The walrus is the single species of the pinniped family Odohenidae, distinguished by the upper canines in both sexes being prolonged as tusks. Walruses feed mainly on small organisms on the ocean floor, while almost all other pinnipeds feed primarily on highly mobile fish and crustaceans. For an animal of such a large size, this predator consumes organisms that are relatively low in the food chain. The diet of the walrus influences its biology, compared to other pinnipeds, the walrus has a less streamlined body, swims more slowly, and dives less deeply. Its sensor)’ systems are adapted to its bentic foraging technique.

I. Classification

The Latin name Odobenus rosmarus means “tooth walking sea horse.” The genus Odobenus consists of only one species: O. rosmarus. Two subspecies are recognized based on morphological characteristics and on mitochondrial DNA divergence: Pacific walrus. Odobenus rosmarus divergens (Illiger, 1815) and Atlantic walrus, O. rosmarus rosmarus (Linnaeus, 1758). A potential third subspecies, the Laptev walrus, O. rosmarus laptevi (Chap-ski, 1940), is dubiously distinct from O. rosmarus divergens.

II. External Characteristics

The walrus is the largest pinniped except for the male elephant seal (Mirounga spp). The body is rotund; the girth at axilla is almost equal to body length. Males are larger than females of the same age. Adult Pacific walruses are on average slightly larger than adult Atlantic walruses of the same gender. Adult male walruses have an average body length of around 320 cm and weight 1200-1500 kg, whereas adult females have a body length of around 270 cm and weigh 600-850 kg. Regional differences in body size per gender and age class exist.

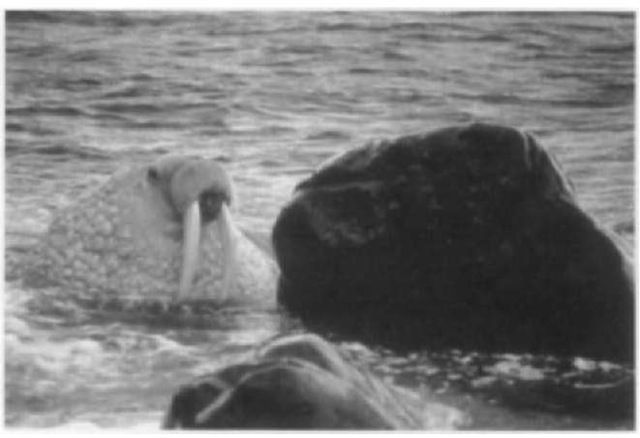

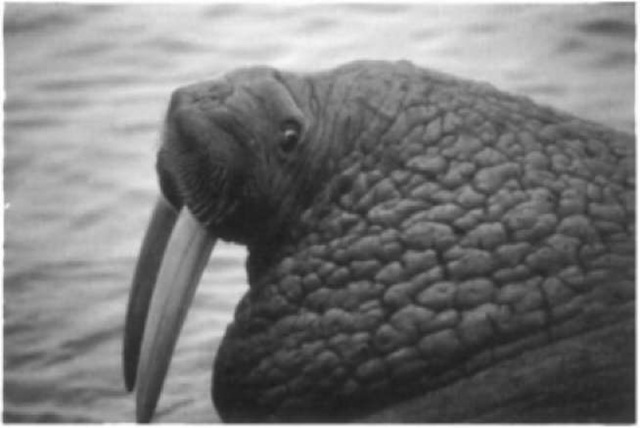

Walruses are easily distinguished from other pinnipeds by their flat noses and enlarged upper canines that form huge tusks. Males have longer and thicker tusks than females. The tusks grow throughout life but growth is usually balanced by tooth wear. The larger whiskers on the upper lips are translucent and yellowish and are directed forward. The eyes are small relative to body size compared to other pinniped species. They are positioned high on the head and can be protruded and retracted. There are no external pinnae. The color of the skin varies from a (lighter) gray when the walrus has just left cold water (Fig. 1) to a (darker) yellowish brown when it is warm and dry (Fig. 2). The fur is very short and in some areas of the body is absent. Although much variation exists, walruses generally molt inconspicuously between May and June and grow new pelage in July and August. The appendages are hairless and the palms and soles are rough. The skin is 2-4 cm thick and very tough. It is thickest around the neck (about 4 cm) and in the area above the whiskers, which is used for plowing through the ocean floor. The skin on the neck of adult males is thicker than that of females and is covered with fibrous tubercles (Fig. 2).

