Territory and territoriality widely refer to the exclusive use of space by individuals or groups, entailing both spa-Vtial defense and advertisement. Such terms have been applied to diverse animal species (e.g., octopuses, insects, primates) and functions (e.g., nesting, mate attraction, feeding) over a broad range of scales in space (millimeters to kilometers) and time (seconds to years). Such broad ranges of biological forms and functions cannot be encompassed by a single definition. Definitions that apply to selected taxonomic groups or functions of interest and over scales of space and time relevant for those groups or functions are best.

In this article, “territoriality” and “territorial behavior” refer to behavior associated with obtaining, defending, or advertising occupancy of space. Of course when two animals interact ago-nistically, they always do so within a spatial framework, but social interactions by themselves do not constitute territorial behavior. “Territoriality” connotes something other than just behavior relative to the interacting animals themselves or to their arbitrary spatial positions, such as (1) specific spaces relative to other individuals or to the external physical environment or (2) particular spatial features (e.g., a haul-out ledge). Nevertheless it is usually impossible to draw a strict distinction between defense of a space and resources within that space for all situations because species (or individuals, age classes, or social classes) that are usually viewed as “nonterritorial” like walruses (Odobenus rosinanis) or elephant seals (Mirounga spp.) exhibit territorial-like behavior in some settings, and vice versa for “territorial” species like fur seals and sea lions (Otariidae; “otariid” hereafter). Therefore, in this article the application of the definition given earlier is broad.

Territorial size, clarity and constancy of territorial boundaries, the medium in which territories occur, and functions of territories are interwoven. Cetaceans, sirenians, and polar bears (Ursus maritimus) exhibit little behavior suggesting the exclusive use of space defended or advertised by individuals or groups, but territorial behavior is clearly expressed in sea otters (Enhydra lutris) and most pinnipeds.

I. Development of Territorial Behavior

Sexual differences in behavior appear early in life in otariids. Male pups are more aggressive than females and engage in play fighting and boundary displays (Section V) within the first few weeks of life. Young otariid males of all ages engage in such behavior commonly in their interactions with one another, both inside and outside the breeding season. Juvenile and subadult walruses (including calves), recently weaned elephant seals, and juvenile and subadult harbor (Phoca vitulina) and gray (Halichoerus grypus) seals also show sexual differences in social behavior, with males spending more time play fighting with one another.

Territorial males of most otariid species appear to try to keep females on their territories by herding (Section V). Herding behavior appeal’s early in life, and male pups preferentially direct this behavior toward female pups (e.g., Australasian fur seal, Arctocephalus forsteri). Herding is also expressed by nonterritorial males during tire breeding season, e.g., when they encounter females moving toward or away from breeding aggregations. In all otariid species, numbers of nonterritorial males (including subadults) may rush simultaneously into (“raid”) breeding aggregations and herd or interact with females in various ways before they are chased away by territorial males [raiding male

South American sea lions (Otaria flavescens) may achieve some direct reproductive benefits]. In species that frequent the colony site year-round (e.g., Australasian fur seal), juvenile and subadult males herd pups and young juveniles occasionally at various times outside the breeding season. An extreme form of this behavior occurs in the South American sea lion, in which nonterritorial males frequenty carry pups away in their mouths following raids on breeding sites. They carry the pups into the ocean (where they may drown) and then to nonbreeding areas where the males herd and mount them, sometimes over several days; pups usually die.

II. Territorial Functions

Nonbreeding pinnipeds engage in many agonistic social interactions in disputes over resting places at haul-out and breeding colony sites. Nonbreeding individuals may also favor and defend particular sites during the breeding season (e.g., otariids, harbor seals). Despite their relatively minor costs and benefits, such airborne interactions constitute territorial behavior in the sense used in this article and employ similar motor patterns to those used in better known and more dramatic examples of territoriality by breeding animals. In otariids, breeding females compete with one another for favored or habitual sites for resting or for nursing the young, and older pups similarly interact agonistically with one another or displace younger pups from favored rest sites.

