Scrimshaw is an occupational handicraft of mariners employing by-products of the whale fishery, often in combi-_ nation with other found materials. Indigenous to the whaling industry, where it was typically a pursuit of leisure time at sea, it was also adopted in other trades and was occasionally practiced ashore. It arose among Pacific Ocean whalers circa 1817-1824, persisted throughout the classic “hand-whaling” era of sailing-ship days into the 20th century, and persisted in degraded form among “modern” whalers on factory ships and shore stations until the industry shut down in die third quarter of the 20th century. Since the early 20th century, similar materials and techniques have simultaneously been employed by nonmariner artisans for both commercial and hobbyist purposes.

There is no consensus regarding etymology. Plausible and eccentric dieories alike have been advanced without any creditable evidentiary basis, whereas academic lexicography (notoriously inconclusive respecting nautical terms) fails to present any convincing hypothesis. The term—also rendered skrimshank, skimshander, skirmshander, and skrimshonting— first appeared in American shipboard usage circa 1826, when the recreational practice of scrimshaw was less than a decade progressed. It originally referred not to whalers’ private diversions, but to the fairly common practice whereby crewmen were required to make articles for ship’s work (such as tools, tool handles, thole pins, belaying pins, and tackle falls). Sperm whale bone is ideally suited to such uses: on any “greasy luck” voyage it was in plentiful supply at no cost, its workability is equivalent to the best cabinetmaking hardwoods, its tensile strength is greater than oak, and for many applications its self-lubricating properties were highly desirable. Such was analogously the case regarding the adaptability of cetacean bone and ivory to whales’ recreational handicrafts, to which the term scrimshaw (and its many variants) came to refer by the 1830s.

I. Materials and Species

Materials associated most commonly with scrimshaw are the ivory teeth and skeletal bone of the sperm whale, the ivory tusks of the walrus, and the baleen of various mysticete species (the toothless, baleen-bearing whales). In the 19th century the principal prey species were, roughly in descending order of importance, sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), right whales (Eubalaena spp.), Arctic bowhead (Balaena mysticetus), gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus), and humpback (Megaptera no-vaeangliae). These and the long-finned pilot whale or so-called “blackfish” (Globicephala melas), which was hunted primarily from shore, were taken primarily for oil, the mysticetes secondarily for baleen. [The fast-swimming blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and finback (B. physalus) could not be hunted effectively prior to the introduction of steam propulsion and heavy-caliber harpoon cannons in the late 19th century.] From the late 16th century, by reason of geographical proximity of Arctic habitats and similar uses of their meat and oil, the hunt for walruses (Odobenus rosmarus) was intimately conjoined with commercial whaling. Later, even when whalers were no longer taking walruses themselves, they characteristically obtained walrus tusks through barter with indigenous Northern peoples.

Commercial uses of walrus ivory were few; there was no significant commercial application for cetacean skeletal bone until the 20th century (when it was ground and desiccated into industrial-grade meal and fertilizer); the utility and market value of baleen (“whalebone”) were subject to mercurial fluctuations of fashion; and sperm whale teeth had little or no commodity value. They thus became available for whalers’ recreational use, as did teeth of the Antarctic elephant seal (Mirounga leonina), the lower mandibles of various dolphins and porpoises, and tusks of the elusive narwhal (Monodon monoceros). (Narwhal ivory proved too difficult and brittle for anything much beyond canes and analogous shafts, such as hatracks or bedposts.)

The characteristic pigment for highlighting engraved scrimshaw was lampblack, which is essentially a viscous suspension of carbon particles in oil. (The notion that sailors used tobacco juice for this is a colorful fabrication with no basis in fact.) Lampblack, collected easily from lamps, stoves, and tryworks (shipboard oil-rendering apparatus), was in abundant supply on a whale ship. Colors were introduced almost at the outset: Edward Burdett was using sealing wax and other pigments by 1827 (Fig. 1); full polychrome scrimshaw debuted within the next decade. Sealing wax had the advantages of being universally available, relatively inexpensive, brilliantly colored, and color-fast. Applied properly, it has proven resilient and tenacious, the color as vivid today as when the scrimshaw was new. Improper application—if the cuts are too smooth or insufficiently contoured to grab and hold the wax—results in significant losses from handling and natural desiccation. Sealing wax had the disadvantage of offering only a limited spectrum of colors, all strong. Ambient pigments, however, could be mixed and blended, affording greater subtlety. From the characteristic leeching of pigment into the substrata of some polychrome scrimshaw, a phenomenon that occurs with water- and alcohol-soluble colors but not with waxes or heavy oil-based pigments, it is clear that ambient colors were also favored. Store-bought inks, homemade dyes extracted from berries, and greens from common verdigris seem to predominate; however, their composition has not been investigated comprehensively.