Figure 1 An adult male Pacific walrus just arriving nearshore from a long foraging journey at sea. Note the light gray color of the skin, which is due to a reduced blood flow to the skin during low temperatures.

Figure 2 An adult male Pacific walrus. Note the large diameter of its tusks, the bulging eye, which is turned to look backward, and the pronounced tubercles of the skin on the neck. The latter feature is only seen in adult males.

These tubercles are 1 cm thicker than the surrounding skin, protect the underlying tissues against tusk attacks by other males, and are an important visual sexual characteristic. The blubber layer thickness varies depending on the part of the body and season and can be up to 10 cm.

III. Anatomy

A. Skeleton

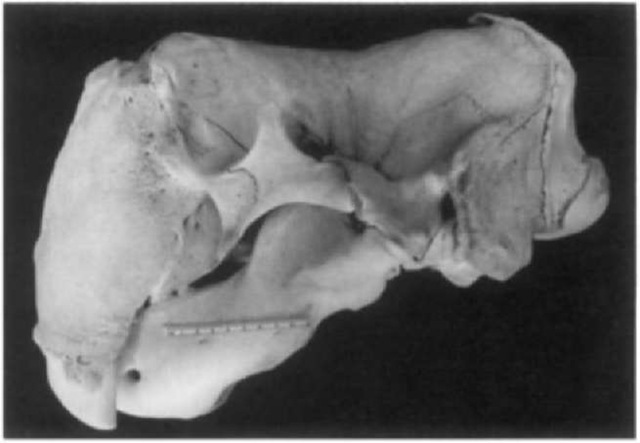

The skull has some distinct features that relate to the ecology of the walrus. It is very thick and strong as an adaptation to breaking through ice to make breathing holes. The front of the skull of an adult walrus is much higher and broader than that of other pinnipeds to accommodate the large tusks (Figs. 3 and 4). Males, which have thicker tusks than females, also have broader skulls. The tusks are composed of dentine covered with a thin layer of cementum. The ivory of walruses can be distinguished from that of other mammals by its central globular dentine. The heavy weight of the lower jaw probably serves to increase the impact of the tusks. The walrus is able to use its tusks to haul its body upward onto land or ice because of the strong neck muscles attached to the large mastoid processes and the strong hinge between these processes: the condyle of the occipital bone. The zygomatic arch below the orbital cavity contains a strip of cartilage, probably to dampen shocks from the tusks to the braincase. In contrast to most pinnipeds, the orbital cavity is not closed on the dorsal side of the head, allowing the walrus to look upward during plowing through the substrate.

Figure 3 A ventral view of a Pacific walrus skull showing the large mastoid processes on the sides and well-developed occipital condyle (the hinge to the neck vertebra), the arched roof of the mouth, and the heavy lower jaw.

Figure 4 A side view of a Pacific walrus skull showing the open dorsal side of the orbital cavity and the slit in the zygomatic arch, which in life is filled with cartilage.

The spinal column consists of 7 cervical, 14 thoracic (occasionally 15), 6 lumbar (occasionally 5), 4 sacral, and 8 or 9 caudal vertebrae. There are 14-15 pairs of ribs.

The hind flippers of the walrus rotate forward like those of otariids, for locomotion on ice and land. The females have a 1- to 2-cm-long clitoris bone. The penis bone (baculum) of adult males is up to 62 cm long.

B. Muscles

Many of the muscles in the upper hp of the walrus are used to erect the whiskers in unison, although whiskers can be moved individually, as well.

