The tucuxi is listed as insufficiently known by the World Conservation Union (IUCN). Most information on the species comes from specimens collected throughout the Amazon Basin; the scarcity of data on the coastal tucuxi is a result of the lack of long-term longitudinal studies of living animals. The scenario has changed since the early and mid 1990 s, mostly through research conducted off Brazil. However, few of these studies’ results have been published and so far only presented to scientific conferences and conservation meetings and in academic theses. This article intends to include all available information to provide the best overview of the species.

I. Common Names, Distribution, and General Description

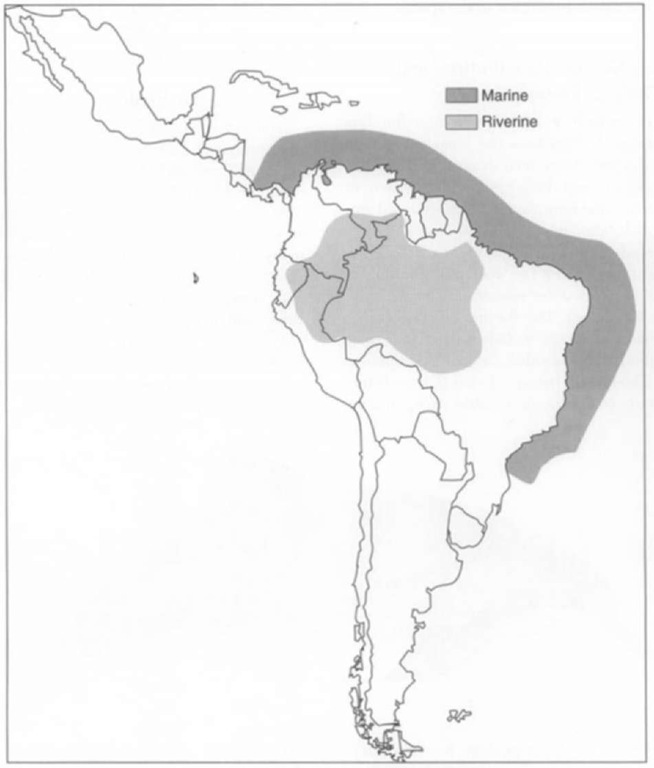

The name tucuxi comes from tucuchi-una after the Tupi language of the Mayanas Indians from the Amazon region in Brazil. Other names include boto, boto comum, and golfinho cinza along the Brazilian coast; bufeo gris, bufeo bianco, or bufeo negro in Colombia and Peru; lam in Nicaragua; and gray river dolphin in English. Although up to five species and three subspecies were described, today a single species, Sotaliaflu-viatilis, is recognized, presenting two ecotypes, riverine (or freshwater) and marine, which differ somewhat in length, number of teeth, and color pattern. The riverine tucuxi occurs in the Amazon River basin (drainage) including Brazil and going as far inland as southeastern Colombia, eastern Ecuador, and northeastern Peru. The marine tucuxi is found in the western Atlantic coastal waters of South and Central America from southern Brazil (27°35′S, 48°35′W) to Nicaragua (14°35′N, 83°14′W), including Colombia, Costa Rica, French Guyana, Guyana, Panama, Suriname, Trinidad, and Venezuela, with possible records to Honduras (15°58′N, 79°54′W). In the Orinoco River the species may be seen as far up as Ciudad Bolivar, although whether these specimens belong to the riverine or marine ecotype is not clear. No fossil record is known so far.

The tucuxi looks somewhat like a smaller bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops truncatus. It is light gray to bluish gray on the back and pinkish to light gray on the ventral region, with a distinct boundary from the mouth gape to the flipper’s leading edge. On the sides the tucuxi has a lighter area between the flippers and the dorsal fin and another one in the midbody at the anus level; marine individuals may have another light gray rounded streak on both sides of the caudal peduncle. The eyes are large, and around the eyelids there are black countershad-ings. The dorsal fin is triangular and sometimes slightly hooked at the tip (Fig. 1). It has a moderately slender long beak, a rounded melon, and 26 to 36 teeth in each mandibular ramus. The marine tucuxi has more upper teeth and is larger than riverine specimens: total length can reach about 210 cm (with an extreme 220 cm reported) in the marine and about 152 cm in the riverine ecotype.

II. Ecology and Behavior

The marine tucuxi is found mostly in estuaries, bays, and other protected shallow coastal waters. It feeds mainly on demersal and pelagic fishes such as clupeids and scianids, and neritic cephalopods, shrimps, and flounders are occasionally taken. The riverine S. fluviatilis occurs in the main channel of rivers, tributaries, and lakes, usually avoiding rapids and not going into the flooded forest as the sympatric boto Inia gcojfren-sis. Its movements may be influenced by seasonal level fluctuation, using channels and lakes during rising and high waters while avoiding them during the low-water season.

