The martial arts, like all areas of human endeavor, have developed folklore (materials that are learned as an element of the common experience in a special interest group, which could be based on ethnicity, avocation, gender, among other factors) as an integral element of their core knowledge. In fact, by virtue of the secrecy and exclusively oral transmission inherent in most traditions, martial arts communities provide especially favorable conditions for the development of folklore. The most highly developed folk genres in the martial arts fall into three principal categories: myth, legend, and folk belief. The first two genres often focus on origins and include tales ranging from those concerning the origins of war and weapons in general to the origins of specific styles of martial arts. The third type tends to focus on the qualities of particular arts and, in general, articulates relationships between fighting systems and larger belief systems (e.g., religion, medicine).

Myths are narratives set in an environment predating the present state of the cosmos. The world and its features remain malleable. The present order and laws of cause and effect have not yet been set into motion. The actors in such narratives tend to be gods, demons, or semidivine ancestors. Myth characteristically concerns itself with basic principles (the ordering of the seasons, the creation of moral codes).

Legends, on the other hand, are set in the historical reality of the group, are populated by human (though often exceptional) characters, and focus on more mundane issues. In many cases, these narratives are based to some degree on historically verifiable individuals. Although the events described may be extraordinary, they never cross the line into actions that are implausible to group members.

Folk belief may be cast in narrative form, may exist as a succinct statement of belief, or may survive simply as allusions to elements of the common knowledge of the group (i.e., as traditional axioms). Finally, the label “folk” should not serve as a prejudicial comment on the validity of the material so labeled. Such elements of expressive culture invariably reflect qualities of self-image and worldview, and thus merit attention.

These materials frequently exist apart from written media (although committing a narrative, for example, to print does not change the folk status of those versions of the tale that continue to circulate by oral or other traditional means). While orally transmitted narratives have the potential for maintaining thematic consistency, factual accuracy in the oral transmission of historical information over long periods of time is rare. Oral tradition tends to force events, figures, and actions into consistency with the worldview of the group and the group’s conventional aesthetic formulas (seen, e.g., in plots, character types, or narrative episodes). Also, since the goal of these genres is rhetorical, not informative, history is manipulated or even constructed in an effort to legitimize the present order.

Moreover, in the martial arts information equates to a kind of power; the purveyor of information controls that power, and others will seek to benefit from it. Some martial arts myths seek to elicit patriotic sympathies or, at a minimum, to identify with familiar popular symbols. One should also keep in mind that some of these myths may be intentionally deceptive and may have a political agenda. Often, the possible motives behind the myths are more fascinating than the myths themselves.

Origin Narratives

Probably the earliest martial arts-related Chinese myth is the story of the origin of war and weapons. This narrative goes back to the legendary founder of Chinese culture, the Yellow Emperor, and one of his officials, Chi You, who rebelled against him. Chi You, China’s ancient God of War, who is said to have invented weapons, is depicted as a semihuman creature with horns and jagged swordlike eyebrows. The story describes the suppression of Chi You’s rebellion and the attaining of ultimate control over the means of force by the Yellow Emperor. Symbolically, it reflects the perpetual conflict between authority and its opponents.

Such mythic narratives substantiate the claims of smaller groups within larger cultures as well. The origin narrative orally perpetuated within Shorinjin-ryu Saito Ninjitsu is representative. Oppressed by raiders, a group of northern Japanese farmers sent a young man to find help. Reaching a sacred valley, he fasted and meditated for twenty-one days, until the Shorinjin (the Immortal Man) appeared and granted him the art of “Ninjitsu Mastery, the ‘Magical Art’” (Phelps 1996, 70). While returning home, he was swept up by tengu (Japanese; mountain demons) who took him to Dai Tengu (king of the Tengu), who bestowed upon him the art of double-spinning Tengu Swordsmanship. He then returned to his village to defeat their enemies by means of the system he had acquired, a system that has been passed down along the Saito family line to the present (Phelps 1996).