The best known and most dramatic forms of territoriality in marine mammals are shown by breeding adult males. Male sea otters, otariids, and some seals (Phocidae; “phocid” hereafter) establish territories seasonally where females give birth and enter estrus, or to attract estrous females that have given birth. Sometimes territoriality by male pinnipeds is expressed only after females haul out at a breeding site [e.g., Hooker's sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri), gray seal], and males may also change locations facultatively in response to female movements, attend and defend isolated lone females, or even defend female carcasses (Fig. 1). However, the ultimate explanation for male territoriality is to obtain access to estrous females, thereby increasing male reproductive success.

III. Territoriality in Space

Discrete, clearly defined territories are most apparent on small temporal scales, in situations of crowding, in species that have good locomotory abilities so they can efficiently patrol or defend their territories, or where environmental features (e.g., topographical irregularities) occur that can be used by the animals to demarcate territories. Such conditions rarely occur in the lives of cetaceans (especially open-ocean species) so territoriality is rare or nonexistent in that group. River dolphins, with their spatially restricted distributions, or species that feed on concentrated prey that are sedentary or spatially predictable may be exceptions. In Scotland’s Moray Firth, year-round resident common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) may be territorial and exclude seasonal (winter) conspecific visitors from deep waters, which are most favorable for feeding.

Most species of otariids breed on crowded colony sites and hold small territories; territories of male Hooker’s sea lions are often no more than 3 m in diameter, for example (about 30 m2 in area), and some northern fur seals (Callorhinus iirsinus) hold territories that are little larger in diameter than a male’s body length (Fig. 2). Larger territories occur in related species (e.g., about 200 m2 in male Steller sea lions, Eumetopias juba-tus). Small aquatic territories are held by some male Juan Fernandez fur seals (Arctocephalus philippii) adjacent to breeding aggregations, and walruses hold small aquatic territories adjacent to mixed herds on ice. In general, however, aquatic territories are large; >100 in in length in some male Weddell seals (Leptonychotes weddellii), up to 1 km across in male sea otters, and up to 10 km across in some male harbor seals; aquatic territories are commonly not contiguous (Fig. 3).

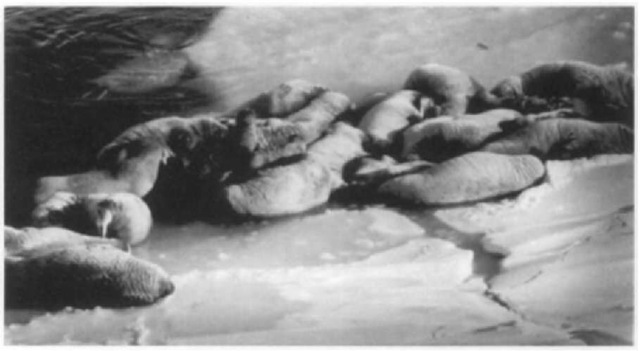

Figure 1 Defense of space and of females is connected intimately in male marine matninals: adult male California sea lion defending carcass of female.

Phocids are specialized for aquatic locomotion, so their locomotion on land is slow and energetically costly. Unsurprisingly, territories in land-breeding populations of gray seals exhibit extensive overlap (Fig. 4). The poor locomotory abilities and large size of the two species of elephant seals usually preclude territoriality, although in small confined areas (e.g., coves) the defense of space and of females amounts to the same thing.

Rocks, fracture fines, and other natural features often enable precise delimitation of otariid territories. If such features are present, then parts or all of a territory’s boundaries can be discrete. Territories that are partly or completely on featureless terrain (e.g., sandy beaches) cannot be clearly delimited by territory holders, so shifts in size, shape, and even location are common. Aquatic territories may include or be adjacent to prominent geological features or landforms. In species that breed in association with ice, underwater features of ice, or fractures or leads in ice, may be important in determining territorial density, size, or shape (Fig. 3A). In the walrus, male territories are established in the water adjacent to mixed herds on ice (Fig. 5). The ice may be stable land-fast ice (e.g., parts of Canada’s arctic archipelago) or unstable drifting pack ice (e.g., Bering Sea). Walrus territories are ill defined and variable due to variability in ice and herd size and dispersion.

