Can I Apply a Story Structure to an "Informational" Presentation?

One objection to using Beyond Bullet Points (BBP) is the misconception that a story structure is not appropriate for informational presentations.The research reality is that people need to actively engage new information, so offering them tools and techniques to do so will help them learn better. Why pass up the opportunity to engage your audience when doing so can increase focus and involvement? The Act I technique of creating dramatic tension by creating a gap between the Point A and Point B headlines is thousands of years old and offers a dynamism that still works today when it is applied to any type of presentation.

The problem created by the gap between the Point A and Point B headlines also forms the purpose of your presentation, so when you make the problem clear, you make your purpose clear. This problem is central to your entire presentation and forms the singular question that your presentation will try to answer. It creates an emotional center of gravity that focuses your story and makes it cohere across all of its separate parts.

The gap between Points A and B defines the problem that you are there to help your audience solve and also answers for the audience another important question: "What’s in this for me?"

Whatever way you frame the gap between Points A and B is how you frame the entire presentation going forward. If you get this framing right, your presentation will create a connection with your audience; if you get it wrong, you will create a disconnect. Defining the problem for your audience is probably the hardest thing you’ll do in your presentation. You and your team might go through several rounds of drafts and revisions to get the Point A and Point B headlines right, but when you do, the rest of your presentation will fall into place.

When you have a clear problem established with the Point A and Point B headlines, it’s time to let your audience know how you propose to solve it.

Focusing the Audience with the "Call to Action" Headline

Remember, the Point A headline defines a challenge, and the Point B headline shows your audience where they want to be in light of that challenge. Now you’ll literally fill the gap between A and B with your Call to Action headline.

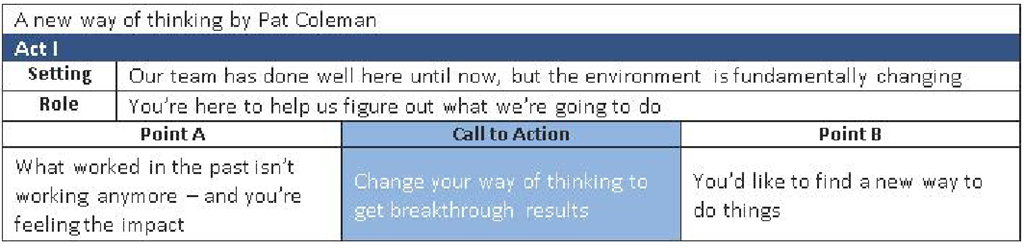

The Call to Action headline defines the reason you’re the presenter—you’ve taken the time to figure out how the main character can solve the problem at hand. To complete the fifth slide, in the dark gray cell labeled Call to Action, type an answer to the question your audience is wondering: "How do I get from A to B?" In this case, enter Change your way of thinking to get breakthrough results, as shown in Figure 4-13.

FIGURE 4-13 Write your fifth headline of Act I to describe the call to action.

In this example, you ask the executives to "Change your way of thinking to get breakthrough results" to close the gap formed by the Point A and Point B headlines.

In the context of the first five slides, the audience now affirms a problem they face, and they will be able to solve it if they let you help them in the story that will continue shortly.

Although the phrase "change your way of thinking" may be more direct than you want to be with this particular audience, it does strip down to the essence what you want from them in clear and direct language. If less-direct phrasing is in order, modify the wording to meet your and your audience’s needs. In this example, other options include: "Consider a new way of thinking," "Explore new ways to think," or "Uncover new ways to think." Whatever wording you choose, it should be a good fit for both you and your audience.

The Call to Action Headline

The Call to Action headline answers the question your audience is wondering: "How do I get from A to B?"

The Call to Action headline should describe what your audience should do or believe to solve the problem created by the gap between the Point A and Point B headlines—it is literally the point of the presentation. Your final wording is important, because the Call to Action headline clearly defines what you and your audience want to accomplish and offers a clear direction and road map that they will be able to use and follow through the rest of the presentation.

The Call to Action headline also puts your ideas in a decision-making format that’s important to people who want to accomplish something. In a single sentence, the wording of the Call to Action headline defines how you know if you were successful in your presentation, whether that success is a next meeting, a sale, an agreement, or a good grade. If your audience accepts your Call to Action headline by the end of your story, you’ll know you succeeded.

I’M STUCK!

What do you do if you get stuck somewhere in the process of writing the headlines for your first five slides?Often the process of working through the structure in Act II will help you define and refine Act I.

