Apache comes from the Zuni Apachu, meaning "enemy." These people are properly known as Ndee, or Dine’e![]() , "the People." Western Apache is a somewhat artificial designation given to an Apache tribe composed, with some exceptions, of bands living in Arizona. After 1850 these bands were primarily the San Carlos, White Mountain, Tonto (divided into Northern and Southern Tonto by anthropologists), and Cibecue.

, "the People." Western Apache is a somewhat artificial designation given to an Apache tribe composed, with some exceptions, of bands living in Arizona. After 1850 these bands were primarily the San Carlos, White Mountain, Tonto (divided into Northern and Southern Tonto by anthropologists), and Cibecue.

Location Traditionally, Western Apache bands covered nearly all but the northwesternmost quarter of Arizona. Their territory encompassed an extreme ecological diversity. Today’s reservations include Fort Apache (Cibecue and White Mountain); San Carlos (San Carlos); Camp Verde, including Clarkdale and Middle Verde (mostly Tonto; shared with the Yavapai); and Payson. Tonto also live in the Middle Verde, Clarkdale, and Payson communities.

Population Perhaps 5,000 Western Apaches (all groups) lived in Arizona around 1500. In 1992 the populations were as follows: San Carlos, 7,562 (including some Chiricahuas); Fort Apache, 12,503; Camp Verde, 650 (with the Yavapai); Payson, 92; Fort McDowell (Apache, Mojave, Yavapai), 765.

Language Apaches spoke Southern Athapaskan, or Apachean.

Historical Information

History Ancestors of today’s Apache Indians began the trek from Asia to North America in roughly 1000 B.C.E. Most of this group, which included the Athapaskans, was known as the Nadene. By 1300, the group that was to become the Southern Athapaskans (Apaches and Navajos) broke away from other Athapaskan tribes and began migrating southward, reaching the American Southwest around 1400 and crystallizing into separate cultural groups.

The Apaches generally filtered into the mountains surrounding the Pueblo-held valleys. This process ended in the 1600s and 1700s, with a final push southward and westward by the Comanches. Before contact with the Spanish, the Apaches were relatively peaceful and may have engaged in some agricultural activities. The Western Apache bands avoided much contact with outsiders until the mid-eighteenth century. The People became semisedentary with the development of agriculture, which they learned from the Pueblos.

Having acquired the horse, the Western Apache groups established a trading and raiding network with at least a dozen other groups, from the Hopi to Spanish settlements in Sonora. Although the Spanish policy of promoting docility by providing liquor to Native Americans worked moderately well from the late eighteenth century through the early nineteenth, Apache raids remained ongoing into the nineteenth century. By 1830, the Apache had drifted away from the presidios and resumed a full schedule of raiding.

Following the war between Mexico and the United States (1848), the Apaches, who did their part to bring misery to Mexico, assumed that the Americans would continue to be their allies. The Apaches were shocked and disgusted to learn that their lands were now considered part of the United States and that the Americans planned to "pacify" them. Having been squeezed by the Spanish, the Comanches, the Mexicans, and now miners, farmers, and other land-grabbers from the United States, some Apaches were more than ever determined to protect their way of life.

Throughout the 1850s most of the anti-Apache attention was centered on the Chiricahua. The White Mountain and Cibecue people never fought to the finish with the Americans; out of range of mines and settlements, they continued their lives of farming and hunting. When Fort Apache was created (1863), these people adapted peacefully to reservation life and went on to serve as scouts against the Tontos and Chiricahuas.

The Prescott gold strike (1863) heralded a cycle of raid, murder, and massacre for the Tonto. By 1865 a string of forts ringed their territory; they were defeated militarily eight years later. A massacre of San Carlos (Aravaipa) women in 1871 led to Grant’s "peace policy," a policy of concentration via forced marches. The result was that thousands of Chiricahuas and Western Apaches lived on the crowded and disease-ridden San Carlos Reservation. There, a handful of dissident chiefs, confined in chains, held out for the old life of freedom and self-respect. The Chiricahua Victorio bolted with 350 followers and remained at large and raiding for years. More fled in 1881. By 1884 all had been killed or had returned, at least temporarily. In general, the Western Apaches remained peaceful on the reservations while corrupt agents and settlers stole their best land.

The White Mountain people joined Fort Apache in 1879. As the various bands were spuriously lumped together, group distinctions as well as traditional identity began to break down. A man named Silas John Edwards established a significant and enduring religious cult at Fort Apache in the 1920s. Though not exactly Christian, it did substitute a new set of ceremonies in place of the old ones, contributing further to the general decline of traditional life. In 1918 the government issued cattle to the Apaches; lumbering began in the 1920s. In 1930, the government informed the Apaches that a new dam (the Coolidge) would flood old San Carlos. All residents were forced out, and subsistence agriculture ended for them. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) provided them with cattle and let all Anglo leases expire; by the late 1930s these Indians were stockmen.

