The spinner dolphin, Stenella longirostris (Gray, 1828), is the most common small cetacean in most tropical pelagic waters. It can be seen at a great distance as it spins high in the air and lands in the water with a great splash.

It also commonly rides the bow wave of boats and thus can be observed closely.

I. Characters and Taxonomic Relationships

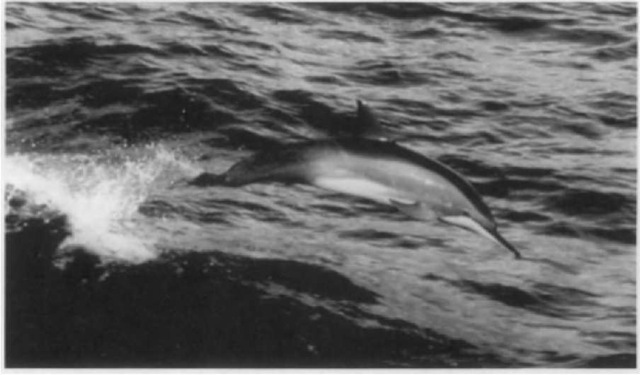

The spinner dolphin can be identified externally by its relatively long slender beak, color pattern, and dorsal fin (Fig. 1). The color pattern in most regions is three-part, consisting of a dark-gray cape, light-gray lateral field, and white ventral field. A dark band of even width runs from the eye to the flipper, bordered above by a thin light line. The rostrum is tipped with black or dark gray. In the eastern and Central American subspecies of the eastern tropical Pacific, S. I. orientalis and S. I. centroameri-cana (Fig. 2), contrast between the cape and the lateral field is very faint to absent, and the ventral field may be restricted to discontinuous axillary and genital-region patches. Various intermediate color patterns are exhibited by “whitebelly spinners in a broad zone of hybridization between the eastern form and the more typically patterned Gray s spinner dolphin, S. I. longirostris, in the Central and South Pacific. The dorsal fin in adults in all regions is basically triangular, varying from a slightly falcate right triangle to an erect isoceles triangle. In the adult male of the eastern and Central American subspecies the dorsal fin may lean slightly forward, appearing to “be on backwards.” This is correlated with the presence of a large postanal ventral hump. Both the dorsal fin and the hump appear to be sexual displays, probably important in male-male or male-female communication or both. In calves and juveniles in all regions, the dorsal fin is on average more falcate than in adults.

Sexually mature adults examined ranged from 129 to 235 cm (n = 1824) and weighed 23-78 kg in = 33).Males are on average slightly larger than females in body size and most skull characters.

The spinner dolphin may be confused in the tropical Atlantic with the endemic Clymene dolphin, S. clymene, which is very similar in appearance and has been observed to spin, although not as acrobatically as the spinner dolphin. In the Clymene dolphin, the beak is relatively shorter, the flipper band narrows anteriorly, the lower margin of the cape dips lower toward the ventral field (in the spinner the cape and ventral-field margins are parallel), and there is usually a dark “moustache” mark on the upper side of the beak that has only rarely been observed in spinner dolphins.

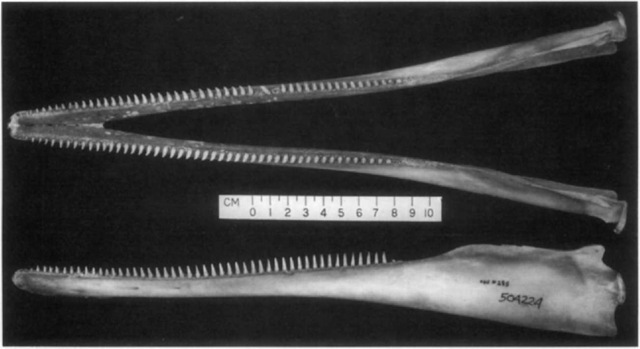

The skull (Fig. 3) can be confused with those of S. coeruleoalba, S. clymene, and Delphinus spp.: all have a relatively long and narrow dorsoventrally flattened rostrum, a large number of small slender teeth (about 40-60 in each row), and medially convergent premaxillae and sigmoid ramus.It differs from Delphinus in lacking strongly defined palatal grooves. The rostrum is narrower at the base than in S. coeruleoalba (57-84 mm vs 93-120 mm). It overlaps S. clymene in all skull measurements and tooth counts, but the skull (335—464 111111 long in 112 adults) is proportionately longer and narrower. The vertebral count is 69-77 {n = 90).

