Discussion

Asian OSA Prevalence

There is little information of the prevalence and severity of OSA in Asian snorers although OSA may not be uncommon in Asian patients. There is no information on snoring and OSA in Asian population either. Nevertheless, there is a single report on Singapore population, which is predominantly Chinese (Puvanendran et al , 1999).The authors contend that the sleep apnea syndrome is more common than the 2-4% prevalence frequently quoted (Young et al., 1993). The authors studied the snorers in an adult population in Singapore and then went ahead to evaluate how many snorers suffer from pathological apnea as well as sleep apnea syndrome. Their examinees age ranged from 30-60 years. There were 106 consecutive habitual loud snorers of a similar age group in the same population studied with PSG in their sleep laboratory. In that laboratory, an AHI greater than 5 was regarded as pathological. The authors have found that 24.09% were loud habitual snorers. Among the latter, 87.5% of loud habitual snorers had significant OSA on PSG and 72% of these apneics complained of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS). Assuming the clinical observation that all apneics snored, and by extrapolating these figures, the authors conjecture that sleep apnea syndrome affects about 15% of the population. EDS in their cases were validated with clinical hypersomnia. Hypersomnolence was significantly related to the poor delta wave sleep. OSA occurred mainly in stage 1 and 2 non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep instead of in REM sleep. Frequently, the arousals prevented sleep from going beyond stage 1 and 2. With such a higher-than-expected prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome in Singaporean population aged 30-60 years is likely because of the evidence that the people in that population, aged 30 to 60 years, suffer more hypersomnolence, which is associated with the repression of delta wave sleep by apnea occurring taking place mostly in stage 1 and 2 NREM sleep. (Puvanendran et al, 1999)

Conversely, the reported prevalence of OSA reveals as follows. The 19% of 1,775 subjects with a mean age 71 years, SD 10.5, range 40-100 had OSAH (obstructive sleep apnea-hypoxia) (Gottlieb DJ, 2004). In the Philippine and Taiwan, there is a lack of the above studies.

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is defined as having AHI score of 5 or higher, it was 9 percent for women and 24 percent for men. Male sex and obesity were strongly associated with the presence of sleep-disordered breathing, according to a US study (Young et al, 1993). In the U.S., a high percentage of over-65 years subjects have AHI>5; this is the population norm. All elders do not need to be treated if their AHIs are greater than 5. An AHI >=5 has conventionally been a cutoff for the presence of SDB. A higher cut-off of AHI >15 has been used, especially for the elderly, in most of sleep studies. An AHI >20 might be better to distinguish those requiring treatment. There are not enough prospective studies to indicate any treatment responses at different levels of AHI. It is unclear that AHI is a risk factor for those aged over 65 years. A report in English by Ancoli-Israel et al presented that (Ancoli-Israel, 1996) it was largely central apnea, NOT obstructive apnea. Hence, central apnea predicts mortality above age 65 years; others also published similar data (Lavie et al, 2005; Tang, 2007). Nevertheless, to the interest of researchers, Asian’s small upper airway merits attention. With respect to the risk factors for SDB, for example, a report from Singapore indicated that the risk factors associated with habitual snoring and SDB were largely similar to those reported in other populations (Puvanendran, 1999). However, differential risks may underscore the importance of ethnicity in determining the burden of SDB. It is mandatory for health care development and research on SDB in Asia and the answer will come with hard work towards endorsement of alertness of this circumstance in both lay professional communities (Lam et al, 2007).

Snoring is an independent and significant risk factor for a vascular disease especially for stroke and myocardial infarction. It is not uncommon that patients in Sleep Studies are not aware of their own snoring, which was consistent with the original indication of sleep-problem referrals to one of the Taiwanese studied population that patients were not referred solely for sleep apnea, or for snoring alone. For all practical purpose, they were referred rather for mixed sleep problems in most of Sleep Medicine Laboratories. Many patients are not aware of their own heavy snoring and nocturnal arousals. Any excessive and inappropriate assumption that subjects who did not give an account of snoring and sleepiness were lacking OSA is almost definitely erroneous. We should always be ready to lend a hand by questioning the bedroom partner of a potential patient with chronic sleepiness and fatigue, or other type of sleep disturbances.

