So wrote Herman Melville in the year 1851, thus echoing - the common lament of whalers that the fastest (and some of the largest) species of whales, such as the finback (Bal-aenoptera physalus) and the blue (B. muscuhts), lay beyond contemporary means of capture. At the time that Melville wrote Moby Dick, the basic technology of whaling had remained essentially unchanged for centuries. Whaling ships plied their trade under sail, and the small boats that they lowered to pursue whales were also powered by wind or by the brute strength of their crew’s arms at the oars. The killing of whales required men to bring their frail craft alongside the huge quarry, subduing and fastening to it with hand-thrown harpoons. If this dangerous series of actions succeeded, the whale might ultimately be despatched with a lance thrust deep into some vital organ. Once killed, the carcass would be either towed to shore or brought alongside the whaling vessel for the time-consuming process of flensing and “trying out” (boiling) the blubber for oil.

I. The Emergence of Modern Whaling

These methods had been in use in the 11th century when the Basques began the first sustained commercial whale fishery on right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) in the Bay of Biscay. Although many improvements had been made, the technology available to whalers in the middle of the 19th century severely limited the number of animals that could be taken and processed in a working day. Furthermore, as Melville noted, it largely precluded exploitation of the faster species. Blue, fin,sei (B. borealis), and Bryde’s whales (B. brydei/edeni). all large and desirable targets, were too swift to allow pursuit by oars or sails. Thus it was the slower species such as the humpback, the right, and the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) that had borne the brunt of commercial whaling, and they had done so in some cases for almost a thousand years.

By 1860, however, all of this was about to change. Two men, the Norwegian Svend F0yn and an American named Thomas Welcome Roys, were independently experimenting with explosive harpoons. As patented by Roys in 1861, this device was initially fired from a shoulder gun; F0yn developed a different approach using a bow-mounted cannon, which was to become the industry standard. The “bomb lance” was an innovation that was to revolutionize the whaling industry by providing a much more efficient means to dispatch whales, both quickly and from a distance.

About the same time, the use of sail was beginning to give way to steam. This was a key innovation; together with the explosive harpoon, it radically changed the industry and finally allowed the pursuit and capture of any whale. Suddenly, even the fastest rorquals came under the threat of the harpoon as they were chased down by fast motorized catcher boats.

A further innovation, the compressor, solved a long-standing problem with regard to the many species that did not float when dead: by pumping air into the carcass immediately after death, whalers could secure it before it sank, thus reducing the loss rate greatly.

For the industry, this transition into the mechanized age could not have come at a more opportune time. By 1900, many populations of the traditionally hunted species were commercially exhausted. For some populations, such as the bowhead (Balaena mysticetus) and the North Atlantic right whale this was the result of exploitation spread over centuries. With some other stocks, decimation had been accomplished in a remarkably short time: the first North Pacific right whale (E. japonica) was not killed until 1835, yet 14 years later the population had already been reduced to the point where many whalers switched their focus to the newly established fishery for bowhead whales in the western Arctic. Another quickly depleted stock was that of the eastern North Pacific gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus), made vulnerable by its predictable coastal migration and tendency to concentrate for breeding and calving in the lagoons of Baja California.

The new technology opened up all species to whaling and did so at a time when the industry, spurred on by steam power, was also expanding geographically. By far the most significant development in this regard was the discovery of the vast stocks of whales in the Southern Ocean. In 1904, the Norwegian whaler C. F. Larsen arrived at the South Atlantic island of South Georgia and reported with astonishment, “I see them in hundreds and thousands.” Huge pristine populations of rorquals—notably blues, fin whales, and humpbacks (Megaptera novaeangliae)— filled the surrounding waters together with southern right whales (£. australis) and other species. Modern whaling had found its last and greatest reserve. A slaughter unparalleled in whaling history was about to begin.