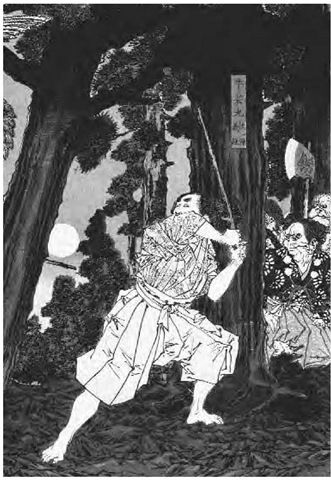

A nineteenth-century depiction of Minamoto no Yoshitsune, a famous and chivalrous warrior, being taught martial arts by the tengu (mountain goblins) on Mount Kurama, outside Kyoto.

Similar narratives of origin ascend the social strata. Although the previous narrative is preserved solely by means of oral tradition, historian Roy Ron notes similar mythic motifs in Japanese sword schools during the Tokugawa period. He observes that the historical documentation of a school’s lineage, along with such information as “the founder’s biography and some historical information relating to the style; often they included legends and myths of sacred secret transmission of knowledge from legendary warriors, supernatural beings, or from the divinities themselves to the founder’s ancestors. Such divine connection provided the school with authority and ‘proof’ of superior skills in an increasingly competitive world of swordsmanship.”

In contrast, legends occur in a more contemporary setting and are often more widely disseminated, as is the story of the Maiden of Yue, a legend that reveals the principles of Chinese martial arts, including yin-yang theory (complementary opposition). It is also part of a larger story of how Gou Jian, king of the state of Yue, sought to strengthen his state by employing the best assets available (including women in this case). As a result he overcame his old opponent, the king of Wu, and became the dominant hegemon at the close of the Spring and Autumn period (496-473 B.C.).

Legends Associated with Locales

Legends of the Shaolin Monastery represent this narrative category well, since the site literally swims in an ocean of greater and lesser myths and legends formed from a core of facts. The monastery is the home of Chinese Chan (Zen) Buddhism, which is said to have been introduced by the Indian monk Bodhidharma around A.D. 525. History further records that thirteen Shaolin monks helped Tang emperor Taizong (given name Li Shimin) overcome a key opponent in founding the Tang dynasty. In the mid-sixteenth century, a form of staff fighting was named for the monastery. Numerous references from this period also cite martial arts practices among the Shaolin monks, and the heroic exploits of some of the monks in campaigns against Japanese pirates during this period brought them lasting fame as the Shaolin Monk Soldiers. These basic shreds of fact provide the raw materials for constructing folk historical narrative.

In discussing the more prominent traditional narratives associated with Shaolin Monastery, it is instructive to address them in the chronological order of their appearance on the stage of history. The earliest of these is the story (recorded ca. 960) of the monk Seng Zhou (ca. 560) who, in his youth, is said to have prayed to a temple guardian figure to help him become strong enough to ward off his bullying fellow acolytes. The guardian figure offers him meat to build his strength. Ironically, while the story is exaggerated, it may reveal something about the actual nature of monastic living during Buddhism’s early years in China, including loose adherence to the vegetarian dietary codes prescribed for Buddhists. Another much later legend (oral and of unknown origin) claims Tang emperor Taizong issued a decree exempting Shaolin monks from the strict Buddhist vegetarian diet because of their assistance in capturing one of the emperor’s opponents (a mix of fact and fiction).

There is only one narrative directly associated with an identifiable Shaolin martial art; this is the story (related on a stone tablet dated ca. 1517) of a kitchen worker who, the tale relates, is said to have transformed himself into a fierce guardian spirit called King Jinnaluo. According to this text, the worker in spirit form scared off a band of marauding Red Turban rebels with his fire-stoking staff and saved the monastery during the turbulence at the end of the Yuan dynasty (ca. 1368). Actually, the monastery is known to have been largely destroyed and to have been abandoned by the monks around this time. Therefore, the story seems to have served a dual purpose: to warn later generations of monks to take their security duties seriously and (possibly) to reinforce the martial image of the place in order to ward off would-be transgressors. In any case, in the mid-sixteenth century, a form of staff fighting was named for the monastery.

