An Effective Screen and Handout

By viewing your slides in Notes Page view like the frames in a filmstrip, you align your approach with the dual channels—the information that is presented to the visual channel is in the on-screen slide area, and the information presented to the verbal channel is in the off-screen text box. This approach also creates a well-balanced handout that you print in Notes Page format, as shown in Figure 2-14. By using PowerPoint this way, you ensure that you produce both an effective live presentation and an effective printed document.

It is no accident that the structure of a filmstrip is conspicuously similar to the dualchannels concept. When you watch a film with sound, your mind coordinates the different information from the soundtrack and the visual frames on screen.

For almost a century, filmmakers have managed to communicate complex ideas to audiences around the world with synchronized images and sound, with little if any text on the screen. Likewise, working memory can easily coordinate visual and verbal channels if they are properly coordinated and presented.

With the screen behind the speaker, the audience sees and quickly digests the slide and then pays attention to the speaker and his or her verbal explanation. The entire experience appears seamless to the audience.

Using the off-screen notes area in Notes Page view also takes into account the fact that the speaker has a voice during a presentation, which offers a critical source of information that has to be planned and integrated into the experience.

BBP fundamentally changes the media model for PowerPoint from paper to a filmstrip. But the difference between a filmstrip and the BBP approach is pacing. In film and television, you commonly view 24 to 60 frames per second. A BBP presentation runs at the speed of conversation—about one frame per 30-60 seconds—allowing time for the audience to digest the new information and then focus next on the presenter. This even and appropriate pacing ensures that your audience experiences only the right things at the right times.

The old Way Addresses only one Channel

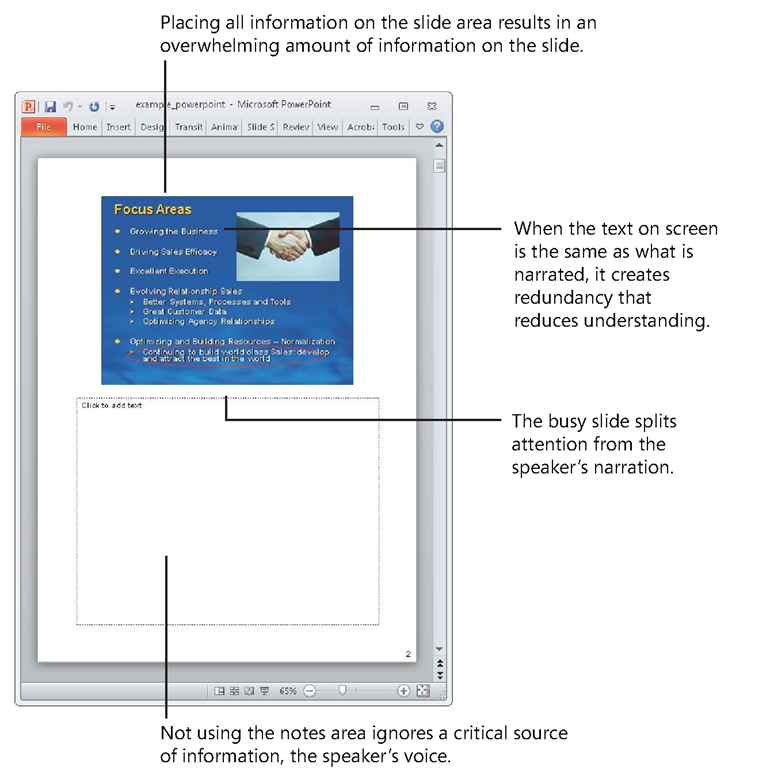

If you choose not to address both the visual and verbal channels, you see from the Notes Page view of a conventional slide shown in Figure 2-15 that you load up the slide area at the top with all of the information you want to communicate both visually and verbally. Because half of the available real estate available for information in Notes Page view is not used—the off-screen text box below is empty—the slide area becomes the single place to hold both spoken words and projected images.

FIGURE 2-15 The conventional PowerPoint approach does not incorporate the dual-channels concept and instead places both visual and verbal information in the slide area.

When you do not align your PowerPoint approach with the dual-channels concept, you impair learning in a number of ways. For example, ignoring the off-screen text box creates a scarcity of resources in the slide area, which predictably produces overloaded slides. Words will usually take priority over visuals, so you will tend to see slides filled with text.

Visuals added to these already crowded slides are usually reduced to the size of postage stamps so they can be squeezed between the boxes of text. These dynamics produce slides that are overly complex and difficult to understand.

When this type of slide is displayed during a presentation, the audience tries to make sense of the overloaded slide instead of paying attention to the speaker. When they do shift attention to the speaker, they soon look back at the slide and work hard to try to synchronize the two sources of information. Researchers call this the split-attention effect, which creates excess cognitive load and reduces the effectiveness of learning. You can observe similar dynamics when you’re watching a film or TV show and the sound is slightly out of sync—it’s very noticeable because your working memory has to do the extra work of continually trying to synchronize the mismatched images and narration.

Myth VS. Truth

Myth: I don’t need to worry if what I say doesn’t match up with my slide.

Truth: Research shows that people understand a multimedia presentation better when they do not have to split their attention between, and mentally integrate, multiple sources of information.

