Because of their morphological similarities, the stocky dusky dolphin Lagenorhynchus obscurus from the Southern Hemisphere and the Pacific white-sided dolphin Lagenorhynchus obliquidens from the northern Pacific Ocean have long been recognized as phylogenetically closely related species despite the absence of a fossil record. Several researchers have gone so far as to suggest that the latter could almost equally well be regarded as a subspecies of the dusky dolphin. A close scrutiny of morphological and life history parameters, however, does not support this premise. Recent cytochrome b sequence analysis is consistent with the “sister-species” hypothesis, and the divergence date is estimated at 1.9-3.0 million years ago (Cipriano, 1997).

I. Pacific White-Sided Dolphin

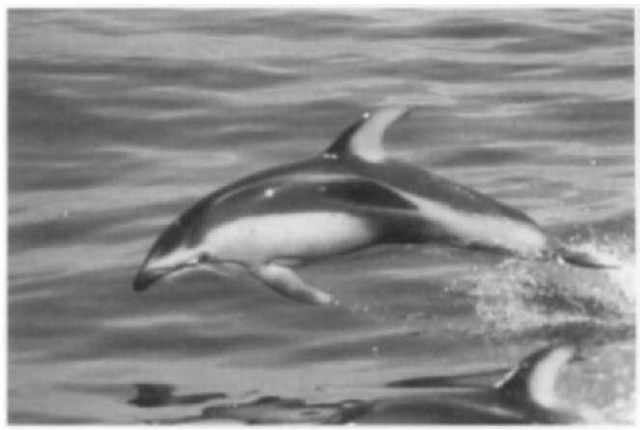

Described in 1865 by Theodore Gill from three skulls collected in California, the boldly colored Pacific white-sided dolphin is black or dark gray on the back and posterior sides, as well as on the short snout, the leading edge of the tall dorsal fin, and the pointed flippers. The light gray thoracic patch is sharply delineated from the white belly by a thin dark line, in contrast with the dusky dolphin, which lacks this line and a sharp demarcation. Gray, linear dorsal flank blazes, often called “suspender stripes, project forward from the grayish flank patches along the back and disappear above the eyes (Fig. 1). The average adult size is 2.1-2.2 m with a body weight of 75-90 kg. Exceptionally, a length of 250 cm (males) and 236 cm (females) can be reached (Walker et al., 1986) and a maximum weight of 181 kg, which is at least 50% heavier than the dusky dolphin.

A. Distribution

The mostly pelagic Pacific white-sided dolphin has a primarily temperate distribution across the North Pacific, from Taiwan to the Kurile and Commander Islands on the west and from 20-21°N to 61°N on the east, as well as more or less continuously across the North Pacific. Some seasonal shifts occur; while more common in coastal waters during fall and winter, these dolphins move offshore during spring and summer, in rough synchrony with movements of anchovy and other prey (Leatherwood et al., 1984; Walker et al., 1986).

No subspecies are recognized but either two or three populations are distinguished from the northeast Pacific and another two forms seem to exist in Japanese waters. L. ognevi named by Sleptsov in 1955 is a synonym of L. obliquidens.

Figure 1 The Pacific white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens) is usually found in pelagic waters of the North Pacific.

B. Behavior

These acrobatic dolphins often form large herds, averaging some 90 individuals, but groups of more than 3000 dolphins have been reported. Some segregation occurs based on sex and age. They readily associate with many other cetacean species and avidly bow ride. Generalist feeders, off California and Japan, L. obliquidens mostly prey on lantern fishes (Myctophi-dae), anchovies, hake, and squid (Fitch and Brownell, 1968); off British Columbia they feed on herring, salmon, cod, shrimp, and capelin (Heise, 1997a). Males and females become sexually mature at 170-180 and 175-186 cm, respectively. The calving season peaks during the summer, the gestation period is 1 year, and females reach sexual maturity at an estimated 7.5 years old (Heise, 1997b).

C. Abundance and Exploitation

Pacific white-sided dolphins are still fairly numerous; however, like for most delphinids, no total abundance estimates are available. On the continental shelf off northern and central California in the mid-1980s, a population of 85,000 dolphins was proposed, but a 1991-1993 estimate for the same general area amounted to only 11,200 (Barlow and Gerrodette, 1996).

While it is not taken in drive fisheries, Japanese fishermen for decades have harpooned at times large numbers. A single company, for example, landed 697 animals in May and June 1949. Nonetheless, precise catch statistics were not compiled until fairly recently, and the long-term effect of the exploitation on the western population has not been evaluated. At least tens of Pacific white-sided dolphins are taken each year incidentally to a variety of coastal fisheries off western North America. The now outlawed multinational pelagic driftnet fisheries in the North Pacific may have caused significant mortality, but reliable figures have not been published. Pacific white-sided dolphins have been maintained in captivity in the United States, Japan, and Canada, but survival rates have been low.