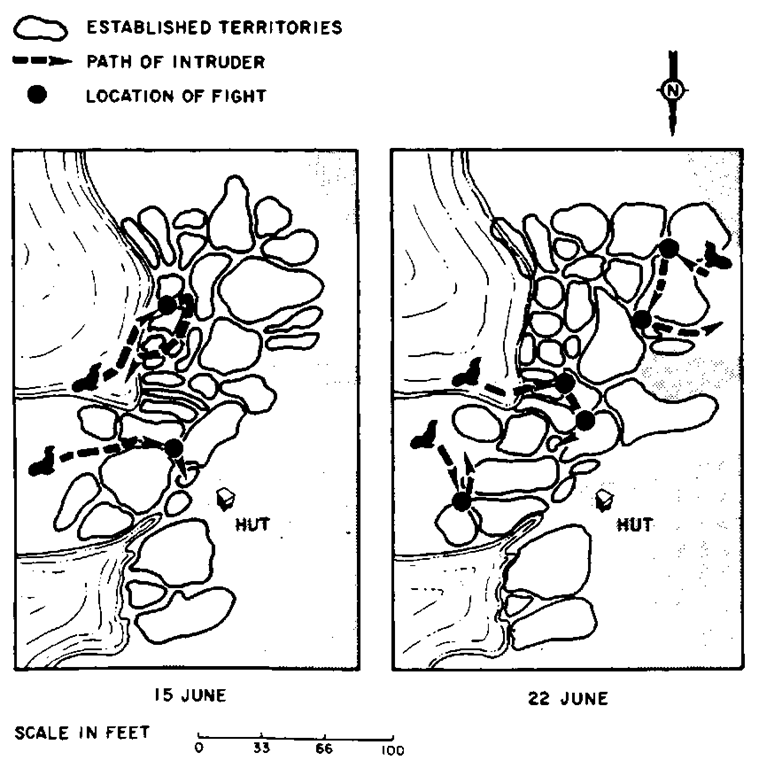

Figure 2 Small, well-defined breeding territories occur in some species (northern fur seal). Territories are shown as slightly separated for clarity. Routes of entry into the existing territorial structure by males that obtained or failed to obtain territories are shown.

IV. Territoriality in Time

In otariids. size and shape of territories in shoreline locations are often influenced by the tide. Shoreline territories may alternately be above and partly under water and may be temporarily abandoned at high water levels (e.g., high tides, storms). Inland territories, especially those that lack pools in which males can cool themselves, may be abandoned in the heat of the day [e.g., Afro-Australian fur seal (Arctocephalus pusillus), Juan Fernandez fur seal]. Walrus territories change in size, shape, and dispersion due to ice movements, amalgamation, and breakup.

Absence of females from their territories sometimes leads to territorial desertion by male otariids, but more commonly males attempt to acquire a new territory where females are present. In Hooker’s sea lion, males establish territories several times during the breeding season in response to movement of the female aggregation down the beach. Southern sea lion males defend conventional territories (i.e., defense of space) early in the breeding season but gradually change to defense of females as the season progresses.

