One of the most unexpected recent discoveries in marine mammal paleontology is that of a new family and genus of tusked cetacean—Odobenocetopsidae, Odobenocetops—from the early Pliocene beds of the Pisco Formation of Peru (Muizon, 1993; Muizon et al, 1999). As its name indicates, the new marine mammal presents several similarities with the living walrus, Odobenns rosmanis. However, Odobenocetops is clearly a cetacean and presents a startling and unprecedented example of convergence with the walrus in its cranial morphology and inferred feeding habits (Muizon, 1993; Muizon et al, 1999). Odobenocetops is known from two species: O. pertwianus, Muizon, 1993, and O. leptodon, Muizon, Domning, and Parrish, 1999, with the former being slightly older than the latter.

I. Descriptive Anatomy

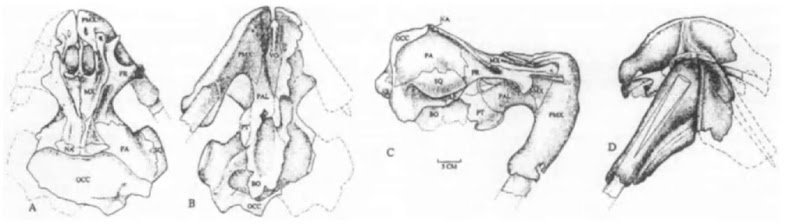

Odobenocetops (Figs. 1-3) has lost the elongated rostrum of the other cetaceans. Instead, the rostrum is short, rounded, and blunt and formed by the premaxillae, which are greatly enlarged. They have large, asymmetrical ventral alveolar sheaths holding sexually dimorphic tusks. The right tusk of the male is large and can reach 1 m or more in length. The left tusk is approximately 25 cm long, of which a few centimeters only were erupted. Both tusks are straight. In the female, both tusks approach the size of the left tusk of the male, although the right tusk is slightly larger than the left. Premaxillary sheath and tusks are oriented posteroventrally. The bony nares have displaced anteriorly (when compared to other odontocetes). The palate is very deep and arched, and its anterior border is U to V shaped. Odobenocetops lacks maxillary teeth. The orbits face anterolaterally and dorsally. The portions of the frontal and maxillae, which cover the temporal fossae in other odontocetes, have been reduced and narrowed in such a way that the temporal fossae are opened dorsally. The glenoid cavity is an an-teroposteriorly elongated groove. The occipital condyles are very salient and more convex than in any other Pliocene or living cetaceans. The periotic and tympanic have the characteristic morphology observed in other delphinoid cetaceans. The mandible is unknown. The postcranial skeleton is poorly known. The atlas is shortened anteroposteriorly as in other odontocetes, and the forelimb has the basic pattern of that of other odontocetes. The length of the body could have ranged from 3 to 4 m.

II. Affinities

Despite its extremely modified morphology, several characters of the skull clearly relate Odobenocetops to the delphinoid cetaceans. Cetacean characters of Odobenocetops include the presence of large air sinuses in the auditory region connected to well-developed pterygoid sinuses; the thickened and pachyostotic tympanic bulla; and the dorsal opening of the nar-ial fossae. Odontocete affinities of Odobenocetops are attested by maxillae covering the supraorbital processes of the frontals, although they are partially withdrawn secondarily; the dorsoven-tral expansion of the pterygoid sinuses; the presence of large premaxillary foramina (in O. pemvianus only); and the asymmetry of premaxillae and maxillae in the facial region. The sigmoid morphology of the dorsomedial view of the involucrum and the presence of a medial maxilla-premaxilla suture at the anterolateral edge of each narial fossa are delphinoid characters (Muizon, 1988). Several characters of the pterygoid, al-isphenoid, and temporal fossa indicate close affinities of Odobenocetops and the Monodontidae (Muizon, 1993; Muizon et al, 2000). In view of the exceptional specializations of Odobenocetops, it was referred to as a new odontocete family, the Odobenocetopsidae, regarded as the sister group of the Monodontidae.

Figure 1 Odobenocetops peruvianus: Skull of a male in dorsal (A), ventral (B), lateral (C), and anterior (D) views. Scale bar: 5 cm. AP, alisphenoid; BO, basioccipital; FR, frontal; MX, maxilla; NA, nasal; OCC, occipital; PA, parietal; PAL, palatine; PMX, premaxilla; PT, pterygoid; SQ, squamosal; VO, vomer.

The occurrence of tusks in Odobenocetops is a convergence with Monodon as in the latter genus the large tusk of the male is implanted in the left maxilla, whereas in Odobenocetops it is implanted in the right premaxilla. Consequently, the tusks of Monodon and Odobenocetops are not homologous.

