Edward Bruce, lord of Galloway (from 1308), earl of Carrick (from 1313), and king of Ireland (1315-1318), was a younger brother of Robert I of Scotland (1306-1329). He was heir-presumptive to the Scottish throne when he invaded Ireland in May 1315, and did so with King Robert’s full support. It was alleged against members of the Anglo-Irish de Lacy family that they invited Edward (presumably to help recover the lordship of Mide [Meath] lost to the family through the female line), but one contemporary claimed that Edward was invited by a nobleman with whom he had been "educated," possibly a reference to fosterage as practiced in the Gaelic world and by the Bruces. The obvious candidate is Domnall Ua Neill of the Northern Uf Neill, who acknowledged his role in a letter to the pope in 1317, adding that he voluntarily ceded to Edward his own hereditary royal claim.

The assembly that met on April 26, 1315, at Ayr, facing the Antrim coast, was perhaps a muster for the fleet that sailed from there, landing on May 26, possibly at Larne, or Glendun farther north (Robert Bruce was there in July 1327), where Edward had a land-claim inherited from his great-grandfather Duncan of Carrick (in Galloway). The 6,000 troops landed without opposition, the Anglo-Irish government being taken unawares, with the chief governor in Munster and the earl of Ulster, Richard de Burgh, in Connacht. The earl’s tenants—Sir Thomas de Mandeville, the Bissets, Logans, and the Savages—took to the field unsuccessfully against the Scots under Thomas Randolph, earl of Moray, and when the invaders marched on Carrickfergus, the town fell easily, although its heavily fortified castle required a prolonged siege. Probably while at Carrickfergus, up to twelve Irish kings came to Edward and, the annals record, he "took the hostages and lordship of the whole province of Ulster without opposition and they consented to his being proclaimed King of Ireland, and all the Gaels of Ireland agreed to grant him lordship and they called him King of Ireland."

King Edward Bruce now campaigned along the Six Mile Water, burning Rathmore near Antrim, before heading south through the Moiry Pass, where Mac Duilechain of Clanbrassil and Mac Artain of Iveagh apparently ambushed him. But on June 29, 1315, Bruce stormed the de Verdon stronghold of Dundalk, which he ransacked, including its Franciscan friary. The chief governor, Edmund Butler, assembled the feudal host, and de Burgh gathered his Connacht tenants (and Irish levies under Feidlim Ua Conchobair) and both converged south of Ardee around July 22. The Scots and Irish were ten miles away at Inniskeen, and after a skirmish near Louth Edward cautiously adopted Ua Neill’s advice and retreated via Armagh to Coleraine, which they burned, sparing the Dominican friary but demolishing the bridge over the Bann. De Burgh alone pursued Bruce to Coleraine but was forced to withdraw to Antrim for lack of provisions (being also weakened by Ua Conchobair’s return to Connacht). When the Scots crossed the Bann in pursuit, aided by the sea captain Thomas Dun, they defeated de Burgh in battle at Connor on September 1, and he withdrew humiliated to Connacht, the annals calling him "a wanderer up and down Ireland, with no power or lordship."

In mid-November Edward again marched south, and by November 30 was at Nobber, County Meath, where he left a garrison and advanced on Kells to challenge Roger Mortimer, lord of Trim, whose large but disloyal army fled the battlefield around December 6, Mortimer himself returning to England. Bruce burned Kells and turned west to Granard, County Longford, attacking the Tuit family manor and the Cistercians at Abbeylara (accused in Ua Neill’s "Remonstrance" to the pope of spear-hunting the Irish by day and saying Vespers by evening). Edward raided the English settlements in Annaly, County Longford, and spent Christmas at Loughsewdy, caput of the de Verdons’ half of Meath, before razing it to the ground. Meath manors (like Rathwire) still in de Lacy hands were untouched by Bruce, suggesting they had joined him, for which they were later convicted and dispossessed.