Whaling at South Georgia was initially constrained by the need to use land stations for processing of the carcasses. Be cause of this, the time to spoilage limited the range of the catcher boats; it also left the whaling companies vulnerable to high taxes levied by the British authorities. Despite these difficulties, the industry accomplished the destruction of local stocks of whales with remarkable efficiency. At the height of operations, hundreds of humpback, fin, and blue were taken in a single month. By 1915 the South Georgia population of humpbacks had essentially been extirpated, with a total catch of some 18,557 whales; while occasional catches were made in later years (the largest being 238 humpbacks in 1945/1946), the stock was commercially extinct by the time of the Great War. Blue whales suffered a similar fate: 39,296 were killed at South Georgia between 1904 and 1936, at which point the population had crashed, apparently irretrievably.

The problem of dependence on land stations was solved, at a stroke, with the introduction of the factory ship. The British vessel Lansing was the first such floating factory and began operations in Antarctic waters in 1925. It is difficult to overestimate the importance of this innovation to whaling or its contribution to the destruction of whale populations in the Antarctic. Factory ships could operate independently far out to sea for months at a time. They maintained round-the-clock processing operations in the long Antarctic days, their huge flensing decks kept constantly supplied by an attendant fleet of catcher boats. Whale carcasses were hauled up the large stern ramp and dismembered with astonishing mechanical efficiency: an adult fin whale of 70 or 80 feet and 100 tons could be rendered from whole animal down to bone in half an hour. With the factory ship, all of Antarctic waters became open to whalers, their operations limited only by the constant dangers of weather and ice.

Over the six decades following the opening of the Antarctic grounds in 1904, the whaling industry killed approximately 2 million whales in the Southern Hemisphere (Table I). This included 360,000 blue whales, some 200,000 humpbacks, more than 400,000 sperm whales, and a staggering 725,000 fin whales (Table 1). By the 1930s, it was apparent even to the whaling nations that some kind of regulation was required. In 1931, the Convention for the Regulation of Whaling was held and adopted worldwide protection for right whales, an action that came into effect in 1935, The second Convention for the Regulation of Whaling was held in 1937 and provided protection for the much-depleted gray whale. However, neither convention went far enough; among other things, because neither Japan nor the Soviet Union ratified these agreements, both were theoretically free to continue killing the only two species that had been granted protection.

II. Advent of the International Whaling Commission

In 1946, following the virtual cessation of whaling that occurred during World War II, the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling was developed and signed by all major whaling nations (including Japan and the USSR). Among other things, this landmark convention created the International Whaling Commission (IWC), established to regulate whaling and to oversee research on whale stocks. The latter task had as its principal objective management that would allow the highest viable level of exploitation, a concept widely known as maximum sustainable yield (MSY). This required collection and analysis of information on abundance, population structure, and life history of the great whales to permit setting of quotas.

TABLE I

Southern Hemisphere Catch Totals (1904-2000)”

|

Blue |

360,644 |

|

Fin |

725,116 |

|

Sei |

203,538 |

|

Humpback |

208,359 |

|

Bryde’s |

7,757 |

|

Minke |

116.568 |

|

Right |

4,338 |

|

Sperm |

401.670 |

|

Other |

11,631 |

|

Total |

2,039,621 |

“Primary sources IWC, 1995; Yablokov et al, 1998.

Unfortunately, the quota system of die IWC was immediately handicapped by an earlier development. In 1932, the whaling nations had developed the “blue whale unit” (bwu). A single bwu was equivalent to one blue whale, two fin whales, two and a half humpbacks, or six sei whales. As such, quotas set in bwu, by permitting whalers to make their own decisions about which whales to take, made no allowance for the conservation status of a particular species, let alone that of a specific population. It was not until 1949 that a species-specific quota (for humpbacks) was established.

The bwu remained in effect until 1972, despite recommendations from IWC scientists as early as 1963 that it be abolished (also in 1963, the same scientists recommended a halt to all humpback and blue whaling; the IWC responded by setting a quota of 10,000 bwu). In some years, the IWC could not agree on a bwu quota, and whaling nations were left to make their own informal agreements on catch levels. Overall, the bwu arguably represents the most ill-conceived and damaging management strategy in IWC history. However, it was far from the only problem in the commission’s management of whale populations.

