In general, genes are transferred from one generation to the next in a vertical fashion, from parent to progeny through the gametes donated from each parent to form the zygote from which the offspring develops (see Vertical Gene Transfer). In horizontal gene transfer, a gene is transferred from one species to another, often with a virus or bacterium acting as the vehicle (Fig. 1). In vertical gene transfer, the genes must originate in germline cells in order to be transferred. In horizontal gene transfer, the gene may originate in a somatic cell, but the receiving cell must be a germline cell in order for the transferred gene to be passed on to the next generation. Strictly speaking, transfers of genes between somatic cells of two species are not called horizontal gene transfer.

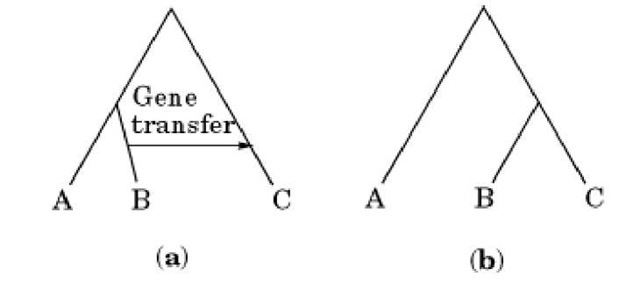

Figure 1. Illustration of horizontal gene transfer and how it affects the (a) species and (b) gene phylogenetic trees.

Horizontal gene transfer is often difficult to detect. It is often suspected, however, when there is marked discontinuity in the phylogenetic tree for a gene, such as the appearance of a gene in one species, but not in any of its most closely related species. Discrepancies between the phylogenetic trees for species and for genes can also indicate that horizontal gene transfer may have occurred.

The nucleotide sequences of entire genomes show that horizontal gene transfers must have occurred often. When the complete genome sequences of three representative species from the three major organismic worlds, namely, Escherichia coli (Eubacterium), Methanococcus jannaschi (Archaebacterium), and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Eukaryote) were compared with each other, approximately 60% of all the genes of the archaebacterial genome are closer to those of the eubacterium than to those of eukaryotes, whereas about 30% of the archaebacterial genes were closer to eukaryotes. The remaining 10% of the genes are archaebacteria-specific (1). Therefore, the archaebacterial genome looks like a mosaic structure, a mixture of genetic material from various genomes. At present, only horizontal gene transfer can explain the mosaic features of the genomes. It implies that a tremendous amount of horizontal gene transfer should have taken place during long-term evolution. Genomes appear to have a robustness that allows major changes in gene order and arrangement without loss of function. This provides an environment in which horizontal gene transfer can occur and provides a source for the emergence of new gene systems and new gene interactions. Thus, the unit of function appears to be the gene, and the positions of genes in the genome have little effect on function. There appear to be only rare examples in which a set of genes must work as a unit. This elasticity of the genome allows it to absorb any disturbances caused by horizontal gene transfer, and it demonstrates the evolutionary significance of the genome itself.