Most people are surprised to learn that some species of dolphins, and one porpoise species, live either entirely or partly in freshwater rivers and lakes. These animals are obviously exceptional, and they are the result of geologic processes that allowed (or forced) marine-adapted species to become established in inland waters. River dolphins exhibit some extreme characteristics in their morphology and sensory systems. They are also among the most seriously threatened cetaceans because their habitat and resources must be shared with many millions of people.

I. Definition and Distribution

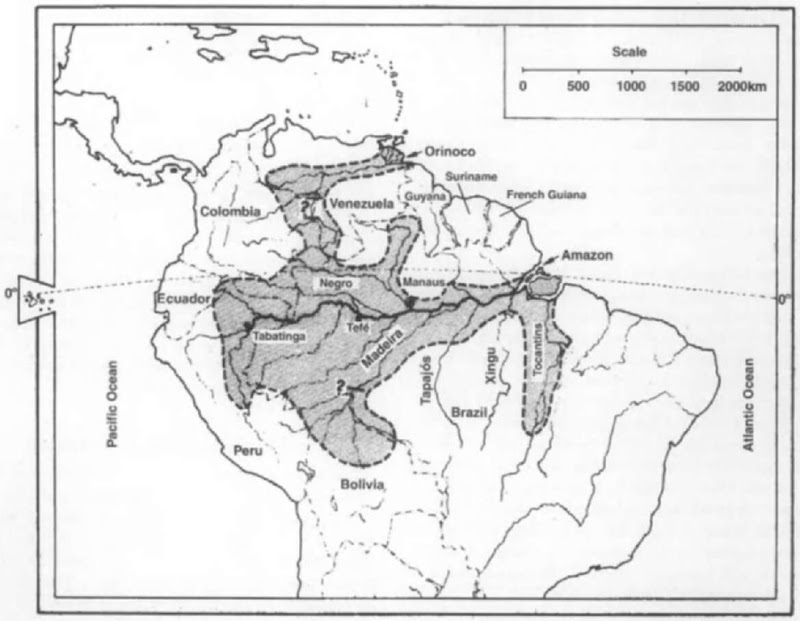

The term “river dolphin” is not unambiguous. In Rice’s (1998) evaluation of marine mammal systematics, for example, he assigned the term to the “peculiar long-snouted” dolphins in four single-species genera: Platanista (the Indian river dolphin), Lipotes (the Chinese or Yangtze river dolphin), Inia (the Amazon river dolphin), and Pontoporia (the La Plata dolphin). He also contends that each of these genera belongs to a separate family and that Platanista is the only living representative of the primitive superfamily Platanistoidea. The previous convention had been to consider the four morphologically similar species, or species groups, as all falling within the Platanistoidea. Although the genera Lipotes and Pontoporia are clearly monospecific, it has been customary to recognize two species of Platanista—the Indus dolphin (P. minor) and the Ganges dolphin (P. gangetica). Rice (1998) found no solid morphological evidence to distinguish them and thus proposed that they be considered subspecies: P. gangetica minor and P. g. gangetica. There is no question that the two populations have been totally isolated for a considerable time (at least hundreds of years). P. g. minor is confined to the Indus drainage in Pakistan, whereas P. g. gangetica occurs in the Ganges, Brahmaputra, Megna, Kar-naphuli, and Sangu drainage systems of India, Bangladesh, and Nepal. There are three separate populations of the boto (Inia geoffrensis): the Bolivian subspecies I. geoffrensis boliviensis in the Madeira River drainage above the Teotonio Rapids at Porto Velho, the Amazonian subspecies I. g. geoffrensis distributed throughout the Amazon drainage basin except the upper Madeira system, and the Orinoco subspecies I. g. humboldtiana distributed throughout the Orinoco drainage basin (Fig. 1). The Yangtze River dolphin or baiji (Lipotes vexiJlifer) is endemic to China’s Yangtze River system. In the past, it also occurred at least seasonally in the two large lakes, Dongting and Poyang, appended to the middle reaches of the Yangtze.

