Sea lions, like the fur seals, are members of the family Otariidae. There are presently seven sea lion species in five genera, with one genus exclusive to the Northern Hemisphere (Steller sea lion, Eumetopias jubatus). one that occurs in both hemispheres [in the north, the California (Zalo-phus californiantis) and Japanese (Z. japonicus) sea lions, and in the south, the Galapagos sea lion, (Z. woUebaeki)}, and three that are solely in the Southern Hemisphere (southern sea lion. Otaria flavescens; Australian sea lion. Neophoca cinerea; New Zealand sea lion. Phocartos hookeri).

I. Origins, Classification, and Size

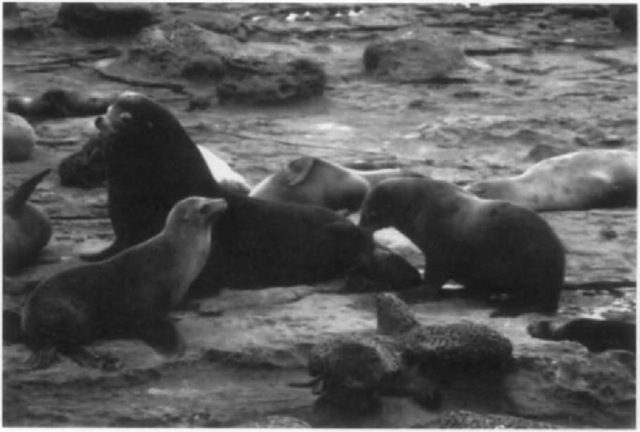

Sea lions originated in the North Pacific region, sharing a common ancestor with fur seals. Although the fossil record for sea lions is poor, it appears they crossed into the Southern Hemisphere about three million years ago. Generally the sea lions have been thought of as a separate subfamily (Otariinae) within the family Otariidae. However, as more genetic analyses are done, this view is being questioned. For example, in one analysis die northern fur seal appears to be more closely related to the sea lions than to the other fur seals, which are all in the genus Arctocephalus. In another analysis, two sea lion species clustered with three Arctocephalus species to the exclusion of the northern fur seal. The only substantial diagnostic morphological distinction between sea lions and fur seals is the presence of an underhair in fur seals but not in sea lions. Sea lions do tend to be larger than fur seals, with both groups exhibiting substantial differences in body mass, and smaller differences in body length, between males and females, a phenomenon known as sexual dimorphism (Fig. 1). Male sea lions are between two and four times heavier than females and up to one and a half times the length. The body mass of males in the different sea lion species ranges from about 250 to 1000 kg and in females from about 75 to 325 kg. In contrast, the heaviest fur seal male is about 300 kg and the heaviest female is about 75 kg. Lengths of male and female sea lions range from 205 to 330 and 180 to 270 cm, respectively.

II. Morphology and Physiology

Sea lions, like fur seals and walruses, differ anatomically from the true seals (phocids) in several ways. Probably most notably is their ability to walk or run rather than crawl on land. Underlying this capability is the ability to rotate the pelvis to a position that allows bringing the hind flippers under the body. As a result, sea lions have more efficient terrestrial locomotion than phocids. Another obvious anatomical feature of sea lions is the extended and flattened fore flippers. Again, this is a feature they have in common witii their otariid fur seal cousins, although the walrus and phocids have relatively short fore flippers. These differences reflect the different swimming modes of these two groups of seals. The sea lions and fur seals use fore flippers to provide thrusting power and the walrus and phocids use their rear flippers.

Consistent with being shallow divers, sea lions have a relatively small lung capacity compared to many other marine mammals. They also have lower oxygen stores (40 ml Oz/kg) than true seals (60 ml 02/kg), which are generally deep divers, but still much higher stores than humans (20 ml 02/kg), for example. Additionally, the relative distribution of oxygen stores is different for sea lions. Sea lions have about 47% of their oxygen in blood, 35% in muscle, and 19% in their lungs. Phocids, however, have 64% of their oxygen in blood. 31% in muscle, and only 5% in their lungs. This larger percentage of oxygen in the lungs of sea lions correlates with the smaller degree to which the lungs collapse from water pressure. In humans. 51% of the oxygen is stored in the lungs.

III. Life History and Reproduction

Sea lions follow a life style typical of that of all the otariids, with some characteristics common to all seals. They are long-lived (probably 15-20 years), have delayed sexual maturation, and have physical and social sexual bimaturation with males maturing more slowly than females. For the three sea lion species adequately studied, females normally give birth for the first time at 4-5 years of age. For six of the seven sea lion species there is an annual breeding cycle, but one species, the Australian sea lion, has a unique cycle of just under 18 months. The net result of this cycle is that there is a gradual shift in the time of year and season when the breeding period occurs. For example, over a 19-year period, between 1973 and 1991, the median date of pupping occurred in every month of the year. No other species of seal exhibits such a pattern. Why this pattern exists is unclear, but it does link to a lactation length of about 17 months in this species.

Figure 1 A male and several female California sea lions illustrating the size differences between males and females (sexual dimorphism). The male is the largest individual. Note the female on the right that is carning a newborn pup using her teeth.

The reproductive behavior of female sea lions follows the typical maternal foraging cycle seen in all other otariids. Females give birth at traditional sites, usually on sandy beaches. Almost without exception a single pup is born to each female. During what has been termed a perinatal period, the female remains with her pup continuously, nursing it frequently. This period ranges from about 7 to 10 days. At the end of the perinatal period, females will have depleted stores of body fat because they have been fasting and begin to make foraging trips to sea, leaving their pups behind on the beach. In some species, most females will come into estrus before they begin foraging trips, whereas in others, estrus will occur after foraging trips have begun. The duration of foraging trips is variable both within and between species (ranging from about 0.5 to 3 days), although they tend to be shorter among the sea lions than among the fur seals (1-12 days). Between foraging trips, females return to their pups on land, nursing them over a period of 0.5 to 1.5 days. This cycle is continued throughout lactation, which lasts about a year for all sea lions, except the Australian sea lion mentioned earlier, which has a 17-month lactation.