The tongue muscles are very strong and are used to create a low pressure in the mouth to extract the soft parts from clams. The mastication muscles are not very large, as the walrus usually does not chew its prey but swallows it whole. The cheek muscles are strong so that the walrus can produce powerful water jets from its mouth to wash sediment away from its prey.

The muscles in the hind limbs are similar to those in otariids. The adult walrus is so heavy and rotund that it does not lift its belly off the substrate when it moves on land or ice. Only calves can walk with only their flippers touching the substrate. In the water the hind flippers are used for propulsion and the front flippers mainly for steering.

C. Respiratory System

The trachea is supported by cartilaginous rings throughout its length. It passes between the lungs for a third of their length before bifurcating into bronchi. The lateral walls of the pharynx of subadult and adult males are extremely elastic and, when inflated, form air sacs (pharyncheal pouches). These sacs are used as resonance chambers for the production of the bell-like sounds underwater and also for floatation when resting in the water.

D. Digestive System

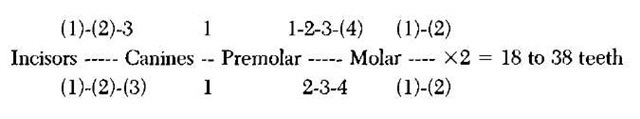

The mouth is narrow and bordered by the tusks. The roof of the mouth is very concave, allowing room for the large tongue that acts as a piston when retracted quickly. The force (of up to —119 kPa) generated by this piston is used to extract the soft parts of clams from their shells. Nontusk teeth are worn down to the gums in wild animals, perhaps by sand moving in the mouth during feeding. Teeth are pointed in captive walruses that are fed fish. The dental formula of the Pacific walrus’ permanent dentition is as follows:

Teeth in parentheses are present in less than 50% of the adult specimens.

The tip of the tongue may be rounded or bifid. The stomach consists of one J-shaped cavity. The intestines are 10-15 times the length of die animal.

E. Cardiovascular System

A conspicuous aortic bulb is present at the base of the aortic arch. The arteries to the fore limbs are larger than those to the hind limbs. This is related to the division of the muscle masses for the limbs; the muscles of the neck and shoulders are more developed than those of the pelvis area.

E Reproductive System

The testes are situated between the skin and the muscles. The penis is normally retracted into an opening posterior to the umbilicus. The uterus is bicornate and each horn opens separately into the vagina. Walruses usually have four nipples.

IV. Habitat

The walrus is found in the Arctic, where its distribution is limited by the availability of shallow water foraging grounds and thickness of ice. Walruses prefer relatively shallow water over continental shelves because they feed on invertebrates, which occur on the ocean floor up to a depth of about 80 m. Walruses can break through ice up to about 20 cm thick, but when the ice is thicker than this, they retreat to areas with drift ice. Thus, in winter, walruses inhabit diose regions of the drifting ice where leads and polynyas (open water) are numerous and where the ice is thick enough to support their weight.

Male Pacific walruses rest in traditional terrestrial haul-out sites (sand, cobble, or boulder beaches), whereas females and calves prefer to haul out on pack ice or ice floes. In summer, males rest and molt while hauled out on land close to their feeding grounds (Fig. 5). Females molt when hauled out on ice. Atlantic walruses also molt in the summer; during that time, both males and females (sometimes in the same groups) haul out on both land and ice.

V. Distribution, Migration, Abundance, and Conservation Status

The Pacific walrus is found principally in the Bering Sea south to Bristol Bay and Kamchatka and in the Chukchi Sea, although in summer it may enter the Beaufort Sea and East Siberian Sea (Fig. 6). Breeding occurs in late winter in the marginal ice zone of the Bering Sea. The location of the main breeding sites varies depending on the state of the ice, but is generally southwest of Nunivak Island and southwest of St. Lawrence Island. Pacific walruses move north in spring with the receding and drifting ice; females give birth on ice floes, which drift north. They move south in autumn, following the movement of the pack ice. Their swimming speed is approximately 10 km/hr. For most of the year, sexes and age classes live separately. The population is estimated at around 200,000 animals.

