The susu and bhulan, Platanista gangetica gangetica and P. g. minor: are two river dolphins of the South Asian subcontinent. Some scientists dispute the existence of one species and consider them to be separate, P. gangetica and P. minor (Pilleri et al., 1982). A variety of vernacular names are used for the susu and bhulan, mostly connoting the sound made during respiration. For the susu, these include swongsu and sns matsya (matsya = fish) in Nepali, soonse and snnsar in Hindi, hiho and shihii in Assamese, and shushuk and sishu-, foo-, or hungmaach (riwach = fish) in Bengali. For the bhulan, these include bhoolun and sisar.

I. External Appearance

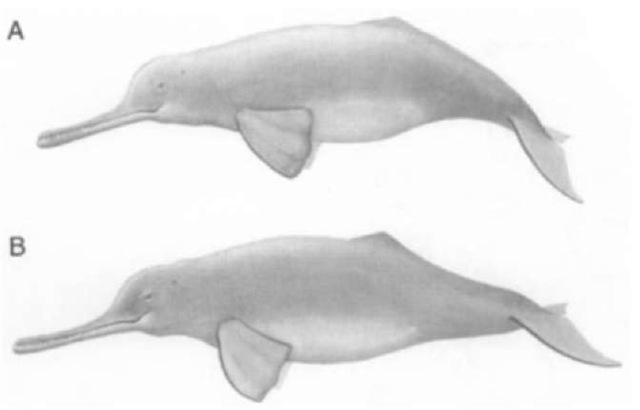

The subspecies are nearly identical in external appearance (Fig. 1). Their body is supple and robust, attenuating behind the dorsal fin in a narrow tail stock. Coloration is gray overall, becoming blotchy with age. Bellies of young animals are lighter and often have a pinkish hue. The dolphins have a long snout that becomes wider at the tip. Adult females generally have a longer snout, which sometimes curves upward and to one side at the tip when particularly long. Their numerous narrow pointed teeth are curved inward and become longer toward the distal end of the mandibles, becoming visible in larger individuals. Teeth become peg-like in older individuals from wear and accumulation of the cement layer. Their eyes are extremely small and visible as pinhole openings slightly above the upturned mouth. The external auditory meatus is larger than the eye opening and located slightly above it, a unique arrangement among odontocetes. The blowhole is a small slit oriented longitudinally, which is a rare but not unique configuration among cetaceans. A distinct median ridge begins anterior of the blowhole and bisects a convex melon, which becomes less rounded as the dolphin approaches adulthood. The dorsal fin is a low triangular hump with a slightly defined knob at the apex located about two-thirds of the body length posterior of the melon. Broad flippers are squared-off at the end with a crenellated margin, and the arm and hand bones are visible beneath the taut dorsal surface. Flukes are broad with a concave margin and distinct median notch. The opening for male genitals is located much closer to the umbilicus in relation to the anus when compared with most other cetaceans.

Figure 1 (A) The susu (Platanista gangetica gangetica) and (B)bhulan (P. g. minor) are river dolphins with long narrow snouts reminiscent of gharial crocodilians (Gavialis gangeticus) that are also found in some of the same rivers. These endangered taxa were once hunted, a practice now prohibited. Entanglement in gillnets, water development, pollution, and occasional poaching are adversely affecting the survival of this species.

II. Taxonomy

Primitive features, such as intestinal cecum, and weak evidence from the nucleotide sequence of the cytochrome b gene suggest that Platanista may be a sister taxon to all other extant odontocetes (Rice, 1998). Although the superfamily Platanis-toidea was previously considered to include three other mono-typic genera—Pontoporia, Lipotes, and Inia (Kasuya, 1973; Zhou, 1982)—the genus Platanista is now recognized as the only extant member of the taxon (Rice, 1998). Pilleri et al. (1982) recognized two species of Platanista based on differences in the prominence of the nasal crests, caudal height of the maxillary crests, length of the lower transverse processes of the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae, blood protein composition, and free-esterified cholestrin ratio in the lipids. Their arguments were unconvincing due to the small sample of adult specimens examined and the absence of statistical analyses (see Reeves and Brownell, 1989). Based on differences in tail lengths, Kasuya (1972) proposed that the susu and bhulan be considered subspecies; this was followed by Rice (1998).