Inlay and other secondary materials—rare on engraved scrimshaw but often encountered on “built” or “architectonic” scrimshaw—were typically obtained at little or no cost, such as other marine byproducts (tortoise shell, mother-of-pearl, sea shells), various woods brought from home or obtained in various ports of call (including exotic tropical species from Africa and Polynesia), and miscellaneous bits of metal (fastenings and finials were often crafted from silver- or copper-alloy coins, typically coins minted in Mexico and South America).

II. Scrimshaw Precursors

Medieval European artistic productions in walrus ivory and cetacean bone were many, but the whalers themselves had no part in them beyond gathering the raw materials. Cetacean bone panels and stilettos survive from the Viking era, some incised with rope patterns and animal figures, and cetacean bones served as beams in vernacular buildings in Norway and the Friesian Islands, but even these do not appear to have been made by whalers and are not known to have been part of their occupational culture. Monastic artisans in Denmark and East Anglia carved walrus ivory and cetacean bone into votive art, primarily altar pieces, friezes, and crosses, whereas craftsmen at Cologne and elsewhere produced secular game pieces and chessmen from the same materials. So important was the “Royal Fish” to the Viking economy that a highly sophisticated body of law evolved to regulate whaling itself and the ownership, taxation, distribution, and export of whale products, whether acquired fortuitously (from stranded carcasses) or by hunting. Pliny the Elder (first century C.E.), Olaus Magnus (1555), Conrad von Gessner (1558), and Ambroise Pare (1582) listed the uses of baleen for whips, springs, garment stays, and umbrella ribs; and the emergence of pelagic Arctic whaling in the 17th century encouraged a search for new applications, especially in Holland. The search, however, proved fruitless and was abandoned by circa 1630, occasioning the appearance of sailor-made baleen objects: there was simply no longer any reason to restrain whalers from using baleen for their private diversions (two centuries later the same principle would make sperm whale teeth available for scrimshaw).

Ditty boxes were the first manifestation of whalers’ work. Typically, these have polished baleen sides bent to the oval shape of a wooden bottom 30-35 cm long, to which the baleen is fastened with copper nails and fitted with a wooden top. Two made in 1631 by an anonymous Rotterdam whaling commandeur have baleen sides incised with portraits of whaleships, the wooden tops relief carved with the Dutch lion rampant surrounded by nautical symbols, human figures, and decorative borders. A few North Friesian whaleman-artists of the next generation are known by name. Jacob Floer of Amrum engraved buildings, trees, and geometrical borders on the baleen sides of an oval box, signed and dated 1661. Peter Lorenzen of Sylt signed and dated another in 1687. The form continued for the duration of Arctic whaling and was perpetuated with myriad variations by American and British scrimshaw artists in the 19th century.

Figure 1 Panbone plaque bi Edward Burdett (1805-1833) of Nantucket, circa 1828. The earliest known scrimshaw artist, Burdett was active from 1824 until he was killed by a whale in 1833. His work is characterized by a bold, confident style, with deep blacks and red sealing-wax highlights. He was serving as a mate in the William Tell when he engraved this section of sperm whale bone, inscribed “William Tell, of New York, homeward bound, in the latitude of. 50 13. S. long[itude] 80. W. got shipwrecked”; “lost her rudder 6- c.”; “by. E. Burdett.” 15.7 X 31.8 cm.