From its inception, the IWC was hampered by the unwillingness of the whaling nations to acknowledge the mounting evidence of decline in whale populations and by the complete lack of any enforcement or independent inspection measures. That the first humpback whale quota in 1949 was immediately exceeded in the three subsequent Antarctic seasons pointedly highlighted the latter issue. Additional examples followed, but it was not until the 1990s that the true extent of this problem became apparent, and it was more egregious than anyone could have predicted.

In 1993, following the end of the Cold War, former Soviet biologists revealed that the USSR had conducted a massive campaign of illegal whaling beginning shortly after World War II. Soviet factory fleets had killed virtually all whales they encountered, irrespective of size, age, or protected status. The scale of this deception was staggering: in all, the difference between the reported take of the USSR and its actual catches was more than 100,000 animals in the Southern Hemisphere alone (Table II). Of these, the humpback whale was the most heavily impacted: reporting 2710 catches to the IWC, the Soviets had in fact taken more than 48,000. In the Northern Hemisphere, Soviet activities were on a smaller scale, but were nonetheless extremely damaging in some cases. The virtual disappearance of right whales in the eastern North Pacific in the 1960s was re-cendy explained by revelations of Soviet catches of 372 whales from this already depleted stock between 1963 and 1967.

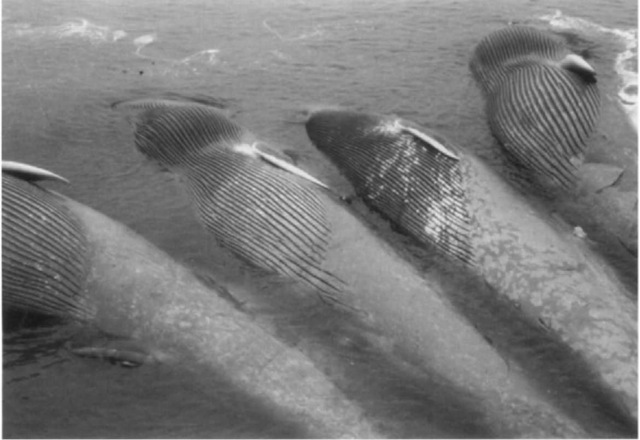

Figure 1 These blue whales are among those harvested worldwide during the 20th century. Over 360,000 animals were harvested from the Southern Hemisphere alone.

In retrospect, it is possible to see clues to this unfolding catastrophe. Beginning in 1959, at a time when there was increasing discussion of declining populations and the need for diminished quotas, the Soviets began adding a new factory ship each year to their Antarctic fleet. This included the Sovetskaya Ukraina, the largest floating factory ever built, with an attendant fleet of 25 catcher vessels. In a single season (1959/1960), Sovetskaija Ukraina and a second factory, the Slava, killed almost 13,000 humpbacks, mainly from the high-latitude waters south of Australia, New Zealand, and western Oceania. In addition, the intransigence of die USSR in its opposition to a pro posed international observer scheme (IOS, to permit independent inspections of catches at sea) is now easy to interpret. The illegal catches continued until adoption and implementation of the IOS was finally accomplished in the early 1970s.

In the latter part of the 1960s the IWC finally began to respond to the increasing evidence that whale populations had been exploited well beyond MSY. Blue whales were protected in 1965, and quotas for fin and sei whales were reduced in the late 1960s in response to declines in catches. Nonetheless, any enforcement remained absent, and the Soviets secretly continued to kill whales irrespective of quota or protection.

III. The Decline of Commercial Whaling

In the following decade, however, a sea change occurred at the IWC. The composition of the commission slowly shifted as nonwhaling nations joined, while others ceased whaling and developed instead into advocates for conservation. A whaling moratorium was proposed by the United States and Mexico as early as 1974, but this and later proposals were rejected by IWC until 1982. In that year, a radically changed commission finally achieved the necessary votes to pass a 10-year moratorium. Predictably, Japan, Norway, and the Soviet Union objected. The moratorium went into effect in 1986, with a zero catch quota for both pelagic and coastal whaling.