The Atlantic walrus is found in the western and eastern Atlantic Arctic (Fig. 6). Within dieir range, Atlantic walruses occur in several (perhaps eight) more or less well-defined subpopulations: five to the west and three to die east of Greenland. In the western Atlantic Arctic, walruses range from die East Canadian Arctic to West Greenland, including Davis Strait, Baffin Bay, the archipelago in the Canadian high Arctic, and Foxe Basin. The western Atlantic population is estimated at > 10,000. In the eastern Atlantic Arctic, walruses range from eastern Greenland to Svalbard (Norway), Franz Josef Land (Russia), and the Barents and Kara Seas. The eastern Atlantic population is estimated to be in the low thousands. Movement studies have shown a connection between walruses at Franz Josef Land and Svalbard and between the latter area and eastern Greenland.

The Laptev walrus (if this population is recognized as a subspecies) is found only in the Laptev Sea (Fig. 6). The population has been estimated at 4000-5000 animals.

Figure 5 A large group of male Pacific walmses hauled out on Round Island, Bristol Bay, Alaska. Note how closely the animals are packed together.

Figure 6 Distribution of the three walrus subspecies (the recognition of the Laptev walrus as a subspecies is controversial).

Atlantic walrus stocks were reduced greatly by intense exploitation in the 18th and 19th centuries by European whalers and sealers (for ivory, oil, and hides) and appears not to have recovered fully. The Pacific walrus population recovered from intense hunting, but, for unknown reasons, may have started to decline again.

Atlantic walruses are still hunted for subsistence by native people of Canada and Greenland. Pacific walruses are taken by indigenous peoples of Russia and the United States (Alaska) for the same purpose. Atlantic walruses are fully protected at Sval-bard (since 1952) and in the western Russian Arctic (since 1956). Potential threats to walrus populations are overhunting, competition with shellfish fisheries, accidental bycatch by trawlers, pollution (PCBs, heavy metals, nuclear radiation), waterborne noise at their foraging areas, aerial acoustic disturbances at their resting places (snowmobiles, aircraft, ships, oil, and gas exploration), and habitat destruction from bottom trawling.

VI. Behavior and Reproduction

Male and female walruses usually do not have contact with each other for most of the year, but animals of each sex congregate in large numbers in both winter and summer. Walruses seem to prefer being in groups. Walruses literally pile on top of each other (probably to conserve heat) in dense aggregations, and spend most of their haul-out time resting (Fig. 5). On land, they are usually in deep sleep and are difficult to wake up. They often he upside down, perhaps to reduce the pressure on their lungs. In this position their tusks point upward, they can stretch their necks, and surplus ear wax can drain from their ears. Body size and tusk length play important roles in establishing the hierarchy at haul-out sites. The tusks are used for display and as weapons in fights between walruses and against polar bears (Ursus maritimus) and killer whales (Orcinus orca) (which may prey on walrus calves). They also aid in hauling out on ice floes and shores and serve to enlarge and keep open breathing holes in the ice. In addition they function to hold heads above water by resting on the edges of ice floes.

Several aerial acoustic signals are used in social context: barking, coughing, and roaring when excited, whistling by males during the reproductive period (source levels of around 120 dB re 1 pW have been recorded), and soft calls from the females toward their calves. Alarm calls and other calls of calves have been described. Underwater, bell-like sounds are produced by the air sacs of adult males.

Walruses have well-developed facial muscles and can make many facial expressions, which play a role in short-range communication.

Females generally begin to ovulate at around 7 years of age (but some ovulate already at the age of 5 years) and usually give birth for the first time at the age of 9 years. Males become sexually mature at between 7 and 10 years of age, but become physically and socially mature, and therefore able to mate, at 15 years. Walruses can reach an age of 30 to 40 years.

