Two of Patrick’s Letters, the Epistola ad Milites Corotici, written to soldiers of a petty king who had killed some of his catechumens and enslaved others, and the Confessio, written to explain and justify his mission to converts and critics alike, tell what he wanted us to know of his life as Apostle of the Irish.

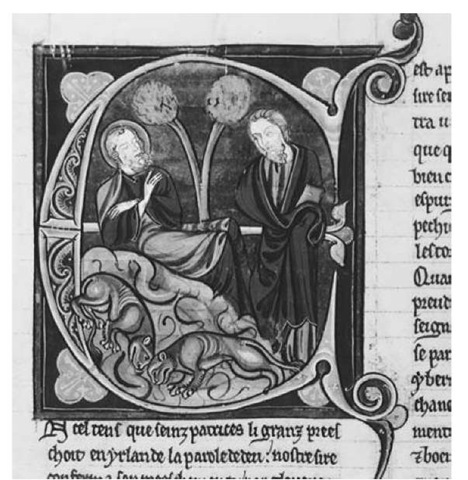

St Patrick asleep on a knoll.

The Letters survive in eight manuscripts: the earliest giving an abridged text copied at the beginning of the ninth century in Armagh; a second during the tenth century, perhaps in the diocese of Soissons; a third about the year 1000 at Worcester; a fourth during the eleventh century, owned if not written at Jumieges; three during the twelfth century in northern France and in England; and one during the seventeenth century. As among these eight manuscripts seven are independent of each other, the text of the Letters is fairly secure.

Patrick wrote the name of his grandfather as Potitus, which means "empowered man," and the name of his father as Calpornius, associated with the name of the Roman plebeian gens Calpurnius and the name of Julius Caesar’s wife Calpurnia, derived from Ka^rcn + urna + -ius, designating one who bears a "pitcher" or "urn" in religious ceremonies. Patrick’s own name, derived from pater + -icius, meaning "like a father," designates "a man noble in rank." Because of the meaning of his name and because of the status of his family Patrick explicitly claimed nobilitatem "nobility" for himself. He described his grandfather as a presbyter "priest" and his father as both a diaconus "deacon" and a decurio "decurion," a member of a municipal senate, an official responsible for the rendering of taxes. His father owned slaves of both sexes and land, a villula "little villa" near Bannavem Taburniae, perhaps Bannaventa Berniae "market town at the rock promontory of Bernia." Although some would identify Bernia with the territory of people described in Old Welsh as Berneich and in Anglo-Latin as Bernicii, inhabitants of the northern province of the kingdom of Northumbria, and one later Life states that Patrick was born in Strathclyde, the northern part of Britain was a military zone. Patrick’s Roman Christian family of landowning and slave-holding clerics and imperial civil servants are likelier to have lived somewhere in the civilian zone of southwestern Britain, along the Severn estuary, where Ordnance Survey maps show many villas. As Patrick describes his fatherland in the plural as Brittanniae "the Britains" and neighboring regions as Galliae "the Gauls," he must have been born while these regions were still divided into multiple provinces in which Roman ecclesiastical and civil administration still functioned, perhaps about a.d. 390, certainly before 410. As he refers incidentally to coinage, solidi and scriptulae, and contrasts the behavior of the presumably post-Roman tyrannu Coroticus (a name related to Old Welsh Ceredigion, modern Cardigan) with that of Romano-Gaulish Christians dealing with pagan Franks, his mission probably preceded the conversion of the Franks, perhaps in 496, certainly before 511. This is consistent with dates of The Annals of Ulster, which record Patrick’s arrival as a missionary in Ireland in 432, his foundation of Armagh in 444, and his death in 461, when he would have fulfilled the Biblical span of 70 years, alternately 491, when he would have been about 100.

Captured as a 15-year-old adolescens "adolescent" (15-21) on his father’s villula, Patrick worked as a slave for six years near the Forest of Foclut in Ireland, where began a series of seven dreams that informed his career. After learning in the first that he would escape to his fatherland he journeyed 200 Roman miles (188 of ours), presumably from northwest to southeast across Ireland, whence he sailed for three days. On landing, his company wandered for 28 days through wilderness, nearly starving until discovery of food after Patrick’s prayer for help. There followed a great temptation by Satan in a second dream, escape from perils which lasted one month, an account of a later dream which foretold accurately a captivity of two months, then return to his family in Britain, and a fourth dream in iuuentute "in youth" (22-42), in which a man named Victoricius, sometimes identified with Victricius bishop of Rouen (c. 330-c. 407), bore a letter with the Vox Hiberionacum "the voice of the Irish" summoning him to evangelize them. In the fifth dream Christ spoke within him. In the sixth he saw and heard the Holy Spirit praying inside his body, super me, hoc est super interiorem hominem "above me, that is above my inner man." In the triumphant seventh vision, following his degradation, he was joined to the Trinity as closely as to the pupil of an eye.

