The South Pacific islands (Hawaii, Samoa, New Zealand, Guam, and Tahiti) were inhabited, before the arrival of Europeans and the decimation of much of the native population, by peoples who were united by a common group of languages, the Polynesian languages. Examples of these languages include Hawaiian, Samoan, Maori, and Tahitian. The technology level of the Pacific islanders was not advanced, never progressing beyond late Paleolithic technology. The islanders did not have the use of metals or metalsmithing techniques. As a result, when one discusses martial arts among these peoples, unarmed combat techniques and fighting with wooden weapons become paramount, and there did exist several unique weapons native only to these islands.

The peoples of the Pacific islands were the world’s first long-distance navigators. Beginning from their homes in Asia, these peoples spread, by outrigger canoe, to islands throughout the South Pacific, including Easter Island (Rapa Nui), the most remote place on earth. By the 1500s, these islands were completely colonized by the Polynesians. Although navigation and commerce broke down between these islands for reasons that are still unknown, the very act of reaching these farthest outposts of land indicates the bravery of these peoples, which, to no great surprise, was often reflected in their fighting arts.

The oral traditions of these islands tell of a long history of warriors accomplished in martial arts. The reasons for the necessity to know how to fight are many, but it can be surmised that given the scarce resources and population pressures of a limited physical area, such as these islands, the competition for these resources must have been fierce. It is therefore not surprising that different tribes or clans of peoples would have had to know how to fight well to survive during times when population pressures would have led to brutal warfare. These oral histories probably reflect the fighting skills of those exceptional warriors who were able to prevail in such a climate.

An example of the scarce resources and demand for warriors is documented through the colonization of Easter Island and the eventual ruin of the society established there. After the island was colonized by Polynesians, the inhabitants channeled their energies into building great representations of their gods after warfare became too destructive. Unfortunately, the sublimated behavior of building these figures used up most of the natural resources of the island. The islanders entered a new phase of their existence when it was apparent that no new figures could be constructed. They developed a ritual event. Once a year a contest was held to see who could swim the shark-infested seas to one of the smaller islands and return with a bird’s egg. The winner then helped select the chief. Even this eventually placed a strain on the resources of the island, and by the time Easter Island was “discovered” by the Europeans, the Rapa Nui culture was once again on the road to intra-island warfare due to population pressures and lack of technology. Warriors in this culture were revered as individuals who could help a group survive during these bloody times. Unfortunately, little is known about the actual fighting arts of the Pacific islanders. The colonization of the islands by the Europeans was marked by events that not only decimated the populations of these islands, but in so doing destroyed their cultures. So complete was this destruction that today, long after the European colonization of the Hawaiian islands, fewer than 10 percent of native Hawaiians can speak their own language.

The Europeans who contacted and later settled these islands also brought with them diseases, such as smallpox, for which the native populations had no immunity. Just as destructive to the natives, the invaders also brought with them a zeal to convert the “heathens” to the “correct” paths of Western religious traditions. These factors, combined with the awe many native peoples felt for the overwhelming technical superiority of the Europeans, led to the loss of many native art forms. Without a doubt, martial art traditions must be included in this list.

The native arsenal relied heavily on the wood and stone that were found on the islands. Most Pacific islands were young in terms of geological age (Hawaii still contains more active volcanoes than any other American state), so a wide variety of stones were readily available for use in the construction of knives, daggers, and spear points. The variety of hard woods available on the islands also led to the creation of superior fighting staves and sticks. It is not surprising, therefore, that the use of the knife, spear, and staff weapons became critical for the armed martial arts of these islands.

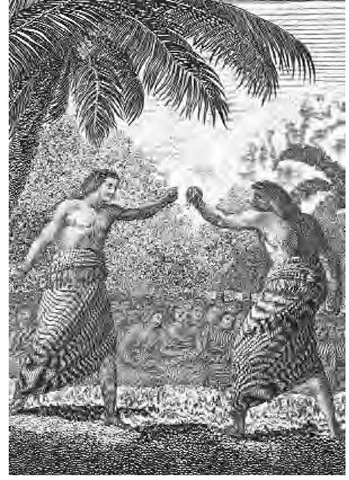

A late-nineteenth-century engraving by J.W. Warren of a bare-knuckle boxing match between Hapae islanders.

Two staff weapons deserve special mention due to their uniqueness and lethality. The Maori, the aboriginal peoples of New Zealand, developed a special type of massive war club. With a length of about 1.5 meters and a weight of approximately 5 kilograms, this curved, two-handed club was powerful enough to shatter the largest bones in a human body. Maori warriors were able to close against the British invaders and use the weapon to good effect. Another type of club, used by the Samoans, was the tewha-tewha, a long stick (1.5 meters) with a wooden haft at its end. This axlike device was also a fierce weapon in a premetal technology.

