Of the three primary “internal” arts of China, xingyiquan (also spelled hsing i ch’uan and shing yi ch’uan) is the most visibly martial and the least well known and understood in the West. Xingyiquan (Form Will Fist) is a complex art, utilizing bare-handed and weapon techniques, that applies more linear and angular force than the other two internal arts of baguazhang (pa kua ch’uan) and taijiquan (tai chi ch’uan). Xingyi is probably best known for its emphasis on extraordinary power applied explosively. Several styles or lineages of xingyi exist, named for the various provinces in China where they were developed. Xingyi has been practiced widely in China, and the styles are not limited to the province for which they are named. For example, Shifu (Master) Kenny Gong reports that he learned the Hebei style along with bone medicine as a child in Canton.

The origins of xingyiquan are traditionally assigned to General Yue Fei, who is believed to have developed the boxing system from the movements of the spear during the Song dynasty (920-1127). According to legend, he developed both xingyi and Eagle Claw, the former for his officers, the latter for his troops. Tradition asserts that his teachings were passed down secretly and in a topic now lost until a wandering Daoist (Taoist) taught xingyiquan to General Ji Jike (also called Ji Longfeng; 1600-1660) and gave him a copy of Yue Fei’s topic. Of Ji Jike’s students, two are important: Ma Xueli of the Henan province and Cao Jiwu of the Shanxi province. Cao Jiwu was not only Feng’s foremost disciple, but also a commanding officer of the army in the Shanxi province, and he trained his officers in xingyiquan. From Cao Jiwu, the Shanxi or Orthodox style of xingyi descends. Tradition holds that Ma Xueli originally became a servant in Feng’s household, where he secretly watched the xingyi class. He learned so well that he was later formally accepted, and from him descends the Henan school. The Henan style has become closely associated with Chinese Moslems and has lost some of the ties to Daoist cosmology seen in the other styles.

Two students at the Shen Wu Academy of Martial Arts in Garden Grove, California, hone their xingyiquan skills.

Cao Jiwu had a disciple named Dai Longbang who had previously been a taijiquan master. He trained his two sons, who introduced him to a farmer named Li Luoneng (Li Lao Nan). Li Luoneng studied for ten years and took xingyi back to his home province of Hebei. In the Hebei province, xingyi-quan absorbed some of the local techniques of another boxing system, baguazhang, to become the Hebei style. Two stories exist of how this occurred. The more colorful one is that a Dong Haichuan, the founder of baguazhang, fought Li Luoneng’s top student, Guo Yunshen, for three days, with neither being able to win. Impressed with each other’s techniques, they began cross-training their students in the two arts. More probable is the story that many masters of both systems lived in this province, and many became friends—especially bagua’s Cheng Tinghua and xingyi’s Li Cunyi. From these friendships, cross-training occurred and the Hebei style developed.

The Yiquan (I Ch’uan) school derives from Guo Yunshen’s student and kinsman, Wang Xiangzhai. His style places a great emphasis on static meditation while in a standing position. During World War II, Wang defeated several Japanese swordsmen and judoka (practitioners of judo). When invited, Wang turned down an opportunity to teach his art in Japan. However, one of his opponents, Kenichi Sawai, later became his student and introduced Wang’s style of xingyi into Japan as Taiki-Ken.

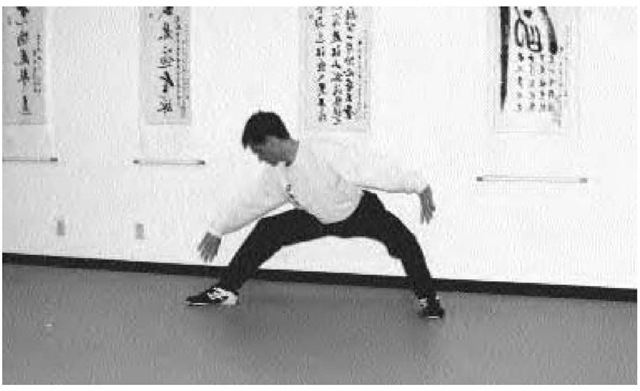

A student practices xingyiquan at the Shen Wu Academy of Martial Arts in Garden Grove, California.

Training in xingyi consists of a series of standing meditations (called “standing stake”), stretching and conditioning exercises sometimes called qigong (chi kung), a series of forms, and one- and two-man drills. The Shanxi, Hebei, and Yiquan systems share the five basic fists (beng quan [crushing fist], pi [chopping], pao [pounding], zuan [drilling], and heng [crossing]), which are named for the elements of Daoist cosmology: wood, metal, fire, water, and earth.

There are also twelve animals upon which forms are based in these styles: dragon, tiger, bear, eagle, horse, ostrich, alligator, hawk, chicken, sparrow, snake, and monkey. Because the names represent Chinese characters, the names of some of the animals may change between styles and even from teacher to teacher. For example, alligator may be called snapping turtle or water dragon, and ostrich may be called tai bird, crane, or phoenix. Some styles combine the bear and eagle into one bear-eagle form. In general, the Shanxi styles have the most complicated animal sets and the most weapon forms, while the Yiquan styles are the simplest. Henan style, which has been practiced extensively among Chinese Moslems, is the simplest, in that it does not use the five elemental fists and its animal forms are based on only ten animals. The animal forms are also very short, consisting of one or two moves each.

Weapons used in xingyi include the spear (often considered the archetypal xingyi weapon), the staff, the double-edged sword, the cutlass or broadsword, needles, and the halberd. In addition, a Hebei stylist will also learn the basics of bagua, including forms called “walking the circle” and the “Eight Palms Form.”

Training normally starts by learning the basic standing exercises, starting with the fundamental stance, called san ti (three essentials). This develops posture and alignment. The basic exercises (dragon turns head, looking at moon in sea, boa waves head, lion plays with ball, and the turning exercise) are taught next to introduce the student to proper body movement. The five fists are then taught, introducing the student to the concepts of generating power in various directions. After that, the student is introduced to other exercises and the forms. Three one-man forms are taught: the Five Element Linking Form, the Twelve Animal Form, and the assorted form. Several two-man forms also exist and may be part of the training: These include Two Hand Cannon, the Conquering Cycle Form, and others.

Many exercises and drills exist to help the student learn these techniques and applications involving striking; throwing and grappling are also learned from the forms. Shifu Kenny Gong of the Hebei style asserts that xingyiquan has three special attributes: the ability to sense and take an opponent’s root, or balance (“cut the root”), to act and strike instantly (“baby catches butterfly”), and to stun an opponent with a shout (“thunder voice”). The first two are said to give the xingyi practitioner the look of not fighting when he fights. The third ability is reputedly lost to the current generation.