Abstract

The medical field in recent years has been facing increasing pressures for lower cost and increased quality of healthcare. These two pressures are forcing dramatic changes throughout the industry. Managing knowledge in healthcare enterprises is hence crucial for optimal achievement of lowered cost of services with higher quality. The following topic focuses on developing and fostering a knowledge management process model. We then look at key barriers for healthcare organizations to cross in order to fully manage knowledge.

introduction

The healthcare industry is information intensive and recent trends in the industry have shown that this fact is being acknowledged (Morrissey, 1995; Desouza, 2001). For instance, doctors use about two million pieces of information to manage their patients (Pauker, Gorry, Kassirer & Schwartz, 1976; Smith, 1996). About a third of doctor’s time is spent recording and combining information and a third of the costs of a healthcare provider are spent on personal and professional communication (Hersch & Lunin, 1995). There are new scientific findings and discoveries taking place every day. It is estimated that medical knowledge increases fourfold during a professional’s lifetime (Heathfield & Louw, 1999), which inevitably means that one cannot practice high quality medicine without constantly updating his or her knowledge. The pressures toward specialization in healthcare are also strong. Unfortunately, the result is that clinicians know more and more about less and less. Hence it becomes difficult for them to manage the many patients whose conditions require skills that cross traditional specialties. To add to this, doctors also face greater demands from their patients. With the recent advances of e-health portals, patients actively search for medical knowledge. Such consumers are increasingly interested in treatment quality issues and are also more aware of the different treatment choices and care possibilities.

Managing knowledge in healthcare enterprises is hence crucial for optimal achievement of lowered cost of services with higher quality. The fact that the medical sector makes up a large proportion of a country’s budget and gross domestic product (GDP), any improvements to help lower cost will lead to significant benefits. For instance, in 1998 the healthcare expenditure in the US was $1.160 billion, which represented 13.6% of the GDP (Sheng, 2000). In this topic, we look at the knowledge management process and its intricacies in healthcare enterprises.

knowledge management process

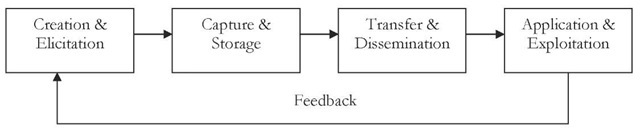

Knowledge management from a process perspective is concerned with the creation, dissemination, and utilization of knowledge in the organization. Therefore, a well-structured process needs to be in place to manage knowledge successfully. The process can be divided into the following steps: beginning with knowledge creation or elicitation, followed by its capture or storage, then transfer or dissemination, and lastly its exploitation. We now elaborate on the various stages of the process:

creation and Elicitation

Knowledge needs to be created and solicited from sources in order to serve as inputs to the knowledge management process. For the first scenario where knowledge has to be created, we begin at the root — data. Relevant data needs to be gathered from various sources such as transaction, sales, billing, and collection systems. Once relevant data is gathered, it needs to be processed to generate meaningful information. Transaction processing systems take care of this task in most businesses today. Just like data, information from various sources needs to be gathered. An important consideration to be aware of is that information can come from external sources in addition to internal sources. Government and industry publications, market surveys, laws and regulations, etc., all make up the external sources. Information once gathered needs to be integrated. Once all necessary information is at our disposal, we can begin analyzing it for patterns, associations, and trends — generating knowledge. The task of knowledge creation can be delegated to dedicated personnel, such as marketing or financial analysts. An alternative would be to employ artificial intelligence-based computing techniques for the task such as genetic algorithms, artificial neural networks, and intelligent agents (Desouza, 2002a). Data mining and knowledge discovery in data bases (KDD) relate to the process of extracting valid, previously unknown and potentially useful patterns and information from raw data in large data bases. The analogy of mining suggests the sifting through of large amounts of low grade ore (data) to find something valuable. It is a multi-step, iterative inductive process. It includes such tasks as: problem analysis, data extraction, data preparation and cleaning, data reduction, rule development, output analysis and review. Because data mining involves retrospective analyses of data, experimental design is outside the scope of data mining. Generally, data mining and KDD are treated as synonyms and refer to the whole process in moving from data to knowledge. The objective of data mining is to extract valuable information from data with the ultimate objective of knowledge discovery.

