned over 250 others and confiscated all Dakota land and property in Minnesota. All previous treaties were unilaterally abrogated. Little Crow himself was killed by bounty hunters in 1863. His scalp and skull were placed on exhibition in St. Paul.

Many Santees fled to Canada and to the West, to join relatives at Fort Peck and elsewhere. Many more died of starvation and illness during this period. Mdewakanton and Wahpekute survivors were rounded up and finally settled at Crow Creek, South Dakota, a place of poor soil and little game, where hundreds of removed Dakotas died within one year. Thus ended the long Santee occupation of the eastern Woodlands/prairie region.

In 1866, Santees at Crow Creek were removed to the Santee Reservation, Nebraska, where living conditions were extremely poor. Most of the land was allotted in 1885. Missionaries, especially Congregationalists and Episcopalians, were influential well into the twentieth century. Most people lived by subsistence farming, hunting, fishing, and gathering.

At the mercy of dishonest agents and government officials who cheated them out of food and money, the Santees rebelled in 1862. This drawing by W. C. Childs depicts the mass hanging of 32 Santee Dakota Indians at Mankato, Minnesota, on December 2, 1862, for their participation in the revolt.

Two reservations were established for Wahpetons and Sissetons around 1867: the Sisseton-Wahpeton Reservation, near Lake Traverse, South Dakota, and the Fort Totten Reservation, at Devil’s Lake. By 1892, two-thirds of the Lake Traverse Reservation had been opened to non-Indians, with the remaining one-third, about 300,000 acres, allotted to individuals. In order not to starve, many sold their allotted land, so that more than half of the latter acreage was subsequently lost. For much of the early twentieth century, people eked out a living through subsistence farming combined with other subsistence activities as well as wages and trust-fund payments.

Several hundred Dakotas left the Santee Reservation in 1869 to settle on the Big Sioux River near Flandreau, South Dakota, renouncing tribal membership at that time. Some federal aid was arranged by a Presbyterian minister, but by and large these people lived without even the meager benefits provided to most Indians. Some Flandreau Indians eventually drifted back to form communities in Minnesota. The official status of these communities was uncertain well into the twentieth century.

Religion Male and female shamans provided religious leadership. Depending on the tribe, their duties might include leading hunting and war parties; curing the sick; foretelling the future, including the weather; and interpreting visions and dreams. Wahpeton shamans also divined the whereabouts of the enemy and lost objects. They performed feats of skill and magic in front of large audiences to impress the public with their powers.

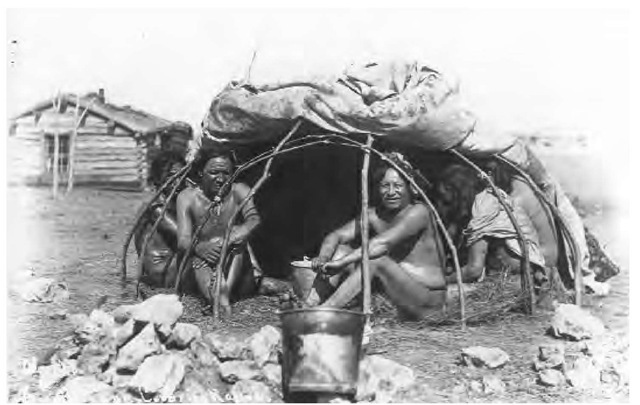

Sissetons and Wahpetons believed in Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit and creator of the universe, as well as other gods and spirits. The secret Wahpeton Medicine Lodge Society performed the Medicine Dance several times a year. Participants used drums, deer hoof rattles, whistles, and sacred pipes carved of pipestone. Other religious activities included vision quests and ritual purification in the sweat lodge. The Sisseton later adopted some Plains ceremonies, such as the Sun Dance.

Religious activities among Dakota Indians included vision quests and ritual purification in the sweat lodge. These men are seated in a sweat lodge with its covering partially raised. Before the advent of tin buckets, water was carried in buffalo bladders into which hot stones were dropped.

Government All but the Wahpekute were divided into seven bands, each usually led by a chief. In more recent times that position was often hereditary. For the same three bands, the akitcita was an elite warrior group that maintained discipline at camp and on the hunt. This police society was distinctive of Siouans and may have originated with them. The Seven Council Fires met approximately annually to socialize and discuss matters of national importance.