Edward next appeared in Tethmoy, County Offaly, home of the de Berminghams, adversaries of the de Lacys, apparently being waylaid in Clanmaliere by O’Dempsey, who remained loyal to the Dublin government. Having reached the lands of John FitzThomas (soon to be earl of Kildare, and second only to de Burgh among the resident Anglo-Irish baronage), Bruce attacked Rathangan castle and progressed to Kildare itself, but the garrison refused to surrender. Travelling to Castledermot, then north again via Athy and Reban, Edward was near the mound of Ardscull when the colonists assembled to deal with the threat. Led by Butler, John FitzThomas and his son, their cousin Maurice FitzThomas of the Munster Geraldines (later first earl of Desmond), and members of the Power and Roche families, the colonists faced the Scots in battle at Skerries near Ardscull on January 26. Although the government army exceeded Edward’s, quarrels among its leaders handed victory to the Scots, despite heavier losses.

Bruce then retired into Laois, safe among Irish supporters and boggy terrain unsuitable for cavalry. The routed Anglo-Irish retired to Dublin and swore on February 4, 1316, to destroy the Scots on pain of death. Edward II’s envoy, John de Hothum, wrote from Dublin urgently requesting £500 to replenish a treasury empty because of the war and the famine (felt throughout Europe) that had followed unusually bad weather and a disastrous harvest. Bruce too found Irish enthusiasm waning, as they blamed him for the desperate conditions that coincided with his occupation, and was unable to push home the advantage after Skerries. He burned FitzThomas’s fortress at Lea, County Laois, and by February 14 was near another Geraldine castle at Geashill. But the government army was now assembling near Kildare. Bruce retreated, his army being reported at Fore, County Westmeath soon after, dying of hunger and exhaustion, arriving back in Ulster base by late February.

After reputedly holding a parliament in Ulster, Edward visited Scotland briefly in late March. Car-rickfergus Castle still held out, despite Thomas Dun’s sea blockade, although the garrison was reportedly reduced to cannibalism and, by September 1316, had surrendered (under terms that Edward, characteristically, honored). He also captured but re-lost Greencastle, County Down, and secured Northburgh Castle in Inishowen. Robert Bruce himself was rumoured to be in Ulster late that summer but cannot have been there long (if at all), since on September 30, Edward was at Cupar in Fife with Robert and the earl of Moray, where, styling himself "Edward, by the grace of God, king of Ireland," he approved his brother’s grant to Moray of the Isle of Man. Edward perhaps had designs on Man himself and agreed to this in return for reinforcements in Ireland. Help was certainly needed, as the tide was turning against him. In October 1316, Edward II put a bounty of £100 on his head, and soon afterwards 300 Scots men-at-arms were killed in Ulster.

King Robert therefore set sail for Carrickfergus from Loch Ryan in Galloway, arriving about Christmas, the annals noting that he brought a great army of galloglass ( Hebridean warriors) "to help his brother Edward and to expel the foreigners from Ireland." By late January 1317, they were on the move, allegedly numbering 20,000 by the time they reached Slane, County Meath in mid-February, ravaging the countryside as they went. The earl of Ulster was at Ratoath manor and possibly attempted to ambush the Scots, but he failed and fled to Dublin, taking refuge in St. Mary’s Abbey. The citizens panicked and the mayor seized the de Burgh family and imprisoned them in Dublin Castle, suspecting collusion with the Scots: Earl Richard had a thirty-year association with the Bruces, and in 1302, Robert Bruce married Richard’s daughter (now queen of Scotland), but they were no longer allies and the suspicions seem unfounded.