TABLE 11

Reported versus Actual Catches by the USSR”

|

Reported |

Actual |

|

|

Blue |

3.651 |

3,642 |

|

Pv’gmv blue |

10 |

8,439 |

|

Fin |

52,931 |

41,184 |

|

Sei |

33,001 |

50,034 |

|

Humpback |

2,710 |

48,477 |

|

Biyde’s |

19 |

1,418 |

|

Minke |

17,079 |

14,002 |

|

Right |

4 |

3,212 |

|

Sperm |

74,834 |

89,493 |

|

Other |

1,539 |

1,745 |

|

Total |

185,778 |

261.646 |

“Note that some catches were actnallv overreported; this was to disguise takes of protected species by overreporting catches of species that were legally huntable at the time.

At this point in time Soviet whaling was coming to an end; with aging capital and the imminent dissolution of the USSR, the nation that had wreaked so much havoc on whale populations (a fact still unknown at this time) slowly removed itself from the business of commercial whaling. Japan. Norway, and Iceland, however, remained active, and in 1987 they effectively circumvented the moratorium by beginning “scientific” whaling. This act exploited a provision in the convention that allows member nations to issue themselves permits to conduct whaling for scientific research; it was originally included at a time when the onlv way in which any information could be gathered about whales was to kill them. As opponents of scientific whaling pointed out, the emergence in the 1970s of long-term studies of living whales (frequently based on the identification of individual animals) provided a much better means to study the biology and behavior of cetaceans.

The stated reason for the moratorium was to permit world whale stocks to recover from the overexploitation to which they had been subject. In the meantime, the IWC’s scientific committee was charged with developing a new management procedure for future management of stocks and setting of quotas. After considerable debate, the so-called revised management procedure (RMP) was accepted by the scientific committee in 1994. The RMP is a computer model for determining the level of allowable commercial catches for a stock based on its current abundance, histoiy of exploitation, levels of incidental takes, and overlap with adjacent stocks having differing catch histories. However, the scheme by which the RMP would actually be implemented had still not been adopted in 2001, and there remains considerable resistance to the idea of the IWC endorsing a program that would effectively permit the resumption of commercial whaling. In 1994, Norway preempted such an agreement by resuming commercial whaling under “objection” to the moratorium and used the RMP to set its own catch quotas for minke whales in the northeastern North Atlantic.

The reluctance of many nations to implement the RMP stems largely from lingering concerns regarding enforcement and transparency in whaling operations. The whaling nations maintain that adequate measures are now in place to ensure compliance with quotas set under the RMP. Opponents disagree, pointing to the history of deception in modem whaling and noting more recent evidence that such deception continues to exist. In particular, considerable attention has been focused on the use of forensic genetics to test samples of whale meat in Japanese markets; although the only meat that should be found there is that from minke whales (B. acutorostrata and B. bonaerensis) taken in Japanese scientific catches, numerous other species have been detected. Although some of these animals probably represent bycatch (incidental entrapment in fishing gear), their presence reinforces the fact that there is currently no means to adequately track whale products at every stage from catch to market. A DNA register of all animals taken in Japanese and Norwegian hunts has been proposed, but it has yet to be fully developed and accepted by the IWC; the resolution of this issue is not aided by the whaling nations insistence that any discussion of trade in whale products lies widiin the purview not of the IWC but rather of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) or the World Trade Organization.