However tortuous the arguments may be with regard to the number of species or subspecies, and their systematic relationships, a more immediately practical way to define “river dolphins” is according to their present-day distribution and ecological position in nature. If river dolphins are defined only as those cetaceans that live solely or primarily in rivers, then die La Plata dolphin or franciscana (Pontoporia blainvillei) must be excluded because it lives in coastal marine waters of eastern South America, including the estuary of the Rio de la Plata (River Plate) between Argentina and Uruguay. At the same time, several species can be added to the list. The tucuxi (Sotalia fluviatilis) inhabits tropical coastal marine waters of eastern South and Central America but also lives far up die Amazon to the Andean foothills, frequently entering lakes and side channels as well as being abundant in the large, fast-flowing main rivers. The species also occurs in the lower Orinoco River and in the lower reaches of rivers in Guyana and Surinam. Rice (1998) recognizes two subspecies: die freshwater S. f. fluviatilis and the marine S. f guianensis. The Ir-rawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) similarly occurs in nearshore marine and estuarine waters of Southeast Asia, portions of Indonesia, and northern Australia, but it is also present far up several large rivers, including die Irrawaddy, Mekong, and Mahakam. With further study, there will almost certainly be grounds for recognizing subspecies and geographically separate populations of Orcaella. The finless porpoise (Neophocaena pho-caenoides) also fits the category of a facultative freshwater cetacean. Although it occurs primarily in shallow marine and deltaic waters from the northern Arabian Sea, coastwise, to Japan, one population inhabits the Yangtze River and its adjoining lake systems to as far as 1670 km upriver from Shanghai. This population is classified as a separate subspecies (N. p. asiaeorientalis). Finless porpoises also have been known to occur at least several tens of kilometers up the Indus and Yalu rivers.

Figure 1 Distribution of the boto, shotting three main river systems inhabited. Upper “?” indicates likely barrier between Orinoco and Amazon subspecies; lower “?” indicates likely banier between Amazon and Bolivian subspecies.

Regardless of how one defines them, the modern river cetaceans occur in only two continents: South America and Asia. Most questions regarding their origins and how they evolved remain unresolved. In the case of Inia, for example, one hypothesis is that their ancestors entered the Amazon basin from the Pacific Ocean approximately 15 million years ago, while another is that they entered from the Atlantic Ocean only 1.8-5 million years ago.

II. Behavior and Ecology

Little, in fact almost nothing, is known about river dolphin societies: how they are structured, how individuals coalesce and disperse to form associations, or whether bonds between individuals are long-lasting or transient. In general, these animals seem not to be highly social, with observed group sizes rarely exceeding 10 or 15 individuals. Yet the densities at which diey exist, expressed in terms of individuals per unit area of water surface, sometimes far exceed those of marine cetaceans. For example, botos and tucuxis in portions of die upper Amazon system typically occur in densities of 1 to 10 individuals/km2 (Vidal et al, 1997).

Figure 2 Despite the impression in this photo from Marineland of Florida that botos are sociable, a major problem with captive groups has been the extremely aggressive behavior of mature males.

The distribution of river cetaceans is far from random. They tend to congregate at particular points in a river, especially at confluences (where rivers or streams converge), sharp bends, and sandbanks, and near the downstream ends of islands. In a detailed study of the distribution of Ganges dolphins in Nepal’s Karnali River, Smith (1993) found the animals primarily in eddy countercurrent systems of the main river channel. Such areas of interrupted flow occur when fine sand or silt is deposited as a result of stream convergence. It is not entirely clear why the dolphins are attracted to these sites, but it likely has some relation to prey availability and energy saving. As Smith (1993) points out, positions within eddies “require minimal energy to maintain but are near high-velocity currents where the dolphins can take advantage of passing fish.” Large confluences may contain tens of dolphins at a given time, but such concentrations appear to be adventitious rather than formed for social reasons. In other words, noninteracting individuals are found in close proximity due to die clumped nature of resources and refugia in the river systems where they are found. There are, of course, differences in degrees of sociability among the species. The author has seen as many as 12-15 tucuxis actively herding prey fish against a riverbank in concert, whereas botos appear to be solitary hunters most of the time, even when they are chasing the same school of fish. This applies equally to Indus and Ganges dolphins, which always seem to be acting individually or in very small groups.

In addition to their freshwater habitat, river dolphins have a number of characteristics that set them apart from other cetaceans. The eyes of Indus and Ganges dolphins lack a crystalline lens, rendering the animals functionally blind. At most, they may be able to perceive gross differences between light and dark. Because most of their habitat is highly turbid, underwater vision would be of little use. These dolphins usually swim on their side, with one flipper (most often the right one) trailing near the river bottom and the body oriented so that the tail end is somewhat higher in the water column than the head end. Their head nods constantly as they scan acoustically for prey and obstacles, Indus and Ganges dolphins remain active day and night. All river dolphins are endowed with a sophisticated biosonar system, but those other than the Indus and Ganges dolphins also have good vision.