Figure 1. Knowledge management process

Knowledge also resides in the minds of employees in the form of know-how. Much of the knowledge residing with employees is in tacit form. To enable for sharing across the organization, this knowledge needs to be transferred to explicit format. According to Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), for tacit knowledge to be made explicit there is heavy reliance on figurative language and symbolism. An inviting organizational atmosphere is central for knowledge solicitation. Individuals must be willing to share their know-how with colleagues without fear of personal value loss and low job security. Knowledge management is about sharing. Employees are more likely to communicate freely in an informal atmosphere with peers than when mandated by management. Desouza (2003b) studied knowledge exchange in game rooms of a high-technology company and found significant project-based knowledge exchanged.

capture and storage

To enable distribution and storage, knowledge gathered must be codified in a machine-readable format. Codification of knowledge calls for transfer of explicit knowledge in the form of paper reports or manuals into electronic documents, and tacit knowledge into explicit form first and then to electronic representations. These documents need to have search capabilities to enable ease of knowledge retrieval. The codification strategy is based on the idea that the knowledge can be codified, stored and reused. This means that the knowledge is extracted from the person who developed it, is made independent of that person and reused for various purposes. This approach allows many people to search for and retrieve knowledge without having to contact the person who originally developed it. Codification of knowledge, while being beneficial for distribution purposes, does have associated costs. For instance, it is easier to transfer strategic know-how outside the organization for scrupulous purposes. It is also expensive to codify knowledge and create repositories. We may also witness information overload in which large directories of codified knowledge may never be used due to the overwhelming nature of the information. Codified knowledge has to be gathered from various sources and be made centrally available to all organizational members. Use of centralized repositories facilitates easy and quick retrieval of knowledge, eliminates duplication of efforts at the departmental or organizational levels and hence saves cost. Data warehouses are being employed extensively for storing organizational knowledge (Desouza, 2002a).

Transfer and Dissemination

One of the biggest barriers to organizational knowledge usage is a blocked channel between knowledge provider and seeker. Blockages arise from causes such as temporal location or the lack of incentives for knowledge sharing. Ruggles’ (1998) study of 431 US and European companies shows that “creating networks of knowledge workers” and “mapping internal knowledge” are the two top missions for effective knowledge management.

Proper access and retrieval mechanisms need to be in place to facilitate easy access to knowledge repositories. Today almost all knowledge repositories are being web-enabled to provide for the widest dissemination via the Internet or intranets. Group Support Systems are also being employed to facilitate knowledge sharing, with two of the most prominent being IBM’s Lotus Notes and Microsoft’s Exchange. Security of data sources and user friendliness are important considerations that need to be considered while providing access to knowledge repositories. Use of passwords and secure servers is important when providing access to knowledge of a sensitive nature. Access mechanisms also need to be user-friendly in order to encourage use of knowledge repositories.

Exchange of explicit knowledge is relatively easy via electronic communities. However, exchange of tacit knowledge is easier when we have a shared context, co-location, and common language (verbal or non-verbal cues), as it enables high levels of understanding among organizational members (Brown & Duguid, 1991). Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) identify the processes of socialization and externalization as means of transferring tacit knowledge. Socialization keeps the knowledge tacit during the transfer, whereas externalization changes the tacit knowledge into more explicit knowledge. Examples of socialization include on-the-job training and apprenticeships. Externalization includes the use of metaphors and analogies to trigger dialogue among individuals. Some of the knowledge is, however, lost in the transfer. To foster such knowledge sharing, organizations should allow for video and desktop conferencing as viable alternatives for knowledge dissemination.

