The Middle East consists of Egypt and the Arab nations to the east of Israel, Turkey, and Iran; and of the North African countries of Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Libya, and the Sudan. Although the following comments are limited to these nations, the boundaries of the Middle East may be extended into other nations such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Cyprus as well. The rise of Islam and the domination of much of the area by the Arab Muslims beginning in the seventh century a.d. bound together the various groups of the region under the banner of Islam. Later, the Ottoman Empire in the thirteenth century further expanded and confirmed the Muslim character of the region under militant Islamic leadership.

Ancient Egypt during the Middle Kingdom (2040-1785 b.c.) offers the earliest convincing evidence of systematic martial arts development, not only in the Middle East, but in recorded history. Painted on the walls of the tombs of Beni Hassan are pairs engaged in grappling maneuvers (some of which are as sophisticated as any used in modern Olympic competition), boxing (including the use of protective equipment such as a forerunner of modern protective headgear), kicking, and stickfighting. The stickfighting techniques have been preserved into the present as tahteeb (a martial art system using sticks and swords). The system continues to be practiced in the religious schools of the Ikhwaan-al-Muslimeen (Muslim Brotherhood). The Bedouin continued until the modern era to utilize a staff in a combat art called naboud. Practice is reported to involve spinning, dancelike forms with the weapon. Similar whirling dances are associated with other martial practice in the region, as well as with the mystical sect of Islam called Su-fism. In addition, the Egyptians developed two-handed spears that could be wielded as lances, shields, and specialized weapons such as the khopesh, a sword that could be used to disarm opponents.

At about the same time, the oldest surviving work of literature, the Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh, portrayed the semidivine protagonist as a wrestler. In this work, Gilgamesh employed his grappling skills to subdue the wild man, Enkidu, who then swore allegiance and became his ally in future battles. The central character is reputed to be based on an historical Sumerian king (ca. 2850 b.c.); therefore, it is interesting that Enkidu specifically accedes to Gilgamesh’s right to rule. Thus, although the epic offers no detailed description of grappling in the second millennium b.c., it may reflect a principle of “war by champions” that prevailed in the area around this time.

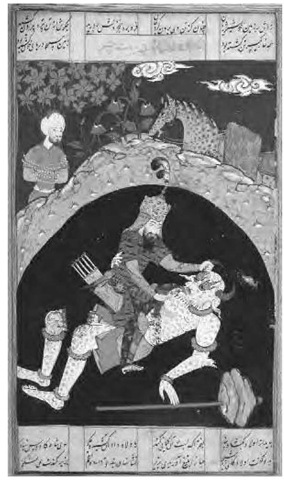

An Indian copy done in Persian style from an Islamic topic depicts Rustan, a seventh-century Persian general, slaying White Deity.

Somewhat later (ca. 1000 b.c.), Semitic tribes could exercise the option of substituting single combat between champions in the place of massed battles. The most famous of these is likely to be the battle between David representing the Hebrews and Goliath of the Philistines, as described in the Bible (1 Samuel). Even closer to the Gilgamesh archetype is the story of Muhammad’s wrestling match with the skeptical sheikh, Rukana ibn ‘Abdu Yazid, as a demonstration of the power of his revelations from God. The Prophet succeeded in his opponent’s conversion after scoring his second fall.

As previously noted, after the initial Arab Muslim conquests of the Middle East, the Ottoman Turks extended the boundaries of the Islamic world and consolidated to a large degree the identity of the Middle East, at least into the twentieth century. The ghazis were a prime force behind the Ottoman expansion. The Ghazi Brotherhoods are of particular relevance to martial history. Members of the Ghazi Brotherhood were roughly comparable to the European knights who were their contemporaries. They were bound by a code of virtue within a democratic organization, and in contrast to the European knight, whose worth eventually became bound to ancestry and rank, the brother was judged on the merits of his own character (e.g., valor, piety) rather than by his wealth or lineage. Brothers were most often followers of Sufism, the mystical sect of Islam that gave rise to the dervishes, whose whirling dances were mentioned above. This dervish influence may have been pervasive in the Ottoman training regimen, given the fact that vigorous dancing even extended to the military training of Janissaries (Christians who either had rejected their faith or had been branded as holding heretical beliefs, who served in the Turkish army) from the fourteenth century, continuing until their dissolution in the nineteenth century. To return to the ghazis, however, they were sworn to the militant expansion of Islam. With the spread of the faith came the dissemination of Turkish martial traditions. Among the most lasting of these traditions has been wrestling.