After the raid by Coroticus Patrick sent a letter seeking redress with a priest quem ego ex infantia docui "whom I have taught from infancy" (implying, since infancy ended at 7 and ordination to the priesthood occurred at 30, that he had been in Ireland more than 23 years). Rejection of that letter elicited the letter of excommunication we know as the Epistola. As Patrick states in it Non usurpo "I am not claiming too much," one infers that his critics believed he was exceeding the limits of his authority. His attempt to excommunicate from Ireland a tyrant in Britain may have provoked the attack that he relates at the thematic crux of the Confessio, an attack on his status as bishop when he was at least 51, in his senectus "old age" (which began after 42) by ecclesiastical seniores "elders" in Britain who tried him during his absence. They charged him with a sin, committed when he was 14, confessed at least 7 years later, after escaping from Ireland, before becoming a deacon. The sin was revealed by the amicissimus "dearest friend" to whom he had confessed it, the man whose statement Ecce dandus es tu ad gradum episcopatus "Behold, you are bound to be appointed to the grade of bishop" stands at the symmetrical center of the Confessio.

Although modern scholars have supposed that Patrick was poorly educated, a barely literate rustic who struggled to express himself in a language he could not master, his two extant Letters are, not by Ciceronian standards, but certainly by Biblical standards, masterpieces. If Patrick was a homo unius libri "a man of one book," that book was the Latin Bible, which he quoted both economically and brilliantly, using its phrases to claim identity of his vocation and mission with those of the Lawgiver Moses and the Apostle Paul, relying upon readers’ knowledge of the unquoted contexts of his quotations and allusions to clarify his explicit meanings, to suggest implicit overtones and undertones, and to attack his critics. To establish his literary credentials he composed in Ciceronian clausular rhythms, which he arranged by type, only in the paragraph of the Confessio in which, addressing domini cati rethorici "lords, skilled rhetoricians," he appears to proclaim his ignorance. Elsewhere his cursus rhythms, like his Biblical orthography, diction, and syntax, are faultless. His prose, arranged per cola et commata "by clauses and phrases," exhibits varied forms of complex word play. Every paragraph is both internally coherent and bound in larger patterns within comprehensively architectonic compositions, in which every line, every word, every letter has been arithmetically fixed. His prose consistently evokes Biblical typology, an effective means of linking the events of his personal life with sacred and universal history.

Patrick nowhere states that he brought any ecclesiastical assistants with him from Britain, but he affirms repeatedly that he is a bishop in Ireland, referring often to those converted, baptized, confirmed, ordained as clerics, and admitted to the religious life as both monks and nuns in Ireland. He never describes his education, nor does he name any authoritative teacher or ecclesiastical patron. In stating at the beginning of the Epis-tola that he is indoctus he does not lament that he is "unlearned;" rather he proclaims that he is "untaught" by men, and he continues directly Hiberione constitu-tus episcopum me esse fateor. Certissime reor a Deo accepi id quod sum "established in Ireland I confess myself to be a bishop. Most certainly I think I have received from God what I am." He mentions his dealings with Irish kings, praemia dabam regibus "I habitually gave rewards to kings," with the sons of kings in his retinue, dabam mercedem filiis ipsorum qui mecum ambulant "I habitually gave a fee to the sons of the same [kings] who walk with me," with the lawyers or brehons qui iudicabant "who customarily judged," to whom he distributed non minimum quam pretium quin-decim hominum "not less than the price of fifteen men," with noble women, una benedicta Scotta genetiua nobilis pulcherrima adulta erat quam ego baptizaui "there was one blessed Irish woman, born noble, very beautiful, an adult whom I baptized," and with others quae mihi ultronea munuscula donabant et super altare iactabant ex ornamentis suis, et iterum reddebam illis "who habitually gave to me voluntary little gifts and hurled them upon the altar from among their own ornaments, and I habitually gave them back again to them."

Though Patrick mentions no absolute date, he makes it abundantly clear that the milieu in which he lived and worked was late-Roman and post-Roman Britain and Ireland of the fifth century. From at least the sixth century onward Patrick has been revered as the effective founder of the Church in Ireland, celebrated in the panegyric "Saint Sechnall’s Hymn" Audite Omnes Amantes Deum composed probably during the fourth quarter of the sixth century and quoted during the seventh. Patrick is cited as papa noster "our father" in Cummian’s Letter about the Paschal controversy written in the year 633 to Segene, Abbot of Iona, and the Beccan the Hermit. There are references to three lost Lives of Patrick written by Bishop Columba of Iona, Bishop Ultan moccu Conchobuir of Ardbraccan, and Aileran the Wise, Lector of Clonard by the middle of the seventh century. From the end of the seventh century a hagiographic dossier in support of the metropolitan claims of the church at Armagh includes memoranda, Collectanea, by Tirechan, a pupil of Bishop Ultan, and a Vita by Muirchu moccu Mactheni, a pupil of Cogitosus of Kildare. By the end of the eleventh century or the beginning of the twelfth there were four additional Vitae.

The Synodus Episcoporum or "First Synod of Saint Patrick," extant in a single manuscript copied from an Insular exemplar and written at the end of the ninth century or the beginning of the tenth in a scriptorium under the influence of Tours, may have issued from a synod between 447 and 459 by the missionaries Palladius, Auxilius, and Isserninus, the former sent in 431 by Pope Celestine ad Scotos in Xpistum credentes "to the Scots [i.e., Irish] believing in Christ," the text attracted to the Patrician dossier by propagandists at Armagh in the seventh century.

Patrick is commemorated on March 17.