III. Habitat

Susus and bhulans generally occur in eddy countercurrents downstream of channel convergences and sharp meanders, and upstream and downstream of mid-channel islands. They also occasionally occur in countercurrents induced by engineering structures such as bridge pilings and groynes. The affinity of Platanista for countercurrents is probably greatest in upstream tributaries where productivity is especially clumped and strong downstream currents restrict occupancy to the hydraulic refuge these areas provide (see Smith, 1993: Smith et al, 1998).

IV. Population and Distribution

Although no rigorous range-wide surveys have been conducted, the aggregate populations of susu and bhulan are believed to number in the low thousands and few hundreds, respectively (Smith and Reeves, 2000). A map of historical distribution, charted by the 19th century British naturalist John Anderson (Anderson, 1879), shows the bhulan occurring throughout the Indus River mainstem and in the Sutlej, Ravi, Chenab, and Jhelum tributaries and shows the susu occurring throughout the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Megna and Karnaphuli river systems in Nepal, India, and Bangladesh. Anderson (1879) stated that the range of both species was only limited downstream by increasing salinity in deltas and upstream by rocky barriers or insufficient water. Their distribution has shrank considerably since then, largely due to water development, which has blocked dolphin movements and degraded their habitat.

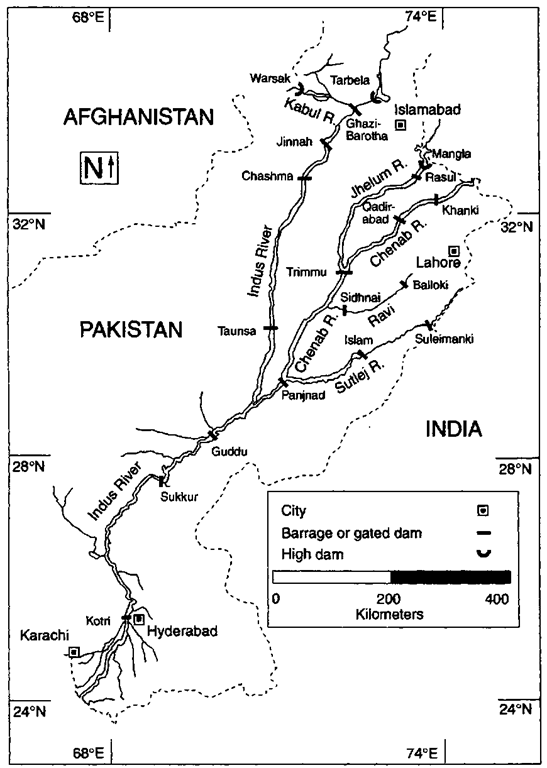

Bhulans currently occupies less than 700 kin of the Indus mainstem (about one-fifth of the historic range), fragmented into three subpopulations by the Chashma, Taunsa, Guddu, and Sukkur barrages (Fig. 2; Reeves and Chaudhry, 1998). The largest sub-population is located at the downstream end of the dolphins’ range, between the Guddu and Sukkur barrages, with a reported count of 458 individuals (Mirza and Khurshid, 1996). Numbers decline progressively in upstream segments, despite their progressively larger geographical size. Counts of 143 and 39 individuals were reported between the Taunsa and Guddu and the Taunsa and Chasma barrages, respectively (Mirza and Khurshid, 1996). A few scattered individuals may still occur upstream of the Chashma barrage in the Indus and downstream of the Triinmu, Sidhnai, and Panjnad barrages in the Chenab, Ravi, and Sutlej rivers, respectively (Reeves et al, 1991). A few bhulans may also stray below the Sukkur barrage, but these animals are lost to the overall population and have little chance of surviving due to lack of water.

Figure 2 Map of the Indus river system of Pakistan showing dams and barrages that have fragmented the population of bhulans and degraded their habitat.