Religion Apache religion is based on a complex mythology and features numerous deities. The sun is the greatest source of power. Culture heroes, like White-Painted Woman and her son, Child of the Water, also figure highly, as do protective mountain spirits (ga’an). In fact, the very stories about these subjects are considered sacred. The latter are represented as masked dancers (probably evidence of Pueblo influence) in certain ceremonies, such as the four-day girls’ puberty rite. (The boys’ puberty rite centered on raiding and warfare.)

Supernatural power, inherent in certain plants, animals, minerals, celestial bodies, and weather, is both the goal and the medium of most Apache ceremonialism. These forces could become involved, for better or worse, in affairs of people. The ultimate goal of supernatural power was to facilitate the maintenance of spiritual strength and balance in a world of conflicting forces. Shamans facilitated the acquisition of power, which could, by the use of songs, prayers, and sacred objects, be used in the service of war, luck, rainmaking, or life-cycle events. Detailed and extensive knowledge was needed to perform ceremonials; chants were many, long, and very complicated. Power could also be evil as well as good and was to be treated with respect. Witchcraft, as well as incest, was an unpardonable offense. Finally, Apaches believed that since other living things were once people, we are merely following in the footsteps of those who have gone before.

Government Each of the Western Apache tribes was considered autonomous and distinct, although intermarriage did occur. Tribal cohesion was minimal; there was no central political authority. A "tribe" was based on a common territory, language, and culture. Each was made up of between two and five bands of greatly varying size. Bands formed the most important Apache unit, which were in turn composed of local groups (35-200 people in extended families, themselves led by a headman) headed by a chief. The chief lectured his followers before sunrise every morning on proper behavior. His authority was based on his personal qualities and perhaps his ceremonial knowledge. Decisions were taken by consensus. One of the chief’s most important functions was to mitigate friction among his people.

Customs Women were the anchors of the Apache family. Residence was matrilocal. Besides the political organization, society was divided into a number of matrilineal clans, which further tied families together. Apaches in general respected the elderly and valued honesty above most other qualities. Gender roles were clearly defined but not rigidly enforced. Women gathered, prepared, and stored food; built the home; carried water; gathered fuel; cared for the children; tanned, dyed, and decorated hides; and wove baskets. Men hunted, raided, and waged war. They also made weapons, were responsible for their horses and equipment, and made musical instruments. Western Apaches generally planted crops and gathered food in summer, harvested and hunted in fall, and returned to winter camps for raiding in winter.

Girls as well as boys practiced with the bow and arrow, sling, and spear, and both learned to ride expertly. The four-day girls’ puberty ceremony was a major ritual (at which mountain spirits appeared) as well as a major social event. Traditional games, such as hoop and pole, often also involved supernatural powers. Marriages were often arranged, but the couple had the final say. Although actual marriage ceremonies were brief or nonexistent, the people practiced a number of formal preliminary rituals, designed to strengthen the idea that a man owed deep allegiance to his future wife’s family. Out of deference, married men were not permitted to speak directly with their mothers-in-law. Divorce was relatively easy to obtain.

All Apaches had a great fear of ghosts. A dead person’s dwelling was abandoned, and his or her name was never spoken again. Burial followed quickly.

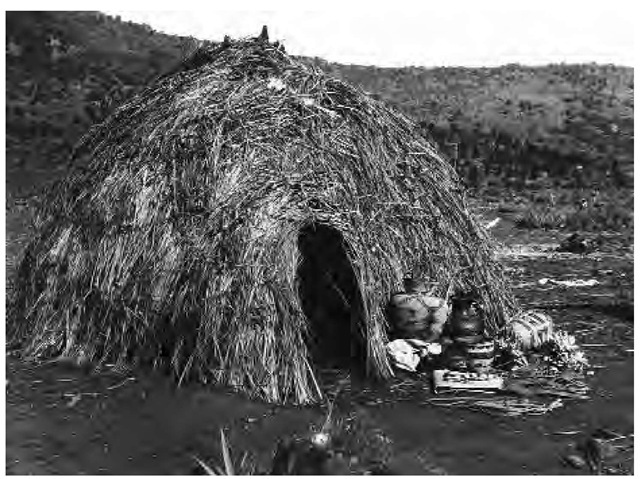

Dwellings Women built the homes. Most Western Apache people lived in dome-shaped wikiups, made of wood poles covered with bear grass, which they covered with hides in bad weather. Brush ramadas were used for domestic activities.

Diet Western Apache groups were primarily hunters and gatherers. They hunted buffalo prior to the sixteenth century, and afterward they continued to hunt deer, antelope, mountain lion, elk, porcupine, and other game. They did not eat bear, turkey, or fish.

Most Western Apache lived in dome-shaped wickiups made of wood poles covered with bear grass. Outside this brush hut are Apache baskets. Other fine arts included cradle boards and pottery.