A physiological component of this maternal strategy of sea lions is relatively high-fat milk, which provides the energy needed by the pups as they try to grow during the “feast and famine” situation produced by maternal foraging. We do not have measures of milk fat for all sea lion species, but for those that have been studied the fat content of maternal milk ranges from about 15 to 45%. and most likely the level ol fat in a milk relates to the typical length of foraging trips. The best example of this is seen in Zalophus spp. The California species, which has maternal foraging trips of about 2.5 days, produces milk with 43% fat, whereas the Galapagos species, which forages for about a half day before returning to pups, has milk containing only 21% fat. Interestingly, the daily growth rates of sea lion pups, after taking the body size of adults into account, are very similar, suggesting that the maternal strategies are finely tuned to ecological conditions.

The reproductive behavior of male sea lions has been investigated unevenly among the various species. We know almost nothing about the New Zealand and Japanese sea lions but a considerable amount about the California, Galapagos, Steller and southern sea lions. Because females gather on land to give birth and care for their young and estrus is temporally linked to parturition, the conditions are ideal for strong sexual selection through male-male competition. In brief, the tendency for female sea lions to be highly clustered, indeed lying in contact with one another, provides the potential for males to compete for and maintain control over multiple females. The ability to control and mate with multiple females in a given reproductive period is known as polygyny.

As is typical of virtually all otariids. male sea lions return to traditional breeding grounds and vie for positions in areas where females have previously given birth or spent time cooling off during the hottest part of the day. In some species or populations. males may actually defend sites or territories, whereas in others they may be more flexible, defending females directly. Factors that are most important in determining which behavior is typical at a colony are the extent to which females move before they become receptive and the level of competition that exists among males. Female movement is most often associated with the need to cool off because of high ambient temperature. One species for which all studies have shown males only to defend territories is the Steller sea lion. This is likely a result of the high latitude at which this species breeds and the fact that females exhibit little, if any, thermoregulatory movement.

In contrast, the southern sea lion has been shown to behave variably depending on the breeding habitat. At sites where there tend to be large numbers of tidal pools, around which females cluster, males defend territories. However, where there are long narrow sand or pebble beaches, females shift up and down the beach with changes in the state of the tide and air temperatures. Under these conditions, males do not defend territories but shift as females do and defend the females directly.

The level of reproductive success, or number of females mated by the most successful males, may be similar regardless of which pattern of behavior is typical. What seems to constrain the maximum success is the degree to which females are clustered in space and time. If receptive females are too dispersed in time, an individual male may not have enough energy stores to remain competitive throughout the entire season. As food sources are usually not close to the breeding grounds, males must fast during the breeding season; rarely are individual males seen leaving their positions on land. This is true even during the hot part of the day. Minimum estimates of the maximum mating success for the most successful male among the sea lion species are highly variable. The estimate for the most successful Australian sea lion male, a species in which females tend to be quite dispersed, is 7 females mated compared to between 30 and 50 females for California and New Zealand sea lions, species in which females are much more clustered.

This intense competition among males is what produces the extreme sexual dimorphism we see in sea lions and many other seals. At this point it is unclear as to whether the large size of male sea lions is most important in direct competition, i.e., fights and threats with one another, or in the ability to remain ashore for longer periods of time because larger males can store more body fat. In some energetic studies of phocid seals, evidence suggests that it is the amount of energy stores that is more important.

IV. Feeding Habits

Our understanding of sea lion foraging ecology is much poorer than that of fur seals. Diet studies based mainly on analysis of food remains in scats (i.e., feces) do provide a picture of the feeding habits of sea lions, although this is with some bias. In all seven species, evidence suggests that they are primarily fish eaters and secondarily eat cephalopods (e.g., squid and octopus). The southern sea lion and the Australian sea lion, which live in proximity to penguin populations, have been found to prey on penguins occasionally. Penguin predation has not been reported in Galapagos sea lions, however, despite being sympatric with the Galapagos penguin. The two larger sea lions, Steller and southern, also prey periodically on northern and South American fur seal pups, respectively.

V. Population Status

The status of sea lion populations is variable. Two species, the California sea lion and the southern sea lion, are not currently listed as being in trouble. The Japanese sea lion has not been sighted since the 1970s and is now considered extinct.

The World Conservation Union (IUCN) considers the Galapagos sea lion vulnerable because there has been no reliable population estimate since the 1970s, at which time the Galapagos sea lion was thought to number about 30,000. California sea lions are probably in excess of 300,000, and southern sea lion populations probably exceed 200,000. What is not clear is how many southern sea lions in Peru died during the severe El Nino of 1997/1998. The sea lion species for which there is greatest concern at present is the Steller sea lion. Although it is not the smallest population by far (estimated at about 96,000), it has declined by about 80% since the 1970s. It is currently considered endangered by the IUCN and as endangered in the western and threatened in the eastern U.S. stock under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. While the precise cause of the decline is unclear, there is some evidence to implicate a decline in food supply, perhaps resulting from a mixture of commercial fishing and environmental changes known as climatic regime shifts. The Australian and New Zealand sea lions are known for their small populations historically and are at less than 15,000 animals each. The Australian species, which has been classed as rare, has been removed from the IUCN list because the population has been increasing and now appears to have leveled off. The New Zealand species remains listed as threatened, having undergone a major die-off in 1998, with 53% of the pups and perhaps as manv as 20% of the adults perishing.