By February 23, King Robert was at Castleknock, and the Dubliners strengthened their defenses by dismantling the Dominican priory to fortify vulnerable stretches of the city walls near the bridge across the Liffey. They also fired the western suburbs to deny the Scots cover, and, although the conflagration raged beyond control and did enormous damage, the tactic worked. The Bruces did not risk a siege and, joined by the de Lacys, headed via Naas to Castledermot, where they burned the Franciscan friary. They proceeded through Gowran, County Kilkenny, reaching Callan by March 12. The Anglo-Irish were assembled in Kilkenny (led by the justiciar Edmund Butler, the second earl of Kildare, Maurice FitzThomas of Desmond, and Richard de Clare of Thomond), but dared not oppose the Scots in battle, who continued into Munster where they plundered Butler’s town of Nenagh. The O’Briens had led Bruce to expect widespread support but, as with the O’Conors in Connacht, local rivalries intervened. So, having seized de Burgh’s fortress at Castle-connell on the Shannon, putting Limerick within sight, the Scots proceeded no further. Butler led 1,000 men toward them in early April and, as hunger took its toll (the famine being even more severe than in 1316), Roger Mortimer, now king’s lieutenant, landed at You-ghal with fresh troops and began marching north. King Robert sensed the danger and began a retreat. His hungry and exhausted troops, having sheltered for a week in woods near Trim, struggled back to Ulster about May 1, whereupon Robert returned to Scotland, apparently not reappearing in Ireland for nearly a decade.

The fourteenth-century verse biography known as The Bruce records another gathering of the Irish at Carrickfergus, after which "every one of the Irish kings went home to their own parts, undertaking to be obedient in all things to Sir Edward, whom they called their king." Ua Neill then wrote to the pope on behalf of "the under kings and magnates of the same land and the Irish people" seeking papal support for the invasion. Nothing further is known of events for the next eighteen months until, after a bumper crop in that year’s harvest, Bruce marched south again in October 1318. With the de Lacys in tow, anxious to recover their Meath lands and do down their occupiers, they headed for Dundalk, property of the de Verdons (who held half of Meath), when they were met by an opposing force on a hillside near Faughart on October 14. Their opponents were the de Verdons and their tenants, commanded by John de Bermingham of Tethmoy, an old antagonist and keeper of the half of Meath acquired by Roger Mortimer.

Although reinforcements were purportedly on their way from Scotland, Edward did not wait, and rushed to battle accompanied by Hebridean galloglass under Mac Domnaill and Mac Ruaidri (both of whom were killed). Amid intense fighting, he himself was slain by a townsman of Drogheda, whose body was later found resting on that of the vanquished "king of Ireland." Contrary to local tradition, Bruce was not buried at Faughart, but was decapitated and his body quartered, one quarter, with his heart and hand, being sent to Dublin, the others to "other places." The victor, de Bermingham, brought Bruce’s head to Edward II, who rewarded him with the new earldom of Louth. The collapse of Bruce’s regime was joyously greeted by the Anglo-Irish, and probably went unlamented by the Irish too (one native obituarist certainly condemns him) because, after three years of war and famine, Edward inevitably found himself being blamed for events beyond his control. His claim to Ireland died with him, and was not resurrected by his heirs.

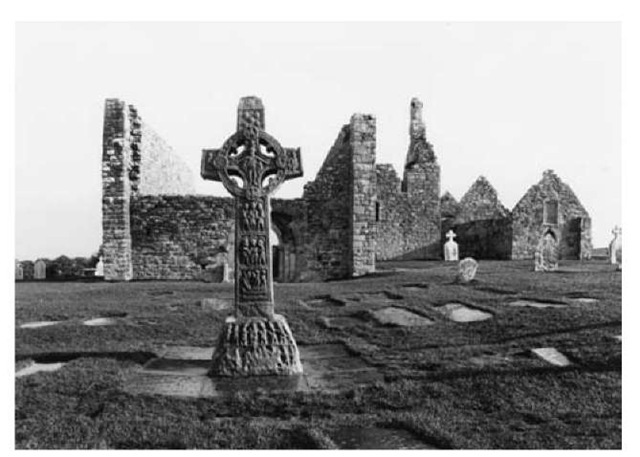

Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly.