EVERY SUMMER, the residents of Angleton, Texas brace themselves for the possibility that a fearsome hurricane might bear down on their Gulf Coast town near Houston. But nothing could prepare them for the hot and humid July day in 2005 when a different kind of storm hit their quiet town of 18,000 people. The doors of the old gray county courthouse in the town square opened to a flood of television crews who crowded the hallways looking for a place to film. A group of newspaper reporters surged into the main courtroom, squeezing into uncomfortable wooden benches and tapping updates on their laptops to the newsrooms of the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Associated Press, Fortune, and Reuters.

The journalists were in Angleton to cover the news event of the day: the opening statements of a major legal trial that would begin with a Microsoft PowerPoint presentation. Everyone in the courtroom stood when the jurors filed into the room and settled into their seats. The room was silent, here at the eye of the storm, when a man stood up to face the jurors. Little did anyone know that this lawyer was about to unleash a storm of his own from his laptop computer. After all, this was no ordinary PowerPoint presentation he was about to give—it was a Beyond Bullet Points presentation. Like many of the hurricanes that have passed through Texas, this presentation would make headlines for its devastating force.

The lawyer who was about to speak was no stranger to PowerPoint, or to the courtroom. Born and raised in Texas, Mark Lanier specializes in representing plaintiffs in personal injury trials and has a long string of winning verdicts for his clients. Early on, he worked as a lawyer in large law firms, but later he started his own firm and eventually moved it to the outskirts of Houston. Mark would soon demonstrate that these days anyone with a laptop computer and PowerPoint software—and an effective strategy for using them— can make as great an impact as a person with unlimited resources.

Mark turned to his client, the plaintiff in this case, who was sitting in the first row with her family. "Your Honor," Mark said, "if I may begin by introducing to the jury and to the Court my client." As Carol Ernst stood, Mark introduced her and her daughter. Carol’s husband, Bob, had died of a heart attack, and she suspected that a painkiller her husband had taken, Vioxx, was a cause of the heart attack. So she filed a lawsuit against the defendant, the drug’s manufacturer, Merck & Co., Inc. Mark would represent Carol throughout the trial.

As Carol sat down, Mark walked toward the jury box past the row of lawyers sitting at the defense table. These lawyers were from two internationally recognized law firms hired by the defendant. With billions of dollars in their war chest, the company could afford the best. Facing such a formidable opponent with deep pockets, Mark knew he would need to be at the top of his game and use the tools and techniques he had to the best of his ability to make the greatest impact.

Mark paused at the jury box and made eye contact with each of the 12 jurors. Before the jurors arrived, Mark had wheeled the lawyers’ podium to the side of the courtroom because he didn’t want a piece of furniture, or anything else, to stand between him and his audience. Mark had a folksy style when he talked to jurors in the courtroom, speaking with a Texas drawl, in colorful language, and in a conversational manner. But by now, Mark’s legal opponents knew that to interpret his simple style as unsophisticated would be a big and expensive mistake, because of his strong track record of successful verdicts in jury trials.

The judge had instructed the jurors earlier that when they took their oath, they had become court officials like himself and the lawyers. The jurors were charged with administering justice in this case, by listening to all the evidence in open court and then making a decision based on the facts and the judge’s instructions and reading of the law. Like any audience, they sat ready to hear what the presenter would say.

know your audience

You need to know your audience well before you start planning your presentations. Mark knew some things about his audience in the jury box— the legal teams from both sides had prepared a written questionnaire for the jurors, in which they found that the jurors were in their 20s and 40s, high-school educated, and from a range of professions, including an electrician, a college student, a construction worker, a product technician, a homemaker, a secretary, and a government employee. The lawyers also had an opportunity to ask jurors questions in person during a Q&A session called voir dire. In your own presentations, the better you know your audience, the better you’ll be able to customize your material to them.