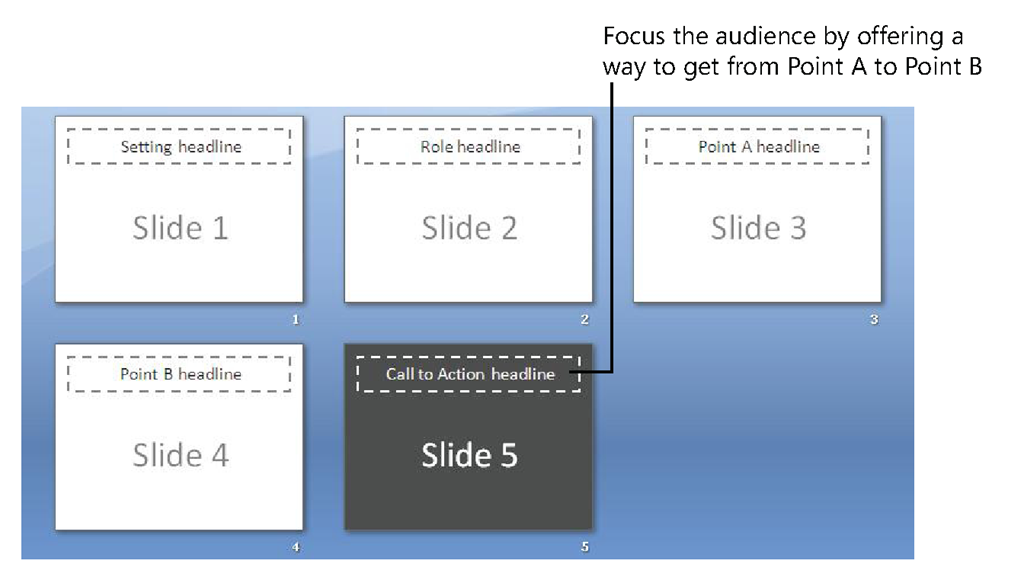

When you’ve written the Call to Action headline in Act I of the story template, you’ve made sure that you will focus the audience by offering them a way to get from Point A to Point B in the fifth slide of your presentation, as shown in Figure 4-14. The Call to Action slide in this illustration now has a dark gray background like the corresponding cell in the story template, making it stand out from the others because it is in fact the most important slide in a presentation. If you had only one slide to show, it would be the Call to Action slide.

FIGURE 4-14 The Call to Action headline focuses Act I and the rest of the story to come.

Choosing a Pattern to Follow

Now that you have chosen a story thread to help new information pass through the eye of the needle, you increase the efficiency of working memory by introducing a pattern for the story to follow. Do this by adding a motif, or recurring theme, to the first five slides. A motif carries your ideas all the way through your story in a coherent way and adds color and interest to your language. It also makes the job of searching for graphics to add to your slides significantly easier because you map the motif to your visuals.

A motif might seem like a "nice-to-have" addition to make the presentation colorful and interesting, but research shows that it can provide much more than just a pretty face for your presentation. Working memory cannot possibly process all of the new information it experiences, and without a clear structure to organize the new information, it has to create a structure from scratch—a very inefficient process.

But with a structure that works, you help working memory select, organize, and integrate the new information much more effectively. The structures that happen to work best are ones the audience already holds in long-term memory—they might take the form of a familiar metaphor, an organizing system like 1-2-3, or any number of familiar story themes.

For more information about metaphor and its impact on the way people think, see George Lakoff’s work, including Metaphors We Live By, 2nd ed. (with Mark Johnson; University of Chicago Press, 2002).

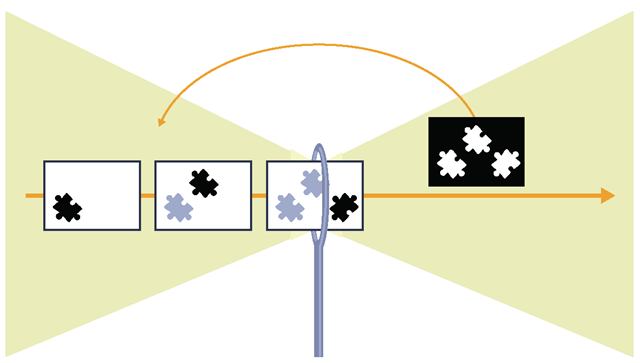

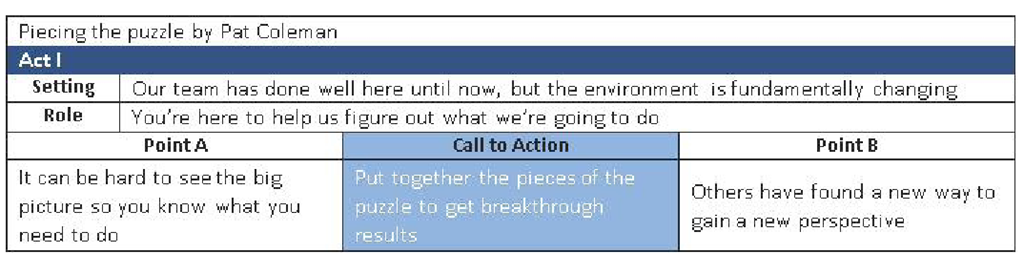

For example, most people are familiar with the process of putting together a puzzle, so a puzzle-making structure already exists in their long-term memory. When you apply a puzzle motif to the structure of your story, as shown in Figure 4-15, you increase the efficiency of working memory of your audience so that they can much more quickly make sense of the new information. Introducing a preexisting structure reduces cognitive load because working memory doesn’t need to exert as much energy to create a structure from scratch.

FIGURE 4-15 When you pull a familiar structure from long-term memory and use it to structure a presentation, you make working memory more efficient.