Another early form was the mangle (paddle for folding cloth). An Amsterdam whaling commandeur decorated one with carved geometric ornaments, signed, dated, and inscribed, “Cornelis Floerensen Bettelem. Niet sonder Godt [Not without God]. Anno 1641.” A century later a North Friesian whaling master, L0dde Rachtsen of Hooge, made one for his daughters dowry: it has a pierced-work handle and caned geometric and floral decorations, the broadside portrait of a spouting bowhead whale, and a carved inscription dated 1745. Respecting technical aspects of execution and the iconography of their decoration, this kind of piece is the direct ancestor of the sperm whalemen’s decorated baleen corset-busks of the 19th century.

III. Origins and Practice

Pictorial engraving on sperm whale teeth—the quintessential manifestation of scrimshaw—resulted from changing circumstances in the fishery in the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars (of which the American theater was the so-called War of 1812). It arose collectively among British and American whalers in the 1820s in the Hawaiian Islands, where (beginning in 1819) the fleets customarily laid over for weeks on end between seasonal cruises, providing ample opportunities for fraternization and foment.

In the late 17th century, British colonists on the Atlantic seacoast of New York and Massachusetts hunted right whales along shore—an ancillary day fishery, prosecuted by fishers and farmers in rowboats launched from sandy beaches. In the 18th century, expanding markets occasioned offshore cruises in small sailing vessels. The discovery of sperm whales in proximity to New England is ascribed by tradition to Captain Christopher Hussey of Nantucket when he was blown off course while right whaling in 1712. The colonists tuned their technology to accommodate sperm whaling, pioneered the refining of sperm whale oil and the manufacture of spermaceti candles (America’s first industry), and developed thriving export networks. Whaling evolved into a full-time occupation, and a distinctive caste of whaler-mariners emerged with its own occupational culture. Scrimshaw would become an integral component of this culture, but it took a whole century for the right circumstances to gel.

Colonial whaling cruises were seasonal, following the Atlantic trade winds on comparatively short passages to and from the grounds. Only a few whales were required to fill the hold before heading home, usually after only a few weeks. The opening of the Pacific grounds in the 1790s changed shipboard dynamics dramatically. Voyages necessarily became longer, as much as 3 or 4 years by the 1840s. The larger catch required to make long voyages profitable mandated larger vessels with larger crews so that three to five whaleboats could be launched for the hunt. The effective result was overmanning and an unprecedented abundance of shipboard leisure—long outward and homeward passages, and idle weeks, even months between whales, when there was little to do but maintain the ship and wait. Most sailors worked “watch-on-watch” in 4-hr shifts, day and night, whenever the ship was underway, but whaleship crews had most nights off: the hunt could not be prosecuted effectively in darkness, and cutting in (flensing) a carcass with sharp blubber spades was dangerous enough even in daylight. Apart from rendering blubber already on hand, there was little work to do evenings. More than in any other seafaring trade, 19th-century whalers had time to spare. They filled it with reading, journal-keeping, drawing, singing, dancing, gamming (visiting among ships at sea), and a host of other diversions.

At the critical juncture, just when things were ripe for scrimshaw, teeth were in short supply. For in the meanwhile, the China Trade, pioneered in the 1780s, had established a network of Far East destinations and products that involved barter with Pacific islanders to obtain goods for Canton. China traders soon realized that many island cultures placed great value on whale teeth, from which they crafted various totemic and decorative objects. Teeth could be obtained cheaply from whalers (there being no other market), so the China merchants bought them up for barter in the Pacific. Such scrimshaw as there was in the 18th century was therefore limited primarily to implements made of skeletal bone—straightedges, hand tools, a few early swifts (yarn-winders), and corset busks; oi these, comparatively few were made prior to the florescence of scrimshaw commencing in the 1820s.

Captain David Porter of the U.S. Naval frigate Essex was the inadvertent catalyst for the emergence of scrimshaw. Porter’s wartime purpose had been to inflict depredations on British shipping and to disrupt British whaling in the Pacific. His narrative (published in 1815, reissued in an expanded edition in 1821) was valued by mariners for its explicit accounts of conditions in the Marquesas and Galapagos Islands and on the coast of Chile and Peru. It also incidentally revealed the barter value of whales teeth in Polynesia and disclosed particulars of how they could be gathered cheaply—this at just around the time the vanguard of the whaling fleet reached Hawaii (1819). There was soon a surplus of whales teeth on the Pacific market; as the teeth were no longer valuable as a commodity, they could be relegated to sailors for private use.