Turkey is a nation with a long history of wrestling excellence. Turkish tribes originated in Asia, probably somewhere between the Ural Mountains, the Caucasus, and the Caspian Sea. To the east were the Mongols; Turkish contact was primarily with the Huns and the Tatars. Apparently, however, they brought with them many wrestling techniques in their migrations westward, possibly influenced by shuaijiao (shuai-chiao) and other sources of Chinese and Mongolian wrestling. Turkey was overrun by the Persians in the sixth century b.c., remained under Persian domination until the invasion of Alexander (334 b.c.), and was a part of the Roman Empire (through the Byzantine period) until the eleventh-century invasions of the Seljuk Turks. Even today, in the former “Turkish” republics of the former Soviet Union, such as Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan, local wrestling traditions influenced by both classical European and Asian styles survive among the local populations and nomads. History provides various glimpses of Turkish wrestling, and gymnasiums for wrestlers (tekke) began to appear by the fifteenth century.

Alireza Dabir of Iran waves his country’s flag after winning the gold medal for freestyle wrestling at the Sydney Olympics, October 1, 2000.

Today, Turkish wrestling, known as Yagli-Gures, is one of the nation’s most popular sports, and there is evidence that this is a form related to Persian/Iranian koshti. Similarities abound. Wrestlers wear trousers only; they otherwise are naked and do not wear shoes. Turkish wrestling is unique in that the competitors, known as pehlivans, oil themselves down completely before a match. Note that the name pehlivan resembles the term for traditional Iranian wrestlers (pahlavani). The foregoing characteristics argue for a strong link between this system and Iranian systems, as do many of the techniques.

The oil obviously makes it much more difficult to grab an opponent, and competitors must rely on a great deal of skill to throw or take down a wrestler. Grabbing and holding onto the pants, known as a kispet, is allowed in Yagli. Both holds and throws are allowed in the sport; the match continues until one concedes defeat or a referee stops the match to ensure a wrestler’s safety. The lack of a time limit can make for grueling competitions. In 1969, a national championship match lasted for fourteen and a half hours. The Turkish wrestling techniques are essentially those of modern freestyle. For example, techniques include the sarma, known in contemporary wrestling as a “grapevine” hold. The sport is now growing on the European continent, started by Turks who migrated from Turkey, but now including participants from other nationalities as well.

Iranian (formerly Persian) wrestling is a second major grappling tradition of the Middle East. Known for much of its history as Persia, Iran is an ancient nation, with civilizations in this region extending as far back as 2000 b.c. Certainly by the seventh century b.c., Persian civilization had reached one of the many high points of its power and was building itself into an empire that covered much of the Middle East and North Africa. Iranians themselves incorporated wrestling techniques into their warrior skills, and there are accounts of Greek wrestlers and pankration experts challenging these wrestlers as the two cultures met, and ultimately clashed with, each other. Martial arts academies developed as well, known as Varzesh-e-Pahlavani. From these sources, Iran developed its own unique system of wrestling, koshti. Koshti apparently had both combat and sport aspects, and koshti exponents were trained to use the system as an unarmed battlefield art when necessary. With the Islamic invasions of the seventh and eighth centuries a.d., and with Islamic discouragement of practices that were considered pagan, koshti apparently fell into unpopularity.

Iranian wrestling systems apparently employed all the aspects of Greek wrestling. Although the systems seemed to lack any emphasis on striking, koshti exponents used throws, takedowns, and trips, as well as arm and leg locks and choke holds. Practitioners were expected to be able to disarm weaponed opponents when necessary as well. It is likely that in sport competitions, many of the more dangerous holds were not allowed. Practitioners would compete in trousers, naked from the waist up. In many respects, koshti, in all of its variants, may be compared to many Western systems of wrestling and to jujutsu from Japan.