There are many different motifs you are able to apply to your presentation, which are incorporated into some of the example phrases.To apply a motif to your presentation, integrate it through your headlines as in the following variations of the Act I example in this topic. Keep the following general principles in mind when you search for a motif for Act I:

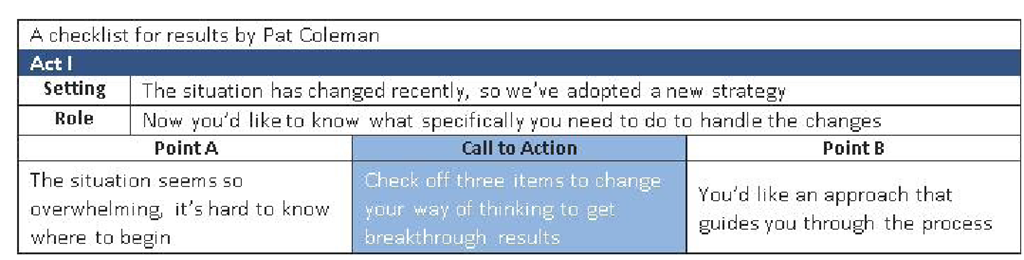

■ The motif should exist already in your audience’s long-term memory. You need to get into the minds of your audience to find the right motif, because the structure has to exist already in their long-term memories. You need to figure out what they think, and what they know, through your research, interviews, and analysis. In legal trials, lawyers create juror questionnaires designed to find out what potential themes might resonate in a legal presentation. You might need to do similar in-depth research if your presentation is particularly important. If you don’t know your audience or can’t find enough information about them, choose a general metaphor like the checklist motif shown in Figure 4-16.

FIGURE 4-16 The checklist motif is familiar to most audiences.

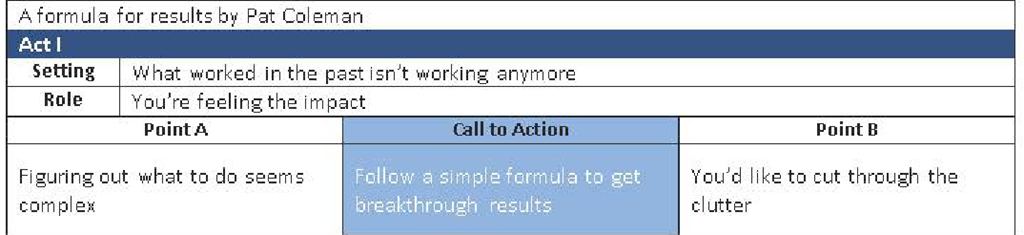

■ The motif should resonate with your audience. Your motif needs to be a good match with your audience, and they should be able to easily relate to it. A motif can work against you if the structure is a mismatch, because it distracts your audience or misleads them into thinking you’re not serious. The motif should also resonate with you as the presenter—choose one that you personally can relate to so that it draws out your personality and warmth and brings your ideas to life with your natural enthusiasm. Only use a complex or special motif if everyone in your audience shares knowledge of it, as in the formula example shown in Figure 4-17.

FIGURE 4-17 The formula motif can resonate with those who deal with numbers.

■ The motif has to be simple. When you find a motif, simplify it and break it into its essential elements before you apply it to your first five slides. For example, you need a more specific motif than just the general topic of puzzles, so focus the motif by using the phrase "put together the pieces of the puzzle," as in the example shown in Figure 4-18. The motif should be clear and easy to understand, and it should couch and complement your ideas without becoming convoluted or clichéd or making things confusing.

FIGURE 4-18 The puzzle motif is simple yet effective.

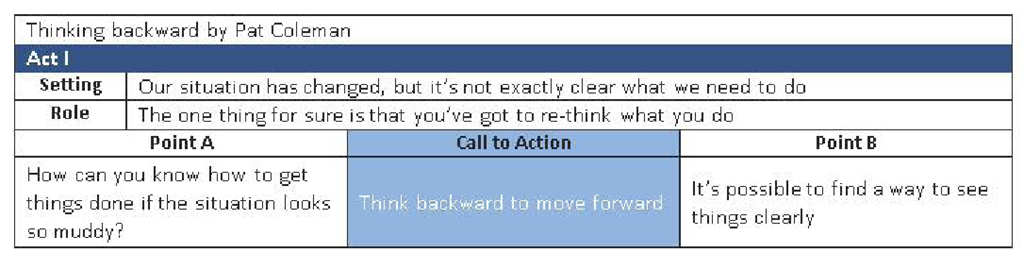

■ A motif is more memorable if it is unexpected. Introducing a surprising motif in Act I will also increase memorability. Choose a surprising insight, a different way of looking at things, or another unexpected way to introduce your idea, as shown in Figure 4-19. Creatively applying a motif by putting it in a surprising context can heighten interest and stimulate creative thinking and mental participation. The more surprising and interesting and engaging the motif is, the more memorable it will be. But as mentioned earlier, make sure that in every case the motif is a good match with your audience.

FIGURE 4-19 Telling someone to go backward instead of forward gives a twist to a journey motif.