Accordingly, the earliest authentic date on any pictorial sperm whale scrimshaw is 1817—a tooth commemorating a whale taken by the ship Adam of London off the Galapagos Islands (Fig. 2); and the earliest provisionally identifiable whaleman-engraver of sperm whale ivoiy is J. S. King, whaling master of London and Liverpool, to whom two teeth are attributed, one perhaps as early as 1821. These suggest a possible British genesis of pictorial scrimshaw; however, the earliest definitively attributable work is by an American, Edward Burdett of Nantucket, who first went whaling from his native port in 1821 and was scrimshandering by 1824. Fellow Nantucketer Frederick Myrick was the first to sign and date his scrimshaw—three dozen teeth produced during 1828-1829 as a seaman aboard the Nantucket ship Susan. Two teeth by Burdett and two “Susan’s Teeth” by Myrick were accessioned by the East India Marine Society of Salem, Massachusetts, prior to 1831, while both artists were still living—the first scrimshaw to enter a museum collection. That Myrick’s work was listed generically as “Tooth of a Sperm Whale, curiously carved” and “Another, carved bv the same hand,” with no mention of the exquisitely engraved pictures on them, nor of the artist’s name (both are signed), nor of the term scrimshaw, testifies to the newness of the genre, perhaps also to the low esteem in which sailors’ hobby work was held by the great merchants of Salem at the time.

Figure 2 Genesis of scrimshaw, circa 1817. The oversize tooth is inscribed, “This is the tooth of a sperm whale that was caught near the Galapagos Islands by the crew of the ship Adam [of London], and made 100 barrels of oil in the year 1817.” Produced in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, when the British and American whaling fleets were endeavoring to recover their former prowess in the Pacific, it is believed to be the earliest full-scale work of engraved pictorial scrimshaw. Length 23.5 cm.

In the 1830s scrimshaw became widely generalized. On some whaling vessels virtually the entire ship’s company participated. In his journal of the New Bedford bark Abigail during 1836-1838, Captain William Hathaway Reynard remarked, “The cooper is going ahead making tools for scrimsham. We had a fracas betwixt the cook and the stewart [sic] … All hands employed in scrimsa.” In other ships the best ivory and bone may have been relinquished to some particularly talented member of the crew, such as Joseph Bogart Hersey of Cape Cod on the Provincetown schooner Esquimaux in 1843: “This afternoon we commenced sawing up the large whale’s jaws . . . the bone proved to be pretty good and yielded several canes, fids, and busks. I employed a part of my time in engrav[ing] or flowering two busks. Being slightly skilled in the art of flowering; that is drawing and painting upon bone; steam boats, flower pots, monuments, balloons, landscapes &c &c &c; I have many demands made upon my generosity, and I do not wish to slight any; I of course work for all.”

The whaleship labor force was very young on average, with green hands often in their early teens; common seamen and even seasoned harpooners were rarely over thirty. Among the greatest scrimshaw artists, Frederick Myrick retired from whal ing and from scrimshaw at age 21, Edward Burdett was barely 28 when he was killed by a whale, and Welsh ship’s surgeon W. L. Roderick left the fishery at 29. Nevertheless, although in the minority, older hands contributed mightily. Seaman Silas Davenport may have been in his forties when he constructed a fine swift of bone and ebony. Former whaleman N. S. Finney was still engraving walrus ivory on commission in San Francisco in his sixties. Ship’s carpenters and coopers—trained craftsmen with skills well adapted to scrimshaw, especially architectural pieces—were normally older than the average crewman. So, too, whaling captains, many of whom were devoted scrimshaw artists: Manuel Enos cut brilliant polychrome portraits into whale ivory right up to the time he was lost at sea at age 55; Frederick Howland Smith was scrimshandering from age 14 until he retired at 61; and the grand old man. Captain Ben Cleveland, was still making napkin rings, mantle ornaments, and scrimshaw gadgets in the 1920s, at age eighty.

Scrimshaw was quintessentially a diversion of the whalemen’s ample leisure hours, to fill time, and produce mementos as gifts for loved ones at home. It was occupationally rooted in and wholly indigenous to the deepwater whaling trade, but was eventually also adopted by merchant sailors, navy tars, and occasionally the seafaring wives and children of whaling masters.