Exploitation and Application

Employee usage of knowledge repositories for purposes of organizational performance is a key measure of the system’s success. Knowledge will never turn into innovation unless people learn from it and learn to apply it. The enhanced ability to collect and process data or to communicate electronically does not — on its own — necessarily lead to improved human communication or action (Walsham, 2001). Recently the notion of communities of practice to foster knowledge sharing and exploitation has received widespread attention. Brown and Duguid (1991) argued that a key task for organizations is thus to detect and support existing or emergent communities. Much of knowledge exploitation and application happens in team settings and workgroups in organizations, hence support must be provided. Davis and Botkin (1994) summarize the six traits of a knowledge-based business as follows:

1. The more they (customers) use knowledge-based offerings, the smarter they get.

2. The more you use knowledge-based offerings, the smarter you get.

3. Knowledge-based products and services adjust to changing circumstances.

4. Knowledge-based businesses can customize their offerings.

5. Knowledge-based products and services have relatively short life cycles.

6. Knowledge-based businesses react to customers in real time.

knowledge management in hospitals

We now apply the generic discussion of knowledge, knowledge management, and the process in the context of healthcare enterprises. For purposes of this topic, we focus our attention on hospitals, although much of the discussion can be applied to other healthcare enterprises, such as pharmaceutical companies, insurance providers, etc.

Knowledge in Hospitals

In healthcare, we have the presence of both explicit and tacit forms of knowledge. Explicit knowledge is available in medical journals, research reports, and industry publications. Explicit knowledge can be classified under: internal and external. Internal are those that are relevant to the practice of medicine, such as medical journals and research reports. External are legal, governmental, and other publications that do not directly affect patient treatment methodology but govern general medical practices. Three dimensions in health information outlined by Sorthon, Braithewaite and Lorenzi (1997) include management information, professional information, and patient information. Overlap and commonalties are identified, but fundamental differences exist in the types of information required for each dimension, the way the information is used, and the way standards are maintained. The achievement of a comprehensive and integrated data structure that can serve the multiple needs of each of these three dimensions is the ultimate goal in most healthcare information system development. Tacit knowledge is found in the minds of highly specialized practitioners, such as neurosurgeons or cardiac arrest specialists. Much of tacit knowledge resides in the minds of individuals. Seldom does efficient knowledge sharing take place. One exception to this is where practitioners exchange know-how at industry or academic conferences. This, however, happens on an all-too-infrequent basis.

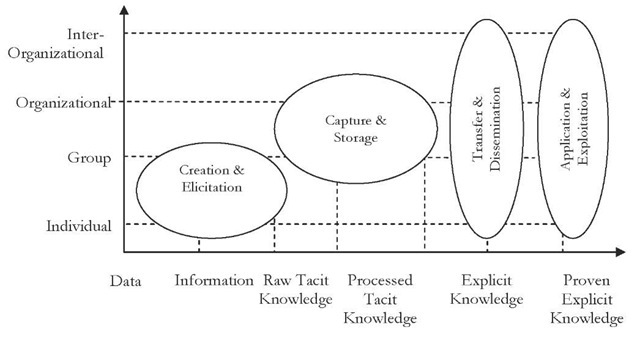

Figure 2. Staged look at knowledge management

Knowledge Management in Hospitals

In the following section we step through the various stages of the knowledge management process.

Knowledge Creation and Elicitation

Creation and elicitation of knowledge can be handled in one of two modes: controlled or free form. In the controlled scenario, we can have an individual department responsible for overseeing knowledge gathering from the various functional areas. This department can be in lieu of the current medical records department in most hospitals, which are responsible for centrally storing patient information. We can also have a variation in which control is divested to each department. In this method, each department will be responsible for coordinating knowledge-sharing efforts from their constituents. For instance, a person in the pharmaceutical department will be responsible for gathering all knowledge on drugs administered to patients. In the second approach, i.e., free form, each individual is responsible for contributing to the organization’s knowledge resource. A strong locus of control is absent. Individuals as end users of organizational resources share equal burden to contribute into the asset. A variation of the free-form strategy can be one in which each group, rather than individuals, are responsible for knowledge creation and sharing. An example would be a group of neurosurgeons that research new knowledge on surgical practices. Each of the above-mentioned strategies has associated pros and cons. For instance, with a controlled strategy, we need to have dedicated individuals responsible for knowledge creation and elicitation from group members. In the free-form strategy, while we do not have the overhead of a dedicated person, we lose a structured knowledge-creation process. Choosing a given strategy is a function of the hospital’s resources. Along with soliciting internal knowledge, a hospital should also acquire relevant knowledge from external entities such as government, regulatory bodies, and research organizations. Gathering of external knowledge is crucial for hospitals due to the high nature of external pressures and their involvement in day-to-day operations.