Even in this Neolithic world, an extensive range of unique weapons was developed for self-defense by these ingenious peoples. For example, lacking metal to construct swords, the Pacific islanders nevertheless developed the tebutje. These “swords” were made from long clubs inlaid with shark’s teeth. The teeth constituted excellent cutting edges against an opponent. The fighting arts for these weapons have since become extinct, but this leaves intriguing room to speculate on how they were used and how effective the tebutje was in combat.

The combat systems of Polynesia were centered on these and similar weapons. They also included a great deal of hand-to-hand combat. What few oral histories remain from these islands tell of warriors trained in striking with both the hands and feet and in wrestling, and possessing an impressive knowledge of human anatomy. The struggles and warfare between the islanders would have necessitated such a development in martial arts.

Perhaps the most well-documented martial arts from these islands are from Hawaii. They were among the last to be settled by the European colonizers, and to a great extent, the Hawaiians were able to keep their independence until 1893, longer than most other South Sea island nations. The islands themselves were united only in the early 1800s by King Kame-hameha I. Until this time, warfare between the Hawaiians was common, which led to the development and practice of both armed and unarmed combat. Unfortunately, once again because of the destruction of native Hawaiian culture, even descriptions of these martial arts are scarce.

One of the best-known examples of Hawaiian martial arts is the unarmed combat art of Lua, which is close to extinction today. The word translates as “the art of bone-breaking.” It might be compared to the art of koppo in traditional Japanese martial arts. Due to the lack of written historical records among the Hawaiians, a preliterate people, there is no accurate way of dating just how long this fighting system existed.

Lua was a hand-to-hand system of combat that emphasized the use of a knowledge of anatomy to strike the weak points of the human body. Expert practitioners were expected to have the ability to injure or even kill an opponent with such strikes. The techniques that were practiced included the arts of dislocating the fingers and toes, striking to nerve cavities, and hitting and kicking muscles in such a way as to inflict paralysis. Lua was intended as a self-defense art; in its purest form it was not to be considered a sport. Demonstrations of Lua to the general public were forbidden, as it was an art for warriors only.

Among the arts encompassed by Lua were the specific art of bone-breaking, also known as hakihaki, kicking (peku), wrestling (hakoko), and combat with the bare hands (kui). Hawaiian warriors were expected to become proficient in all aspects of the art. In addition to these martial skills,

Lua practitioners were taught the art of massage (lomilomi) and a Hawaiian game of strategy known as konane. In this respect, it can be surmised that the education of a Hawaiian warrior was similar in many ways to the education of Japanese bushi (warriors) and European knights, who were expected to master both the martial arts of self-defense and the civilian arts of refinement.

Lua systems included a form of ritualized combat that is common in other martial arts as well. Ritualized combat, known as kata in Japanese systems and hyung in Korean systems, consists of forms of prearranged movement that teach the practitioner how to punch, kick, throw, and move effectively. These forms existed in European combat systems as well; the Greeks used to practice a type of war dance to train their warriors for combat. These forms are practiced individually or in groups, and the practitioner uses them to develop, among other skills, timing, balance, and technique. The Hawaiian version of this was called the hula. Although this word today conjures up a Hawaiian dance for tourists, evidence indicates that the word also has the older meaning of “war dance.” Indeed, tourists to Hawaii can see Lua movements demonstrated in hula dances during the shows displayed for travelers.

The importance of the hula was critical for developing Lua skills. Warriors were expected to practice the hula daily, not only as a form of exercise but also for developing individual and group martial abilities. There existed both single hula and hula for multiple persons, where groups of warriors would practice the same movements together. This helped to create groups of warriors who could fight together, even if they did not always use the same movements simultaneously.

The practice of Lua was not always confined to the battlefield. There are some accounts that suggest that Lua practitioners would sometimes test their skills on unwary travelers who attended a celebration unaware of the danger that faced them. When the visitor was completely relaxed by the surroundings, the Lua practitioners would strike.

Using their knowledge of human anatomy, the Lua practitioners would dislocate joints and break the bones of the victim. This was done to test the practitioner’s knowledge of his skills, apparently in the belief that these arts had to be put to an actual test to demonstrate the practitioner’s ability. Some victims were resuscitated and allowed to go, but others were left to die after the Lua practitioner was through. On the Hawaiian islands, as on many of the other Pacific islands, the ability to protect oneself was held in high regard, and the need to perfect this ability was paramount, sometimes even more important than the lives of strangers.