Unfortunately, practitioners in whatever trade rarely signed or dated their work, and family provenance has seldom preserved details of the origins of legacy pieces. Thus, scrimshaw has hitherto been mostly anonymous, the names of only a handful of practitioners known. However, systematic forensic studies commencing in the 1980s have made stylistic and icono-graphical attributions increasingly possible, and the names and works of a few hundred individual artists are now documented with varying degrees of specificity.

IV. Taxonomy

Scrimshaw took many forms. Henry Cheever mentions whalers “working up sperm whales’ jaws and teeth and right whale [baleen] into boxes, swifts, reels, canes, whips, folders, stamps, and all sorts of things, according to their ingenuity” (The Whale and His Captors, 1850); and Herman Melville alludes to “lively sketches of whales and whaling-scenes, graven by the fishermen themselves on Sperm Whale-teeth, or ladies’ busks wrought out of the Right Whale-bone, and other like skrimshander articles, as the whalemen call the numerous little ingenious contrivances they elaborately carve out of the rough material in the hours of ocean leisure” (Moby-Dick, 1851). Various tools were used for cutting and polishing, but forensic scrutiny corroborates Melville’s observation that the ordinary knife predominated: “Some of them [the whaleman-artisans] have little boxes of dentistical-looking implements, specially intended for the skrimshandering business. But in general, they toil with their jack-knives alone; and, with that almost omnipotent tool of the sailor, they will turn you out anything you please, in the way of a mariner’s fancy.”

Scrimshaw objects intended for practical use included hand tools, kitchen gadgets, sewing implements, toys, and even full-sized furniture. Some, such as fids, straightedges, tool handles, seam-rubbers, napkin rings, and even some canes, could be carved or turned from a single piece of ivory or bone. Although they had a specific function, corset busks (made of bone, walrus ivory, or baleen) were often elaborately engraved; even apart from being products of painstaking labor, as intimate undergarments they were not bestowed casually. Other implements were constructed from two or more pieces joined or hinged together—pie crimpers with rotating jagging wheels and fold-out forks (Fig. 3); canes with shafts of one material, pummels of another, and inlay of a third. The most elaborate forms were truly “built” and may properly be called architectural or architectonic. Swifts (yarn winders) have numerous moving parts, with metal pinions and ribbon fastenings (Fig. 4). Bird cages, a labor-intensive technical challenge, could run the gamut of Victorian complexity. Sewing boxes, ditty boxes, chests of drawers, lap secretaries, pocketwatch stands, mantle ornaments, and other composite constructions typically employed combinations of wood, ivory, and bone and may have hinged lids, internal compartments, legs, finials, handles, drawers, drawer pulls, inlay, and all manner of ornamentation.

The quintessential form of purely decorative scrimshaw is engraved ivory and bone, usually rendered in a single medium—a tooth or pair of teeth; a tusk or pair; or a plaque, strip, or section of sperm whale panbone (jawbone). Finished teeth were sometimes set into wooden, silver, or coin-silver mounts; plaques might be framed by the artist: engraved strips of baleen could become oval boxes. Alternately, teeth and tusks could be carved into stand-alone sculptural forms, such as human or animal figures, or could become the components of complex ship models.

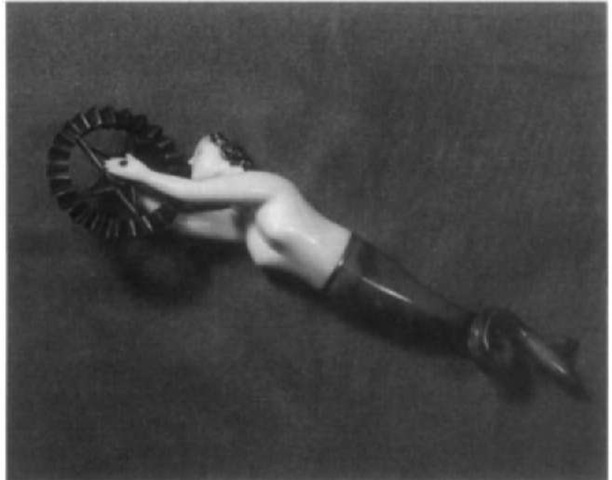

Figure 3 Pie crimper in the form of a mermaid, New Bedford, circa 1875. Practical in origin, these classic kitchen implements inspired some of the scrimshaw’s most creative forms and elaborate ornamentation. The jagging wheel was used for crimping pie crusts; they often also had ivory forks to puncture the top of the crust. This one was made aboard the New Bedford ship Europa, Captain James H. McKenzie, during 1871-1876. Length 18 cm.

