Anishinabe![]() , "People," are also variously known by the band names Ojibwe/ Ojibwa/Ojibway/Chippewa, Mississauga, and Salteaux. The name Ojibwa means "puckered up," probably a reference to a style of sewn moccasin. With the Potawatomi and Ottawa, with whom they may once have been united, some groups were part of the Council of Three Fires in the nineteenth century. Northern groups had a Subarctic as well as a Woodlands cultural orientation (see Chapter 9, especially Cree). See also Ojibwa, Plains (Chapter 6); Ottawa.

, "People," are also variously known by the band names Ojibwe/ Ojibwa/Ojibway/Chippewa, Mississauga, and Salteaux. The name Ojibwa means "puckered up," probably a reference to a style of sewn moccasin. With the Potawatomi and Ottawa, with whom they may once have been united, some groups were part of the Council of Three Fires in the nineteenth century. Northern groups had a Subarctic as well as a Woodlands cultural orientation (see Chapter 9, especially Cree). See also Ojibwa, Plains (Chapter 6); Ottawa.

Location Anishinabe groups lived north of Lake Huron and northeast of Lake Superior (present-day Ontario, Canada) in the early seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century, northern Ojibwas lived between the Great Lakes and Hudson Bay, and the Lake Winnipeg Salteaux lived just east and south of that body of water.

Today, there are Anishinabe communities and reservations in central and northern Michigan, including the Upper Peninsula; northern Wisconsin; northern and central Minnesota; northern North Dakota; northern Montana; and southern Ontario. Anishinabe also live in regional cities and towns.

Population The people numbered at least 35,000, but perhaps more than double that figure, in the early seventeenth century. There were roughly 125,000 enrolled Anishinabe in the United States in the mid-1990s, including about 48,000 in Minnesota, at least 30,000 in Michigan, 25,000 members of the Turtle Mountain Band in North Dakota, 16,500 in Wisconsin, and 3,100 at Rocky Boy Reservation in Montana, plus other communities in Montana and elsewhere in the United States. There were about 60,000 Anishinabe in Canada in the mid-1990s, excluding Metis.

Language The various Anishinabe groups spoke dialects of Algonquian languages.

Historical Information

History The Anishinabe probably came to their historical location from the northeast and had arrived by about 1200. They encountered Frenchmen in the early seventeenth century and soon became reliable French allies. From the later seventeenth century on, the people experienced great changes in their material and economic culture as they became dependent on guns, beads, cloth, metal items, and alcohol.

Pressures related to the fur trade, including Iroquois attacks, drove the Anishinabe to expand their territory by the late seventeenth century. With French firearms, they pressured the Dakota to move west toward the Great Plains. They also drove tribes such as the Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo from Michigan and replaced the Huron in lower Michigan and extreme southeast Ontario. With the westward march of British and especially French trading posts, Ojibwa bands also moved into Minnesota and north-central Canada (Lake of the Woods and the Red River area), displacing Siouan and other Algonquian groups (such as the Cheyenne).

As early as the late seventeenth century, Anishinabe bands had moved west into the Lake Winnipeg/North Dakota region. Many people intermarried with Cree Indians and French trappers and became known as Metis, or Mitchif. By the eighteenth century, Anishinabe bands stretched from Lake Huron to the Missouri River.

The people were most deeply involved in the fur (especially beaver) trade during the eighteenth century. They fought the British in the French and Indian War and in Pontiac’s rebellion. In 1769, in alliance with neighboring tribes, they utterly defeated the Illinois Indians. They fought with the British in the Revolutionary War. Following this loss, they kept up anti-American military pressure, engaging the non-natives in Little Turtle’s war, Tecumseh’s rebellion, and the War of 1812.

By the early nineteenth century, scattered, small hunter-fisher-gatherer bands of northern Ojibwa and Salteaux were located north and west of the Great Lakes. These people experienced significant changes from the early nineteenth century, such as a greater reliance on fish and hare products and on non-native material goods.