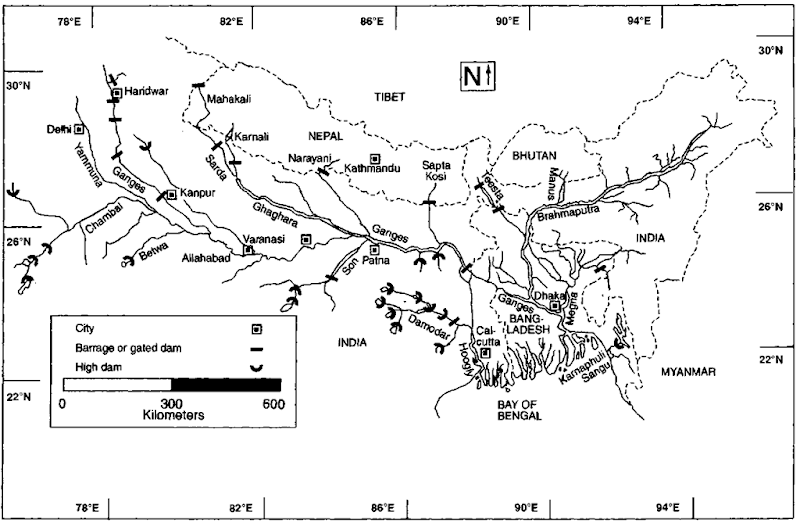

Historically, susus were found in the Ganges River as far upstream as Haridwar, about 100 km above their current range, and in the Yamuna River year round as far upstream as Delhi, probably about 400 km above their current low-water range (Fig. 3; Sinha et al, 2000). In the Ganges mainstem, there are four extant subpopulations isolated between barrages. In the northern tributaries of the Ganges, of the six subpopulations that have been isolated above or between barrages, three have been extirpated (Gandak River above the Gandak barrage and Sarda River above the upper and lower Sarda barrages) (Sinha et al, 2000) and one reduced to insignificant numbers (Kosi River above the Kosi barrage) (Smith et al, 1994). In the Son River, a southern tributary of the Ganges, a small population of susus has been isolated above the Indrapuri barrage, and the dolphins no longer occur during the dry season for about 100 km below the barrage until the Ganges confluence (Sinha et al, 2000). In southern Bangladesh, susus were documented in the Sangu River (Ahmed, 2000), which is connected to the Karnaphuli by the Sikalbaha-Chandkhali channel. There are occasional reports of dolphins remaining in the reservoir behind Kaptai Dam, but recent surveys produced no sightings.

V. Internal Anatomy

A. Bones

An extraordinary feature of the skull of Platanista is the projection of a maxillary crest, upward and forward, covering an air sinus that leads to the tympanic cavity. The crest slants to the left, which makes the skull among the most asymmetric of all odontocetes. Other skull features unique to Platanista include that the palatine is found in the nasal tube and that the pterygoids are external on the palate and enter the temporal fossa (Reeves and Brownell, 1989). The mandibular symphysis is laterally compressed, slightly upturned toward the end, and it constitutes as much as two-thirds the mandible length of adult females and a little more than half of adult males (Reeves and Brownell, 1989). Cervical vertebrae are unfused, allowing considerable neck movement. Postcranial skeletal features unique to Platanista include the location of costal facets of the thoracic vertebrae on the posterior margin of the centrum, a thicker ulna than radius, and the absence of ulnare and pisiform bones in the flippers.

Figure 3 Map of the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Megna and Karnaphuli-Sangu river systems of Nepal, India, and Bangladesh showing dams and barrages that have fragmented the popidation of susus and degraded their habitat.

B. Organs

The presence of a cecum between the large and the small intestines, a penis with erectile side lobes, nasolaryngeal air sacs that form a diverticulum of the eustachian tube, and a primitive and relatively unlobulated kidney distinguish Platanista from other odontocetes. Compared to other dolphins, their brain is small and neocortical development is low; however, subcortical components associated with acoustical functions are well developed. Their small eyes lack a crystalline lens, giving the dolphins a reputation for being blind, but their retinas do have light-gathering receptors (Herald et al, 1969).

VI. Life History

Males attain sexual maturity at a body length of about 170 cm and physical maturity at 200-210 cm. Females attain sexual maturity at similar or slightly larger body lengths but physical maturity at about 250 cm. The generally larger rostrum ol females accounts for this sexual dimorphism, which becomes evident at a body length of about 150 cm. Length at birth is estimated to be about 70 cm. Gestation lasts approximately 1 year, with possible peak birthing seasons in early winter and early summer. Young begin feeding on small prey at about 1 or 2 months and are weaned within a year (Kasuya, 1972).