The next Shaolin narrative, which appears in Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan, written by the Ming patriot and historian Huang Zongxi in 1669, is wrapped up in the politics of foreign Manchu rule over China. According to this story, the boxing practiced in Shaolin Monastery became known as the External School, in contrast to the Internal School, after the Daoist Zhang Sanfeng (ca. 1125) invented the latter. Here, Internal School opposition to the External School appears to symbolize Chinese resistance to Manchu rule. In the twentieth century, proponents of Yang-style taiji-quan (tai chi ch’uan) adopted Zhang Sanfeng as their patriarch, giving this legend new life.

Migratory Legends

According to at least one of the origin legends circulating in the taijiquan repertoire, one day Zhang Sanfeng witnessed a battle between a crane and a snake, and from the experience he created taiji. It is probably not coincidental that this origin narrative is associated with more than one martial art. For example, Wu Mei (Ng Mui), reputed in legends of the Triad society (originally an anti-Qing, pro-Ming secret society, discussed below) to be one of the Five Elders who escaped following the burning of the Shaolin Monastery by the Qing, was said to have created yongchun (wing chun) boxing after witnessing a battle between a snake and a crane, or in some versions, a snake and a fox. From Sumatra comes the same tale of a fight between a snake and a bird, witnessed by a woman who was then inspired to create Indonesian Silat.

Folklorists label narratives of this sort migratory legends (believed by the folk, set in the historical past, frequently incorporating named legendary figures, yet attached to a variety of persons in different temporal and geographic settings). Among the three possible origins of the tale type—cross-cultural coincidence of events, cross-cultural creations of virtually identical fictions, and an original creation and subsequent borrow-ing—the latter is the most likely explanation.

The animal-modeling motif incorporated into the taiji, yongchun, and silat legends is common among the martial arts. This motif runs the gamut from specific incidents of copying the animal combat pattern, as described above, to the incorporation of general principles from long periods of observation to belief in possession by animal “spirits” in certain Southeast Asian martial arts.

Sometime after 1812, a legend arose with the spread of membership in the Heaven and Earth Society (also known as the Triads or Hong League), a secret society. Associating themselves with the heroic and patriotic image of the Ming-period Shaolin Monk Soldiers, Heaven and Earth Society branches began to trace their origins to a second Shaolin Monastery they claimed was located in Fujian province. According to the story, a group of Shaolin monks, said to have aided Emperor Kangxi to defeat a group of Mongols, became the object of court jealousies and were forced to flee south to Fujian. There, government forces supposedly located and attacked the monks’ secret Southern Shaolin Monastery. Five monks escaped to become the Five Progenitors of the Heaven and Earth Society. Around 1893, a popular knights errant or martial arts novel, Emperor Qianlong Visits the South (also known as Wannian Qing, or Evergreen), further embellished and spread the story. Like such heterodox religious groups as the Eight Trigrams and White Lotus sects, and the Boxers of 1900, secret-society members practiced martial arts. The factors of their involvement in martial arts, the center of their activity being in southern China, and identification with the mythical Southern Shaolin Monastery resulted in a number of the styles they practiced being called Southern Shaolin styles.

The connection of sanctuaries, political resistance, and the clandestine practice of martial arts apparent in these nineteenth-century Chinese legends is a widespread traditional motif. The following two examples suggest its dissemination as well as suggesting that this dissemination is not due to the diffusion of an individual narrative. Korean tradition, Dakin Burdick reports, holds that attempts to ban martial arts practice by the conquering

Japanese led the practice of native arts (many of which were Chinese in origin) to move “to the Buddhist monasteries, a traditional place of refuge for out-of-favor warriors” (1997, 33). Similarly, in the African Brazilian martial culture of capoeira, the traditional oral history of the art ties it to the quilombo (Portuguese; runaway slave settlement) of Palmares. Under the protection of the legendary King Zumbi, capoeira was either created in the bush or retained from African unarmed combat forms (sources differ regarding the origin of the art). Preserved in the same place were major elements of the indigenous African religions, from which were synthesized modern Candomble (a syncretic blend of Roman Catholicism and African religions) and similar New World faiths. Thus, capoeira’s legendary origins are associated with both ethnic conflict and religions of the disenfranchised in a manner reminiscent of the Shaolin traditions.