The Plains Ojibwe (Bungi) had moved west as far as southern Saskatchewan and Manitoba and North Dakota and Montana. They adopted much of Great Plains culture. The southeastern Ojibwe (Mississauga), living in northern and southern Michigan and nearby Ontario, were hunters, fishers, gatherers, and gardeners. They also made maple sugar and, on occasion, used wild rice. Their summer villages were relatively large. Finally, the southwestern Ojibwe had moved into northern Wisconsin and Minnesota following the departing Dakotas. They depended on wild rice as well as hunting, fishing, gathering, gardening. and maple sugaring.

Anishinabe living in the United States ceded much of their eastern land to that government in 1815 upon the final British defeat. Land cessions and the establishment of reservations in Wisconsin and Minnesota followed during the early to mid-nineteenth century. Two small bands went to Kansas in 1839. In the 1860s, some groups settled with the Ottawa, Munsee, and Potawatomi in the Indian Territory.

Michigan and Minnesota Anishinabe groups (with the exception of the Red Lake people) lost most of their land (90 percent or more in many cases) to allotment, fraud, and other irregularities in the mid-to late nineteenth century. They also suffered significant culture loss as a result of government policies encouraging forced assimilation. In the late nineteenth century, many southwestern Ojibwe worked as lumberjacks. Many in the southeast concentrated more on farming, although they continued other traditional subsistence activities when possible. Transition to non-native styles of housing, clothing, and political organization was confirmed during this period.

Plains Ojibwa took part in the Metis rebellion of Louis Riel in 1869-1870. These groups were finally settled on the Turtle Mountain Reservation in the late nineteenth century and on the Rocky Boy Reservation in the early twentieth century. Around the turn of the century, the Turtle Mountain Chippewa, led by Chief Little Shell, worked to regain land lost in 1884 and to reenroll thousands of Metis whom the United States had unilaterally excluded from the tribal rolls. In 1904, the tribe received $1 million for a 10-million-acre land claim, a settlement of 10 cents an acre. Soon thereafter, most of the Turtle Mountain land was allotted. One result of that action was that many people, denied adequate land, were forced to scatter across the Dakotas and Montana. Most of the allotments were later lost to tax foreclosure, after which the tribal members, now landless, drifted back to Turtle Mountain.

The growing poverty of Michigan bands was partially reversed after most accepted the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) in the 1930s and the United States reassumed its trust relationship with them. Many of these people moved to the industrial cities of the Midwest, especially in Michigan and Wisconsin, after World War II, although most retained close ties with the reservation communities.

Among the northern Ojibwa, bands had made treaties with the Canadian government since the mid-nineteenth century. The Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in the 1880s and the Canadian National Railway around 1920. Supply operations changed again during the 1930s, when "bush planes" began flying. Many people began growing small gardens at that time as well.

Religion Some groups may have believed in the existence of an overarching supreme creative power. All animate and inanimate objects had spirits that could be good or evil (the latter, like the cannibalistic Windigo, were greatly feared). People attempted to keep the spirits happy through prayer and by the ritual use of tobacco and the intervention of shamans. Tobacco played a significant role in many rituals.

By fasting and dreaming in a remote place, young men sought a guardian spirit that would assist them throughout their lives. In general, dreams were considered of extreme importance. There was probably little religious ceremonialism before people began dying in unprecedented numbers as a result of hitherto unknown diseases of Old World origin. The Midewiwin or Medicine Dance was a graded curing society that probably arose, except among the northern Ojibwa, in response to this development.

Membership in the Midewiwin was gained by experiencing particular visions or dreams. Candidates received a period of instruction and paid certain fees. Once a year, a secret meeting lasting several days was held in a special long lodge to initiate new members, who could be men or women. Initiates were shot with a sacred white shell, through which supernatural power entered the body, and were then restored by a priest. One member recorded the proceedings by carving and painting bark scrolls. Members wore special medicine bags around their necks. Initiates did not become shamans, but many were cured through entering the society; members also achieved greater supernatural power as well as prestige.