As portrayed in Figure 2, knowledge creation and elicitation takes place at the individual and group level. Much of the elements gathered at this stage might be raw data, which after processing, becomes information. Information is then applied on experiences, learned associations, and training of employees to generate knowledge. This knowledge remains in tacit form until it is called upon for sharing with peers. Tacit knowledge stored with employees is raw to a large degree, as it is has not been checked for quality or validated against standards.

The other option in the healthcare industry is to generate knowledge through discovery. Data mining and other statistical techniques can be used to sift through large sets of data, and discover hidden patterns, trends, and associations. For instance, in the medical domain all resources are not only very expensive but also scarce. Optimal planning and usage of them is, hence, not a luxury but a requirement. To illustrate this let us take the case of simple blood units. Annually well over 12 million units of blood are transferred to patients (Clare et al., 1995; Goodnough, Soegiarso, Birkmeyer & Welch, 1993) with a cost-per-unit ranging from $48 to $110 with a national average of $78 (Sheng, 2000; Forbes et al., 1991; Hasley, Lave & Kapoor, 1994). Ordering of excess units of blood for operations is the primary cause of waste and corresponding increases in transfusion costs (Jaffray, King & Gillon, 1991). Blood ordered that is not used takes it out of supply for at least 48 hours (Murphy et al., 1995). Even though blood can be returned, it needs to be tested and routed which costs on average $33. In recent years, supply of blood has been decreasing in recent years due to an aging population and increased complexity of screening procedures (Welch, Meehan & Goodnough, 1992). Given these circumstances, any improvements in blood-need prediction can realize significant benefits. Data mining techniques such as artificial neural networks have been employed to sift through large medical databases and generate predictive models which can better forecast blood transfusion requirements. Kraft, Desouza and Androwich (2002a, 2002b, 2003a, 2003b) examine the discovery of knowledge for patient length-of-stay prediction in the Veterans Administration Hospitals. Once such knowledge is generated, it can be made available to external sources.

Knowledge Capture and Storage

Once gathered, knowledge needs to be captured and stored to allow for dissemination and transfer. Two strategies are common for capture and storage: codification and personalization. The codification strategy is based on the idea that knowledge can be codified, stored and reused. This means that the knowledge is extracted from the person who developed it, is made independent of that person and reused for various purposes. This approach allows many people to search for and retrieve knowledge without having to contact the person who originally developed it (Hansen et al., 1999). Organizations that apply the personalization strategy focus on dialogue between individuals, not knowledge objects in a database. To make the personalization strategies work, organizations invest heavily in building networks or communities of people. Knowledge is shared not only face-to-face, but also by e-mail, over the phone and via videoconferences. In the medical domain, the codification strategy is often emphasized, because clinical knowledge is fundamentally the same from doctor to doctor. For instance, the treatment of an ankle sprain is the same in London as in New York or Tokyo. Hence it is easy for clinical knowledge to be captured via codification and to be reused throughout the organization.

Knowledge capture has been one of the most cumbersome tasks for hospitals. Until rather recently much of the patient knowledge was stored in the form of paper reports and charts. Moreover, the knowledge was dispersed throughout the hospital without any order or structure. Knowledge was also recorded in different formats, which made summarization and storage difficult.

Recently we have seen advancements in the technology of Electronic Medical Records (EMRs). EMRs are an attempt to translate information from paper records into a computerized format. Research is also underway for EMRs to include online imagery and video feeds. At the present time they contain patients’ histories, family histories, risk factors, vital signs, test results, etc. (Committee on Maintaining Privacy and Security in Healthcare Applications of the National Information Infrastructure, 1997). EMRs offer several advantages over paper-based records, such as ease of capture and storage. Once in electronic format, the documents seldom need to be put through additional transformations prior to their storage.

Tacit knowledge also needs to be captured and stored at this stage. This takes place in multiple stages. First, individuals must share their tacit know-how with members of a group. During this period, discussions and dialogue take place in which members of a group validate raw tacit knowledge and new perspectives are sought. Once validated, tacit knowledge is then made explicit through capture in electronic documents such as reports, meeting minutes, etc., and is then stored in the knowledge repositories. Use of data warehouses is common for knowledge storage. Most data warehouses do have web-enabled front-ends to allow for optimal access.