Traditional texts of this sort should be read as political rhetoric as much as—or perhaps more than—history. As James C. Scott argues, much folk culture amounts to “legitimation, or even celebration” of evasive and cunning forms of resistance (1985, 300). Trickster tales, tales of bandits, peasant heroes, and similar revolutionary items of expressive culture help create a climate of opinion.

Folk Hero Legends

One of the most recently invented and familiar of the Shaolin historical narratives is a story that claims that the Indian monk Bodhidharma, the supposed founder of Chinese Chan (Zen) Buddhism, introduced boxing into the monastery as a form of exercise around A.D. 525. This story first appeared in a popular novel, The Travels of Lao T’san, published as a series in a literary magazine in 1907. This story was quickly picked up by others and spread rapidly through publication in a popular contemporary boxing manual, Secrets of Shaolin Boxing Methods, and the first Chinese physical culture history published in 1919. As a result, it has enjoyed vast oral circulation and is one of the most “sacred” of the narratives shared within Chinese and Chinese-derived martial arts. That this story is clearly a twentieth-century invention is confirmed by writings going back at least 250 years earlier, which mention both Bodhidharma and martial arts but make no connection between the two.

Similarly, several styles of boxing are attributed to the Song-period patriot Yue Fei (1103-1142), who counseled armed opposition against, rather than appeasement of, encroaching Jin tribes and was murdered for his efforts. Yue Fei is known to have trained in archery and spear, two key weapons. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that he also studied boxing, considered the basic foundation for weapons skills other than archery, but we have no proof of this. Not until the Qing, about six centuries later, and a time of opposition to foreign Manchu rule are boxing styles attributed to Yue Fei. The earliest reference is in a xinyiquan (now more commonly known as xingyiquan [hsing i ch'uan], form and mind boxing) manual dated 1751. The preface explains that Yue Fei developed yiquan (mind boxing) from his spear techniques. In fact, key xingyiquan forms do have an affinity to spear techniques, but this is not necessarily unusual, since boxing and weapons techniques were intimately related. Cheng Zongyou, in his Elucidation of Shaolin Staff Methods (ca. 1621), emphasizes this point by describing a number of interrelated boxing and weapons forms.

Local legends attempt to extend the legend to regional figures, thus providing a credible lineage for specific styles of xingyi. For example, narratives of the origin of the Hebei style (also known as the Shanxi-Hebei school) continue to circulate orally as well as in printed form. One narrative, the biography of Li Luoneng (Li Lao Nan), maintains that he originally brought xingyi back to Hebei. Subsequently, the Li Luoneng’s xing-yiquan was combined with baguazhang (pa kua ch’uan) to become the Hebei style. Kevin Menard observes that, within the Hebei system, two explanations of the synthesis exist. More probable is that “many masters of both systems lived in this province, and many became friends—especially bagua’s Cheng Tinghua and xingyi’s Li Cunyi. From these friendships, cross-training occurred, and the Hebei style developed.” More dramatic yet less likely is the legend of an epic three-day battle between Dong Haichuan, who according to tradition founded baguazhang, and Li Luoneng’s top student, Guo (Kuo) Yunshen. According to xingyi tradition the fight ended in a stalemate (Menard). Other versions (circulated primarily among bagua practitioners) end in a decisive victory by Dong on the third day. In either case, each was so impressed with the other’s fighting skills that a pact of brotherhood was sworn between the two systems, which resulted in students of either art being required to learn the other.

