The term martial arts today typically refers to high-level Asian fighting methods from China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, and, to a lesser extent, Thailand, Burma, Indonesia, India, and Vietnam. This perspective is derived primarily from Western popular culture. The standard view holds that non-Asian contributions to the martial arts have been restricted to sport boxing, savate, Greco-Roman wrestling, and the modern fencing sports of foil, epee, and saber. Not only have substantial and highly sophisticated fighting systems, true martial arts, existed outside Asian contexts, but many survive and others are experiencing a renaissance. Like their Asian counterparts, Western martial arts offer their practitioners both self-defense and personal growth.

Proceeding from a concept of martial arts as formulated systems of fighting that teach the practitioners how to kill or injure an opponent while protecting themselves effectively, these combat systems may employ unarmed techniques or hand weapons (firearms excluded). The term Western martial arts, loosely used in this instance to encompass systems developing outside the greater Asian context, can refer to any martial art system that originated in Europe, the Americas, Russia, and even the Middle East or Central Asia. This entry will primarily focus on the martial arts of Europe, as its title suggests, but will also include arts from other areas that are usually ignored, although they are basically in the Western tradition. Sporting systems (such as boxing, wrestling, and modern fencing) that emphasize the use of safety equipment and intentionally limit the number and kind of techniques in order to be competitively scored are eliminated from consideration.

Although no claims can be made for an unbroken record, historical evidence suggests that Western martial arts have been in existence for at least 5,000 years. The first direct evidence of a high-level unarmed combat system dates to the Egyptian Middle Kingdom (2040-1785 B.C.), where techniques of throws, kicks, punches, and joint locks can be found painted on the walls of the tombs of Beni-Hassan. This is the oldest recorded “text” of unarmed fighting techniques in existence. From the variety of physical maneuvers that are demonstrated, it can be inferred that a high-level system of self-defense and unarmed combat existed in Egypt by this time. In addition, Egyptians clearly had extensive training in armed combat. They developed two-handed spears that could be wielded as lances, created shields to protect their warriors in an age when armor was scarce and expensive, and developed a unique sword, the khopesh, that could be used to disarm opponents. It is not difficult, in retrospect, to see that military and martial prowess was one of the reasons that this great civilization was able to endure for thousands of years.

If one moves forward 2,500 years to the Greek peninsula, martial arts are clearly documented, not only through material artifacts such as painted ceramics, but also by firsthand written accounts of practitioners and observers of these arts. In unarmed combat, the Greeks had boxing, wrestling, and the great ancestor of the “Ultimate Fighting Championship”: the pankration (all powers). Boxing during this era was not limited to blows with the closed fists, but also involved the use of the edge of the hand, kicks, elbows, and knees. Wrestling was not the “Greco-Roman” variant of today, but was divided roughly into three main categories. The first type involved groundwork wherein the participants had to get opponents into a joint lock or hold. In the second variant, the participants had to throw each other to the ground, much as in judo or Chinese wrestling. The third type was a combination of the two. In the pankration, the purpose was to get the opponent to admit defeat by any means possible. The only forbidden techniques were eye-gouging and biting. This meant that practitioners could use punches, kicks, wrestling holds, joint locks and choke holds, and throws in any combination required to insure victory.

The ancient Greeks were famously well trained in the military use of weapons as well. The Greek hoplite warrior received extensive instruction in spear and short sword as well as shield work. History provides us with the results of soldiers well trained in these arts both for single combat and close-order drill. When the Hellenized Macedonian youth Alexander the Great set out in the third century B.C. to conquer the world using improved tactics and soldiers well trained in pankration and the use of sword, shield, and long spear, he very nearly succeeded. Only a revolt from his own soldiers and his final illness prevented him from moving deeper into India and beyond. It would be reasonable to assume that Alexander and his forces, which brought Greek civilization in the areas of warfare, mathematics, architecture, sculpture, music, and cuisine through out the conquered territories of Asia, also would have spread their formidable martial culture.