Bears were revered and were the focus of a special ceremony. Shamans, usually older men, cured the sick with recourse to spiritual power, and herbalists offered effective cures using hundreds of local plants. Several degrees of shaman were recognized. Among the Lake Winnipeg Salteaux, shamans cured disease by using sucking tubes, sometimes after communicating with their spirit helpers in a special shaking tent. These shamans engaged in contests for authority by showing off their evil powers. People also observed special first-fruits ceremonies over wild rice and bear.

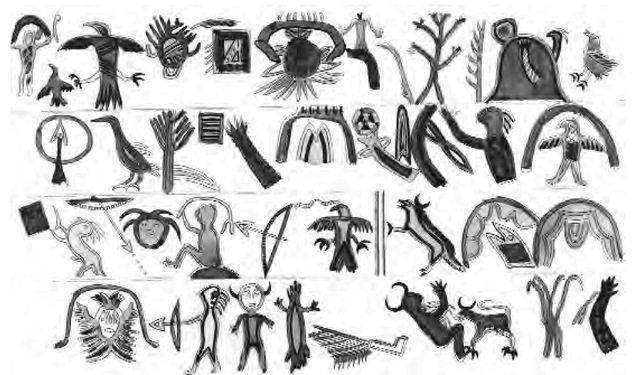

These Ojibwa pictographs depict the sequence for invocations, offerings, and songs for a particular ritual.

Government Men led autonomous bands of perhaps 300-400 people on the basis of both family and ability. Bands were related by marriage but never politically united. Band headman were often war captains but had little direct authority before the fur trade period; for their own advantage, traders worked to increase the power of the headman. These efforts ultimately led to the creation of a patrilineal line of chiefs.

Customs About 15-23 patrilineal clans were linked into the larger divisions. Bands came together in villages during summer and dispersed for the winter hunting season. Within the context of a social organization that was relatively egalitarian, there were people with higher status than others, such as chiefs, accomplished warriors, and shamans.

Infants spent most of their first year on a cradle board with a moss "mattress." Names were ultimately spirit derived. A close relationship existed between the namer and the named. Children were raised with little harsh discipline.

Although a special feast was held to celebrate a boy’s first kill, the major male puberty rite was the vision quest, which entailed a four-day fast deep in the forest to await a propitious dream. At that time he received a guardian spirit power that could be used for good or evil; with the spirit came various names and songs. Contact with the spirit was maintained throughout the man’s life by means of food offerings and tobacco. Girls might also have visions, but they were not generally required to undergo a quest.

Girls were chaperoned at all times. A man might play a flute to court a prospective wife, who was likely chosen by his parents. A man brought food to the future wife’s family to formalize the engagement. Eventually they moved into their own lodge. Important men might have more than one wife. Divorce was easy to obtain on grounds as basic as incompatibility.

Corpses were washed and well presented. Wrapped in birch bark, they were removed from the wigwam, after a period of lying in state, through an opening in the west side. A priest gave a funeral ceremony, after which the body was buried with tools and equipment. The soul was said to travel for four days to a happy location in the west. The mourning period lasted one year.

The Anishinabe enjoyed regular visiting as well as social dancing (although on such occasions men often danced apart from women). They also enjoyed various sports, such as lacrosse and a game in which they threw a pole along frozen snow, and contests; gambling invariably played a part in these activities. Lacrosse was rough and carried religious overtones.

Dwellings The traditional Anishinabe dwelling was a domed wigwam of cattail mats or birch bark over a pole frame. There was a smoke hole in the center over the fire. The doorway was covered with bark, hide, or a blanket. Mats and furs were placed around the sides for sleeping and storage. Floors were covered with cedar inner bark, bullrush mats, or, in the north, boughs.

There were also larger, elliptical wigwams that housed several families. These had a fireplace at either end. Hunters also used temporary bark-covered A-frame lodges, and people built smaller sweat lodges, used for purification or curing, as well as menstrual huts and Midewiwin lodges.