The spinner dolphin is a member of the subfamily Del-phininae sensu stricto (LeDuc et al, 1999). Morphologically and behaviorally it is most similar to the Clymene dolphin, but in a cladistic phylogenetic analysis based on cytochrome b mtDNA sequences it was not closely linked to that species, which was the sister species of the striped dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba (LeDuc et al, 1999). The morphological similarly between spinner and Clymene dolphins could be an instance of plesiomorphy (similarity through retention of primitive characters), but the correlated spinning behavior would seem to be highly derived, a probable synapomorphy. This puzzling discordance between molecular and morphological/behavioral characters shows the need for further molecular and morphological investigation; a hybrid origin of S. clymene has been suggested as one possible explanation (LeDuc et al, 1999).

Figure 1 A Gray’s spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris longirostris) in the Gidf of Mexico.

II. Distribution and Ecology

The spinner dolphin is pantropical, occurring in all tropical and most subtropical waters around the world between roughly 30-40°N and 20-30°S (Jefferson et al, 1993). It is typically thought of as a high-seas species, but coastal populations and races/subspecies exist in the eastern Pacific, Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia, and likely elsewhere. In the eastern and western Pacific, the pelagic form has been shown to prey mainly on small mesopelagic fishes and squids, diving to 600 m or deeper (Gilpatrick, 1994; Dolar, 1999), but a dwarf subspecies in inner Southeast Asia, S. I. roseiventris, inhabits shallow waters in the Gulf of Thailand, Timor Sea, and Arafura Sea and consumes mainly ben-thic and reef fishes and invertebrates.

Predators include sharks, probably killer whales (Orcinus orca) and possibly false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens), pygmy killer whales (Feresa attenuata), and short-finned pilot whales (Globiceplwla macrorhynchus). Parasites may cause direct or indirect mortality.

Figure 2 The Central American spinner (Stenella longirostris centroamericana) lacks a bold pattern and has an extremely long beak.

Figure 3 Skull of Stenella longirostris longirostris adult male from Florida.

III. Behavior and Life History

Why the spinner spins is unknown. One animal may spin as many as 14 times in quick succession. It has been suggested that the large underwater bubble plume created by the violent spin and reentry may serve as an echolocation target for communication across a widely dispersed school (Norris et al., 1994). It is also probable that spinning is an outgrowth of an alert state and as such has a social facilitation function. It could also—at least at times—represent play.

School size varies greatly, from just a few dolphins to a thousand or more. Spinner dolphins commonly school together with pantropical spotted dolphins, S. attenuata, and dolphins and small toothed whales of other species. Social organization in Hawaiian waters is fluid, with schools composed of more or less temporary associations of family units; the associations may vary over days or weeks (Norris et al, 1994). Mating appears to be promiscuous. Adult males form coalitions of up to about a dozen individuals; the function of these is unknown. Maximum recorded movements of individuals are 113 km (over 1220 days) in Hawaii and 275 nmi (over 395 hr) in the eastern Pacific.

Gestation is about 10 months. Average length at birth is about 75-80 cm. Length of nursing is 1 to 2 years. Calving interval is about 3 years. Females attain sexual maturity at 4-7 years and males at 7-10 years. Ovulation may be spontaneous. Breeding is seasonal, more sharply so in some regions than in others.

IV. Interactions with Humans

Spinner dolphins have been kept in captivity only in Hawaii, where some have lived for several years. Large numbers have been killed incidentally since the early 1960s by tuna purse seiners in the eastern tropical Pacific; the population of S. I orientalis is estimated to have been reduced to less than one-third of its original size. Likely unsustainably high bycatches also occur in drift nets and purse seines in the Philippines (Dolar, 1994, 1999). As is the case for other small cetaceans caught in fishing nets, local human consumption of by-caught animals in several regions has led to the development of markets and large directed catches from unassessed populations,boding ill for conservation of the species in these regions.