Customs Mdewakantons wrapped their dead in skins or blankets and placed them on scaffolds. Remains were taken to a tribal burial grounds after a few months or years and buried in mounds with tools and weapons. Burial mounds were at least several feet high and up to 60 feet in diameter.

Sissetons treated their dead similarly but included tools, weapons, and utensils. Bodies with heads facing south were placed in scaffolds or trees. A horse might be killed for a dead warrior to use in the next life. Murder victims were placed face down in the ground. Mourners cut their hair and slashed their limbs.

Wahpetons buried their dead early on but changed to scaffolds, probably as a result of Sisseton influence. The Dakota bands may once have been clans. Favorite games, usually accompanied by gambling, included lacrosse and shinny. Descent was patrilineal.

Dwellings Dakotas built small, occasionally palisaded villages near lakes and rice swamps when they lived in the Wisconsin-Minnesota area. At that time they lived in large, heavily timbered bark houses with pitched roofs. In winter, some groups lived in small conical houses covered with skins. Both men and women helped build the houses. The Sisseton sometimes used tip is after their move to the prairies.

Diet Siouan people in the Ohio Valley farmed corn, beans, and squash. While still in the Great Lakes region, women grew corn, beans, and squash. People ate turtles, fish, dogs, and large and small game and gathered wild rice. Buffalo, which roamed the area in small herds, was also an important food source. People burned grass around the range and forced the buffalo toward an ambush. The Sisseton, especially, turned more toward buffalo with their westward migration.

Key Technology Bows and arrows were the main hunting weapons. The Sisseton carved pipestone (catlinite) ceremonial pipes and wove rushes into mats. The Wahpeton wove rushes into mats and also wove cedar and basswood fiber bags. All groups made pottery. Fish were either speared or shot with a bow and arrow. Iron-containing clays were pulverized in stone mortars and mixed with gluey material to make paint. Brushes were made of bone, horn, wood, or a tuft of antelope hair mounted on a stick. The flageolet was a common musical instrument.

Trade Depending on time and location, Dakota tribes traded various woodland/prairie/plains goods. Items included wild rice, pottery, and skins and other animal products.

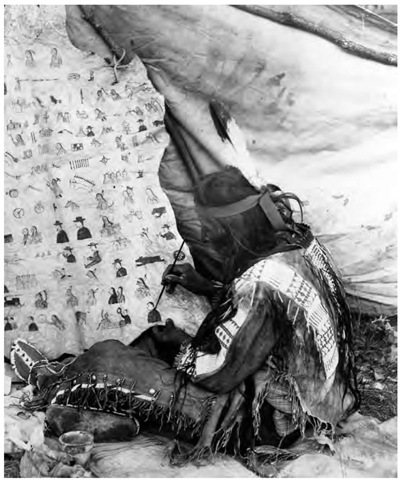

Notable Arts The Dakota made fine painted rawhide trunks. They incised and painted parfleches, pipe pouches, robes, and other items. Women tended to make geometric designs, whereas men made more realistic forms. Clothing was embroidered and, later, beaded.

Transportation The Sisseton made dugout canoes, and the Wahpeton made birch-bark canoes. Most groups obtained horses beginning around 1760, but the eastern groups never had as many as did the western groups.

Dress Most clothing was made from buckskin. In the Woodlands, the people wore breechclouts, dresses, leggings, and moccasins, with fur robes for extra warmth. On the Plains, they decorated their clothing with beads and quillwork in geometric and animal designs.

War and Weapons The idea that the purpose of war was to bring glory to an individual rather than to acquire territory or destroy an enemy people was distinctive to the Siouan people and may have originated with them. Dakotas did not generally fight other Dakotas. The akitcita, known particularly among the Mdewakanton, was an elite warrior group that maintained discipline at camp and on the hunt. The Ojibwa were traditional enemies, at least around the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The Fort Peck Reservation, Roosevelt, Sheridan, and Valley Counties, Montana (Assiniboine-Sioux [Upper Yanktonai and Sisseton-Wahpeton]), established in 1873, consists of about one million acres, about one-quarter of which is tribally owned. Their 1927 constitution is not based on the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). Their representative government, the Tribal Executive Board, dates from 1960. Enrollment in 1992 was 10,500, with 6,700 residents.

Sam Kills Two, a Brule Dakota, paints a winter count in 1926. The death of Turning Bear, killed by a locomotive in 1920, is shown in the second row just above Kills Two’s left foot. Some Plains tribes kept records of events by means of symbolic figures or pictographs.