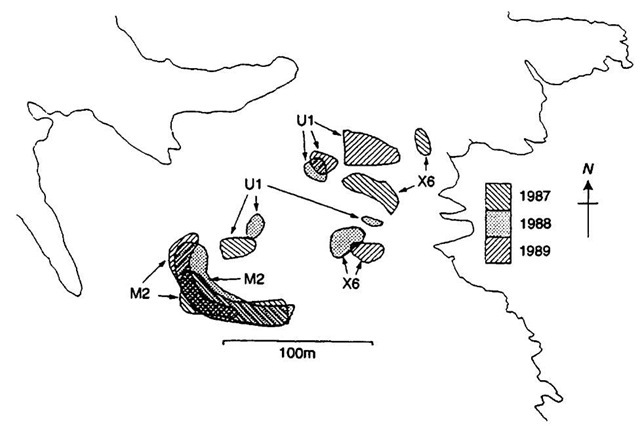

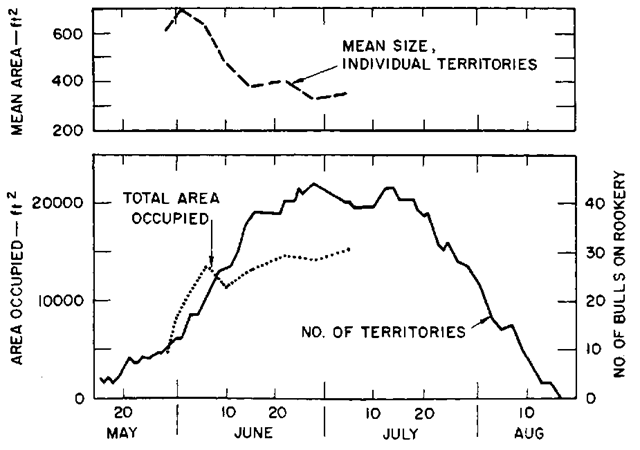

Territories of most or all otariids are most clearly defined at the peak of breeding, when territorial density is highest and territorial size is smallest (Figs. 2 and 6). Male otariids habituate to neighboring males and engage in fewer and less aggressive interactions with neighbors over time. A similar effect even occurs between males that held neighboring territories in the previous year (e.g., Steller sea lion). On Sable Island, Nova Scotia, some male gray seals abandon their territories and then establish new ones on the island some distance away (up to several kilometers) within the same breeding season; smaller scale changes within seasons also occur (Fig. 4).

Long-term fidelity to territorial locations has two components. First, there is a tendency for males to return to breed near the site of their birth (philopatry). Second, males exhibit site fidelity by tending to return in successive years to where they first established a territory. Both forms of site fidelity are known in otariids and terrestrially breeding phocids (elephant seals, gray seals). Site fidelity is especially strong in otariids; for example, one male Antarctic fur seal (Arctocephalus gazclla) returned to within 1 m” of previous territorial locations over seven successive breeding seasons. Males exhibit breeding-site fidelity even in phocids that breed in association with fairly stable land-fast ice [e.g., ring seal (Pusa hispida), Weddell seal]. In contrast, some individual male gray seals in eastern Canada have been observed in different breeding seasons at terrestrial breeding sites and at sites where breeding takes place on ice. Male sea otters hold territories in the same location for up to seven successive years. The combination of philopatry with general site fidelity suggests that kin may breed in close proximity to one another in otariids, gray seals.

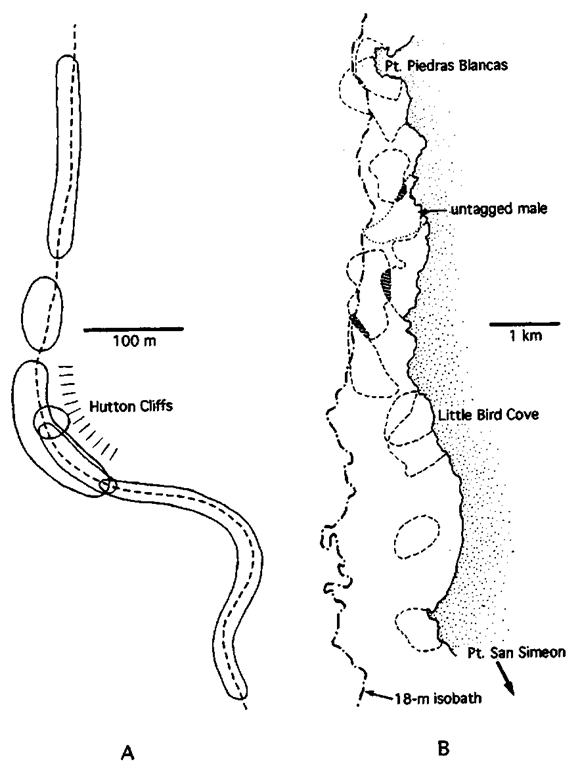

Figure 3 Aquatic territories are typically large and overlap, but environmental features are important: Weddell seal (A) and sea otter (B). Six territories are outlined in A; the dashed line in A indicates a tidal crack in the ice on which territories were centered (the two small territories by the Hutton Cliffs were less well documented than the others). Eleven territories (10 of tagged males) are shown in B (note placement relative to water depth); overlap of concurrently held territories is indicated by hatching.