Table 3. Comparison of descriptive Data (Basic Parameters) between two societies’ studies

|

Setting |

The Philippine |

|

Taiwan |

|

||||

|

|

N=78 |

|

N=223 |

|

p value |

N=21 |

N=103 |

p value |

|

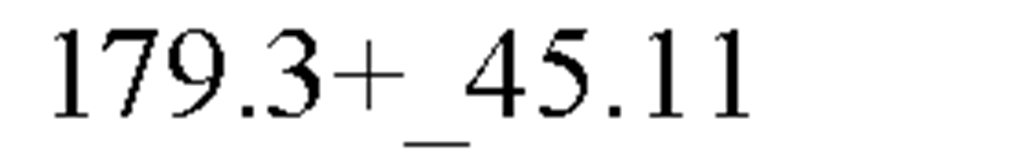

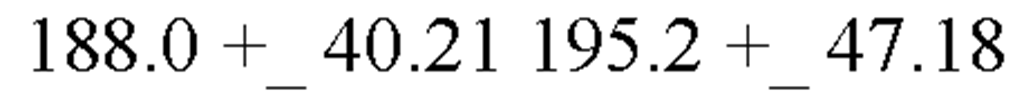

Age, yr |

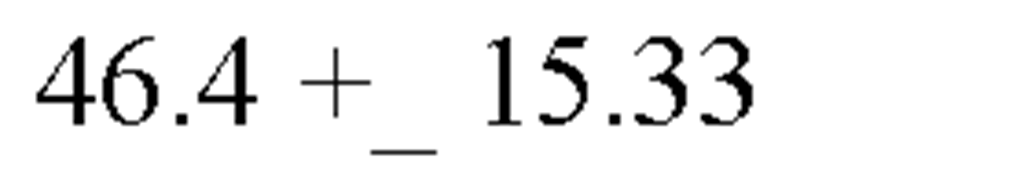

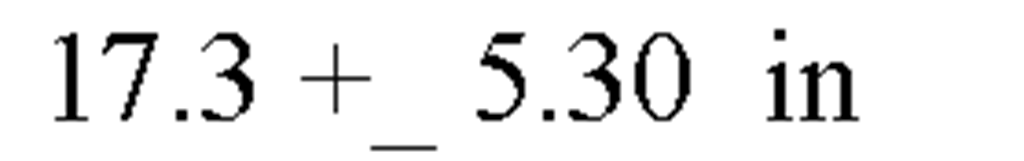

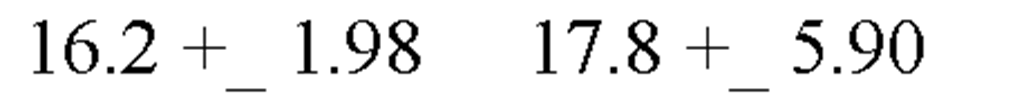

46.4 +_ |

15.35 |

47.8 + |

_ 12.11 |

NS |

700.66+-3.89 |

72.1+-4.98 |

NS |

|

Gender (F/M) |

35/43 (45/55) |

28/195 |

(13/87) |

NS |

14/7 |

32/71 |

NS |

|

|

Height, cm |

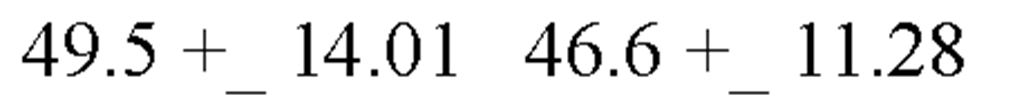

163.9+ |

_ 9.42 |

169.5 + |

_ 7.61 |

0.002* |

155.95+-6.73 |

160.54+-7.68 |

0.15 |

|

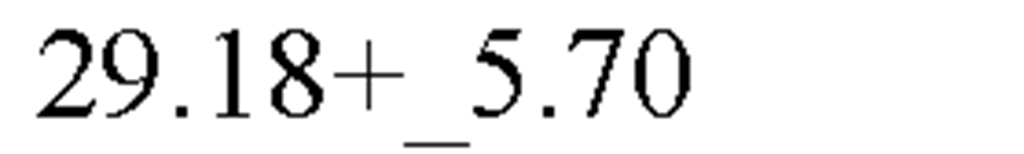

Weight, kg |

156.8+ |

50.60 |

190.5 + |

_ 46.31 |

0.002* |

58.58+-7.40 |

67.01+-12.17 |

0.003* |

|

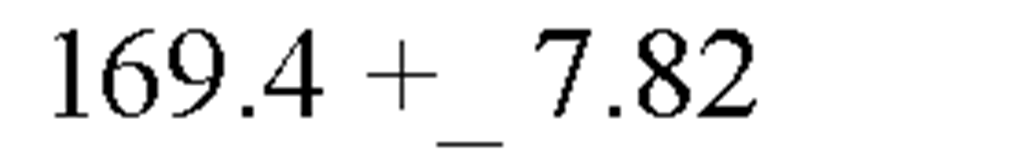

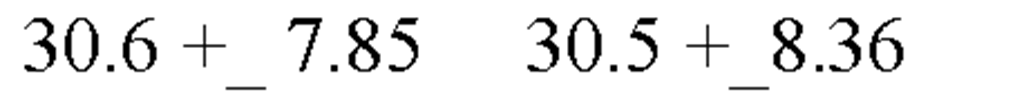

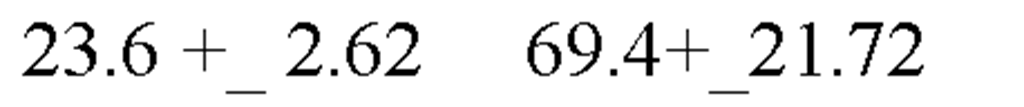

BMI, kg/m2 |

25.9 +_ |

6.36 |

30.2+_ |

7.72 |

0.001* |

24.01+-2.89 |

26.03+-4.69 |

0.069 |

|

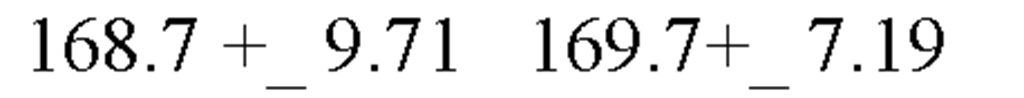

Neck size, cm |

15.5 +_ |

2.13 |