The Devil’s Lake (formerly Fort Totten) Reservation, Benson, Eddy, Nelson and Ramsey Counties, North Dakota (Sisseton, Wahpeton, and Cuthead Yanktonai), established in 1867, consists of 53,239 acres, most of which have been allotted. There were 4,420 enrolled members in 1992, with about 2,900 in residence. The IRA constitution adopted in 1944 calls for elections to a tribal council.

The Lake Traverse Reservation, Richland and Sargent Counties, North Dakota, and Cadington, Day, Grant, Marshall, and Roberts Counties, South Dakota (Sisseton and Wahpeton), established in 1867, consists of about 105,000 acres. Under a 1934 constitution and by-laws, the people elect district representatives to a tribal council. Tribal enrollment was 10,073 in 1992, with a resident population of 5,306.

The Santee Sioux Reservation, Knox County, Nebraska (Santee), established in 1863, consists of about 3,600 acres. Enrollment in 1992 was about 2,000. In the same year there were 748 residents. A tribal council governs the reservation.

The Flandreau Santee Sioux Reservation, Moody County, South Dakota (Santee), established in 1935, consists of about 2,180 acres. The constitution and by-laws were approved in 1931 and then amended in 1936 to conform to the IRA. Enrolled membership in 1992 was 611 with about 230 residents. An executive committee governs the reservation.

The Lower Sioux Community, Redwood County, Minnesota (Santee), established in 1887, owns 1,742.93 acres. The 1992 enrollment was 750 with about 300 residents. The people elect a community council.

The Prairie Island Community, Goodhue County, Minnesota (Santee), established in 1887, consists of about 534 acres. Enrollment in 1992 was 440, with 56 residents in 1990. A community council is popularly elected.

The Upper Sioux Community, Yellow Medicine County, Minnesota (Sisseton, Wahpeton, Flandreau Santee, Santee, Yankton), established in 1938, consists of 743.57 acres. There were 43 residents in 1990. Political power is exercised by a board of trustees.

The Prior Lake (Shakopee) Community, Scott County, Minnesota (Santee), established in 1969, consists of about 293 acres. Enrollment in 1992 was 227, with 174 residents. A community council governs the community.

The Wabasha Community (Minnesota) consists of 110.24 acres. There are no residents. It was purchased in 1944 as part of the Upper Mississippi Fish and Wildlife Refuge.

Some Wahpetons and other Dakotas also live on Canadian reserves, such as Portage la Prairie, Sioux Valley, Pipestone, and Bird Tail in Manitoba and Fort Qu’appelle, Moose Wood, and Round Plain in Saskatchewan.

Economy The Devil’s Lake Sioux have a plant that makes nonviolent armaments such as camouflage nets. There are also a bingo hall and a casino. Lake Traverse has a bingo hall and casino as well as a plastic bag factory. With an inadequate land base and little industry, many residents of the Santee Sioux Reservation must seek employment in nearby cities and towns. A pharmaceutical company provides a small number of jobs.

The Flandreau Reservation opened the Royal River Casino in 1990. Fort Peck has a bingo hall, and land is leased to non-Indian farmers and ranchers. Fort Peck owns and operates a profitable oil well. They also have other mineral resources and have encouraged industrial development.

The Lower Sioux own a casino, as do Prairie Island (casino and bingo hall), Upper Sioux (casino), and Prior Lake (casino and bingo hall).

Legal Status The Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Reservation, the Devils Lake Sioux Tribe, the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe, the Lower Sioux Indian Community of Minnesota Mdewakanton Sioux Indians, the Prairie Island Indian Community of Minnesota Mdewakanton Sioux Indians, the Santee Sioux Tribe, the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community (Prior Lake), the Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux Tribe (Lake Traverse), and the Upper Sioux Indian Community are federally recognized tribal entities.

Daily Life The Wahpeton and Sisseton people are closely related, in part through much intermarriage. At Lake Traverse, Sisseton-Wahpeton Community College opened in 1979, and Tiospa Zina High School emphasizes tribal values. Many people speak Dakota at Devil’s Lake, which is a relatively traditional community. They sponsor a powwow in July. The Native American Church and Sacred Pipe ceremony, among other religious practices, remain active. People on the Santee Reservation resisted a casino in favor of cultural revival. Flandreau received new homes, irrigation, and health care facilities in the 1960s.