Wild foods included agave shoots, flowers, and fruit; berries; seeds; nuts; honey; and wild onions, potatoes, and grasses. Nuts and seeds were often ground into flour. The agave or century plant was particularly important. Baking its base in rock-lined pits for several days yielded mescal, a sweet, nutritious food, which was dried and stored. About one-quarter of their diet (slightly more among the Cibecue) came from agricultural products (corn, beans, and squash), which they both grew and raided the pueblos for. They also drank a mild corn beer called tulupai.

Key Technology Items included excellent baskets (pitch-covered water jars, cradles, storage containers, and burden baskets); gourd spoons, dippers, and dishes; and a sinew-backed bow. Storage bags were also made of buckskin. The People made musical instruments out of gourds and hooves. The so-called Apache fiddle, a postcontact instrument, was played with a bow on strings. Moccasins were sewn with plant fiber attached to mescal thorns.

Trade By the mid-eighteenth century, the horse had enabled the Apache to establish a trading and raiding network with at least a dozen other groups, from the Hopi and other Pueblos to Spanish settlements in Sonora. From the Spanish, the Apache acquired (in addition to the horse) the lance, saddle and stirrup, bridle, firearms, cloth, and playing cards.

Notable Arts Fine arts included basketry (bowls, storage jars, burden baskets, and pitch-covered water jugs) designed with vegetable dyes, hooded cradle boards, and black or dark gray pottery.

Transportation Dogs served as beasts of burden before Spanish horses arrived in the seventeenth century.

Dress The Western Apache traditionally wore buckskin clothing and moccasins. As they acquired cotton and later wool through trading and raiding, women tended to wear two-piece calico dresses, with long, full skirts and long blouses outside the skirt belts. They occasionally carried knives and ammunition belts. Girls wore their hair over their ears, shaped around two willow hoops. Some older women wore hair Plains-style, parted in the middle with two braids. Men’s postcontact styles included calico shirts, muslin breechclouts with belts, cartridge belts, thigh-high moccasins, and headbands; women wore Mexican-style cloth dresses. Blankets as well as deerskin coats were used in winter.

War and Weapons Historically, the Apache made formidable enemies. Raiding was one of their most important activities. The purpose of raiding, in which one sought to avoid contact with the enemy, was to gain wealth and honor as well as to assist the needy. It differed fundamentally from warfare, which was undertaken primarily for revenge. Western Apaches raided the Maricopa, Pai, O’odham, and Navajo (trading and raiding). Their allies included the Quechan, Chemehuevi, Mojave, and Yavapai. Since the Apache abhorred mutilation, scalping was not a custom, although a killing required revenge. At least one shaman accompanied all war parties. Mulberry, oak, or locust bows were sinew backed; arrow tips were of fire-hardened wood or cane. Other weapons included lances, war clubs, and rawhide slings.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations San Carlos (1871; 1.87 million acres) and Fort Apache (1871; 1.66 million acres) Reservations were divided administratively in 1897. Both accepted reorganization under the Indian Reorganization Act (1934) and elect tribal councils. Other Western Apache reservations and communities include Camp Verde (shared with the Yavapai; 640 acres), Fort McDowell (a Yavapai reservation also shared with Mojave Indians; 24,680 acres), Clarkdale, and Payson (Yavapai-Apache; 85 acres; established 1972).

Economy Important economic activities at San Carlos include cattle ranching, farming, logging, mining (asbestos and other minerals) leases, basket making, and off-reservation wage work. In general the economy at San Carlos is depressed. At Fort Apache the people engage in cattle ranching, timber harvesting, agriculture, operating the Sunrise resort, selling recreation permits, and leasing summer cabins. Unemployment at Fort Apache is relatively low. Recreation is the main resource at Camp Verde.

Legal Status The San Carlos Apache Tribe, run as a corporation; the Tonto Apache Indians; and the White Mountain Apache Tribe are federally recognized tribal entities. The Payson Community of Yavapai-Apache Indians is a federally recognized tribal entity.

Daily Life San Carlos remains poor, with few jobs. Still, even if it means continuing in poverty, many Apaches resist acculturation: The ability to remain with family and friends remains paramount. The language and many traditions and ceremonies remain an important part of people’s daily lives. Increasing off-reservation work, however, has opened the door to additional serious social problems. Management of San Carlos has remained in BIA hands, leaving Indians with the usual problem of being stripped of their heritage and institutions with no replacement or training or responsibility for their own affairs. The people of San Carlos are fighting a University of Arizona telescope bank on their sacred Mount Graham.

The Cibecue are the most traditional people at conservative Fort Apache. Nuclear families are now more important than extended families and local groups, but clans remain key, especially for the many extant ceremonies. Alcoholism and drug use are a large problem on the reservation. Public schools at both reservations have strong bilingual programs; educated leaders are a high need and priority (education levels remain quite low on both reservations). The Tonto have intermarried extensively with the Yavapai.