Wrestling or grappling is the nucleus for Chinese bare-handed martial arts, going back to the dawn of Chinese civilization. It has consisted of various forms and been called by different names over the centuries based on changing times, China’s vast geographical setting, and multiethnic society. From earliest times it was a basic military combat skill that complemented weapons techniques.

Chinese wrestling’s mythological origins are found in the fight between the Yellow Emperor and Chi You, the inventor of weapons. Chi You’s followers are said to have donned animal-horn headdresses to butt their opponents in hand-to-hand combat. Thus, one of the earliest names for wrestling was juedi (horn butting). Another early term, used as a verb, bo (to seize or strike), to describe bare-handed fighting, including wrestling, was apparently also used as a noun to describe boxing. Thus, we can see the complementary relationship between Chinese wrestling and boxing, which, in earliest times, were likely barely distinguishable.

During the Spring and Autumn period (770-476 b.c.), exceptional wrestlers were selected to serve as bodyguards to accompany field commanders in their chariots. This tradition is vividly portrayed centuries later in the powerful guardian figures associated with Buddhist art.

In the Record of Rituals (second century b.c.), wrestling, termed jueli (compare strength), is described, along with archery, as a major element of military training carried out during the winter months after the harvest. During the Qin period (221-207 b.c.), wrestling (juedi, the accepted formal name) was officially designated as the ceremonial military sport.

During the Former Han period (206-208 b.c.), wrestling and boxing (shoubo [hand striking]) became more clearly distinguishable, the former more of a sport emphasizing holds and throws, and the latter retaining the deadlier, no-holds-barred, hand-to-hand combat skills. However, wrestling’s full evolution as a sport with rules and limits was uneven. The official Tang History (a.D. 618-960) mentions wrestling matches held in the imperial palace in which heads were smashed, arms broken, and blood flowed freely.

Another trend discernible during the Former Han was the exchange of martial arts skills between China and the nomadic peoples to the north. One of Han emperor Wu’s (140-87 b.c.) bodyguards, Jin Ridi, a Xiongnu (ancestors of the Mongols), used a skill called shuaihu (a neck-lock throw) to defeat a would-be assassin. A similar term, shuaijiao (leg throw), ultimately became the modern common name for Chinese wrestling. This was also likely the period when both Chinese boxing (shoubo) and wrestling (juedi) were introduced to the Korean peninsula through military colonies established and maintained as far south as Pyongyang between 108 b.c. and a.d. 313. These were the terms used for bare-handed Korean military martial arts throughout the Koryo period (918-1392) and into the following early Yi period.

Wrestling tournaments were grand occasions for both commoners and the elite. Folk matches drew crowds from many miles around, while imperial tournaments were accompanied by much pomp, with rows of military drummers on either side of the wrestling ring. Tang emperor Zhuang Zong (924-926) personally challenged his guests and offered prizes if they could beat him. One individual defeated him and was made governor of a prefecture.

Some of what we know about wrestling can be found in the Record of Wrestling (Jueli Ji, ca. 960), the very existence of which is testimony to the role of wrestling in Chinese popular culture. In addition to the older terms, juedi and jueli, it lists several later terms, including xiangpu, a colloquial form for popular folk wrestling (the term first appears between a.d. 265 and 316); the term adopted in Japan for sumo; and xiangfei, a local term used in Sichuan and Hebei.

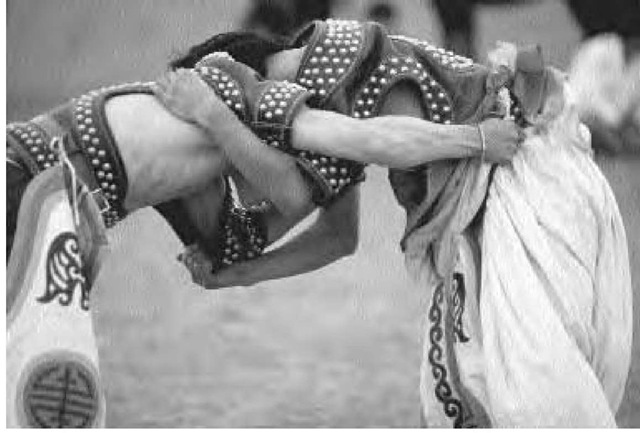

Two Mongolian wrestlers lock themselves in battle during a match in China.

Contemporary descriptions of society in the Song dynasty (960-1279) capitals of Kaifeng and Hangzhou reveal that wrestling enjoyed widespread popularity. Wrestling associations were among the specialty groups abounding in the capital of Hangzhou. Open-air matches were held at specially designated areas in and around the city, sometimes in spacious temple grounds. People came from all around to watch and participate. The wrestlers included both men and women, and there were even mixed male-female matches, such as the one described in the novel Water Margin (also known as All Men Are Brothers or Outlaws of the Marsh). In this episode, a woman, Woman Duan Number Three, confronts Wang Qing. Wang fools her and flips her to the ground, but immediately snatches her up with a move called “Tiger Embraces His Head.”

