Immunization

Vaccination has virtually eradicated many infectious diseases (e.g. polio and diphtheria) and has made smallpox extinct. Immunization may be achieved passively, by administration of an immu-noglobulin preparation, or actively, by vaccination.

Passive immunization

Immunoglobulin, prepared from pooled plasma, may provide short-term protection against infections, such as measles, if given after exposure. This is used for immunocompromised individuals exposed to specific infections. It is also used to protect patients with congenital immunodeficiency. Specific products are prepared from hyperimmune donors and used for postexposure management (e.g. hepatitis B, varicella zoster and tetanus).

Immunization

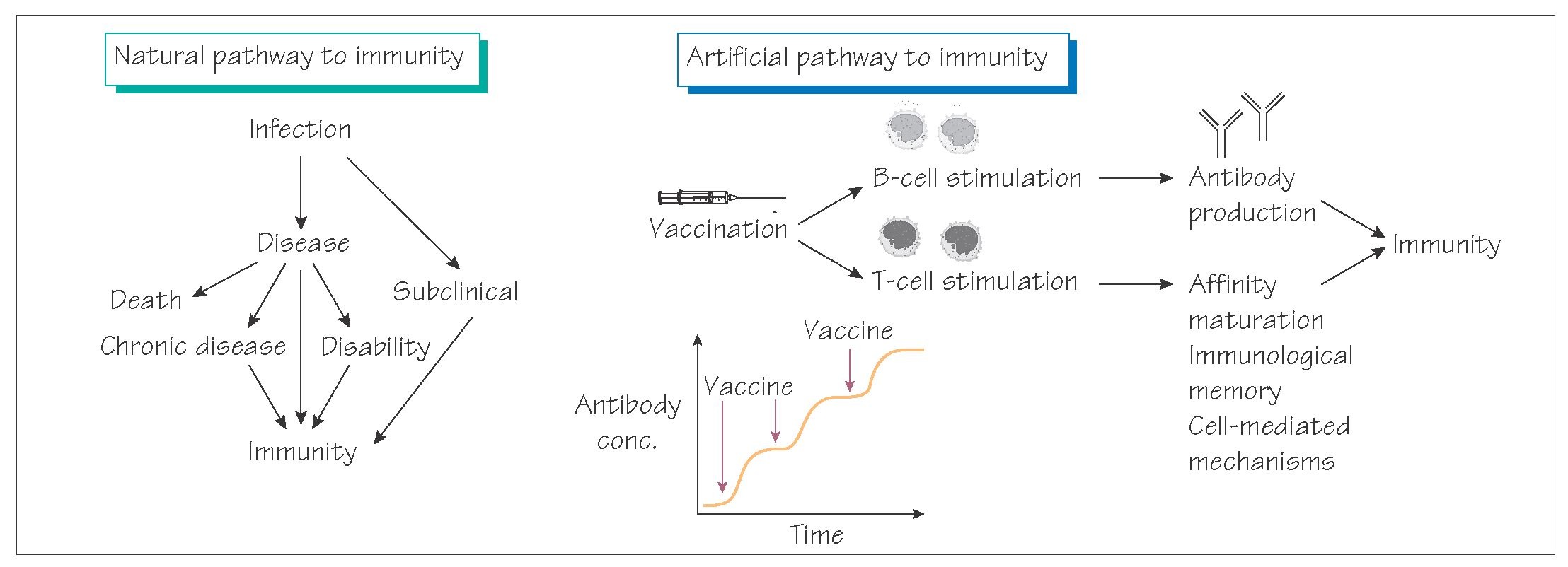

Immunization aims to generate immunity without the complications associated with the natural infection and is achieved by administering a vaccine that generates immunity without harm. There are different types of vaccines.

• Whole organisms (bacteria or viruses, e.g. influenza).

• Isolated antigenic components (acellular, e.g. meningitis C vaccine).

• Live attenuated vaccines that contain strains with reduced/ absent pathogenicity (e.g. MMR). Live vaccines can cause disease in immunocompromised patients and are avoided in pregnancy because of the risk of fetal infection.

• Toxins of tetanus and diphtheria are inactivated (toxoids) so that they are non-toxic but fully immunogenic.

Vaccine immunogenicity can be increased by adding adjuvants or by conjugation with proteins (e.g. against Haemophilus influenzae type b). Genetic engineering can be used to create acellular vaccines safely (e.g. against hepatitis B).

Immunization programmes can be used to eradicate a pathogen (e.g. smallpox, which is complete, and polio, which is nearing completion), but this is only achievable where there is no non- human reservoir of the infection. Elimination can be achieved where for instance the disease has largely disappeared, but the organism remains in humans, animal hosts or the environment (e.g. clinical diphtheria and tetanus). Containment is achieved where the burden of disease or transmission is reduced significantly (e.g. pertussis).

