Terminology is sometimes problematic in the study of medieval religious communal life and its material remains in Ireland, especially in the period before 1100. The erstwhile assumption of scholars that all ecclesiastical sites of the early Christian period, up to and including the age of Viking incursions, were monastic has given way in recent years to greater caution, driven by an increasing awareness of the complexity of the early Church’s institutional and territorial structures, and of its provision of pastoral care to contemporary society. Strictly speaking, the designation "monastery" indicates the one-time presence of monks living in community according to a Rule, a code of behavior prescribed by one of the early church’s intellectual heavyweights, and while many of the sites were certainly monastic by this measure, the organization and practice of religious life at many other sites— especially those small, archaeologically attested but barely documented, sites—simply remain unknown.

Claustral Planning

Religious foundations of the twelfth century and later generally have better documentary records, as well as higher levels of fabric-survival, so problems of interpretation and terminology are considerably less acute. Churches and associated building complexes designed for worship and habitation by religious communities are easily identified, and hence the adjective "monastic" can be used more confidently. Unlike pre-1100 foundations, most of these monasteries were claustrally planned. This claustral plan, which originated in continental Europe before a.d. 800 and first appeared in Ireland around 1140 (at Mellifont), comprised of a central square or rectangular cloister (clustrum, courtyard) with the key buildings arranged around it and fully enclosing it. The church was usually on the north side, the refectory (dining hall) was always on the side directly opposite, and the chapter house (a ground-floor room wherein the community assembled daily to discuss its business) and dormitory (a long first-floor room) were on the east side. The west side of the cloister comprised cellarage and additional habitation space; in Cistercian abbeys the con-versi, lay brethren who undertook much of the manual work, were accommodated here. What made the claustral plan so attractive across the entire monastic landscape of high medieval Europe was its practical efficiency: Distances between parts of the monastery were maximized or minimized according to the relationships between the activities carried out in them. Moreover, its tightly regulated plan was a fitting metaphor for a monastic world that was itself highly regulated.

Abbeys, Priories, Friaries

Popular local tradition in Ireland, commonly abetted by ordinance survey maps, usually identifies twelfth-century and later monasteries as "abbeys," but is often incorrect in doing so. Less than a quarter of the 500-plus establishments of religious orders founded in post-1100 Ireland were genuinely abbeys, communities of male or female religious under the authority of abbots or abbesses. Of slightly lower grade were priories, communities of male or female religious presided over by priors or prioresses, officers of lower rank than abbots and abbesses; these were more numerous than abbeys, and constituted about one-third of that total. Friaries, communities of friars (literally, brothers) whose main work was preaching, make up most of the very significant remainder.

The abbeys and priories of twelfth- and early-thirteenth-century Ireland are mainly associated with the Augustinian canons regular, priests living according to the Rule of St. Augustine, and, in the case of abbeys only, the Cistercian monks, followers of the Rule of St. Benedict. Monasteries of both groups survive in significant numbers in areas formerly under Gaelic-Irish and Anglo-Norman control. Priories of Augustinian canons regular occur more frequently in urban settings than the monastic houses of other orders, in part because of their willingness to engage in pastoral work, their modest space requirements, and their presence in Ireland at the time of colonization.

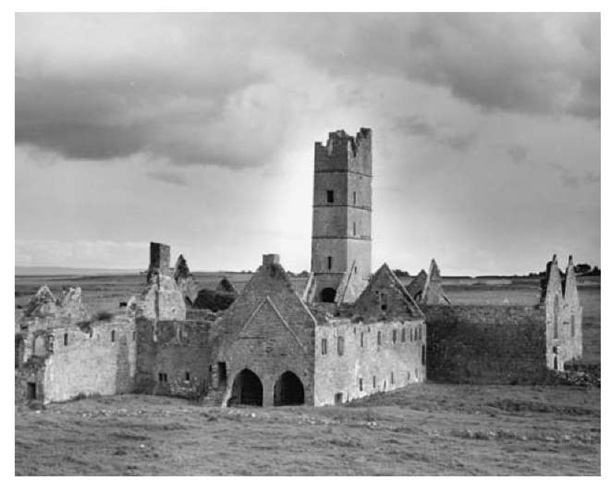

Moyne Abbey, Co. Mayo.

There were also other orders present in Ireland at this time, but they have left behind little above-ground archaeology. Premonstratensian canons, for example, had about a dozen houses in Ireland, but little remains of any of them. The sole house of Cluniac monks, founded by Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair at Athlone circa 1150, is lost. Carthusian monks from England had one house, Kinalehin, founded circa 1252; dissolved ninety years later and then re-colonized shortly afterwards by Franciscan friars, the archaeological remains are mainly Franciscan, though elements of the Carthusian priory and fabric are still evident. There were also about seventy convents of nuns, mainly Augustinian canonesses. Of the few that survive, the nunnery of St. Catherine near Shanagolden stands out: Its church projects from the middle of the east side of the cloister, a very idiosyncratic arrangement.