The scholar-official Sima Guang, in a memorial to court (1062), opposed the spectacle of scantily clad women wrestlers. Moreover, the elite palace guards or Inner Group were all top-flight wrestlers.

The Mongols, who ruled China from 1271 to 1368, emphasized the “men’s three competitive skills” of riding, archery, and wrestling. They were key elements tested in competition for leadership positions. To say that these were only men’s skills, however, is somewhat misleading, for women also practiced them. The Travels of Marco Polo describes one instance where the daughter of King Kaidu (grandson of Ogodai) agreed to marry any man who could best her in wrestling. But, much to the dismay of her family and other well-wishers, she took her skill seriously, defeated all hopefuls, and remained single. The Mongols prohibited Han Chinese martial arts practices, which by this time consisted mainly of boxing and weapons routines.

Like the Mongols, the Manchus, who ruled China between 1644 and 1911, stressed riding, archery, and wrestling. They too attempted to place restrictions on Han Chinese martial arts practices, which they associated with subversive activities. Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722) is said to have established an elite Expert Wrestlers Banner (Shanpu Ying) to reward the strongmen/bodyguards he used to keep palace intrigues in check. Manchu emperors actively encouraged wrestling, called buku, among their own people and used it as a political and diplomatic tool in their relations with the Mongols. The Tibetans were also fond of wrestling, and this activity is depicted in a wall mural in the Potala Palace.

The main objective of Chinese wrestling, regardless of local variations of style (such as Beijing, Baoding, Tianjin, or Mongolian), is to throw the opponent to the ground by a combination of seizing, and arm maneuvers (twists and turns) and leg maneuvers (sweeps and hooks). A rough-and-tumble folk sport, it was practiced under Spartan conditions, without mats, and wrestlers practiced rolling in a fetal position to lessen the impact from hitting the ground.

In the turmoil following in the wake of the Communist rise to power in China and finally the split between the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan in 1949, a number of Chinese wrestling masters immigrated to Taiwan. Among them was shuaijiao (or, as it is more commonly spelled in the West, shuai-chiao) champion Chang Tung-sheng. Chang and his students were instrumental in popularizing the system outside of Asia.

Chinese wrestling was popularized in the twentieth century as sport shuaijiao. The modern form is a type of jacketed wrestling, although practitioners assert that throwing in shuaijiao does not depend on grabbing the opponent’s jacket or clothing. The priority is to grab the muscle and bone through the clothing in order to control and throw down the opponent. However, the use of the competitor’s heavy quilted, short-sleeved jacket, which wraps tightly around the torso and is tied with a canvas belt, adds variety to the techniques used in controlling and throwing the opponent. Fast footwork using sweeps, inner hooks, and kicks to the opponent’s legs are combined with the use of the arms to control and strike in order to create a two-directional action, making a powerful throw.

There is no mat or groundwork in shuaijiao. After the opponent is thrown to the ground, one strives to maintain the superior standing position. This is particularly the case against a larger opponent, who because of greater body weight will generally have the advantage in grappling on the ground. In a self-defense situation, after the opponent is thrown a shuaijiao, the practitioner immediately applies a joint lock and executes hand strikes or kicks with the knee or foot to vital areas of the falling or downed opponent.

Modern shuaijiao training utilizes individual drills, work with partners, and exercises employing apparatus. Balance, flexibility, strength, and body awareness are developed through movement such as hand and foot drills. After attaining proficiency in solo drills, the trainee advances to work with a partner. Practicing with a partner allows one to add power and coordination to techniques. Drills against full-speed punches, kicks, and grappling attacks are practiced to aid in training for san-shou (Chinese freestyle kickboxing) and self-defense. For the inexperienced novice student to learn, remember, and deploy martial art techniques quickly, while difficult in training, becomes more so under stress. In order to teach effective physical applications of shuaijiao techniques, free sparring drills and related mock-physical-encounter situations are of paramount importance in the training. Work with various types of equipment (striking and kicking the heavy bag, weight training, and work with canvas bags filled with steel shot) supplements the solo and partner practice of techniques.

Contemporary shuaijiao utilizes a ranking system divided into ten levels. The first version of the ranking system was created by Grand Master Chang Tung-sheng for the Central Police College of Taiwan. The ranking system follows the Japanese model of beginner (chieh) levels in descending order of fifth through first to expert (teng) levels of first through tenth. A colored belt signifying rank is worn with the uniform. The current ranking system was developed by Chang and Chi-hsiu D. Weng and is recognized by the International Shuai-chiao Association and the United States Shuai-chiao Association.

Shuaijiao has developed an international following. In the United States, the United States Shuai-chiao Association oversees the activities of the system, and in the spring of 2000 the Pan-American Shuai-chiao Federation was established in Sao Paulo, Brazil. The first Pan-American Shuai-chiao tournament was held in the following year.