During the Qing period, because of its potential anti-Manchu implications, the popular novel Complete Biography of Yue Fei was banned by Emperor Qianlong’s (given name Hong Li) literary inquisition. When the Manchus came to power, they initially called their dynasty the Later Jin, after their ancestors, whom Yue Fei had opposed. Thus, here is another example of the relationship between martial arts practice, patriotism, and rebellion. However, it is not until after Qing rule collapsed in the early twentieth century that styles of boxing actually named after Yue Fei appear.

Another interesting possible allusion to Yue Fei can be found (ca. 1789) in the name of the enigmatic Wang Zongyue (potentially translated as “Wang who honors Yue”), to whom the famous Taijiquan Theory is attributed. Whether or not Wang Zongyue actually wrote this short treatise or whether Wang was the invention of Wu Yuxiang (1812-1880?), whose brother supposedly discovered the treatise in a salt store, remains one of the fascinating uncertainties of modern martial arts history. Suffice it to note here that the term “taijiquan” is only found in the title of the treatise, while the treatise itself is essentially a concise, articulate summary of basic Chinese martial arts theory, not necessarily the preserve of a single style of Chinese boxing.

As noted above, the traditional history of yongchun maintains that this southern Chinese boxing system was invented by a Buddhist nun named Wu Mei (Ng Mui) who had escaped from the Shaolin Temple in Hunan (or in some versions, Fujian) province when it was razed in the eighteenth century after an attack by the dominant forces of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) that officially suppressed the martial arts, particularly among Ming (1368-1644) loyalists. After her escape and as the result of witnessing a fight between a fox (or snake, in some histories) and a crane, Wu Mei created a fighting system capable of defeating the existing martial arts practiced by the Manchu forces and Shaolin defectors. Moreover, owing to its simplicity, it could be learned in a relatively short period of time. The style was transmitted to Yan Yongchun, a young woman whom Wu Mei had protected from an unwanted suitor. The martial art took its name from its creator’s student.

Traditional histories of yongchun (and of other systems that claim ties to it) portray a particularly close connection between yongchun practitioners and the traveling Chinese opera performers known as the “Red Junk” performers after the boats that served as both transportation and living quarters for the troupes. These troupes reportedly served as havens for Ming loyalists involved in the resistance against the Qing rulers and offered refuge to all manner of martial artists.

Incontrovertible historical evidence of the exploits of Bodhidharma, Yue Fei, and Wu Mei has been blurred, if not eradicated, by the passing centuries. Details from the biographies of such figures remain malleable and serve the ends of the groups that pass along their life histories. Recently, arguments have been presented, in fact, that suggest that Wu Mei and Yan Yongchun are fictions into whose biographies have been compressed the more mundane history of a martial art. Such may be the case for many of the folk heroes who predate the contemporary age. Even in the case of twentieth-century figures, traditional patterns emerge.

Japanese karate master Yamaguchi Gogen exemplifies the contemporary martial arts folk hero—particularly within the karate community and especially among students of his own Goju-ryu system. Peter Urban, a leading United States Goju master, has compiled many of the orally circulated tales of Yamaguchi. Typical of these narratives is the tale of Yamaguchi’s captivity in a Chinese prison camp in Manchuria. Urban recounts the oral traditions describing the failure of the captors’ attempts to subdue Yama-guchi’s spirit via conventional means. As a result, he became an inspiration for his comrades and an embarrassment to his guards. Ultimately, Yam-aguchi was thrust into a cage with a hungry tiger. According to Urban, not only did Yamaguchi survive by killing the tiger, he did so in twenty seconds. This story (like similar stories of matches between martial artists and formidable beasts) has been hotly debated. Whether truth or fiction, however, such narratives serve not only to deify individuals (usually founders), but to argue for the superhuman abilities that can be attained by diligent practice of the martial arts. Consequently, these fighting systems are often touted as powerful tools for the salvation of the politically oppressed.