Knowledge Transfer and Dissemination

Knowledge in the hospital once stored centrally needs to be made available for access by the various organizational members. In this manner knowledge assets are leveraged via diffusion throughout the organization. One of the biggest considerations here is security. Only authorized personnel should be able to view authorized knowledge. Techniques such as the use of multiple levels of passwords and other security mechanisms are common. However, organizational security measures also need to be in place. Once the authorized users get hold of the knowledge, care should be taken while using such knowledge, to avoid unscrupulous practices. Moreover, employees need to be encouraged to follow basic security practices, such as changing passwords on a frequent basis, destroying sensitive information once used, etc. Ensuring security is a multi-step process. First, the individual attempting to access information needs to be authenticated. This can be handled through use of passwords, pins, etc. Once authenticated, proper access controls need to be in place. These ensure that a user views only information for which he or she has permission. Moreover, physical security should also be ensured for computer equipment such as servers and printers to prevent unauthorized access and theft.

Disseminating healthcare information and knowledge to members outside the organization also needs to be handled with care. Primarily physicians, clinics, and hospitals that provide optimal care to the patients use health information. Secondary users include insurance companies, managed care providers, pharmaceutical companies, marketing firms, academic researchers, etc. Currently no universal standard is in place to govern exchange of healthcare knowledge among industry partners. Hence, free flow of healthcare knowledge can be assumed to a large degree. From a security perspective, encryption technologies should be used while exchanging knowledge over digital networks. Various forms are available such as public and private key encryptions, digital certificates, virtual private networks, etc. These ensure that only the desired recipient has access to the knowledge. An important consideration while exchanging knowledge with external entities is to ensure that patient identifying information is removed or disguised. One common mechanism is to scramble sensitive information such as social security numbers, last and first names. Another consideration is to ensure proper use by partners. Knowledge transferred outside the organization (i.e., the hospital) can be considered to be of highest quality as it is validated multiple times prior to transmittal.

Medical data needs to be readily accessible and should be used instantaneously (Schaff, Wasserman, Englebrecht & Scholz, 1987). The importance of knowledge management cannot be stressed enough. One aspect of medical knowledge is that different people need different views of the data. Let us take the case of a nurse, for instance. He or she may not be concerned with the intricacies of the patient’s condition, while the surgeon performing the operation will. A pharmacist may only need to know the history of medicine usage and any allergic reactions, in comparison to a radiologist who cares about which area needs to be x-rayed. Hence, the knowledge management system must be flexible to provide different data views to the various users. The use of intelligent agents can play an important role here through customization of user views. Each specialist can deploy customized intelligent agents to go into the knowledge repository and pull out information that concerns them, thus avoiding the information overload syndrome. This will help the various specialists attend to problems more efficiently instead of being drowned with a lot of unnecessary data. Another dimension of knowledge management is the burden put on specialists. A neurosurgeon is paid twice as much, if not more, than a nurse. Hence, we should utilize their skills carefully to get the most productivity. Expert systems play a crucial role here in codifying expertise/knowledge. When a patient comes for treatment, preliminary test and diagnosis should be handled at the front level. Expert systems help by providing a consultation environment whereby nurses and other support staff can diagnose illness and handle basic care, instead of involving senior-level doctors and specialists. This allows for the patients that need the care of experts to receive it and also improves employee morale through less stress.

Knowledge Application and Exploitation

The last stage, and the most important, is the application and exploitation of knowledge resources. Only when knowledge stored is used for clinical decision-making does the asset provide value. As illustrated in Figure3, knowledge application and exploitation should take place at all levels from the individual to inter-organizational efforts. We draw a distinction here between application and exploitation. Applications are predefined routines for which knowledge needs are well defined and can be programmed. For instance, basic diagnosis when a patient first enters the hospitals, these efforts include calculation on blood pressure, pulse rates, etc. Knowledge needed at this level is well defined and to a large extent is repetitive. On the other hand, exploitation calls for using knowledge resources on an ad-hoc basis for random decisionmaking scenarios. For instance, if a hospital wants to devise an optimal nurse scheduling plan, use of current scheduling routines, plus knowledge on each individual’s skill sets can be exploited for devising the optimal schedule. Decisions like these, once handled, seldom repeat themselves on a frequent basis.