As you might be able to relate to, most experienced speakers say they get nervous before a big presentation. Likewise, Mark must have felt some nervousness, but not just because the jurors were watching him closely. Plaintiffs’ attorneys like Mark can spend upward of $1 million to bring a case to trial on behalf of their clients, and if they lose, they literally have lost everything they put into the case. The defendant had a great deal to lose as well, because this was the first case to go to trial against the pharmaceutical company. Beyond any negative media coverage the case might bring to the company, a verdict against the company could have a big impact on its bottom line—it could lose millions of dollars in an unfavorable verdict, and possibly lose billions of dollars in market value if its stock price dropped on the news.

Based on what the plaintiff and defendant had at stake in this trial, the courtroom presentation was about as high-stakes as a PowerPoint presentation can get.

Stepping onto the Media stage

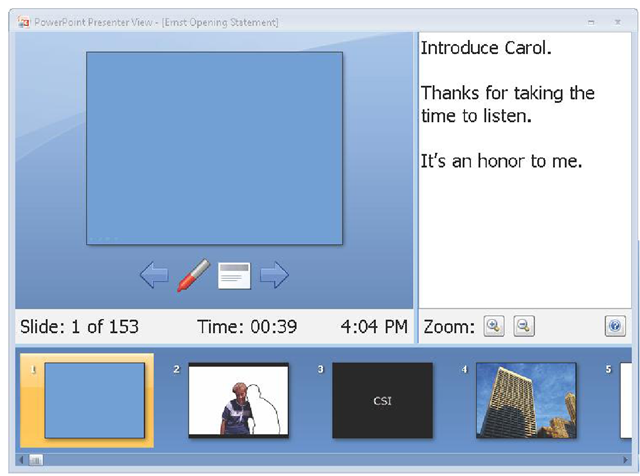

Mark glanced down at his laptop computer, which sat facing him on a small table below the jury box, out of sight of the jurors. What he saw on his laptop screen was a feature in PowerPoint called Presenter view, similar to the screen shown in Figure 1-1, which gave Mark a special view of the presentation that only he could see. Like the teleprompter that broadcasters use to present their speaking notes, this sometimes-overlooked PowerPoint feature gives you the ability to see additional information that does not appear on the screen the audience sees. For example, at the upper left of his screen, Mark could see the blank blue slide that the jurors were currently looking at. And he also could see his speaker notes at the upper right, reminding him of the points he planned to make while each slide was displayed on screen, as well as a row of small previews of his upcoming slides at the bottom of the screen, helping him to make a smooth transition from one slide to the next.

FIGURE 1-1 A feature in PowerPoint called Presenter view gave Mark a view of the current slide the jurors saw on screen, along with his own speaker notes and thumbnail views of upcoming slides.

As he began speaking, Mark’s thumb pressed the button on a remote control device like the one shown in Figure 1-2, which he cupped in his hand at his side where the audience would not notice it. This remote would be his constant companion for the next couple of hours, as he used it to advance the PowerPoint slides while he spoke, giving him flexibility to slow down or speed up to match his narration and ensure that the experience appeared seamless to the jurors.

FIGURE 1-2 Remote control devices offer presenters the ability to advance the slides of a PowerPoint presentation without using the keyboard.

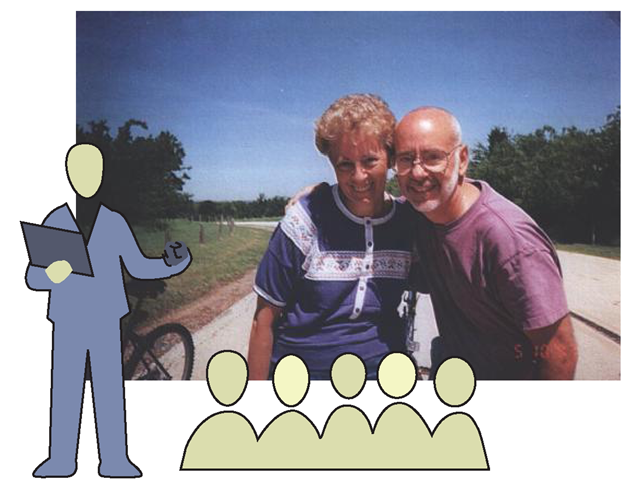

"It’s extremely important to me that you hear what this case is about," Mark said. "So I’ve put together…different exhibits to try and help it stick in your brain and help you focus on what we think are critical points." When Mark clicked the remote control button, it signaled his laptop computer to advance to the first image in the PowerPoint presentation. Although the jurors could not see the laptop below the jury box, they did see an image of Carol and Bob appear on the 10-foot screen directly behind Mark, as illustrated in Figure 1-3. From where the jurors sat, it appeared that Mark was in a giant television set, as the images on the screen would soon start dissolving and changing behind him in a seamlessly choreographed media experience.

FIGURE 1-3 The images from Mark’s PowerPoint presentation filled the 10-foot screen behind him.

The projected colors, images, and words were so thoroughly integrated into the presentation experience that turning off the projector would have been like eliminating the set of a theater production or the screen in a movie theater. Never breaking eye contact with the jurors or looking back at the screen, Mark now began to tell a gripping story that would lay out the evidence of the plaintiff’s case through the next two and a half hours of the presentation.

A Singular Story

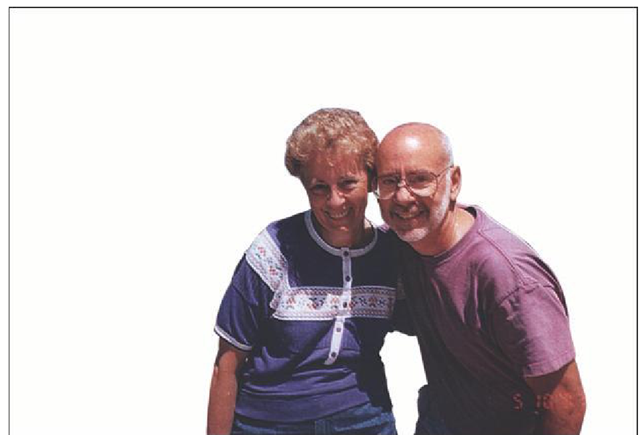

What was notable about Mark’s PowerPoint slide, shown on its own in Figure 1-4, was not so much what was on it, but rather what was not on it. You would probably expect the slides of a PowerPoint presentation to be filled with bullet points, but here the jurors saw only the visual power of a single, simple photograph. Such full-screen images are rare in PowerPoint presentations, but this image fit in perfectly with what Mark would do next.

FIGURE 1-4 A family photo of Bob and Carol showed the happy couple after they were married.

With a photograph of the couple on the screen as his backdrop, Mark began telling an anecdote to introduce Bob and Carol to the jurors. "But let me tell you a little bit about Bob," Mark said. "Bob was a great fellow who always took [Carol] to wonderful, interesting places. They went to the kite festival in Washington State. They went to the balloon launch in Albuquerque. They had a lot of fun. He got her into tandem bike racing. They weren’t the winning kind of athletes. They just did it to be together, and it was a good, fun way for them to live together."

Mark knew that telling the details of an anecdote like this one about Carol and Bob is an effective way to introduce a new and complicated topic to an audience. With a simple story of a bike race, the jurors could quickly imagine what Carol and Bob’s relationship and lives were like. And seeing the family photograph would make it easier for jurors to relate to the plaintiff, perhaps reminding the jurors of similar photos they have taken or seen in their own families. The photo and specific details of the couple’s life together would work powerfully to quickly introduce Carol and Bob to the jury and make an emotional connection with them. This slide worked much more effectively than a list of bullet points ever could, because we don’t live our lives in bullet points—we live in images and stories.

"They did get married after being together for a number of years," Mark explained. "Interestingly enough, they were introduced over exercise. And you’ll hear Carol talk about her…daughter…being the matchmaker between Carol and Bob." Here Mark added a detail informing the jurors that they would hear from Carol herself on the stand, establishing a sense of anticipation that they would get to hear from her firsthand. Mark knew that hinting at events to come is an effective way to grab any audience’s interest. And by using the specific details about Carol and Bob while the photograph was displayed on screen, he connected the audience’s emotions to the image.