Diet Women grew small gardens of corn, beans, and squash in the south. Men hunted and trapped a variety of large and small game, mostly in winter, as well as birds and fowl. Meat was roasted, stone boiled, or dried and stored. Some was dried and mixed with fat and chokecherries to make pemmican, an extremely nourishing, long-lasting food. Men fished year round, especially for sturgeon, sometimes at night by the light of flaming birch-bark torches. People also ate shellfish where available. Dog was often served at feasts.

In the fall, women in canoes gathered wild rice, which became a staple in the Anishinabe southwest and important as well around Lake Winnipeg. Wild rice was actually a grass with an edible seed that could be knocked into the canoe with sticks. It was stored and eaten after being dried, parched, and winnowed. They also gathered a variety of berries, fruits, and nuts, and some groups collected maple sap for sugar, which they used as a seasoning and in water. Northern Ojibwas had access neither to wild rice nor to maple sap.

Key Technology Most items were made of wood and birch bark, but people also used stone, bone, and possibly some pottery. Important material items included birch-bark containers and dishes; water drums, flutes, tambourines, and rattles; cattail, cedar, and bulrush mats; and basswood twine and bags. Fishing equipment included nets, spears, and wood or bone lures and hooks. Lake Winnipeg people made distinctive black steatite pipes as well as sturgeon-skin containers.

Trade Trade items included elm-bark bags and assorted birch-bark goods, carved wooden bowls, food, and maple sugar. As they expanded west, the people began to trade Woodland items for buffalo-derived products.

Notable Arts Clothing and medicine bags were decorated with quillwork. Men carved wooden utilitarian as well as religious items (figurines). Pattern designs were bitten into thin birch-bark sheets. The Anishinabe were also known for their soft elm-bark bags. Lake Winnipeg women made fine moose-hide mittens, richly decorated in beads. As with many native peoples, storytelling evolved to a fine art.

Transportation Men made birch-bark canoes and snowshoes. Horses were acquired in the late eighteenth century. Northern Ojibwas used toboggans and canoe-sleds, sometimes hauled by large dogs, from the nineteenth century on.

Dress Dress varied according to location. Most clothing was made of buckskin. Ojibways tended to color their clothing with red, yellow, blue, and green dyes. In the southwestern areas, women wore woven fiber shirts under a sleeveless dress. Other clothing included breechclouts, leggings, robes, and moccasins, the last often dyed and featuring a distinctive puckered seam. Fur garments were added in cold weather. Both men and women tended to wear their hair long and braided.

The southeastern Ojibwe, living in northern and southern Michigan and nearby Ontario, were hunters, fishers, gatherers, and gardeners as well as makers of maple sugar and, on occasion, users of wild rice. This nineteenth-century drawing by Seth Eastman depicts the Ojibwa harvesting wild rice.

War and Weapons The Anishinabe were generally effective but unenthusiastic fighters. They were traditional allies of the Ottawa and Potawatomi; their enemies included the Iroquois and Dakota. Battles were fought on land as well as occasionally from canoes. Weapons included the knobbed wooden war club, bow and arrow, knife, and moose-hide shield. Enemies were generally killed in battle. Some were ritually eaten. Warriors sometimes exchanged their long hair for a scalp lock.

The Anishinabe ("Original People") are also variously known by the band names Ojibwe/Ojibwa/Ojibway/Chippewa, Mississauga, and Salteaux. This Chippewa man is shown mending his birch-bark canoe (1887). Men fished year-round, especially for sturgeon, sometimes at night by the light of flaming birch-bark torches.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The following are Anishinabe reservations in Michigan:

L’Anse Reservation (Keweenaw Bay, L’Anse, and Otonagan Bands), Baraga County, established in 1854, consists of about 13,000 acres of land, almost two-thirds of which is allotted. There were about 3,100 enrolled members in the early 1990s. The 1990 Indian population was 724.