Benedictine Houses

Benedictine monks were also present in Ireland, including some at Christ Church cathedral in the late 1000s, but they had surprisingly few houses there compared with contemporary England, where they enjoyed the patronage of the Normans. Malachy’s energetic promotion of the Cistercians and Augustinians as the landscape of reformed monasticism in Ireland was taking shape was evidently to their cost. A couple of Benedictine houses, Cashel and Rosscarbery, were subject to Schottenkloster (Irish Benedictine monasteries in central Europe) but we know virtually nothing about their archaeology or architecture. Ireland’s most substantial medieval Benedictine survival is at Fore, a late-twelfth-century foundation of the Anglo-Norman de Lacy family; the fabric of this claustrally planned monastery was altered considerably during the Middle Ages, but parts of the original church of circa 1200 remain.

Cistercian Houses

The Cistercian order, founded in 1098 in Burgundy, was a pan-European institution in the twelfth century, and its arrival in Ireland in 1142 is one of the key moments in the country’s history. Fifteen Cistercian abbeys were founded in the thirty years before the Anglo-Norman invasion, and twice as many again were founded (by both Anglo-Norman and native Irish patrons) in the subsequent century. The last medieval foundation was at Hore, near Cashel, in 1272.

Cistercian architecture in Europe has a distinctively austere personality: The churches are generally simple cruciform buildings with flat-ended, rather than apsidal, presbyteries and transeptal chapels, and their interior and exterior wall surfaces tend to be unadorned. The Irish examples conform to this general pattern even though the two earliest foundations, Mellifont (founded 1142) and Baltinglass (founded 1148) have churches of slightly unusual plans.

Mellifont’s construction was overseen by a monk of Clairvaux, Robert. Little of its original architecture remains. The principal surviving features at Mellifont are the late Romanesque lavabo, an elaborate structure for the collection and provision of water to monks about to enter the refectory, and the slightly later chapter house. Mellifont’s community was originally composed of Irish and French brethren, but racial and cultural conflict between them persuaded the French to leave shortly after the foundation. Similar conflicts emerged and were sometimes resolved after armed conflict when the Anglo-Normans sought control of Ireland’s Cistercian monasteries.

Augustinian Houses

Unlike the Cistercian Order, which entered Ireland in the company of monks from overseas, the Augustinian canons regular of pre-Anglo-Norman Ireland were simply indigenous religious who, in response to the twelfth-century Church reform, adopted the Rule of St. Augustine as a way of life. Of the 120-odd monasteries of Augustinian canons founded in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Ireland, the number established before 1169 is uncertain; that number may be as high as one-third of the total, but the problem is that foundation dates are not as secure as those for Cistercian abbeys. Archaeology is of little help here, as there was no such thing as an "Augustinian style" of monastic architecture at any stage in the Middle Ages.

Anglo-Norman support for Augustinian canons manifested itself in continued patronage of existing houses and in the foundation of new houses. Some of these were very substantial: Athassel priory, for example, had one of the most extensive monastic complexes and one of the finest churches in medieval Ireland, while the now-destroyed St. Thomas’s in Dublin, founded as a priory in 1177 and upgraded to an abbey fifteen years later, was one of Ireland’s small number of mega-rich monastic houses. The claustral plan was widely employed in Augustinian houses founded by Anglo-Normans; there is no evidence of its use in Augustinian contexts prior to 1169 even though the Cistercians were using it from the 1140s.

Friars’ Houses

Friars—Augustinian, Carmelite, Dominican, and Franciscan—first appeared in Ireland in the early thirteenth century, but most of the 200-odd friaries date from the period after 1350, and many of these had Gaelic-Irish patrons. Friary churches tend to be long and aisleless; large transepts were often added to their naves to increase the amount of space available for lay worship. Slender bell towers rising between the naves and choirs are perhaps the most distinctive features of friary churches.

Friaries were also claustrally planned, but their cloisters are generally much smaller than those in Cistercian abbeys or Augustinian priories, and are invariably to the north of the churches rather than to the south, which was the normal arrangement. The cloister ambulatories (or alleyways) themselves were sometimes unusual: Instead of timber lean-to roofs they often had stone-vaulted roofs which also supported the first-floor rooms of the claustral buildings. Consequently, while friary cloister courts often seem rather cramped, the dormitories often seem very spacious.

Beyond the Cloisters

Claustrally planned buildings constituted the functional and geographic inner cores of monastic possessions. Those possessions often included extensive lands with out-farms (called granges). The Cistercians were particularly adept at exploiting such lands.

A well-endowed monastery, whatever its affiliation, would normally have an enclosing precinct wall with a gatehouse; within the wall, a separate house for the abbot or prior; an infirmary (or infirmaries, as some houses had separate accommodation for monks, conversi, and the poor); a guest house; and gardens, orchards and dovecotes (columbaria) to provide for the refectory tables. Dovecotes are especially interesting. These small dome-roofed buildings of circular plan were frequently built very close to the churches, as at Ballybeg, Fore, and Kilcooley—Augustinian, Benedictine, and Cistercian foundations, respectively.