Mark clicked the remote control again and displayed the same photograph, except now the background behind the photograph had disappeared, as shown in Figure 1-5. As the new photograph appeared, Mark said, "They had a wonderful time together. But ultimately…the picture starts to fade and things start to go different. And let me tell you why." People are not used to seeing family photographs where the background suddenly disappears, so this visually set the stage that something unexpected was about to happen to Carol and Bob. The emotions of the audience that Mark had associated with the photograph suddenly were stripped away.

FIGURE 1-5 The next slide shows the same photograph with the background stripped away to indicate that something unexpected had happened.

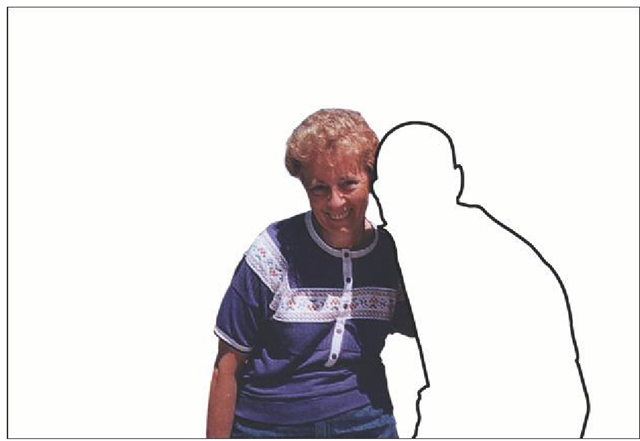

Clicking again, Mark displayed a new version of the photograph, except in this one, Bob was missing from the photograph. In his place was a thick black line like the chalk outline from a crime scene, as shown in Figure 1-6. "You see, Bob Ernst is dead today," Mark said. "One of my witnesses that I want to bring in the case I cannot bring you. Bob Ernst cannot come in here today. He is no longer here. He didn’t know he was going to need to be here. He didn’t leave us anything in video. He didn’t leave us anything in writing that would talk about the issues that we need to talk about."

This striking photograph visually communicated to the jurors that the worst had happened—that Bob and Carol’s happiness ended abruptly and unexpectedly when Bob died of a heart attack. The black outline around where Bob had been in the photo visually brought home the point that Bob’s death suddenly had left a hole in Carol’s life, and in her heart.

FIGURE 1-6 This slide shows Bob missing from the photograph, with only a thick black line to indicate where he once was.

Mark knew that his audience came from a part of Texas that was growing increasingly conservative and that the jurors might not be predisposed to award a big verdict to a plaintiff in a product liability case like this. But with the thick black outline that indicated where Bob had been, Mark also introduced a powerful new outline for his presentation. If the jurors were not going to be friendly toward a product liability case, Mark was now visually reframing his opening statement to a new story line that the conservative jurors would find more engaging—a murder mystery. In this third photograph, the black outline subtly communicated a familiar story setting that the jurors immediately would understand—a crime scene from a television show. This unexpected use of a familiar convention from TV would surprise the jurors and make the idea stick in their minds. This slide would then thematically transition to the next, pivotal, slide in the presentation.

Mark clicked the remote again, and this time a black slide appeared with the phrase CSI: Angleton on it, similar to the slide shown in Figure 1-7, as he said, "If we were going to put it into a TV show, this would be ‘CSI: Angleton.’ …What you’re going to do is… follow the evidence, like any good detective would."

FIGURE 1-7 Next the words "CSI: Angleton" appeared on the screen as Mark told jurors that they would be like crime scene investigators, sorting through the evidence to figure out what caused Bob’s death.

In an entertaining fictional story, the main character is someone an audience observes from a distance. But in a nonfiction presentation, making the audience the center of the action can dramatically increase their sense of involvement.

In keeping with classical storytelling form, Mark’s next step would be to present the main characters with a problem they would have to face.