The Lac Vieux Desert Reservation, Gogebic County, consists of 104 acres of land. The 1990 Indian population was 119. This band had an enrollment of about 240 in the early 1990s. The reservation remains officially unrecognized.

The Bay Mills Indian Reservation (Bay Mills and Sault Ste. Marie Bands), Chippewa County, established in 1850, consists of 2,209 acres of land. The 1990 Indian population was 403. Enrolled membership was about 950 in the early 1990s.

The Sault Ste. Marie Reservation (Sault Ste. Marie Band), Alger, Chippewa, Mackinac, and Schoolcraft Counties, owns 293 acres of land. The 1990 Indian population was 554. There were about 20,630 enrolled band members in the early 1990s. The reservation remains officially unrecognized.

Isabella Reservation and Trust Lands, Isabella and Aranac Counties (Saginaw Chippewa Tribe), established in 1864, contains 1,184 acres, about half of which is tribally owned. A ten-member tribal council is elected at large. The 1990 Indian population was 790. This band had almost 2,200 enrolled members in the early 1990s.

The Grand Traverse Reservation (Ottawa and Chippewa), Leelanau County, consists of about 600 acres of land. The 1990 Indian population was 208. The tribe had about 2,300 members in the early 1990s. The reservation remains officially unrecognized.

The Burt Lake (State) Reservation (Ottawa and Chippewa), Brutus County, consists of about 20 acres. There were over 500 enrolled Chippewas and Ottawas in the early 1990s.

The Anishinabe communities in Minnesota, which are member reservations of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, are self-governed by an elected tribal council or business committee, in cooperation with local councils. Each community is also represented in an overall tribal executive committee, headquartered at Cass Lake community, Leech Lake. Red Lake Reservation is self-governing. The communities are as follows:

Nett Lake (Bois Forte) Reservation (Deer Creek Band), Koochiching and St. Louis Counties, established in 1854, consists of almost 42,000 acres. The 1990 Indian population was 345.

Fond du Lac Reservation, Carlton and St. Louis Counties, established in 1854, consists of almost 22,000 acres. The 1990 Indian population was 1,102.

Grand Portage Reservation, Cook County, established in 1854, consists of almost 45,000 acres. The 1990 Indian population was 206.

Leech Lake Reservation (Mississippi and Pilanger Bands), Beltrami, Cass, Hubbard, and Itasca Counties, established in 1855, consists of roughly 27,500 acres. The 1990 Indian population was 3,390.

Mille Lacs Reservation, Aitkin, Crow Wing, Kanabec, Mille Lacs, and Pine Counties, established in 1855, consists of almost 4,000 acres. The 1990 Indian population was 428.

White Earth Reservation, Blecker, Clearwater, and Mahnomen Counties, established in 1867, consists of roughly 56,000 acres. The 1990 Indian population was 2,759.

Red Lake Reservation, Beltrami, Clearwater, Koochiching, Lake of the Woods, Marshall, Pennington, Polk, Red Lake, and Roseau Counties, established in 1863, consists of roughly 564,000 acres of land. There were almost 8,000 enrolled members of this band in the early 1990s. The 1990 Indian population was 3,601.

The following are reservations of the Lake Superior Tribe (Wisconsin) of Chippewa Indians. Each is governed and administered by an IRA-style tribal council of from 5 to 12 members, headed by an executive officer. Tribal courts are also in the process of expanding their authority to cover welfare and environmental issues. The communities are also members of regional organizations such as the Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council.

Bad River Reservation, Ashland and Iron Counties, established in 1854, consists of about 56,000 acres, less than half of which is tribally owned. The 1990 Indian population was 868. Tribal membership in the early 1990s was about 4,500 people.

Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation and Trust Lands, Sawyer, Burnett, and Washburn Counties, established in 1854, consists of about 48,000 acres, less than half of which is tribally owned. The 1990 Indian population was 1,769. Tribal membership in the early 1990s was about 4,000 people.