VII. Behavior and Sensory Abilities

In 1968, three female bhulans were taken to the Steinhart Aquarium in San Francisco, where all died within 7 weeks. During the 1970s, the Swiss neuroanatomist Georgio Pilleri kept a total of seven bhulans in his institute at the University of Berne until they all died within a few years. Studies of these dolphins revealed exceptional aspects of Platanista behavior and sensor)’ abilities. The dolphins vocalize almost constantly and swim on their sides in vertical circles. The dolphins continuously emit trains of high-frequency (15-150 kHz) echolo-cation clicks, interrupted by short pauses of 1-60 sec (Herald et al, 1969). The click trains are focused in two highly directional fields, the dorsal one emitted directly from the melon and the ventral one reflected downward by the maxillary crest, with an acoustic “scotoma” in between (Pilleri et al., 1976). During a dive, the dolphins spin 90° on their lateral axis and position their head down, sweeping it back and forth in a scanning motion, while trailing one flipper along or slightly above the bottom. Shortly before surfacing, the dolphins reverse their spin and surface close to their original position and orientation.

In the wild, susus and bhulans are observed alone or in clusters of 2-3, but occasionally as many as 20 individuals. With the exception of mother-young pairs, the attracting force for these clusters may be more related to the patchy distribution of prey and hydraulic refuge than to survival or reproductive advantages gained by close social affiliations. Susus have been observed surfacing just inside of the upstream end of counter-current boundaries where the eddies become aligned with main flow. Surfacing at this location may allow the dolphins to minimize energy outputs while monitoring foraging opportunities in the mainstream flow and center pool of the countercur-rent (Smith, 1993).

VIII. Threats and Conservation

Both subspecies are classified by the IUCN as endangered. Perhaps the most significant threat to their survival is the existence of numerous dams and barrages that have severely fragmented populations and reduced the amount of suitable habitat. Dams are absolute barriers to dolphin movements. Subpopulations trapped above barrages are believed to lose dolphins when they move downstream during high water while the barrage gates are open. These dolphins probably cannot return due to strong hydraulic forces between the gates while they are open. This apparent involuntary attrition exasperates normal biological problems faced by small isolated populations. Water diverted by barrages, generally for irrigation and flood control, and abstracted by surface pumps and tube wells also results in dolphins competing with humans for the actual substance of their environment: fresh water. During the low-water season, the Indus and Ganges rivers become virtually dry downstream of the Sukkur and Farakka barrages, respectively.

Deliberate killing of bhulans for meat and oil was a traditional practice until at least the early 1970s (Pilleri and Zbinden, 1973-1974). Hunting is now banned but poaching still occasionally occurs (Reeves and Chaudhry, 1998). Susus are killed by “tribals” in the upper Brahmaputra for their meat and by fishermen in the middle reaches of the Ganges for their oil, which is used as a fish attractant (Smith and Reeves, 2000). Similar to all cetaceans, the susu and bhulan are threatened by entanglement in fishing gear and vessel collisions. Their preferred habitat is often in the same location as primary fishing grounds and ferry crossings, which puts the dolphins at increased risk. The problem of accidental killing in fisheries will undoubtedly worsen as the demand for fish and fishing employment increases. Pollution may also be affecting the survival of both species, especially considering the decline in the flushing benefits of abundant water and the aggregate distribution of river dolphins in areas of intensive human use. As top carnivores, the dolphins are particularly vulnerable to persistent contaminants (e.g., PCBs and DDTs), some of which are banned or strictly regulated in more developed countries but widely used in industry and agriculture of south Asia.

In 1974, the government of Sindh declared the Indus River between the Sukkur and Guddu barrages a dolphin reserve and the government of Punjab prohibited deliberate killing (Reeves et al., 1991). Enforcement of these measures seems to have stopped the rapid population decline of the bhulan reported by Pilleri and Zbinden (1973-1974). The susu was perhaps the first cetacean to receive official protection from hunting when it was listed as a protected species in the Moral Edicts of King Asoka in India more than 2000 years ago. Susus currently receive legal protection from deliberate killing in all range states. The Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary, Bihar, India, located between Sultanganj and Kahalgaon in the mainstem of the Ganges was designated as a protected area for dolphins in August 1991. In a few smaller tributaries, susus receive nominal protection by virtue of small portions of their habitat being included in or adjacent to national parks and sanctuaries.