Even more is known about the martial arts of the Roman Empire than about those of the Greeks. Indeed, it is from Latin that we even have our term martial arts—from the “arts of Mars,” Roman god of war. From the disciplined training of the legionnaires to the brutal displays of professional gladiators, Romans displayed their martial prowess. In addition to adopting the skills and methods of the Greeks, they developed many of their own. Their use of logistics and applied engineering resulted in the most formidable war machine of the ancient world. Romans of all classes were also adept at knife fighting, both for personal safety and as a badge of honor. Intriguing hints of gladiator training with blunt or wooden weapons and of their battles between armed and unarmed opponents as well as the specialty of combat with animals suggest a complex repertoire of combat techniques. Speculation exists that some elements of such methods are reflected in the surviving manuals of medieval Italian Masters of Defence.

The decline of Roman civilization in the West and the rise of the feudal kingdoms of the Middle Ages did not halt the development of martial arts in Europe. In the period after the fall of the empire, powerful Germanic and Celtic warrior tribes prospered. These include many notorious for their martial spirits, such as the Gauls, Vandals, Goths, Picts, Angles, Jutes, Saxons, Franks, Lombards, Flems, Norse, Danes, Moors, and the Orthodox Christian warriors of the Byzantine Empire. The medieval warrior was a product of the cultural synthesis between the ordered might of the Roman war machine and the savage dynamism of Germano-Celtic tribes.

The feudal knight of the Middle Ages was to become the very embodiment of the highest martial skill in Western Europe. Medieval warrior cultures were highly trained in the use of a vast array of weaponry. They drilled in and innovated different combinations of arms and armor: assorted shields and bucklers, short-swords and great-swords, axes, maces, staffs, daggers, the longbow and crossbow, as well as flails and war-hammers designed to smash the metal armor of opponents, and an array of deadly bladed pole weapons that assisted in the downfall of the armored knight.

The formidable use of the shield, a highly versatile and effective weapon in its own right, reached its pinnacle in Western Europe. Shield design was in constant refinement. A multitude of specialized shield designs, for use on foot and in mounted combat as well as joust, siege, and single duel, were developed during the Middle Ages.

During the medieval period, masters-at-arms were known at virtually every large village and keep, and knights were duty-bound to study arms for defense of church and realm. In addition, European warriors were in a constant struggle to improve military technology. Leather armor was replaced by mail (made of chain rings), which was eventually replaced by steel plate. Late medieval plate armor itself, although uncommon on most battlefields of the day, is famous for its defensive strength and ingenious design. All myths of lumbering, encumbered knights aside, what is seldom realized is plate’s flexibility and balance as well as its superb craftsmanship and artistry. In fact, the armor used by warriors in the Middle Ages was developed to such quality that when NASA needed joint designs for its space suits, they actually studied European plate armor for hints.

An armored ninth-century Franconian warrior, assuming a defensive position with sword and shield. This figure is based on a chess piece from a set by Karl des Grossen.

Medieval knights and other warriors were also well trained in unarmed combat. Yet, there is also ample literary evidence that monks of the Middle Ages were deemed so adept at wrestling that knights were loath to contest them in any way other than armed. Unarmed techniques were included throughout the German Kunst des Fechtens (art of fighting), which included an array of bladed and staff weaponry along with unarmed skills. It taught the art of wrestling and ground fighting known as Unterhalten (holding down). The typical German Fechtmeister (fight-master) was well versed in close-quarters takedowns and grappling moves that made up what they called Ringen am Schwert (wrestling at the sword), as well as at disarming techniques called Schwertnehmen (sword taking). Practical yet sophisticated grappling techniques called collectively Gioco Stretto (usually translated as “body work”) are described and illustrated in numerous Italian fighting manuals and are in many ways indistinguishable from those of certain Asian systems.

In the 1500s, Fabian von Auerswald produced a lengthy illustrated manual of self-defense that described throws, takedowns, joint locks, and numerous traditional holds of the German grappling and ground-fighting methods. In 1509, the Collecteanea, the first published work on wrestling, by the Spanish master-of-arms Pietro Monte, appeared. Monte also produced large volumes of material on the use of a wide range of weapons and on mounted fighting. He considered wrestling, however, to be the best foundation for all personal combat. His systematic curriculum of techniques and escapes was presented as a martial art, not as a sport, and he emphasized physical conditioning and fitness. Monte’s style advocated counterfighting. Rather than direct aggressive attacks, he taught to strike the openings made by the opponent’s attack, and he advised a calculating and even temperament on the part of the fighter. He also stressed the importance of being able to fall safely and to recover one’s position in combat. Clearly, Monte’s martial arts invite comparisons to the Asian arts.