V. Obtaining, Defending, and Advertising Territories

Dramatic and potentially injurious fights between males occur in all territorial species, particularly when new males at tempt to establish themselves. Because severe injuries or (rarely) death can result, fighting is undertaken only in specific circumstances; instead, most interactions between competing or neighboring males involve rich optical, acoustic, tactile, or chemical displays. In the northern fur seal, for example, only about 1% of encounters between territorial males involve actual fights.

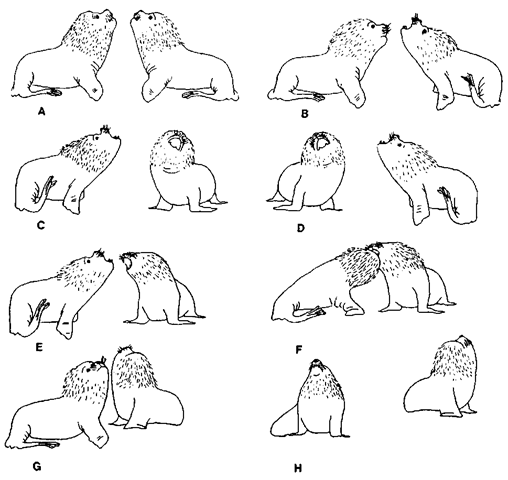

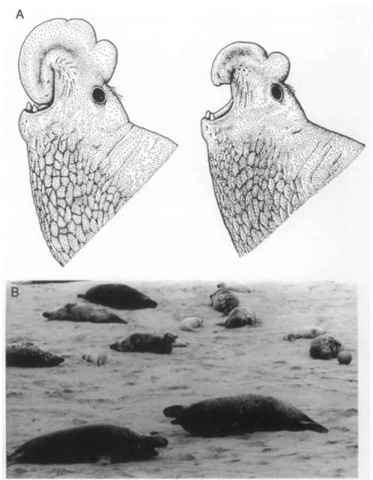

The distinctive appearance of adult male otariids is communicatively important in the context of territoriality. For example, in contrast to females or young males, adult male California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) are much darker than females or young males, and adult male South American sea lions have distinctive manes. Some of the many optical displays of otariids are relatively passive and undirected (e.g., a distinctive nose-up upright resting posture). Most optical displays are directed toward specific individuals and involve movements, such as distinctive head-and-neck swinging locomotion, or rapid and complex sequences of motor patterns, including feints, oblique stares, sprawls, and facial expressions, in displays between neighbors across territorial boundaries (Fig. 7). Elephant seals and gray seals have specialized facial features used in displays over various distances (Fig. 8). In underwater communication, optical displays cannot effectively employ fine features like facial expressions so must rely on general patterns of pelage or on whole body movements or postures.

Figure 4 Movements within and site fidelity between years are important in spacing systems of most or all territorial marine mammals: territorial male gray seals on North Rona, Scotland.

Acoustic displays can travel long distances and are energetically inexpensive to produce, so unsurprisingly are important in territorial displays of almost all marine mammal species. Not all such displays are vocal. Male sea otters patrol their territory while swimming on their backs and kicking vigorously, diereby generating loud splashing sounds (this display probably represents ritualized swimming). In otariids and elephant seals, loud airborne distinctive vocalizations are given by breeding males. Underwater “songs” are well known in walruses and phocids, including Weddell and bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus). Loud sounds are probably designed to signal to a range of listeners (nonterritorial adult or subadult males, other territorial males, females), although in otariids they generally have been interpreted as a communication of “threat” among territorial adult males. Numerous medium- or short-range vocalizations are also given by territorial males; they are often directed to ward other males, but are audible hence informative to all nearby animals. There are many unanswered questions about acoustic communication in both territorial and nonterritorial marine mammals; e.g., why do male sea otters and polar bears lack loud vocalizations for long-distance advertisement and why are male Hookers sea lions, gray seals, and monk seals (Monachus spp.) virtually silent?

Figure 5 Walruses hold small, dynamic aquatic territories adjacent to mixed herds on ice: territorial male (in water) adjacent to mixed herd in central Canadian arctic.

Figure 6 Territorial size is smallest and defined most clearly in the peak of breeding: seasonal trends in territorial size in the northern fur seal.

Figure 7 Complex sequences of motor patterns typify short-range communication between territorial male marine mammals: behavioral sequence (A-H) in representative “boundary display” between male South American sea lions.