With knowledge management being made easy and effective, quality of service can only increase. A nurse, when performing preliminary tests on a patient, can provide them with better information on health issues through consultation with an expert system. Primary care doctors normally refer patients for hospital care. Some of the primary care doctors may work for the hospital (Network) and the rest are independent of the hospital (Out-of-Network). Today there are a lot of inefficiencies associated with referring patients to hospitals. If a patient is referred, he or she has to contact the hospital personnel who then first take in all patient information and then schedule an appointment. The normal wait time can be any where from one to four weeks depending on seriousness. With the Internet revolution today, all patients, doctors, and hospitals can improve the process tremendously through the deployment of dedicated intelligent agents. Each doctor can be provided with a log-on and password to the hospital’s web site. Upon entry to the web site, the doctor can use search agents to browse through appointment schedules, availability of medical resources, etc. These agents can then schedule appointments directly and electronically receive all documentation needed. Hospitals within a certain location can set up independent networks monitored by agents whereby exchange of medical knowledge and resources can take place. Patients can use search agents to browse through hospital web sites, request prescriptions, learn about medical treatments, view frequently asked questions, etc. Intelligent agents can also be trained to learn patient characteristics. Once this takes place, they can be deployed to monitor various medical web sites and send relevant information to the patient in the form of e-mails. Expert systems can be deployed to help the user navigate through the various knowledge bases through recommendations. If a user chooses the main category of “common cold,” the expert system can ask for symptoms, suggest medications, etc. Patients can then use these notifications to improve the quality of their health. Intelligent agents also help in improving quality of service through providing only relevant decision-making information. Personnel can then act quickly and reduce time lags. An added benefit of a successful knowledge management system is less burden and stress on personnel. Hospitals are characterized for being highly stressful and always “on pins and needles” when it comes to employees. Through artificial intelligence, much of the routine details can be automated. This reduces the burden on personnel. Also, specialists and highly valued personnel can concentrate efforts on selected matters, the rest can be handled byjunior level staff and intelligent systems. This makes for a more welcoming atmosphere.

Impending barriers to knowledge management

The medical field has to overcome a few hurdles in order to realize the potential benefits of open connectivity for knowledge sharing among the partners of the supply chain and internal personnel such as doctors, surgeons, nurses, etc. We now highlight three of the most prominent issues:

Unified Medical Vocabulary

The first barrier is the development of a unified medical vocabulary. Without a unified vocabulary, knowledge sharing becomes close to impossible. There is diversity of vocabulary used by medical professionals, which is a problem for information retrieval (Lindberg, Humphreys & McCray, 1993). There are also differences in terminology used by various biomedical specialties, researchers, academics, and variations in information accessing systems, etc. (Houston, 2000). To make matters more complex, expertise among users of medical information also varies significantly. A researcher in neuroscience may use precise terminology from the field, whereas a general practitioner may not. Medical information also must be classified differently based on tasks. Researchers may need information summarized according to categories, while a practitioner or doctor may need patient-specific details that are accurate (Forman, 1995).

To help bridge some of the gap in terminology, we have two main medical thesauri in use. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) are meta-thesauri developed by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) (Desouza, 2001). UMLS was developed in 1986 and has four main components: meta-thesaurus, specialist lexicon, semantic net, and information sources map. The meta-thesaurus is the largest and most complex component incorporating 589,000 names for 235,000 concepts from more than 30 vocabularies, thesauri, etc. (Lindberg et al., 1993). Approaches to organizing terms include human indexing and keyword search, statistical and semantic approaches. Human indexing is ineffective as different experts use varying concepts to classify documents, plus it is time-consuming for large volumes of data. The probability of two people using the same term to classify a document is less than 20% (Furnas, Landauer, Gomez & Dumais, 1987). Also different users use different terms when searching for documents. Artificial Intelligence-based techniques are making headway in the field of information retrieval. Houston et al. (2000) used a Hopfield network to help in designing retrieval mechanism for the CANCERLIT study. The issue of standardization of terminology continues to be a great debate. The Healthcare Financing Association (HCFA) is adopting some Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) standards to bring conformity to data (Moynihan, 1996). We can expect more standards to be released in the next few years to enable sharing of data.