The illustrated techniques of Johanne Georg Paschen, which appeared in 1659, give an insight into a sophisticated system of unarmed defense in that the work shows a variety of techniques, including boxing jabs, finger thrusts to the face, slapping deflects, low line kicks, and numerous wrist-and armlocks. Similarly, Nicolaes Petter’s fechtbuch (fighting manual) of 1674 even includes high kicks, body throws and flips, and submission holds, as well as assorted counters against knife-wielding opponents.

Similar unarmed combat systems can be found, among other contexts, in Welsh traditions and in the modern wrestling arts of Glima in Iceland, Schwingen in Switzerland, and Yagli in Turkey. Investigation into the multitude of unarmed styles and techniques from surviving European written sources is still in its infancy.

Obviously, then, the advent of the Renaissance only accelerated the experimentation and creation of Western fighting arts. Swordsmanship continued to develop into highly complex personal fighting systems. The development of compound-hilt sword guards led to extreme point control with thrusting swords, which gave great advantage to those trained in such techniques. With warfare transformed by the widespread introduction of gunpowder, the nature and practice of individual combat changed significantly. Civilian schools of fencing and fighting proliferated in these times, replacing the older orders of warriors. Civilian “Masters of Defence” in Italy, Spain, and elsewhere were sought after for instruction, and members of professional fighting guilds taught in England and the German states.

The art of sword and buckler (small hand-shield) was also a popular one throughout Western Europe at this time. It was once even practiced as a martial sport by thirteenth-century German monks. This pastime served to develop fitness as well as to provide self-defense skills. Sword and buckler practice was especially popular in northern Italy, also. Later, among commoners in Elizabethan England, it became something of a national sport. Similar to the sword and shield of the medieval battlefield, the sword and buckler was a versatile and effective combination for war as well as civilian brawling and personal duels. Its nonmilitary application eventually contributed to the development of an entirely new civilian sword form, the vicious rapier.

The slender, surprisingly vicious rapier was an urban weapon for personal self-defense rather than a military sword intended for battlefield use, and indeed, was one of the first truly civilian weapons developed in any society. It rose from a practical street-fighting tool to the instrument of a “gentleman’s” martial art in Western and Central Europe from roughly 1500 to 1700. No equivalent to this unique weapon form and its sophisticated manner of use is found in Asian societies, and no better example of a distinctly Western martial art can be seen. The rapier is a thrusting weapon with considerable range and a linear style well suited to exceedingly quick and penetrating attacks from difficult angles. Dueling and urban violence spurred the development of numerous fencing schools and rapier fighting styles. The practitioners of rapier fencing were innovative martialists at a time when European society was experiencing radical transformations. By the late 1600s, this environment led to the creation of the fencing salons and salles (“halls”) of the upper classes for instruction in dueling with the small-sword. The small-sword was an elegant tool for defending gentlemanly honor and reputation with deadly precision. An extremely fast and deceptive thrusting tool, it has distant sporting descendants in the modern Olympic foil and epee. Both rapier and smallsword fencing incorporated the use of the dagger and an array of unarmed fighting techniques. Each was far more martial than the sporting versions of today and far more precise than the amusing swashbuckling nonsense of contemporary films.

An old German woodcut illustrating various methods of the “art of fighting,” Kunst des Fechtens, which included an array of bladed and staff weaponry along with unarmed skills.

Russia was also a land where martial arts were in constant development. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, before the Mongol invasions, Russian warriors wore armor of high quality and wielded shields and long-swords in deadly combination. A Russian proverb confidently stated that a two-bladed sword from the Rodina (motherland) was more than a match for any one-bladed scimitar from the “pagans” (Muslims and Tartars). When Peter the Great assumed power in 1682, Russian peasants were so proficient at stickfighting that one of his first official acts was to put a stop to it. Peter was going to war against the Ottoman and Swedish empires, and he was going to need healthy troops for the army. In the stick-

This “art of fighting” also included the art of wrestling and ground fighting known as Unterhalten (“holding down”) and close-quarters takedowns and grappling moves, shown here in this Albrecht Duerer illustration.

