Richard II was born on January 6, 1367, at Bordeaux in the duchy of Aquitaine. With the death in 1376 of his father, Edward of Woodstock, the Black Prince, Richard became heir to his grandfather, Edward III of England, whom he succeeded in 1377 at the age of ten. His reign of twenty-two years saw a number of domestic crises, from the Peasants’ Revolt (1381) to later conflicts with a disaffected nobility, culminating in his usurpation by his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke (crowned Henry IV). Richard was deposed in September 1399 and died in captivity at Pontefract Castle in February 1400, events made familiar through their dramatization in Shakespeare’s Richard II.

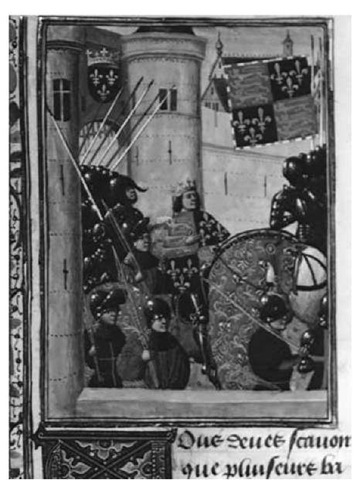

Richard II goes to Ireland from Froissart’s Chronicles (Volume IV, part 2).

Richard was the first English king to visit the lordship of Ireland since John in 1210 and the only reigning monarch to make two such expeditions. This unusual degree of involvement has prompted historical speculation about his motives and degree of success, for although recurring crises may have justified royal intervention no other monarch responded to the lordship’s needs with such a commitment. In recent biographies drawing on modern studies of Richard’s reign, English historians have set his aspirations in a wider British context, linking his policies in Ireland with those in other peripheral regions and with his views on royal authority and the obedience of subjects.

By the time Richard became king, the Irish lordship was regularly requiring support from England to meet its critical military and financial needs. In 1385, a council in Dublin asked for personal royal intervention. Sustainable recovery could not be effected by passing the burden to chief governors, whether the king conferred authority on them by military indenture or, as in 1385 with Robert de Vere, Marquess of Dublin, by the grant of extensive powers commonly reserved to the crown. In these circumstances, amid fears of the lordship’s complete collapse, Richard’s first Irish expedition (1394-1395) was an extraordinary success.

Richard arrived in Ireland in October 1394 with a substantial force. His primary objectives were military and political, but he also intended administrative and financial reforms. The presence of the king in Ireland provided an unprecedented opportunity to establish peace between the different interests in the country. A combination of diplomacy and of overwhelming force, demonstrated in the defeat of Art Caeanach Mac Murchada in Leinster, won the submission of Gaelic Ireland. Correspondence from the rebel Irish lords records their willingness to accept the English crown and their desire that Richard arbitrate in their disputes with the English of Ireland. Richard accepted this position as the basis for a common approach to all the submitting Irish. Rather than focus on their punishment for past rebellion, he welcomed the Irish lords as his lieges, requiring them to make oaths of allegiance that effectively recognized their status as his subjects. Special sensitivities within some areas called for additional arrangements. In Leinster, an area of particular difficulty because of Mac Murchada’s authority and the lordship’s vulnerability, he attempted to revitalize the English interest, requiring the Irish to yield lands they had seized and making grants to English knights. In Ulster, however, there had been no resolution of the differences between Ua Neill and Roger Mortimer, earl of Ulster, when Richard left Ireland in April 1395.

Although little evidence survives about the lordship’s government and administration in the 1390s, occasional references show that in the following years Richard attempted, for a time, to maintain his expeditionary settlement. It was from the start under great pressure, protected by a greatly reduced military capacity. The collapse of the fragile peace was hastened by many factors. These included the unresolved difficulties between Gaelic Ireland and the lordship, the ambitions of local lords, the crown’s dependence on Mortimer as lieutenant, the conflict within the Irish administration, and the financial and political problems in England that demanded Richard’s attention.

In late 1397, with the Irish lords of both Ulster and Leinster once more at war, Richard was already planning to return. His second expedition, in June and July 1399, again brought a significant army to Ireland, but in less favorable circumstances. The campaign in Leinster was already in difficulty when the venture was cut short by news of Bolingbroke’s return to England in arms against Richard. The bulk of the expeditionary forces withdrew in haste and disorder from Ireland, leaving behind a vulnerable lordship and, for both Gaelic Ireland and the Anglo-Irish community, a message of royal impotence. Richard’s Irish aspirations ended in failure, both for himself and for the English interest in Ireland.