Potential predators are the killer whale Orcinus orca and various species of coastal sharks for the marine ecotype and the bull shark Carcharhintis leucas in the Amazon. However, no record of such predation is known so far.

Figure 1 Relative little has been published concerning the Amazon dolphin called the tucuxi, which tends to occupy estuary and other shallow coastal habitats.

The tucuxi is a social dolphin often found in groups of 2 to 6 individuals. Groups of up to 50 or 60 specimens of the marine ecotype can usually be found. Large aggregations of up to 200 are reported in Bai’a de Sepetiba and around 400 individuals in Bai’a da Ilha Grande (Lodi and Hetzel 1998), on the southeastern Brazilian coast. Larger aggregations are usually engaged in cooperative feeding. Feeding occurs roughly in two ways: in pairs and cooperatively in larger groups or subgroups when different strategies are employed. During feeding activities marine tucuxis often associate with birds such as the brown booby Sula leucogaster; terns (Sterna spp.), frigate Fregata imgnificens, and kelp gull Larus dominicanus. In some locations, mixed flocks of up to 100 birds can be seen in such associations. In the Amazon, the tucuxi may feed occasionally in association with terns (Phaetusa simplex).

The presence of the tucuxi is recorded throughout the year in many coastal locations such as Bai’a Norte (South Brazil, coinciding with the species southernmost distribution limit), Cananeia estuary and Bai’a de Guanabara (both in southeastern Brazil), Bafa de Todos os Santos, and around Fortaleza (northeastern Brazil), as well as Bahia Cispata and Golfo de Morrosquillo (Colombia). Photoidentification studies in few of these areas have demonstrated that at least some animals are resident year-round for up to 7 continuous years (e.g., Flores 1999; Flores et al., 1999). The riverine tucuxi is very common in the Solimoes River and its tributaries as well as the Mamiraua area (Brazil), the Tara-poto River as well as Caballococha and El Correo lake systems (Colombia), and near Iquitos (Peru), to give some examples (Fig. 2). From scarce available data, abundance estimations in an area vary with the method employed. In Bai’a de Guanabara, it was calculated at between 69 and 75 individuals through photoidentification (Pizzomo, 1999) to 418 animals by line transect methods (Geise, 1991). It seems that the marine tucuxi is common but not numerous in such areas. In at least some locations the riverine ecotype is found in one of the highest densities found for cetaceans (Vidal et al., 1997).

Figure 2 Map of tucuxi distribtition.

Dive times are about 1.5 to 2 min with shorter surfacings every 5-10 sec in between. A variety of aerial behaviors may be displayed, such as full leaps, somersaults, flukes-up, spy-hopping, surface rolling, and porpoising. They do not bow ride but may surf in waves or wakes produced by passing boats. A lone, wild, and sociable animal, as well as a case of epimeletic behavior, was recorded along the Sao Paulo coast in southeastern Brazil. Tu-cuxis may interact with bottlenose (Tursiops truncatus) and Amazon river (Inia geojfrensis) dolphins. They have been engaged in apparent mating behavior with bottlenose dolphins off Costa Rica.

No mass stranding has been recorded, although dead animals usually wash ashore along its distribution, mainly resulting from incidental capture in fisheries.

III. Natural History

The breeding system of the species is polyandrous. with mating involving tactile contact and copulation occurring belly to belly. Calving is year-round in most of the coastal species’ distribution and in October-November during low-water season for the freshwater ecotype. Gestation is estimated to be around 11 to 12 months with calves ranging from 90 to 100 cm (marine ecotype) and around 10 months and 71 to 83 cm (riverine ecotype). The calving interval is believed to be 22-23 months (through photoidentification data). According to tooth growth layer groups, the lifespan can reach 30 and 35 years for marine and riverine ecotypes, respectively. Natural mortality rates are unknown.

IV. Interactions with Humans: Threats and Conservation

The species have not been exploited commercially, although incidental mortality in local and commercial fishing gear such as gill nets and seines are the main direct threat to tucuxis. In some localities they are killed on occasion for shark bait or human consumption, although tucuxis have protection from myths and legends, especially in the Amazon. There, their genital organs and eyes have a small market as love charms. Dams and hydroelectric power facilities may isolate populations and interrupt fish migration as well as reduce fish abundance. Gold mining with mercury, destruction of mangroves and salt marshes, water pollution, and boat traffic are other potential threats. The recent events of hand feeding and the short-term behavioral effects caused by tourism boats also deserve concern.

Tucuxis die easily due to capture stress during transportation or handling. Some animals, though, have been held in captivity, where they exhibit rare aerial behavior and common aggression toward male tucuxis and other species. Today just a few tucuxis are kept in European facilities.