security and privacy concerns

With sharing of data comes the inherent risk of manipulation and security issues. Security of patients’ data and preventing it from entering the wrong hands are big concerns in the field (Pretzer, 1996). Strict controls need to be put in place before open connectivity can take place. Patients’ data are truly personal and any manipulation or unauthorized dissemination has grave consequences. Sharing ofpatient-identifiable data between members of the healthcare supply chain members is receiving serious scrutiny currently. Government and other regulatory bodies will need to set up proper laws to help administer data transmission and security (Palmer et al., 1986). The recent Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPPA) Act can be seen as one of many governmental interventions into the healthcare industry for the protection of consumer privacy rights. Enterprises will have to go to the basics of ethics and operate carefully.

organizational culture

In every organization we can see the application of the 20/80 rule. Knowledge providers make up 20% of the workforce, as they possess experiences and insights that are beneficial to the organization. The remaining 80% are consumers of this knowledge (Desouza, 2002a). The providers are often reluctant to share and transfer knowledge as they fear doing so will make them less powerful or less valuable to the organization (Desouza, 2003a, 2003b). Between departments we also find knowledge barriers, in which one group may not want to share insights collected with the other. To help alleviate some of these issues, management should strive to provide incentives and rewards for knowledge-sharing practices. A highly successful approach is to tie a portion of one’s compensation to group and company performance, thus motivating employees to share knowledge to ensure better overall company performance. Additionally, Foucault (1977) noted the inseparability of knowledge and power, in the sense that what we know affects how influential we are, and vice versa our status affects whether what we know is considered important. Hence, to alleviate this concern, an enterprise-wide initiative should be carried out making any knowledge repository accessible to all employees without regard to which department or group generated it.

A key dimension of organizational culture is leadership. A study conducted by Andersen and APQC revealed that one crucial reason why organizations are unable to effectively leverage knowledge is because of a lack of commitment of top leadership to sharing organizational knowledge or there are too few role models who exhibit the desired behavior (Hiebeler, 1996). Studies have shown that knowledge management responsibilities normally fall with middle managers, as they have to prove its worth to top-level executives. This is a good and bad thing. It is a good thing because normally middle-level managers act as liaisons between employees and top-level management, hence they are best suited to lead the revolution due to their experience with both frontline, as well as higher-level authorities. On the other hand it is negative, as top-level management does not consider it important to devote higher-level personnel for the task. This is changing, however. Some large companies are beginning to create the position of chief knowledge officer, which in time will become a necessity for all organizations. A successful knowledge officer must have a broad understanding of the company’s operation and be able to energize the organization to embrace the knowledge revolution (Desouza & Raider, 2003). Some of the responsibilities must include setting up knowledge management strategies and tactics, gaining senior management support, fostering organizational learning, and hiring required personnel.

It is quite conceivable that healthcare enterprises will start creating the positions of chief knowledge officers and knowledge champions. Top management involvement and support for knowledge management initiatives cannot be underestimated. This is of pivotal importance in hospitals, as their key competitive asset is medical knowledge.

conclusions

Some researchers and practitioners have expressed concern about knowledge management being a mere fad (Desouza, 2003b). To deliver promised values, knowledge management must address strategic issues and provide for competitive advantages in enterprises. McDermott (1999) noted that companies soon find that solely relying on the use of information technology to leverage organizational knowledge seldom works. The following topic has introduced knowledge management and its process. We have also applied it to healthcare enterprises focusing on hospitals. Finally, we justified the knowledge management process by looking through two main strategic frameworks.

Knowledge management initiatives are well underway in most healthcare enterprises, and we can expect the number and significance of such efforts to increase over the next few years. Areas of future and continued research include: automated search and retrieval techniques for healthcare information, intelligent patient monitoring systems, and optimal knowledge representation semantics.