In addition to the unarmed combat systems listed above, Hawaiians were taught weapons skills. Weapons that were available to the native Hawaiians included one-handed spears (ihe), a dagger made from wood (pahoa), a short club (newa), a two-handed club (la-au-palau), the sling (maa), and a cord that was used for strangulation (kaane). Lua could therefore be considered a complete martial arts system, covering both weaponry and unarmed combat.

There also existed sportive forms of Hawaiian martial arts that were presented before crowds of onlookers, unlike Lua. Hawaiian-style boxing, known as mokomoko (from the verb moko, “to fight with the fists”), was practiced and demonstrated during religious festivals. From descriptions of the art, mokomoko was apparently a form of bare-fist fighting where the closed fist was used as the exclusive offensive weapon. This Hawaiian boxing differed profoundly from Western styles.

From accounts given by eyewitnesses, the participants were not allowed to block their opponents’ punches with anything other than their own closed fist. This type of deflection is not used in Western or Asian martial arts. In addition, mokomoko combatants would evade their opponents’ blows by either retreating or moving the body out of the way. All blows were aimed for the face, and the person who was the first to fall to the ground was the loser. It was a contest that was designed to test the abilities of the contestants to persevere despite extreme consequences.

It is also important to note that these boxing matches occurred during the season of Makahiki, the Hawaiian New Year. The Hawaiian pantheon contained a multitude of deities, and during this time of the year the god Makahiki was worshipped. Therefore, these Hawaiian sporting events may be considered analogous to other combinations of ritual with sport, such as the Olympic games of the ancient Greeks, who organized those games to honor Zeus, the father of the gods who dwelt on Mount Olympus.

Reports of the outcome of mokomoko contests state that the combat was brutal and the competitors could expect no mercy. Those who did fall to the ground after being defeated were screamed at by the spectators, shouting the phrase, “Eat chicken shit!” Western observers noted that even the winners of matches would have bloody and broken noses, bruises around the eye sockets, and bloody lips. It was not uncommon for teeth to be lost. Participants who excelled in the sport would probably have hands that had become callused and hardened from the repeated blows they inflicted and had inflicted on them. The danger of developing arthritis in the hands, of course, also proportionally increased.

Hawaiians practiced other types of martial disciplines as well. An example is the art of wrestling, hakoko, mentioned earlier. The exact parameters of this wrestling style, or styles, are unknown. From the few remaining descriptions of the art, it seems to have been a sportive as well as combative form of wresting. For the sport variant, the opponent would signal defeat and the match would end. Since this form of wrestling was also displayed during the Makahiki ceremonies, it is also a form of sacred wrestling (wrestling for religious purposes). In any case, the descriptions of the art also state that injuries were common, just as in boxing. Competitors expected danger.

Other martial disciplines that apparently were practiced by the ancient Hawaiians included the art of arrow cutting. This art, known as yadomajutsu in Japan, was a series of techniques that taught the practitioner to deflect arrows, spears, and javelins that were targeted at his person. Skilled practitioners of this art could face multiple projectiles and have the ability to dodge and deflect them without injury.

One of the best practitioners of this art was the greatest king in Hawaiian history: King Kamehameha I. As indicated earlier, this individual was responsible for the unification of the islands, which occurred just prior to European colonization. Hawaiian oral legends tell of Kamehameha dodging twelve spears thrown simultaneously at him. Even if this is an exaggeration, it signifies the importance of this skill in Hawaiian warrior society.

The survival of Polynesian martial arts following the arrival of Europeans was, as noted, very difficult. Firearms took away a great deal of the necessity for hand-to-hand combat, and disease and cultural genocide took its toll. There presently exist some modern forms of Polynesian unarmed combat, most notably the system of lima-lama, which is translated as “hands of wisdom.” The direct origin of this art is unknown. Most, if not all, of the weapons systems that marked Polynesian armed combat have disappeared.

Polynesian martial arts encompassed the arts of self-defense, but were used for sport and religious purposes also. In this respect, they formed a complete martial arts system that was practiced by peoples over a large area of the globe. The lack of metal did not hamper the development of these arts. Rather, the arts grew around the materials that were available. In this respect, like many martial arts, the Polynesian arts were representative of a particular time and culture, which allowed them to flourish and develop.

The martial arts of the South Pacific islanders have, unfortunately, been lost to history. A shadow of them can still be seen in the traditional dances performed for tourists, but these only reflect dimly what was once a proud and unique history. The rediscovery of various forms of martial arts is currently under way; therefore, the possibilities of a rebirth of Polynesian arts cannot be discounted. In this respect, perhaps the future of Polynesian martial arts will be brighter than their recent past.