Lac du Flambeau Reservation, Iron, Oneida, and Vilas Counties, established in 1854, consists of almost 45,000 acres, about two-thirds of which is tribally owned. The 1990 Indian population was 1,431. Tribal membership in the early 1990s was about 2,700 people.

Red Cliff Reservation and Trust Lands, Bayfield County, established in 1854, consists of almost 75,000 acres, about three-quarters of which is tribally owned. The 1990 Indian population was 727. Tribal membership in the early 1990s was about 2,800 people.

The St. Croix Reservation and the Sokaogon Community and Trust Lands are also located in Wisconsin. St. Croix Reservation, Barron, Burnett, and Polk Counties, established in 1938, consists of about 2,200 acres, all of which is tribally owned. The 1990 Indian population was 459. Tribal membership in the early 1990s was about 750 people. The community is governed by a tribal council with officers.

Sokaogon Community and Trust Lands (Mole Lake Band), Forest County, established in 1938, consists of about 1,900 acres, all of which is tribally owned. The 1990 Indian population was 311. Tribal membership in the early 1990s was about 1,400 people. The community is governed by a tribal council with officers.

Other communities are in Montana and the Dakotas. The Rocky Boy Chippewa-Cree Reservation (1,485 resident Indians in 1990) and Trust Lands (397 resident Indians in 1990), located in Chouteau and Hill Counties, Montana, established in 1916, contains 108,015 acres. The tribe is governed by a written constitution delegating authority to the Chippewa-Cree Business Committee. There is also a tribal court. Roughly half of the population lives off of the reservation.

The Little Shell people, some of whom are of Cree descent, had a 1990 population of 3,300. They are governed by a tribal council under a constitution. Their main offices are in Havre and Helena, Montana. They are related to scattered groups of landless Chippewas living in and near Lewistown, Montana.

There is also a community of Chippewa, established during the process of allotting the Turtle Mountain Reservation, living in eastern Montana. The seat of their government is in Trenton, North Dakota.

The Turtle Mountain Reservation and Trust Lands, Rolette, Burke, Cavalier, Divide, McLean, Mountrail, and Williams Counties, North Dakota, and Perkins County, South Dakota, established in 1882, contains over 45,000 acres, of which about 30 percent is controlled by non-Indians. The 1990 resident Indian population was 6,770. The reservation is governed by an elected nine-member tribal council under a 1959 constitution and by-laws. Headquarters are located in Belcourt, North Dakota.

Canada recognizes over 130 Indian communities that are wholly or in part Anishinabe. They are located in Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, and Saskatchewan and include Walpole Island (Ontario), where Anishinabe Indians live with some Potawatomis and Ottawas.

Economy All of the acknowledged Michigan tribes operate successful casinos. Minnesota reservations operate at least one casino each. There is a women’s cooperative that produces and sells wild rice and crafts at White Earth, Minnesota, and there is a fisheries cooperative at Red Lake, Minnesota. All Wisconsin reservations operate casinos. Forestry is an important industry. Many people are also part of local off-reservation economies. Unemployment is often around 50 percent.

The Rocky Boy Chippewa-Cree Development Company manages that tribe’s economic resources. The tribe’s beadwork is in high demand. The company organized a propane company and owns a casino as well as recreational facilities. The largest employers on the reservation are the tribal government, Stone Child Community College, and industry. Other activities include cattle grazing, wheat and barley farming, some logging and mining, and recreation/tourism. Unemployment regularly approaches 75 percent.

People in the Montana Allotment Community are integrated into the local economy. Turtle Mountain operates a casino, a manufacturing company, and a shopping center.

Many northern Ojibwas work at seasonal or part-time employment in industries such as construction, logging, and tourism. Fire fighting and tree planting offer some employment possibilities. There has also been an increase in government assistance.