Figure 8 General appearance and special structures are important aspects of displays between territorial marine mammals: (A) profiles of adult male northern (left) and southern (right) elephant seals (Mirounga leonina) with nasal hoods expanded (used in various displays) (from Briggs and Morejohn, 1976) and (B) adult male gray seals (in foreground) in antiparallel display on a breeding colony (Sable Island, Nova Scotia).

Chemical communication is probably important in all territorial species of marine mammals although is virtually unstudied. Facial glands are unknown in sea otters but the species has well-developed anatomical (neural) characteristics for olfaction, and individuals often actively smell the air. Glands on the face (many associated with facial vibrissae) occur in otariids, walruses, and phocids and are known to vary seasonally in size and secretory activity in some species. Male otariids emit distinctive odors during boundary displays between neighbors, perhaps from the oral cavity, and have distinctive body odors during the breeding season, but the anatomical source and functions of the smell are unknown. Breeding male ringed seals hold underwater (and underice) territories that are near but do not overlap with areas used by breeding females. During the breeding season, adult males of this species acquire a strong odor, which is the origin of terms like “tiggak” ( “stinker”) among Inuit and “gasoline seal” among trappers. Male ringed seals may actively deposit secretions from facial glands on entrances to their breathing holes and subnivean (“below snow”) resting lairs, and within the latter.

The roles of taste or use of the vomeronasal organ (VNO) are unknown, but otariids commonly exhibit slow, repeated tongue extrusion following agonistic displays (e.g., boundary displays or fights involving males; females, juveniles, and even pups also express the behavior), suggestive of behavior of other mammals that are known to use the VNO in chemical communication (at the very least, tongue extrusion is a conspicuous optical signal and likely has become ritualized as an optical display).

Tactile communication is also important but is essentially unstudied in marine mammals. Breeding males of all species engage physically and contact one another extensively in biting, wrestling, or pushing. Male sea otters often try to bite the opponent’s penis, and fractured bacula (penis bones) of mature males are relatively common in the species. In phocid species that fight aquatically, the rear flippers (necessary for aquatic locomotion) are bitten and injured frequently in fights; walruses use the tusks in physical contests in which males face each other, mainly at or just below the water surface. Physical contests in otariids, walruses, elephant seals, and gray seals on land take place with the animals facing each other, so most pushing, striking, biting, and so on involve anterior body parts.

VI. Costs of Territoriality

Competing for and holding territories are highly competitive and entail risks and costs. In all marine mammal species, physical and behavioral maturation in males is a slow process and differs from females. Males typically attain physiological sexual maturity years before they begin to compete for territorial status because they are neither physically large nor behaviorally experienced enough to effectively obtain and maintain territories.

Costs and risks of competition for territorial status are partly energetic but include dangers of suffering severe physical injury (the relative importance of these factors varies across species). Energetic considerations increase in importance after territorial status is achieved. Energetic costs are borne through advertisement and display, fights, herding, patrolling, alertness, and so on. Males reduce their food intake (e.g., harbor seals) or fast completely (e.g., otariids, elephant seals, gray seals) when they are territorial. The combined effects of reduced food intake or fasting plus high energetic expenditure are large. On average, territorial male northern fur seals fast and do not drink for about a month (maximum 87 days) and decline by about a third in body mass over that time. This loss in body mass is equivalent to about 0.7% of initial body mass per day, a level exceeded by several other species: Antarctic fur seals (0.8%), gray seals (0.9%), and the aquatically territorial Weddell seal (0.8%). The large northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris-, ca. 1700 kg) and the harbor seal, in which breeding males do not fast completely, lose less (about 0.4% per day), but overall costs are high in all species and are extreme in some individuals (one territorial male harbor seal lost 30% of his initial body mass).

Territorial male marine mammals must balance the need to economize energetically widi the need to be vigilant, defend their territories, and effectively advertise territorial occupancy and their own physical attributes. Studies of time-activity budgets have revealed that territorial males spend much time at rest and little time in the most dangerous or energy-demanding activities such as fights.

Mortality rates of males are similar to those of females until the age of social maturity is attained. Beginning then, mortality rate of territorial males surpass those of females, sometimes by several times.