17.5 + |

5.48 |

0.004* |

34.56+-2.82 |

37.20+-3.30 |

0.001* |

|

Obstructive sleep apnea |

None |

Yes |

NS |

None |

Yes |

NS |

||

|

AHI |

<5, |

>=5 |

<5, |

<=5 |

||||

|

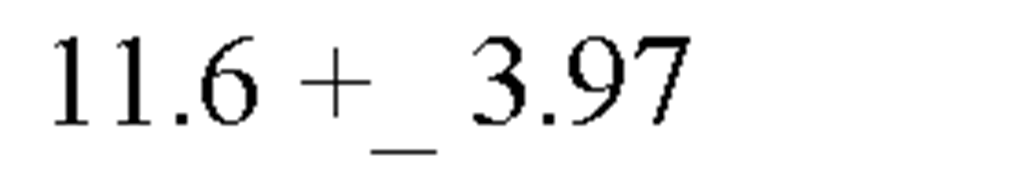

0.98 +_ |

1.40 |

50.8+_ |

31.47 |

0.000 |

2.04+-1.42 |

30.38+-22.16 |

<0.001* |

|

It is noted that all AHI values have been dichotomized at its level of 5. Such a situation, in which BMI as a result has become marginally not significant upon independent sample t test (p= 0.069) in the Taiwanese (Tang, 2007) study, whereas that of the Filipino Conde-Corpuz’s study has been significant (p=0.001) as tabulated as above. (The rest of discussion as per vide supra: the full text). In this Table, following the pattern the data were recorded in the Philippine Conde-Corpuz’s study, it is noted that the t test instead of Mann Whitney test was used. (The rest of discussion as per vide supra: the full text, and vide infra: the Table 6) In this Table, it is as well noted that in that Taiwanese study, the difference of the BMI, is merely 2.02, whereas that in the Filipino study is 4.3, two folds of that of Taiwanese study. (The rest of discussion as per vide supra: the full text)