All river dolphins have adapted to living in a highly dynamic environment. Although much of their habitat is silty, they also occur in areas where the water is clear, as in the upper reaches of the Ganges, or “black” (stained by tannic acid), as in many Amazon and Orinoco tributaries. Water levels in the lower Amazon can vary seasonally by as much as 10-12 m. During the dry season, the dolphins (and other fauna) are restricted to the deep channels of lakes and rivers, while during the flood season they can range widely. Amazon dolphins penetrate into rain forests and venture onto grasslands during the floods. Their diet seems diverse, with at least 45 fish species from 18 families, plus crabs and river turtles, represented in examined stomach contents (Best, 1984). Both schooling and nonschooling fish species are eaten. Amazon dolphins are the only modern cetaceans with a differentiated dentition. The teeth in the front half of the jaw are conical, whereas those in the latter half have a flange on the inside portion of the crown, more reminiscent of molars (for crushing) than canines or incisors (for biting and holding). Presumably, this feature is related to the hard-bodied or spiny character of some of their prey (e.g., armored catfishes, even turtles); large catfish are often toni into smaller pieces before being eaten.

Irrawaddy dolphins engage in “cooperative fishing” with throw-net fishermen in Burma’s Irrawaddy River (Smith et al, 1997). The fishermen call the dolphins by repeatedly striking the sides of their canoes with a wooden pin. Then they slap the water surface with a paddle, utter a turkey-like call, and make several practice throws of the net. When conditions are favorable, the dolphins slap the surface with their flukes and begin herding the fish school toward the fishermen. With a signal from one of the dolphins (its partially submerged flukes waving laterally toward the fishermen), the net is thrown. According to the fishermen, catches made with the help of dolphins are consistently better that those made without their assistance. Not surprisingly, the animals are revered and protected by the residents of local fishing communities along the Irrawaddy.

III. Threats and Conservation Concerns

Any description of the river cetaceans must include a section on their conservation status. They are among the most endangered marine mammals (see Smith and Smith, 1998: Reeves et al, 2000). The Yangtze River dolphin is probably the most critically endangered cetacean species. Discovered by Western science as recently as 1918, it apparently was still common and widely distributed along the entire Yangtze River, from Three Gorges to Shanghai, when China’s Great Leap Forward began in the autumn of 1958. From that time, the baiji was hunted intensively for meat, oil, and leather. Although legally protected, Yangtze dolphins continue to die accidentally in fishing gear, from collisions with powered vessels, and from exposure to underwater blasting during harbor construction. This mortality, combined with the effects of overfishing, pollution, industrial and vessel noise, and the damming of Yangtze tributaries, has driven the baiji population to the brink of extinction. Only a few tens of individuals are thought to survive. The finless porpoise that share much of this river dolphin’s historical range have also been declining rapidly in recent years, presumably for the same reasons. Efforts to protect both species have been far from adequate. As the controversy surrounding construction of the Three Gorges Dam in the upper Yangtze River has eloquently demonstrated, China is committed to a course that places further industrial development of the Yangtze basin far ahead of preserving the natural environment (Zhou et al., 1998).

The Indus and Ganges dolphins are also classified as endangered, with the former numbering about a thousand and the latter possibly in the low thousands. Indus dolphins occur today only in the main channel of the river, although historically they inhabited several large tributaries as well (Sutlej, Ravi, Chenab, and Jhelum). Their population has been fragmented by irrigation dams, and the subpopulations trapped up-river of these dams have progressively gone extinct. Now, only three subpopulations of Indus dolphins are large enough to be considered potentially viable. The Ganges dolphin has also lost large segments of upstream habitat as a result of dam construction, but its generally broader distribution has meant that it is less immediately threatened with extinction. Like the baiji and Yangtze finless porpoise, the Indus and Ganges dolphins are subjected to incidental capture in fishing gear, especially gill nets. An additional concern for the Ganges dolphin is that fishermen in some parts of India and Bangladesh use dolphin oil as an attractant while fishing for a highly esteemed species of catfish. This means that there is a demand for carcasses and a disincentive for releasing live dolphins found in nets. Some tribal people in remote reaches of the Ganges and Brahmaputra still hunt dolphins for food.

Ultimately, all river cetaceans are threatened by the transformation of their habitat to serve human needs. In addition to impeding the natural movements of dolphins and other aquatic organisms, dams in southern Asia divert water to irrigate farm fields and supply homes and businesses in an arid landscape, reducing directly the amount of habitat available to the dolphins. As water becomes an increasingly strategic resource in a warming world with burgeoning human populations, the prospects for river cetaceans are certain to deteriorate even further.