IV. Impacts of Whaling on the Stocks of Whales

The impact of modem whaling on the world’s stocks of whales has been varied. Many species appear to be recovering despite past exploitation, which in many cases may have reduced numbers by 90% or more from pristine levels. Humpback whales, which were extensively overhunted worldwide and which bore the brunt of illegal Soviet catches in the Southern Hemisphere, are showing strong rates of population growth in die North Atlantic, North Pacific, and some areas of the Southern Ocean. Eastern gray whales number approximately 26,000 animals and have been removed from the U.S. list of endangered species. Although no reliable estimates of abundance exist, populations of fin and sei whales are assumed to be healthy in the Northern Hemisphere; the status of the extensively exploited Antarctic populations is less clear. Similarly, sperm whales are likely to be generally abundant, although in some areas, apparently slow rates of population growth may be attributable to overexploitation of mature males in high latitudes, resulting in insufficient availability of mates that are “acceptable to adult females. Although there is considerable controversy over Japanese and Norwegian whaling, there is general agreement that some of the targeted stocks of minke whales are abundant. However, some adjacent stocks are considered depleted and could be impacted in areas where the whales mix during migration.

In contrast, other populations of whales appear to be struggling to recover from the indiscriminate exploitation to which they were subject. In some extreme cases, local populations appear to have been extirpated, with no recoveiy evident in the intervening years. Humpback and blue whales at South Georgia were commercially extinct by 1915 and 1936, respectively, and are rarely observed there today. Blue whales were wiped out from the coastal waters of Japan by about 1948, and no members of this species have been recorded there in recent years despite an often extensive survey effort. Off Gibraltar, a population of fin whales was extirpated with remarkable speed between 1921 and 1927. The population of humpbacks that used the coastal waters of New Zealand as a migratory route crashed in 1960 as a result of shore whaling and the 1959/1960 Soviet catches of almost 13,000 humpbacks in the feeding grounds to the south. A few sightings have been reported off New Zealand in recent years, perhaps suggesting that a slow recovery is underway. In the North Atlantic, right whales were removed from much of their former range largely by historical whaling prior to 1880 (the Labrador stock seems to have been wiped out by Basque whaling as early as 1610), but even here, a remnant population in European waters was extirpated by Norwegians using modern techniques at the beginning of the 20th century. The demise of at least one stock of whales can be attributed exclusively to premodern whaling: the bowhead was commercially extinct from Spitsbergen waters by 1900, and the species is rarely observed diere today.

In all of these cases, whaling essentially extirpated a stock of whales. The lack of recovery over a time scale ranging from four decades in the case of New Zealand humpbacks to almost four centuries for right whales off Labrador has important implications for the modern management of whale populations. Although it is quite likely that the observed lack of recovery was at least partly due to a simultaneous overexploitation of adjacent populations (i.e., those that might otherwise have provided a source for repopulation), these localized extirpations reinforce the belief that management units should be designed carefully on often smaller spatial scales than has been the case in the past.

Of those populations that survived, several are critically endangered. Right whales persist in low numbers in the western North Atlantic and the western North Pacific; the present size of the eastern North Pacific population is unknown, but is clearly precariously small following the immense damage done by the Soviets in the 1960s. In sharp contrast to the eastern (“California”) gray whale, the outlook for the western North Pacific population of this species is bleak. Whaling on this small stock continued in Korean waters into the 1960s, and a gray whale was found harpooned in Japan as recently as 1996. Only a hundred or so animals may remain extant today. Furthermore, nothing is known of the location of the breeding grounds for this population; if it is reliant on coastal lagoons for calving (as is a major segment of the eastern stock), the impact of coastal development and other human activities may be severe. Among bowhead populations, that in the Bering/Beaufort/ Chukchi Seas is recovering strongly despite continued exploitation by a well-managed Inuit hunt. In the eastern Arctic, a few hundred bowheads remain in Canadian waters (principally Hudson Bay/Foxe Basin and Baffin Bay/Davis Strait), while as noted earlier the Spitsbergen stock appears to be functionally extinct. Finally, blue whales have fared poorly almost everywhere; the only population that appears to be large and healthy is that which feeds off California in summer. Other blue whales, including all of those in the Southern Ocean, remain rare and highly endangered.

It is not clear what the future holds for whaling. Ultimately, it depends on the outcome of developing geopolitics: put simply, on whether the emerging worldview of commercial whaling as an anachronism prevails or, if it does not, on whether whaling can learn the lessons of its grim past. For now, the outcome remains hung in the balance.