This “art of fighting” also included the art of wrestling and ground fighting known as Unterhalten (“holding down”) and close-quarters takedowns and grappling moves, shown here in this Albrecht Duerer illustration. (Courtesy of John Clements) fighting matches, a favorite village pastime, both combatants often were severely injured.

Russians also have a long history of indigenous wrestling traditions. Accounts from writers in the 1700s describe wrestling matches that lasted a great portion of the day, ending only when the victor had his opponent in a joint lock. We also know that as the Russian Empire expanded into Central Asia, the officers would write of native wrestling systems. Local wrestling champions from these conquered areas sometimes would be pitted against soldiers from the invading armies. Joint locks and choke holds were commonly mentioned as ways that such fights ended.

As they began the exploration and conquest of the globe, Western Europeans carried their martial systems with them. The Spanish, for example, maintained their own venerable method of fighting, La Destreza (literally, “dexterity,” “skill,” “ability,” or “art”—more loosely used to mean “Philosophy of the Weapons” or “The Art and Science” of fighting). Spanish strategic military science and the personal skill of soldiers played a major role in the defeat of their opposing empires in the Americas and in the Philippines. It has been suggested in fact that the native fighting systems of these islands and Spanish techniques are blended in the modern Filipino martial arts.

Also during this time, new Western unarmed combat systems were being created and refined. Two examples that are still with us today are French savate and Brazilian capoeira. Since both systems developed as street combat styles rather than among the educated and literate classes, the origins of both are subjects of speculation and the oral traditions generated by such conjecture.

According to popular tradition, capoeira is a system of hand-to-hand combat developed by African slaves transplanted to work on the Portuguese plantations of Brazil. The style of fighting involves relatively little use of the hands for blocking or striking as compared to foot strikes, trips, and sweeps, and it often requires the practitioner to assume an inverted position through handstands and cartwheels. One of the most popular explanations for these unique characteristics is that with their hands chained, the African slaves took their native dances, which often involved the use of handsprings, cartwheels, and handstands, and created a system of self-defense that could be performed when manacled. Following emancipation in the nineteenth century, capoeira became associated with the urban criminal. This association kept the art in the streets and underground until well into the twentieth century. Currently, the art is practiced in what is regarded as the more traditional Angola form and the Regional form that shows the influence of other (perhaps even Asian) arts. In either form, however, capoeira is a martial art that developed in the New World.

The origins of savate are equally controversial, but it is known that by the end of the seventeenth century, French sailors fought with their feet as well as their hands. Although savate is the best known, various related foot-fighting arts existed throughout Europe. Like capoeira, savate began as a system associated with the lower and criminal classes but eventually found a following in salles similar to those European salons devoted to swordsmanship. Savate, in fact, incorporates forms using canes, bladed weapons, and wrestling techniques. A sporting form of savate—Boxe Frangaise—survives into the contemporary period, as well as a more self-defense-oriented version—Danse de rue Savate (loosely, “Dance of the Street Savate”). Modern savate (especially Boxe Frangaise) incorporates many of the hand strikes of boxing along with the foot techniques of the original art. Among the practitioners of this outstanding fighting art were Alexandre Dumas and Jules Verne. Indeed, the character of Passepartout in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days is a savate expert who is called upon to save his employer.

Despite gaps in the historical record, it is apparent that for better than two millennia unarmed combat was developed, refined, and practiced by cultures as empires rose and fell. Armed combat shifted and changed with the advent of new and improved military technology. Clearly, fighting systems that required sophisticated training and practice have been in use in the “Western” regions of the globe as long as many Asian martial arts.

The development of firearms, however, led to an unprecedented technological revolution in Western military science that radically changed ideas of warfare and personal safety in that sector of the world. By the late 1600s, the firearm was the principal tool of personal and battlefield combat, and all practical armor was useless against it. The availability of pistols discouraged the use of rapiers or small-swords for personal defense or as dueling weapons. At the time of the American Civil War, repeating revolvers and rifles, Gatling guns, and cannons loaded with grapeshot ensured that attempts to use swords and cavalry charges against soldiers armed with such weapons would end as massacres.