II. Dusky Dolphin

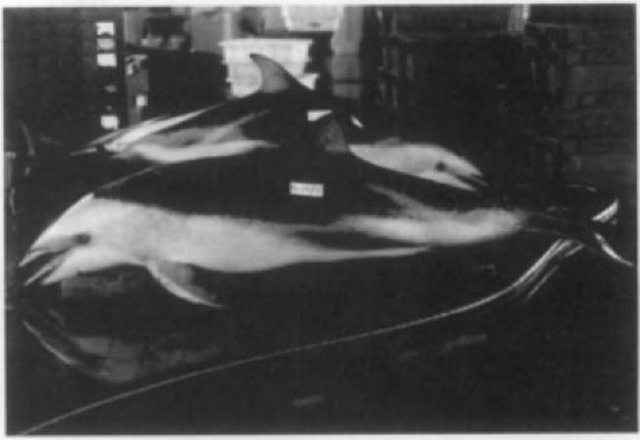

The dusky dolphin was described by John W. Gray in 1828 from a stuffed skin and a single skull shipped to the British Museum from the Cape of Good Hope. This smallish dolphin can be recognized by its short beak and the bluish black to dark gray of the dorsal field contrasting with the white belly, as well as die light gray of the thoracic patch and two-pronged flank patch (Fig. 2). The dark lips and eyepatch also stand out. The falcate dorsal fin is two-toned with a dark leading edge. Unlike in L. obliquidens, the linear dorsal flank blaze does not extend farther anteriorly than about midbody. Heavily pigmented specimens are found off Peru and Argentina. The holotype of Delphinus fitzroyi (Waterhouse, 1838) caught off Argentina from Darwin’s ship Beagle was such a melanized form. Both males and females off Peru reach sexual maturity at about 175 cm, while the largest two known individuals out of many hundreds measured 211 and 205 cm, respectively. They rarely exceed 100 kg in weight. No significant dimorphism is present except that adult males, much as in Pacific white-sided dolphins, have a significandy bigger and more strongly curved dorsal fin, presumably a secondary sexual characteristic.

Figure 2 The dusky dolphin (L. obscurus), which may be closely related to its northern congener, the Pacific white-sided dolphin, occurs in Southern Hemisphere waters in both the Atlantic and the Pacific..

Gestation lasts for some 13 months. In Peru and New Zealand, most births occur in winter but a few neonates appear during other seasons. In Argentina, summer is the prime birth season. In Peru, sexual maturity for females is estimated at 4.3-5 years and for males at 3.8-4.7 years. The lower values, which are the most recent, possibly indicate a density-dependent response to heavy exploitation (Chavez-Lisambarth, 1998). Female Patagon-ian dusky dolphins mature at 6.3 years of age (Dans et al., 1997).

A. Distribution

Dusky dolphins are distributed around South America, from northern Peru soudi to Cape Horn and from southern Patagonia north to about 36°S, including the Falkland Islands; off soudi-western Africa from False Bay to Lobito Bay, Angola; and in New Zealand waters, including off Chatham and Campbell Islands. Populations of unknown size inhabit waters surrounding oceanic islands of the Tristan da Cunha archipelago in the mid-Adantic, the Prince Edward Islands, and Amsterdam Island in the south-em Indian Ocean (Van Waerebeek et al., 1995). Dusky dolphins have been confirmed from southern Australia but seem to be rare diere. Their coastal habits explain die discontinuous distribution across the temperate southern ocean, reproductive isolation, and cranial differences at a subspecific level (Brownell and Cipriano, 1999). Dusky dolphins from southwest Africa and New Zealand are some 8-10 cm shorter than the ca. 185 cm average adult body size of Peruvian specimens of both sexes (Van Waerebeek, 1993).

B. Behavior

Although dusky dolphins can move over great distances—a range of 780 km is confirmed—no well-defined seasonal migration patterns are apparent. However, the Argentina and New Zealand populations exhibit inshore-offshore movements both on a diumal and on a seasonal scale. Dusky dolphins over the extensive continental shelf of Patagonia forage cooperatively on small schooling fishes during the day. On the east coast of New Zealand, where deep oceanic waters reach close to shore, animals typically feed at night on prey associated with the deep scattering layer (Wiirsig et. al, 1997). Some of these same dolphins, identified by natural marks on their bodies, have been found to feed cooperatively during daytime in the Marlborough Sounds on the northern edge of the South Island of New Zealand, reinforcing a generally held belief that these animals adapt be-haviorally relative to habitat and prey availability patterns. Prey items include a variety of smaller fish; however, the diet everywhere tends to be dominated by anchovies, hakes, and several squid species. Surface feeding activity typically happens in large groups accompanied with extensive aerial display. It is believed that such aerial activity helps synchronize cooperative foraging and after-feeding social (including sexual) activities (Wiirsig et al, 1989). Anomalous dentine deposition during El Nino years off Peru may reflect low foraging success. Killer whales (Orcinus orca) and some sharks are the only confirmed predators; dusky dolphins will enter very shallow water to avoid killer whales.

C. Abundance and Exploitation

In die absence of reliable abundance estimates, the species’ status is indeterminate. Unknown numbers are caught in gill nets in New Zealand waters, although current catches have dropped from those of the 1970s and 1980s. Off Argentina, from 1982-1994, a variable number of Patagonian dusky dolphins, typically a few hundred each year, died in midwater trawls. Arguably of biggest concern are fishery-related mortality levels in Peruvian coastal waters, where both directed and accidental entanglements in artisanal drift nets, as well as harpooning, have killed thousands each year since 1985. In the 1991-1993 period, an estimated 7000 animals per annum were captured, an exploitation thought to be unsustainable. It is believed but not confirmed that this level of human-caused mortality has dropped off in recent years, partly due to conservation legislation and partly because of the depletion of the population. Only a few individuals have been exhibited in aquaria in New Zealand, South Africa, and Australia, largely because dusky dolphins adapt rather poorly and have failed to reproduce successfully in captivity.