III. Functional Anatomy and Habits

A. Feeding Adaptations

Odobenocetops and the living walrus show several morphog-ical convergences: a large and deep palate; strong development of a wide, blunt snout, which is highly vascularized and innervated with strong muscular insertions, suggesting the presence of a powerful tactile upper lip; the presence of tusks; and a reduction of maxillary dentition (postcanine maxillary teeth are absent in the fossil walrus Valenictus clmlavistensis). The living walrus feeds mainly on benthic invertebrates (e.g., Mya, Clinocardium, Tellina, Spisula, Macoma) (Fay, 1982), sucking out the siphon and foot of bivalves or gastropods shells, using the tongue as a piston powered by the very large lingual retractors and depressors. Their mouth works like a powerful vacuum pump. Given the anatomy of its palate, it is likely that Odobenocetops presented a similar feeding adaptation. This adaptation was probably even more efficient in O. leptodon because its palate is longer than in O. peruvianus. Odobenocetops therefore probably fed on benthic invertebrates (bivalves and gastropod mollusks and/or crustaceans), which are abundant in the Pisco Formation at Sacaco. Because of the great vascularization of the inferred upper lip, it is possible that, as in the walrus, Odobenocetops had vibrissae, which would have had an important tactile role in the search for food. When feeding on the sea floor, the body of Odobenocetops was probably held in an oblique position as is observed in the living walrus (Fig. 4).

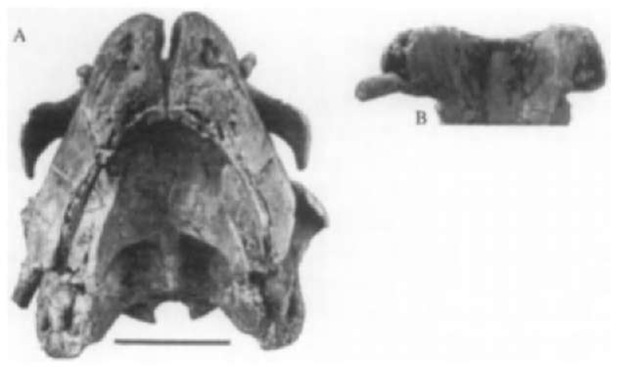

Figure 2 Odobenocetops peruvianus: skull of a female in an-teroventral view (A); ventral view of the anterior region of the palate of the same skull (B). Scale bar: 5 cm.

Figure 3 Odobenocetops leptodon: skidl of a male in left ventrolateral (A), anteroventral (B), dorsal (C), and left lateral (D) views. Scale bar: 20 cm (A, B); 10 cm (C, D).

B. Vision vs Echolocation

Vision and hearing were probably slightly different in the two species of Odobenocetops. Because of the shortening of the rostrum and the very short space between the premaxillary foramina and the nares, it is probable that the premaxillary air sacs in O. peruvianns were absent, unlike in other odontocetes. Furthermore, a melon was also probably absent or very reduced. In contrast, in O. leptodon, fossae for premaxillary sacs are clearly present on the premaxillae, just anterior to the nares as are observed in other odontocetes. Furthermore, the dorsal surface of the rostrum is longer and wider and there is enough space for a small melon anterior to the nares. The cetacean melon is related to echolocation and, consequently, O. peruvianus was probably devoid of echolocating ability, whereas some echolocating ability may have been present in O. leptodon.

Figure 4 Reconstruction of Odobenocetops leptodon (males) in swimming and feeding position. The third individual in the background is in ventrolateral view from the left side in order to show the erupted small left tusk.

The anterodorsal edge of the orbit (i.e., the anterior border of the supraorbital process of the frontal) in O. peruvianus is deeply notched, allowing good anterodorsal binocular vision. In contrast, this region of the frontal in O. leptodon is only slightly concave, which reduced binocular vision.

The probable lack of echolocation ability in O. peruvianus, was probably compensated for by good anterodorsal binocular vision. As in the walrus, vision was especially useful when the animal was searching for food on the sea flood with the body in an oblique position. In O. leptodon, limited binocular vision was compensated for by echolocation ability as in other odontocetes.

C. Tusk, Position and Function

The posteroventrally oriented tusks are certainly one of the most unusual characteristics of Odobenocetops. Because of its great length and slenderness, the right tusk of the male was probably very fragile and it was unlikely that the animal swam with the tusk held at a 45° angle with the axis of the body. Comparison of the occipital condyles to the anterior articular facets of the atlas indicates that, when swimming, the dorsal plane of the skull was oriented anterodorsally and that the tusk was approximately parallel to the axis of the body. When feeding, the large tusk was dragged on the sea floor, and because of the oblique position of the body, the tusk was held at an angle of 20° to 40° with the axis of the body (Fig. 4). In other respects, the convexity of the occipital condyles of Odobenocetops indicates that its neck was extremely mobile, allowing a degree of head movement approaching 90° or more.

The narwhal tusk is mainly used in social activities. The orientation and length of the large tusk of Odobenocetops suggest that this tooth was very fragile and was unlikely to have been used to exert forces (in digging or fighting). The probable sexual dimorphism in the size of the tusks of O. peruvianus points to a nonviolent social role (Muizon et al, 2001). In addition, the tusks of walruses and the premaxillary tusks and sheaths of Odobenocetops may play a role in bottom feeding as orientation guides to keep the mouth and any vibrissae (if present) in constant position relative to the substrate.

Although suction feeding has been increasingly recognized among odontocetes (e.g., Tursiops, Globicephala, Phocoenoides, Phocoena, Monodon, Delphinaptems, Physeter, Mesoplodon, Berardius), the extreme modifications of Odobenocetops are unique among the Cetacea and suggest concomitant expansion of the adaptive breadth of the order. Odobenocetops occupied, in the Southern Hemisphere, an ecological niche otherwise unknown among odontocetes that was similar to that of the odobe-nine walruses, which were widespread in the Northern Hemisphere during the Pliocene.