In the twentieth century the West “discovered,” and in many cases redefined, Asian martial arts and recovered many of their own fighting traditions. For example, the contemporary Russian martial art of sambo (an acronym in Russian for “self-defense without weapons”) draws on both European and Asian systems for its repertoire of techniques. Sambo was developed in the 1920s by Anatolij Kharlampiev, who spent years traveling around the former Soviet Union analyzing and observing the native fighting systems. He duly recorded and freely borrowed techniques from Greco-Roman and freestyle wrestling (from the Baltic States), Georgian jacket wrestling, Khokh (the traditional fighting system of Armenia), traditional Russian wrestling, Turkish wrestling systems from Azerbaijan and Central Asia, and Kodokan Judo. The result was a fighting system that was so effective that when it was first introduced by European judoka (Japanese; judo practitioners) in the early 1960s, the Soviets won every match. The Soviets also were the first to best the Japanese at their own sport of judo in the 1972 Munich Olympics. The Soviet competitors were sambo practitioners cross-trained in judo rules.

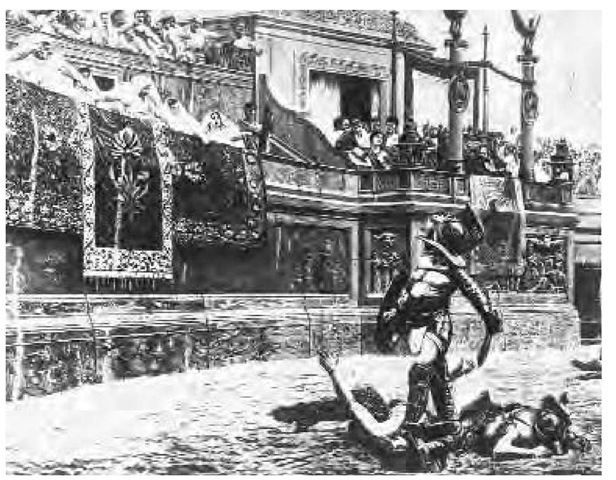

Illustration published in 1958 of a victorious gladiator standing over his defeated opponent as the crowd gives the thumbs down, indicating death, at the Colosseum in Rome.

An example of the redefinition of Asian martial arts can be found in the 1990s craze of Brazilian jiu-jitsu. Although accounts of the creation of the art vary, it is generally accepted that Helio Gracie, the founder of Gra-cie Jiu-jitsu, studied briefly with a Japanese jujutsu instructor and then began to formulate his own system. He was very successful; the Ultimate Fighting Championship, which has achieved worldwide fame, is a variation of the Vale Tudo (Portuguese; total combat) of Brazil where Gracie practitioners reign supreme. Karateka (Japanese; practitioners of karate) and other Asian martial artists have been far less successful.

A similar redefinition is found in the contemporary Israeli martial art of krav maga (Hebrew; contact combat), developed by Imi Lichtenfeld. It is the official fighting art of the Jewish State. Rather than relying on an Asian model, however, Lichtenfeld synthesized Western boxing and several styles of grappling to create a fighting art that is easy to learn and extremely effective.

These unarmed fighting arts demonstrate that Westerners are far from unlearned in hand-to-hand combat. Such traditions are part of Western history.

While it has been said that there are many universal principles common to all forms of fighting, it is misleading and simplistic to suggest that Eastern and Western systems are all fundamentally the same. There are significant technical and conceptual differences between Asian and European systems. If there were not, the military histories, the swords, and the arms and armor of each would not have been so different. Forcing too many similarities does a disservice to the qualities that make each unique.

As both military science and society in the West changed, most indigenous martial arts were relegated to the role of sports and obscure pastimes. Sport boxing, wrestling, and sport fencing are the very blunt and shallow tip of a deep history that, when explored and developed properly, provides a link to traditions that are as rich and complex as any to emerge from Asia.

Currently, however, efforts are under way to perpetuate and revive traditional martial arts of the Western world. For example, armed combat using the weapons of medieval and Renaissance Europe is being rediscovered by organizations whose members have drawn on the historical fighting texts of Masters of Defence for guidance. Today, as more and more students of historical European martial arts move away from mere sport, role-playing, and theatrics, a more realistic appreciation and representation of Western fighting skills and arms is emerging.