Centuries later, however, the Iranian Shah Ismail “the Great,” after making himself shah, made the Shiite Twelver sect of Islam (believers in the twelve descendants of their spiritual leader Ali, Muhammad’s son-in-law) the state religion in Azerbaijan and Iran. He was noted for the persecution of Sunnism and the suppression of non-Safawid Sufism. As a consequence, the Safawid Brotherhood (a Sufi brotherhood whose sheiks claimed descent from Muhammad’s son-in-law, Ali) maintained considerable military and political power. This fact may have led to Ismail’s patronage of martial arts.

He was noted for his promotion of the Zour Khaneh, or Zur Khane (House of Strength). A contemporary description (written in 1962) notes that there was in the center of the mosquelike building an octagonal pit, 15 feet in diameter, lined in blue tile, but filled with earth. Beyond the pit lay weight-lifting apparatus, and on the wall hung a portrait of Ali. Training featured preliminary rhythmic calisthenics, followed immediately by whirling dances accompanied by bells, drums, gongs, and passages sung from the Shahnama (the great Persian epic the topic of Kings). This form of training bears clear connections to Sufi practices that incorporate both song and whirling dances into worship—as well as suggesting analogies to a vast cross-cultural range of martial dances/exercises. In addition to the more contemporary apparatus, traditional devices (dating back at least to Ismail’s reign) are used in the Zour Khaneh. These exercise tools are essentially oversized weapons (for example, the kadabeh, an iron bow with a chain bowstring) that are brandished during the training dances. In addition to these conditioning exercises, the trainees at the Zour Khaneh practice koshti.

In the middle of the twentieth century, as Iran sought to enter the modern world, traditional Iranian arts such as koshti were replaced by modern wrestling systems such as the Olympic types of Greco-Roman and freestyle. With the Islamic Revolution in 1979, whose adherents view all pre-Islamic practices as pagan, any current prospects for development of koshti are not bright. Iranians have excelled at modern wrestling competitions, however, reflecting the long and distinguished history of wrestling that exists in this nation.

Finally, the Middle East has produced at least one contemporary combat system, as well: krav maga. Krav maga (Hebrew; contact combat) is an Israeli martial art that was developed in the 1940s for use by the Israeli military and intelligence services. The creator of the system was Imi Lichtenfeld, an immigrant to Israel from Bratislava, Slovak (formerly Czechoslovakia). Today it is the official fighting art of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) and has gained popularity worldwide as an effective and devastating fighting method. It is a fighting art exclusively; sport variants do not exist. Krav maga techniques are designed to be simple and direct. High kicks are used sparingly in the art; kicks are directed at waist level or below. Knee strikes, especially against the groin and inner thigh area, are especially used. Practitioners also use kicks against the legs, similar to those used in Muay Thai (Thai kick-boxing), to unbalance an opponent. Punches are based on boxing moves and are intended for vital points or to place the mass of the body behind a blow to gain punching power. Open-hand techniques to the eyes, ears, throat, and solar plexus are used. Elbow techniques are used extensively.

These techniques require little strength but have devastating results; an elbow strike to the face or floating ribs can easily disable an opponent. Throwing techniques are not the type usually seen in judo or sambo; they have more in common with freestyle wrestling takedowns. Krav maga has been called the “first unarmed combat system of the twentieth century.” This is meant to convey the fact that it developed in the twentieth century with the understanding and awareness of modern combat. Firearms were the weapons of choice for twentieth-century warriors, as they are for those of the twenty-first century, and terrorism and sudden violence often define the battlefield in the modern world.

The martial arts systems of the Middle East are a unique chapter in the fighting skills of the world. This area is the cradle of civilization, so it is no great surprise that many of the first fighting arts were practiced here as well. Since many trade routes existed through these regions, it is also not surprising that the techniques and styles from various civilizations can be seen. In this respect, perhaps the fighting arts of the Middle East are among the most eclectic in the world.