Within the oral traditions of Brazilian capoeira, legends circulate that Zumbi, king of the quilombo (runaway slave colony) of Palmares, successfully led resistance against conquest of his quilombo and recapture of his people by virtue of his skills as a capoeirista. J. Lowell Lewis, in his study of the history and practice of the martial art, notes, however, that these narratives did not appear in the oral tradition until the twentieth century. Thus, while the martial art itself may not have figured in the military resistance by Brazil’s ex-slaves, the contemporary legends argue for ethnic pride within the African Brazilian capoeira community.

Folk Belief

The most prominent boxing styles practiced in southern China appear to emphasize “short hitting”—namely, arm and hand movements as opposed to high kicks and more expansive leg movements. This characteristic, as opposed to the more acrobatic movements of standardized “long boxing,” which was developed from a few of the more spectacular “northern” styles, has resulted in southern styles (called nanquan) being placed in a separate category for nationwide martial arts competitions. The apparent difference is reflected in the popular martial arts aphorism, “Southern fists and Northern legs.” The fictionalizing, in this case, lies in the reasons given for the difference: different north-south geographical characteristics and different body types of northern versus southern Chinese. The main problem with this argument is that it fails to account for the full spectrum of northern styles or the fact that a number of the southern styles are known to have been introduced from the north. It also fails to take into account other historical factors, such as the possibility that southern styles evolved from “short-hitting” techniques introduced for military training by General Qi Jiguang and others during their antipirate campaigns in the south.

Other beliefs focus not on the mechanics of martial arts, but on the internal powers acquired through practice. Within the Indonesian martial art of pentjak silat exists the magical tradition of Kebatinan. The esoteric techniques of the art, it is said, permit practitioners to kill at a distance by the use of magic and to render themselves invulnerable. In Java, it was believed that the supernormal powers conferred by silat (rather than world opinion and United Nations intervention) had forced the Dutch to abandon colonialism there in the aftermath of World War II. Lest it be believed that such traditional beliefs are disappearing under the impact of contemporary Southeast Asian society, however, James Scott reports that when an organization claiming thirty thousand members in Malaysia was banned, among the organization’s offenses were teaching silat and encouraging un-Islamic supernatural practices by use of magical chants and trances.

The beliefs in invulnerability acquired by esoteric martial practice fostered by the Harmonious Fists (the Chinese “Boxers” of the late nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries) represent an immediate analogy to this Southeast Asian phenomenon, but belief in the magical invulnerability engendered by traditional martial arts is not limited to Asia. Brazilian capoeira, many of whose practitioners enhance their physical abilities by simultaneously practicing Candomble (an African-based religion syncretized in Brazil), maintains beliefs in the ability to develop supernormal powers. In addition to the creation of the corpo fechado (Portuguese; closed body) that is impervious to knives or bullets, oral tradition attests to the ability of some capoeiristas to transform into an animal or tree, or even to disappear at will.

Worth noting is the fact that not only are individual martial artists transformed into ethnic folk heroes in instances of political conflict, beliefs in the invulnerability developed by the practice of the martial arts are foregrounded in such contexts, as well. Capoeira, silat, and Chinese boxing have each been reputed to give oppressed people an advantage in colonial situations. Martial resistance and supernatural resistance are not invariably yoked, however. For example, in the late nineteenth century the Native American Ghost Dance led by the Paiute prophet Wovoka promised to cleanse the earth of the white man by ritual means, at least as it was practiced among the tribes of the Great Basin. A contemporary religiously fueled guerilla movement, God’s Army, led by the twelve-year-old Htoo Brothers in Myanmar, manifests no martial arts component in the sense used here. Thus, utilizing magical beliefs embedded in martial arts is common in grassroots rebellions, but not inevitable.

On the other hand, folklore is an inevitable feature of the martial arts. Certainly, these traditions cannot be treated as, strictly speaking, historically or scientifically verifiable. Neither should they be discounted as nonsense, however. The sense they embody is an esoteric one of group identity, a metaphysical sense of the ways in which martial doctrines harmonize with the prevailing belief systems of a culture, and a sense of worldview consistent with the contemporary needs of practitioners.