Figure 4 Swift of sperm whale ivory and skeletal bone by Captain James M. Clark, circa 1835-1850. Made by a Yankee whaling captain, this exquisite piece typifies the best of the scrimshaw genre. It is inlaid with abalone shell and baleen, fastened with copper, tied with silk ribbons, fitted with two turn-scretvs in the form of clenched fists, and has a silver presentation plaque inscribed “R W Yose from Ja Clark.” Height 40.7 cm. Sivifts were a distinctly American form, used for winding the yarn employed in knitting and occasionally other domestic handicrafts and cottage industries.

There were no rules and few precedents governing the choice of subject matter for pictures on scrimshaw. The earliest work— by the anonymous Adam engraver, J. S. King, Edward Burdett, and Frederick Myrick—was almost exclusively devoted to ship portraiture and whaling scenes. Figures of Columbia, Liberty, and Britannia appeared by around 1830. The ensuing generation enlarged the vocabulary to include patriotic portraiture (notably of Washington and Lafayette), inanimate patriotic devices, female portraiture, landscape, naval engagements, sentimental family scenes, and mortuary motifs (Fig. 5). Gradually, these were canonized as standard genre conventions. Some individual artists developed distinctive styles and themes. George Hilliott’s polychrome teeth dialectically juxtapose a Polynesian wahinee in a grass skirt on one side and a New England lady in a fashionable gown on the other. The anonymous “Banknote engraver” did meticulous portraits with banknote-like borders (hence the pseudonym). The “Eagle Artisan” engraved red-and-black American eagles and bold portraits. The “Lambeth Busk Engraver” made busks with London vignettes: a prime example features Lambeth Palace. Much naval scrimshaw is adorned with patriotic devices and naval engagements. Like whalemen’s scrimshaw, some examples refer to specific vessels and events. A notable British example is credited to HMS Beagle on the same voyage on which Darwin evolved his theorv of natural selection. Edward Yorke McCauley—later an admiral and noted Egyptologist—when he was a young midshipman aboard the U.S. Frigate Powhattan on Perry’s historic Japan expedition in the 1850s. engraved two walrus tusks with portraits of the Powhattan and Susquehanna, exotic Oriental watercraft. and glimpses of Japan, Hong Kong, and Brunei. Even a Confederate infantryman tried his hand: Hampton Wilson, Irish immigrant. North Carolina sharecropper. Confederate draftee, and Union prisoner of war, while recuperating in a military hospital in Kentucky successfully “flowered” a pair of walrus tusks with military and naval vignettes, using materials and methods presumably supplied by a Yankee whaling veteran among his fellow patients.

Figure 5 Family album wall hanging, Netv England, circa 1850. This unusual, elaborate constmction features 12 tintype photographic portraits mounted in a triangular framework of walrus ivory and bone. The polychrome engraving on the walrus tusks is particularly interesting, as the woman-and-child portrait pair on the right is no doubt copied from a magazine fashion plate (in typical whalers’ fashion), whereas the woman-with-telescopc on the left appears to be an original image. Height 50 cm.

Most scrimshaw pictures were inspired by or adapted from illustrations in contemporaneous books and periodicals; copying and even direct tracing were standard scrimshaw conventions. Because of their specific functional objectives, scrimshaw implements and architectonic forms were also mostly derivative. However, some of the best pieces—and many of the worst—were truly original creations, drawn from the maker’s experience or imagination. A few have authentic stature as significant art, whereas others are little more than mere valentines. In the aggregate, anonymity and quality aside, as an indigenous occupational genre scrimshaw comprises some of the most characteristic and revealing documents of any occupational group, capable of providing profound insights into the life, work, and intentionality of the mariners who made them.