Adult male and female walruses congregate during the mating season (January-April). Walruses are polygynous. In the mating season, adult males fight intensively in the water, evidently in competition for display sites near females. During courtship, the male walrus emits a stereotyped sequence of underwater sounds consisting of taps, knocks, pulses, and bell-like sounds. This acoustic display probably serves as an advertisement to females and as a warning to other males. Females choose a mate from among the displaying males. Copulation usually occurs in the water, but has been observed to occur on land in captivity, although a pool was available.

After a gestation period of about 15 months (including a period of delayed implantation of 4-5 months), a single calf of around 60 kg and 120 cm in length is born in spring (April-early June). Calves can swim immediately and may sometimes be carried on their mothers’ backs for a while. The coat of the calves is slate gray. They are suckled for at least a year (on land, on ice, and in the water) and are usually weaned gradually during their second year, when they begin to forage for invertebrates. Reproductive females can produce about one calf in 3 years. The calves remain near their mothers, in groups of adult females, for several years. Most calves are weaned by the age of 3 years, when males tend to join male herds. The high degree of maternal care and low predation rate result in low natural mortality in walrus calves. This probably allows the walrus to have fewer offspring then other pinnipeds, most of which produce a pup every year.

VII. Foraging Behavior

The diet of walruses consists mainly of benthic invertebrates. By far the most commonly eaten are bivalve mollusks, which are found buried in the sediment in high-density beds. How walruses find these beds is unknown. When they find a mollusk bed, they plough through the sediment with their snouts while swimming with their bodies at a 45° angle to the ocean floor to find prey items (Fig. 7). When foraging by plowing through the sea bed with its snout in search of invertebrates, the walrus uses its tusks and fore flippers as sleds while swimming with its hind flippers. Long furrows in the sediment have been observed in walrus feeding areas.

Once the walrus encounters a potential food item, it is identified quickly by the sensitive whiskers. If it is a bivalve mollusk, the foot or siphon is taken between the mobile lips, and by means of retraction of the large tongue, the soft parts are sucked from the shells and swallowed (Fig. 7). The empty shells are discarded and can be found on the ocean floor near the furrows. The walrus can produce strong water jets with its mouth to excavate its prey but can also remove sediment by producing strong water currents with movements of its fore flippers. The whiskers can be moved individually and are probably used as a tool to manipulate clams so that the foot or siphon is directed toward the walrus’ mouth. Once a prey item is in front of the mouth, the tongue probably takes over as a touch and manipulation organ.

Compared to most other pinnipeds, walruses consume organisms that are small and low in the food chain. The large walrus has to consume many small organisms and must have a very efficient feeding method. In fact, walruses dive for up to 24 min (average around 5 min). usually spend 80% of that time on the bottom, and generally obtain 40-60 clams per dive. Dive times probably vary depending on water depth, prey type, and prey density. Adult walruses require on average about 25 kg of soft clam parts per day, and a walrus has been found with 6000 prey items in its stomach. In captivity, Pacific walruses sometimes eat up to 50 kg of fish per day. Walruses probably store extra fat during summer when they can exploit their inshore foraging grounds and use this during migration when they swim in waters that are too deep to contain their prey.

Figure 7 Walruses foraging. They plow through the sediment on the ocean floor with their noses. When an object is encountered, it is identified with the whiskers. If it is a clam, the foot of the clam is taken between the lips, and the soft parts are sucked from the shell and swallowed.

Uncommonly, individual walruses may take a vertebrate diet. These animals usually kill seals and cetaceans as well as scavenge on their carcasses, from which they suck the blubber and internal organs. Seal-eating walruses thus consume organisms that are higher in the food chain than those consumed by mollusk-eating walmses and therefore carry a relatively high concentration of heavy metals and PCBs. Walruses sometimes also capture and eat seabirds.