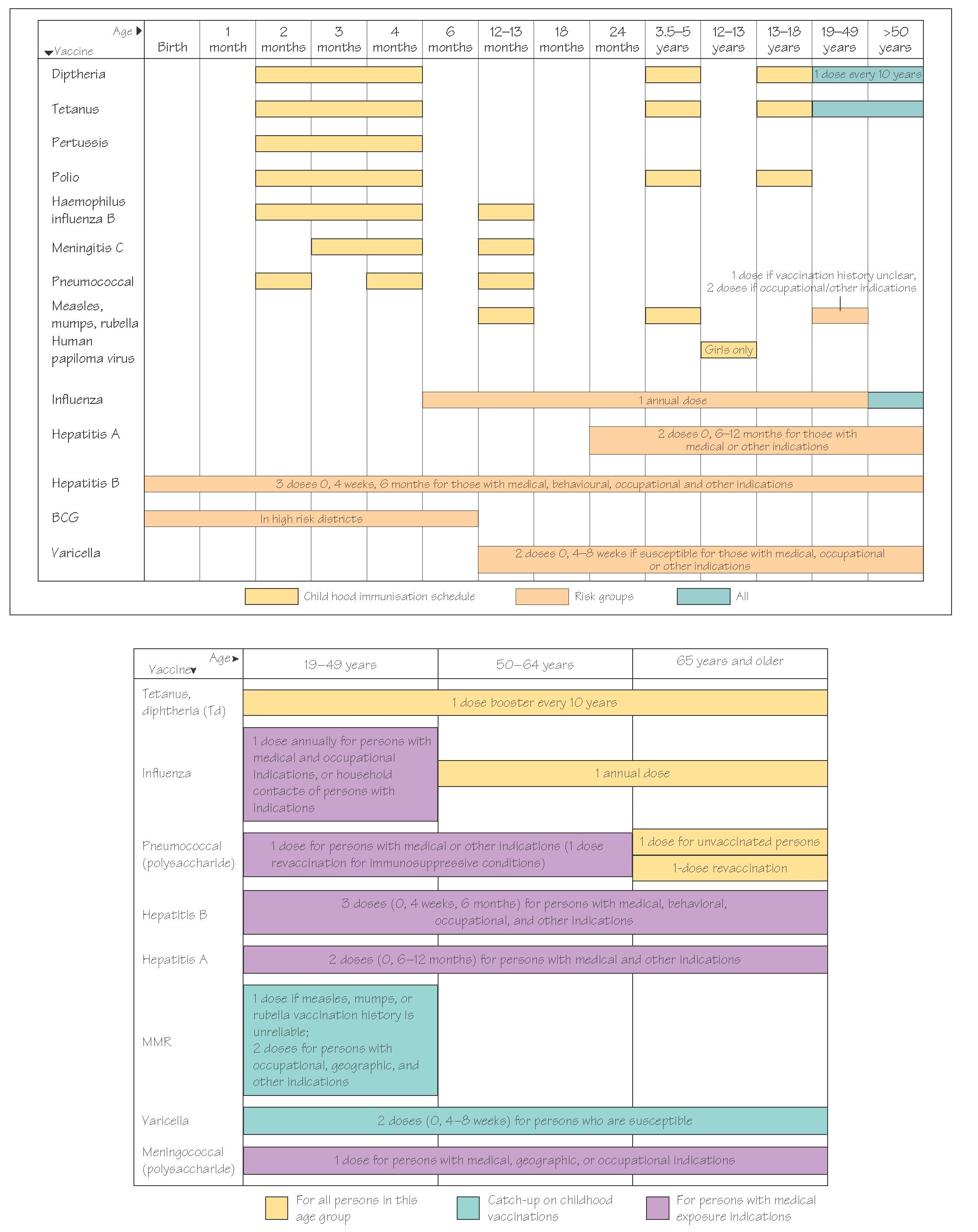

Universal immunization is adopted for most childhood infections (see diagram of vaccination schedules). Selective vaccination is used for those at risk from a disease that is otherwise rare (e.g. hepatitis B in healthcare workers). Immunization programmes are updated regularly to take account of changing disease epidemiology and new vaccine availability.

Vaccine safety

All clinical interventions carry some degree of risk. In determining vaccine policy the risks from the natural disease must significantly outweigh the risks of vaccination. The safety of any vaccine is of paramount importance. Extensive trials are carried out to evaluate safety and strict ‘good manufacturing practice’ legislation governs the production of vaccines. When a vaccine is given, records are kept of the circumstances of administration and the vaccine lot number. A number of highly publicized false vaccine scares have undermined health professional and public confidence in a number of childhood vaccines. This in turn has reduced uptake and resulted in deaths and lifelong morbidity as a consequence of re-emergence of diseases such as whooping cough and measles.

Travellers should take specialized advice about the vaccinations needed for their journeys (e.g. yellow fever vaccine).