V. Museum Collections

Hull Maritime Museum. Kingston on Hull, England. Municipal museum in England’s most historic Arctic whaling port; the most significant scrimshaw collection outside the United States.

Kendall Whaling Museum, Sharon, Massachusetts. World’s largest and most comprehensive scrimshaw collection; world’s only Scrimshaw Forensies Laboratory; annual Scrimshaw Collectors’ Weekend; many scrimshaw publications.

Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, Connecticut. Comprehensive collection includes important loan deposits from other private and institutional collections; notable for substantive exhibition and informative catalogue.

Nantucket Whaling Museum (Nantucket Historical Association), Nantucket, Massachusetts. Eminent collection in the birthplace of sperm whaling and hometown of scrimshaw pioneers Edward Burdett and Frederick Myrick.

New Bedford Whaling Museum (Old Dartmouth Historical Society), New Bedford, Massachusetts. Large museum; extensive scrimshaw collection in the world’s greatest whaling port.

Peabody Essex Museum of Salem, Massachusetts. Outstanding collection, brilliantly exhibited; museum founded 1799 as East India Marine Society; world’s oldest collection of scrimshaw (1831).

In addition, there are modest but worthwhile collections at the Christensen Whaling Museum (Sandefjord. Norway), the Providence (Rhode Island) Public Library, the Scott Polar Research Insitute (University of Cambridge, England), South Street Seaport Museum (New York City), Whaler’s Village (La-haina, Maui, Hawaii), the Whaling Museum at Cold Spring Harbor (New York), and several state and municipal museums and libraries in Australia (Sydney; Melbourne; Hobart; and Launceston, Tasmania).

![Panbone plaque bi Edward Burdett (1805-1833) of Nantucket, circa 1828. The earliest known scrimshaw artist, Burdett was active from 1824 until he was killed by a whale in 1833. His work is characterized by a bold, confident style, with deep blacks and red sealing-wax highlights. He was serving as a mate in the William Tell when he engraved this section of sperm whale bone, inscribed "William Tell, of New York, homeward bound, in the latitude of. 50 13. S. long[itude] 80. W. got shipwrecked"; "lost her rudder 6- c."; "by. E. Burdett." 15.7 X 31.8 cm. Panbone plaque bi Edward Burdett (1805-1833) of Nantucket, circa 1828. The earliest known scrimshaw artist, Burdett was active from 1824 until he was killed by a whale in 1833. His work is characterized by a bold, confident style, with deep blacks and red sealing-wax highlights. He was serving as a mate in the William Tell when he engraved this section of sperm whale bone, inscribed "William Tell, of New York, homeward bound, in the latitude of. 50 13. S. long[itude] 80. W. got shipwrecked"; "lost her rudder 6- c."; "by. E. Burdett." 15.7 X 31.8 cm.](http://lh6.ggpht.com/_NNjxeW9ewEc/TNGjsEdMyBI/AAAAAAAAPlg/6KIrXPZRP9E/tmp1DF65_thumb_thumb1.jpg?imgmax=800)

![Genesis of scrimshaw, circa 1817. The oversize tooth is inscribed, "This is the tooth of a sperm whale that was caught near the Galapagos Islands by the crew of the ship Adam [of London], and made 100 barrels of oil in the year 1817." Produced in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, when the British and American whaling fleets were endeavoring to recover their former prowess in the Pacific, it is believed to be the earliest full-scale work of engraved pictorial scrimshaw. Length 23.5 cm. Genesis of scrimshaw, circa 1817. The oversize tooth is inscribed, "This is the tooth of a sperm whale that was caught near the Galapagos Islands by the crew of the ship Adam [of London], and made 100 barrels of oil in the year 1817." Produced in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, when the British and American whaling fleets were endeavoring to recover their former prowess in the Pacific, it is believed to be the earliest full-scale work of engraved pictorial scrimshaw. Length 23.5 cm.](http://lh6.ggpht.com/_NNjxeW9ewEc/TNGj1kc-DbI/AAAAAAAAPlo/wEmpbJoWy0s/tmp1DF66_thumb_thumb1.jpg?imgmax=800)