Another problem with ignoring the off-screen text box in Notes Page view is that you do not recognize and plan for a primary source of information during PowerPoint presentations—your own voice. The result is that the relationship between your spoken words and projected visuals is not fully addressed. You might assume that the information on your slide can stand alone, without verbal explanation, but a PowerPoint slide does not exist in a vacuum—you are standing there speaking to your audience while you project the slide.

You must effectively plan how your spoken words and projected images relate to each other. And if you write nothing in the off-screen notes area, you will be unable to take advantage of Presenter view.

FIGURE 2-16 If you don’t write out what you will say in the notes area in Notes Page view, there’s little point in using Presenter view, because nothing will appear in the speaker notes pane and the text on the slides is too small to read on the slide thumbnails.

Audiences might not know about dual-channels theory, but they do know how they feel when presenters don’t integrate the concept into their PowerPoint approach. When presenters read bulleted text from the screen, audiences complain that the presenter should "E-mail it to me!" or "Just give me the handout!" This frustration has a research basis—writing out the text of your presentation on your slides and then reading it to your audience contradicts the widely accepted theory of dual channels.

You might assume that presenting the same information in multiple ways will reinforce your point. But if you present the same information to the two channels, you reduce the capacity of working memory and in turn reduce learning by creating what researchers call the redundancy effect.

When someone speaks, you process the verbal information at one speed. When the speaker also displays the text of the speech, you process the same information at a different speed—your mind first takes in the text visually and then verbalizes it for processing in the verbal channel.

Because the same information is arriving through the same channel at different speeds, working memory has to split attention between the two sources of information as it works hard to reconcile them. This redundancy quickly overloads working memory and impairs learning.

An Ineffective Screen and Handout

By addressing only one channel in your presentation, as shown earlier in Figure 2-15, you create both split attention and redundancy in a live presentation. And by not capturing what is said verbally in the off-screen notes area, you also miss the chance to use PowerPoint to create an effective handout by printing the slides in notes page format.

Redundancy also happens when the same information is presented both visually and in text because the same information is entering through two channels and the mind has to exert more effort to reconcile them. This reduces the efficiency of working memory and can lead to the cognitive overload that so frustrates audiences.

Myth VS. Truth

Myth: It’s OK to read my bullet points from the screen.

Truth: Research shows that people understand a multimedia presentation better when the words are presented as verbal narration alone, instead of both verbally and as on-screen text.

To explore the redundancy effect, Mayer conducted experiments using two multimedia presentations. The first presentation included the same material both narrated and displayed with text on the screen, and the second presentation included the narration with the text on the screen removed. Audiences who experienced the second presentation retained 28 percent more information and were able to apply 79 percent more creative solutions using the information than those who experienced the first presentation.

Thus, the dual-channels concept turns one of our core assumptions about PowerPoint upside-down. Contrary to conventional wisdom and common practice, reading bullet points from a screen actually hurts learning rather than helps it. Research shows that when you subtract the redundant text from the screen that you are narrating, you improve learning.

If you choose not to align your PowerPoint approach with dual channels, you diminish the potential effectiveness of your presentations. When you place both verbal and visual material in the slide area, the busy slide splits the audience’s attention between screen and presenter, which creates additional load on working memory. And when you present the same information in both visual and verbal form, you create redundancy that overloads working memory. You resolve the situation in BBP by effectively coordinating visual and verbal information in Notes Page view.

Realignment 3: Use Normal View to Guide Attention on the Screen

Now that you’ve realigned Notes Page view with the research, it’s time to get back to normal in terms of the way you’re used to working in PowerPoint. Click the View tab, and in the Presentation Views group, click Normal to display Normal view, as shown in Figure 2-17. The third trick of BBP is to always work in Normal view last.

FIGURE 2-17 The most common way to work in PowerPoint is in Normal view.

Research Reality 3: You Have to Guide Attention

The third research reality confronts the PowerPoint assumption that you create your slides however you want and your audience will understand them. In the pipeline metaphor, a presentation exists by itself, independent of the people who receive it—a presenter simply pours information into the passive minds of the audience.

Yet researchers have long known that the mind is not a passive vessel, but rather it is an active participant in the process of learning. It is the minds of your audience that have to create understanding out of the new information they process in working memory.

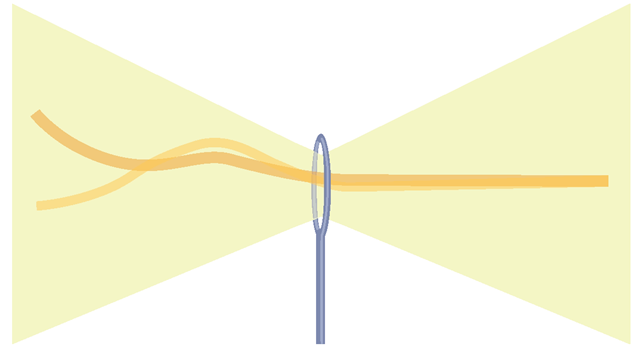

You play an important role in helping your audience create understanding by designing slides in specific ways that guide the attention of working memory to the most important visual and verbal information, as illustrated in Figure 2-18.

FIGURE 2-18 The third research reality is that you must guide the attention of working memory.