An egg is the female gamete, which is originally haploid and in most cases nonmotile. After fertilization by a sperm, the egg provides the basis for producing a completely new individual. Regarding this subsequent development, eggs belong to the least restricted cell types of the body, as they have the power to produce every other differentiated cell type. Eggs cannot be regarded as nonspecialized cells; instead, they prove to be very specialized cells to accomplish this task.

First, they must mediate sperm-egg interactions. This means that they must be able to induce metabolic pathways in the spermatozoon and biochemical signals from the spermatozoon must be understood, thus leading to intracellular reactions in the egg to promote fertilization. Second, after fertilization with a spermatozoon, the egg needs a machinery to promote biochemical actions that are necessary to fuse the male and female pronuclei. Third, the egg must be able to guide and support the very early cell divisions without, or with only minimum, nuclear control of the developing embryo. Thus, the egg must provide appropriate amounts and species of many different basic elements, such as transfer RNA, ribosomes, and many different proteins, including basic elements like transcription factors. These gene products have been transcribed, and in some cases translated, previously and are stored in the oocyte cytoplasm.

1. Morphology

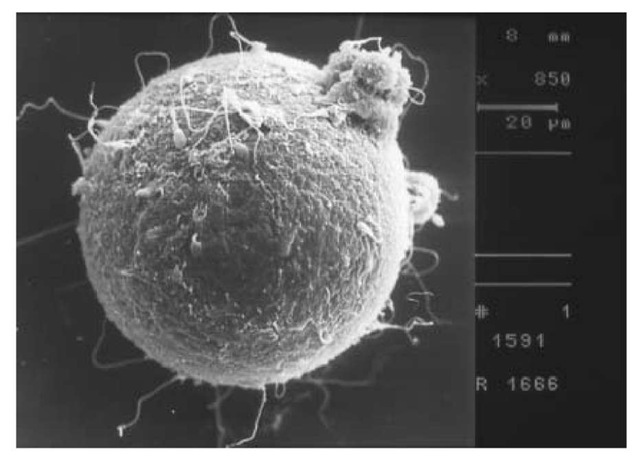

Unlike other cells, eggs consists of an outer porous extracellular matrix, the zona pellucida (1). The zona pellucida is not primarily for mechanical protection of the egg, but its foremost task is to mediate sperm-egg interactions. It is made of long filaments consisting of three types of glycoproteins . In all species thus far investigated, zona pellucida glycoproteins are expressed by the ZPA, ZPB, and ZPC gene family (1). Post-translational modification of the zona pellucida glycoproteins, however, varies with the species. Most of the investigations concern the situation in the mouse. Regardless of their genetic origin, but for functional reasons, the processed glycoproteins are divided into three classes. Murine zona pellucida glycoprotein 1 (ZP1) has a molecular weight of 200 kDa and is assumed to be responsible for the structural integrity of the matrix. Zona pellucida glycoproteins 2 and 3 (ZP2, ZP3) exhibit apparent molecular weights of 99 kDa and 83 kDa, respectively; both act as sperm receptors (2). In the ZP3 receptor, an O-linked oligosaccharide of 3.9 kDa molecular weight plays a central role in recognition and binding of sperm. After induction of the cortical reaction by fertilization, both receptors are converted to their inactive forms, ZP2f and ZP3f, thereby providing a secondary block against polyspermy. In species with extracorporal fertilization, such as sea urchins, the zona pellucida is surrounded by a jelly layer. In mammals, a number of corona cells adhere to the zona pellucida at the time of fertilization.

Between the oocyte plasma membrane and zona pellucida is a region that is termed the perivitelline space. On entrance of a sperm and its fusion with the oocyte plasma membrane, calcium is released from intracellular calcium stores (see Calcium Signaling). As a consequence, the cortical granules are activated and release their proteolytic contents into the perivitelline space, which subsequently diffuse into the zona pellucida. This results in the conversion of ZP2 and ZP3 into their respective inactive forms ZP2f and ZP3f. Calcium release is necessary not only to prevent fertilization from further spermatozoa, but it is also involved in (1) nuclear envelope breakdown, (2) triggering intracellular phosphorylation events, and (3) activation of cell cycle -control proteins leading to mitosis after syngamy.

Figure 1. Electron microscope picture of an oocyte. The oocyte is surrounded by spermatozoa that aim to penetrate the zona pellucida.

Within the oocyte plasma membrane, the egg is filled with cytoplasm that contains basic metabolites necessary for the initial divisions of the cell. Unlike the cortical granules, not all compounds of the cell cytoplasm are located uniformly. This can be seen by light microscopy and has led to a distinction of the egg’s compartments. In the frog, for example, macroscopic partitioning is visible: The nucleus is located at the animal pole, whereas yolk is located at the vegetal pole.

Depending on the species, eggs vary considerably in their sizes and shapes. In mammals, nutrition can be provided during the very early stages of life by diffusion and then by active transport after implantation of the embryo. Therefore, there is no need for substantial nutrition in the egg and, hence, the entire egg is no larger than 0.1 mm. In species in which extracorporal development of the offspring is the rule, the situation is different. The sizes of eggs can range up to a couple of inches, due to large amounts of yolk, as is the case, for example, with birds.