For another example, in one of the U S studies reveals that Tractrenberg et al’s finding is as follows. Their 2006 and 2005 articles are based on a large sample recruited from the community, and not from a sample with sleep disturbances. Their data may be useful as an external (independent) reference for the samples cited in this study. Hence, comparing studies referred in this article, Tractenberg et al had the analysis based on the intake interviews of 399 healthy non-demented elderly whose data were achieved as of September 2002. (Tractenberg, 2003 and 2006) (Table 5) In their studies, those participants who were non-demented elderly people had the frequency rating of heavily snoring from 0.7 +_ 1.1 to 0.9 +_ 1.2. Noticeably, on the frequency measure of heavy snoring, its rating was defined as following: 0, for rating for no snoring in previous month, that is, never; 1, less than once per month; 2, at least once per month, 3, at least once per week; and 4 nearly everyday per day/night.

Table 4. Comparison of Summary of Characteristics in Those with OSA in studies between Two Societies

Table 5. Table of Comparison for Prevalence of Snoring and Insomnia

Snoring

As a comparison, it is interesting to notice that in the U S, a) on Tractenberg et al’s reports (2003, 2006), the criteria of the frequency of snoring is defined as: 0 for never; 1 for less than once per month; 2 for at least once per month; 3 at least once per week; and 4 nearly everyday per day/night.

Conversely, the literature estimates the prevalence of habitual snoring in general population ranges from 3.6% to 35.7%. (Rice et al, 1986; Koskenvuo et al; Young et al, 1993) In one of the studies in Taiwan (Tang, 2007), it investigated the subjects of a sleep-medicine-laboratory based cohorts, who lived in the dwelling communities of Changhua area, Mid-Taiwan, which is adjacent to Taichung area. The snoring prevalence in Taichung area, Taiwan is 47.8 % for males, whereas 37.2 % for females with age ranging from 10 to older than 60 years, all together 1,252 people who were successfully interviewed, whereas 606 were males and 646 were females, according to a report by Liu and Liu (2004) on the prevalence of snoring in a regional area of Mid-Taiwan.

Snoring as a risk factor for stroke has been reported in the Philippines as well. Sawit (2006) has extensively reported with its relevance to sleep apnea. Snoring is a not only an independent risk factor for acute vascular disease, but also a factor for stroke and myocardial infarction. In addition, habitual snorers are more at risk for acute vascular disease compared to occasional snorers. Taiwan is short of such studies except one by Liu & Liu (2004). They merely reported the prevalence of snoring in a regional area of Mid-Taiwan. Further studies to inquire on the relationship of sleep apnea with snoring in Taiwan should be done.

BMI and Environment

BMI has been affected by urbanicity and obesigenic nature of environment. For example, I-lan County, located at the northwestern region of Taiwan, is a rural area with high labor work (e. g. farming). There, body weight tends to be lower. Urbanites tend to have higher BMIs than their rural counterparts. As rural area became more urbanized in I-lan County, the relationship between urbanicity and obesigenic nature of environment merits further consideration. In Taiwan and the Philippine societies, modernization of certain rural areas leads to an increase in their body weight. This aspect of modernization has exerted a strong influence on the debates on the role of agriculture as a prerequisite for developing countries. Ishikawa (1967), Johnston ( 1969), Kelley and Williamson ( 1971), and Hayami (1974) to contribute to this debate.

The Comparison of BMI among Three Sleep Studies between Two Societies

Three studies between two societies are contrasted. BMI was marginally not significant upon independent sample t test (p= 0.069) in the Taiwanese (Tang, 2007) study, whereas that of the Filipinos Conde-Corpuz’s study was significant (p=0.001) as tabulated in Table 2. In Table 2, the t test instead of the Mann Whitney test was used in the Filipino Conde-Corpuz’s study.