Legal Status The following are federally recognized tribal entities in Michigan: the Bay Mills Indian Community of the Sault Ste. Marie Band of Chippewa Indians, Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa, Keweenaw Bay Indian Community of L’Anse of Chippewa Indians, Keweenaw Bay Indian Community of Lac Vieux Desert of Chippewa Indians, Keweenaw Bay Indian Community of Ontonagon Bands of Chippewa, Sault Ste. Marie Band of Chippewa Indians, and Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe.

The Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians (North Dakota and Montana), as well as some of the "landless Chippewa" in Montana, have been seeking federal recognition since the 1920s. The Christian Pembina Chippewa Indians have also petitioned for federal recognition. Other officially unrecognized communities include the NI-MI-WIN Ojibweys (Minnesota), the Sandy Lake Band of Ojibwe (Minnesota), and the Swan Creek and Black River Chippewa (Montana).

The following are officially recognized northern Ojibwa bands in Ontario: Angling Lake, Bearskin Lake, Big Trout Lake, Caribou Lake, Cat Lake, Deer Lake, Fort Hope, Kasabonika lake, Kingfisher, Martin Falls, Muskrat Dam Lake, Osnaburgh, Sachigo Lake, and Wunnumin. Manitoba bands included Garden Hill, Red Sucker Lake, St. Theresa Point, and Wasagamack. Total population in 1980 was around 10,000.

Lake Winnipeg Salteaux bands in Ontario include Pikangikum, Islington, Grassy Narrows, Shoal Lake No. 39, Shoal Lake No. 40, Northwest Angle No. 33, Northwest Angle No. 37, Dalles, Rat Portage, Whitefish Bay, Eagle Lake, Wabigoon, Wabauskang, Lac Seul, Big Island, Big Grassy, and Sabaskong. Manitoba bands include Little Black River, Bloodvein, Hole River, Brokenhead, Roseau River, Berens River, Fort Alexander, Peguis, Little Grand Rapids, Jackhead, Fairford, Lake St. Martin, and Poplar River. Total population in 1980 was around 19,000.

Daily Life The Michigan Anishinabe retain hunting and gathering rights on some ceded land. The Midewiwin society remains active in most communities, and most tribes maintain an active schedule of traditional or semitraditional events such as powwows, sweat lodges, and conferences. The Bay Mills Community operates its own community college. The Sault Ste. Marie tribe hosts two powwows and publishes a newspaper.

In Minnesota, most people retain their Indian identity in a number of important ways. A community college at Fond du Lac emphasizes tribal culture. People are pursuing several land reacquisition projects and subsistence rights cases. There are a number of powwows and other traditional and semitraditional activities throughout the state. The Ojibwa language, which roughly 30,000 people speak, is taught in schools and colleges. Authors continue a tradition of writing about their culture. Artists and craftspeople continue to produce moccasins, clothing, baskets, and other items. Leech Lake hosts five annual powwows, operates a school and a tribal college, and publishes a newsletter.

Although about half of Wisconsin Anishinabes live in mostly non-native cities and towns, most retain close ties to their home communities. The people maintain their Indian identity through events such as powwows, athletic contests, and traditional subsistence activities. Since a landmark court case in 1983 reaffirmed their subsistence rights on ceded land, the people have redoubled their efforts to defend those rights against a non-native backlash. Toward this end, they have established a number of environmental organizations, such as the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, to manage their natural resources and provide other related enforcement and public relations services.

In 1968, three Anishinabe founded the American Indian Movement (AIM), a self-help organization that proceeded to fight both quietly and openly for Indian rights. Important AIM actions have included the 1969 takeover of Alcatraz Island, the 1972 occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, and the 1973 defense of Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

Northern Ojibwas in Canada have enjoyed decent health care facilities and educational opportunities since the 1950s. Trapping remains important but considerably less so than in the past. Many people live near their relatives. Many people are Christians.

Many Lake Winnipeg Salteaux people in Canada have intermarried with Cree Indians. The native religion has practically disappeared. Christianity, including some fundamentalist sects, has largely taken over, with one result being a high degree of factionalism. Roads have connected the people to the outside world only since the 1950s.