VIII. Sensory Systems

A. Vision

The walrus has well-developed extrinsic eye muscles. The orbital cavity is not closed on the dorsal side (Fig. 4). This allows the walrus binocular vision in the frontal and dorsal direction. as it can protrude its eyes, and does so mostly when excited (Fig. 2). The lack of a roof of the orbital cavity suggests that the eyes are vulnerable to mechanical injury. However, the walrus eye has strong retractor muscles. The eyes can be pulled deep into the orbital cavity for protection, and the eye opening can be closed with thick eyelids.

Blood vessels and surrounding fat probably serve to keep the eyes warm and functional under cold conditions. Under high light conditions, the pupil is a vertical slit; during moderate light levels, key-hole shaped; and under low light conditions, circular. Retinal anatomy suggests that the walrus has color vision, but because no psychophysical tests have been carried out, it is unclear which part of the spectrum it can detect. Visual acuity appears to be less than in other pinnipeds investigated so far, and the eyes of the walrus seem to be specialized for short-range vision.

B. Touch

Because walruses dive up to 130 m and also at night, they often cannot always use vision to detect and process their prey. Instead, they use their sensitive mystacial vibrissae (whiskers). Each walrus has about 450 whiskers, which are highly innervated by sensory and motor nerves. The main sensoiy nerve (trigeminal nerve) is well developed, and the infraorbital foramen in the skull is proportionally large to accommodate it (Fig. 4). In contrast to most other pinnipeds, which probably use their whiskers to detect vibrations in the water, walruses use their whiskers to examine and manipulate small objects. In a psychophysical test, a captive walrus could distinguish a circle and a triangle that each had a surface area of 0.4 cm”*. The longer and thicker lateral whiskers are used mainly for the detection of objects, whereas the shorter and thinner ones near the mouth opening are used primarily for identification. The tip of the tongue also contains many mechanoreceptors and can be used to identify or reposition prey.

C. Olfaction

The behavior of the walrus on land and on ice suggests that it probably relies to a high degree on its sense of smell to obtain information about its surroundings. Anatomical evidence also suggests the importance of olfaction to walruses. They have large nares that can be closed during dives, and the nasal passage is highly vascularized so that air that passes through it can be heated. However, no conclusive psychophysical tests have been conducted on the olfactory sensitivity of the walrus.

D. Taste

Compared to many terrestrial mammals, the walrus has relatively few but large taste buds. However, not much is known about the taste abilities and discrimination in walruses. Anecdotal information on captive animals suggests that they are not very sensitive to (bitter) flavors that are disgusting to most terrestrial mammals.

E. Healing

The walrus has limited ability to locate the source of airborne sounds, as evidenced by its lack of pinnae (Fig. 2). When the walrus is in air, sound reaches the tympanic membrane via a large cartilaginous outer ear tube. The aerial hearing has been tested and is less acute than that of humans in the frequency range tested (125 Hz-8 kHz).

When diving, the walrus closes its auditory meatus and hears by tissue conduction, probably mainly via the vascular lining of the outer ear tube. The underwater hearing range of the walrus has an upper frequency limit of 16 kHz.

IX. Captivity

The first walruses in captivity were in Denmark and Germany. Later, zoological parks in the Netherlands, United States, and Russia began keeping this species.

Captive walruses often ingest foreign objects that they cannot digest. A walrus can even die from consuming too many dead leaves that sometimes drop in pools in autumn. Another problem is the wearing down of tusks on the pool floor and walls, which, in severe cases, can cause root infections.

When cared for properly, walruses are friendly and easily trained. They can perform for the public as well as in psychophysical research projects. Occasionally, males become difficult to handle after they reach maturity. Walmses can be kept in good health on a diet of whole fish, which they swallow without chewing. Reproduction in parks and zoos has improved in the last decade, but only a few calves have been raised by their mothers, as walrus mothers are very protective of their calves toward both conspecifics and humans. This causes the mother to neglect her calf (she spends more time defending the calf than nursing it) or reduces the production of milk. The main problem in the early years of husbandly was the lack of a good formula to raise calves that had been captured from the wild. This problem has been overcome, and calves from the wild or captive-born now can be hand-raised without nutritional deficiencies.