The updated census data for Taiwanese BMI (2000) was 18.5-24 (applied to all ages), issued by the Health Department of Taiwan ( http://www.doh.gov.tw/ ). An earlier (19931996) survey conducted by the same department concluded that BMI for subjects with 19-44 years old > 26.4 would be classified as obese. The census data of BMI in the period from 2001 to 2003 was 20-24.9 ( http://www.doh.gov.tw/ ). With respect to the comparison of BMI (and other basic parameters) between non-snores and snorers in two different societies, by examining Table 1 of this article, it is, as well, noted that in the Taiwanese study (Tang, 2007), the difference of BMI between non-snores and snorers is 2.02; that in the Filipino study in Table 1 is 4.3, twice that of Taiwanese study (Table 2). All AHI values in Table 3 have been dichotomized at a level of 5. BMI was a result has become marginally not significant upon independent sample t test (p= 0.069) in the Taiwanese study, whereas that of the Filipino Conde-Corpuz’s study (Conde-Corpuz) was significant (p=0.001) (Table 3).

The Significance of Marginally Not Significant (P Value = 0.069, Instead Of 0.05) in Measurement (Table 3)

With regard to the fact that AHI values in Table 3 have been dichotomized at a level of 5 and BMI was a result has become marginally not significant upon independent sample t test (p= 0.069) in the Taiwanese study, it merits evaluation as follows.

The p value suggests a "very small amount of evidence in support of the null hypothesis". It does not suggest that the difference (the alternative hypothesis) is true, because p-values are strictly related to the null, and not the alternative, hypotheses. Thus, a p value = 0.069 is "marginally not significant" is the most appropriate; one should not attribute any characteristic apart from marginality to the p-value.

The Importance of Gender Factor

The prevalence of OSA in patients up to the age of 60 is two times higher in men than in women (Franco, 2004). The gender data on BMI in one of the Taiwanese study (Tang, 2007) is consistent with the literature.

The Importance of Who was Doing Measurement of Height and Weight

In Denmark and the U S, a self-reported measurement of height and weight is strongly i practiced. The height and weight data are predictors of health outcomes (Stunkard & Albaum, 1981; Troy et al., 1995). Most studies involving BMI are in conjunction with data of height and weight. The key issue is whether they are self-reported or not. In a Taiwanese studies (Tang, 2007), a clinical research was carried out on individuals aged from 65 to 88.5 years; PSG technologists measured 117 individuals’ height and weight before PSG testing. BMI was then calculated. There was no chance for self-reported bias. Anthropometric indicators of height measures may underestimate BMI because people of short people may over report their height, and heavy individuals may under report their weight (Black, Taylor, & Coster); this aforementioned can happen in any society regardless of cultures.

The Significance of Asian BMI

Researchers modified WHO expert committee’s suggestion and used the criterion of > = 27 instead of >= 30 for Asian BMI. The upper limit of normal BMI in Far-East Asian is 23.5 kg/m2 from new WHO data. Obesity in Asia, as in Singapore nationwide, is defined as BMI >23. Asian nutritionists are inclined to apply a limit of BMI > 23kg/m2 for obesity due to lower stature and body weight in Asians. Asian BMI allows for a smaller skeleton (physical) frame, of most Asians. For every height, weight is set lower to compensate for the smaller frame.

The current WHO data the upper limit of the normal Asian BMI is 23.5 kg/m2; this been as well applied in Singapore nationwide. Singapore nationwide protocol reveals that the scales that have been compiled using a nationwide survey data in Singapore. If one is not an Asian or an Asian descendent, Asian BMI will not be applicable. For example, census data of BMI from 2001 to 2003 in one of Taiwanese studies (Tang & Chen, 2003) is 20-24.9 kg/m2 .

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may not be uncommon in Asian and Southern Pacific patients (Tan W. C., 2004) compared to what has been reported for Western patients (Duran J et al, 2001; Redline, S. et al, 2004). Several studies comparing OSA between Caucasians and Asians have shown that Asian subjects have a greater severity of illness, as indicated by high AHI, when contrasted with Caucasian patients matched with age, gender, and BMI (Fletcher, 1995; Pawer et al, 1996). Asians generally have a higher percentage of body fat than Caucasians. Hence, making cross-ethnic comparison of body structures by using absolute BMI values may be misleading. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of OSA. (Young, Peppard, Gottlieb, 2002; Fletcher, 1995; Pawer et al, 1996; Hoffstein et al, 1991). Therefore, OSA’s association with BMI in Asia should be evaluated with Asian BMI criteria.