Kentriodontidae is the most diverse family of archaic delphinoids in terms of morphology, geographic range, and * temporal range. Unfortunately, while they are the best-studied archaic delphinoids, there are still many unanswered questions about this group, including the veiy basic question of whether kentriodontids are monophyletic (Muizon, 1988). The grade-level family Kentriodontidae has essentially been defined based on its members holding an intermediate position between primitive odontocetes and modem delphinoids. Additionally, no computer-aided cladistic analysis has described the relationships of taxa attributed to the Kentriodontidae.

I. History

Kentriodontids have a long history in the science of paleontology. The specimen now known as Lophocetus calvertensis was first described by Harlan in 1842 as Delphinus calvertensis (diis is an early example of a fossil odontocete being taxo-nomically lumped with a modem genus). The family takes its name from Kentriodon pernix, described by Kellogg in 1927. Slijper named the subfamily Kentriodontinae in 1936 and considered it to be within the family Delphinidae. Barnes (1978) articulated the modern concept and classification of the family Kentriodontidae as distinct from but related to modern delphinoids. Subsequent studies (Muizon, 1988; Dawson, 1996) have been based on that classification.

II. Morphology

Archaic delphinoids resemble modern delphinoid species in general body morphology. Hindlimbs are absent, forelimbs are modified to form paddle-like flippers, and the rostrum is elongated to form a pronounced snout or beak in most species. Differences between archaic and modem delphinoids are apparent in features such as skull proportions and morphology, development of basicranial sinuses, tooth number and morphology, and vertebral number and proportions. Each of these features has primitive and derived character states, which are distributed among archaic and modem delphinoids.

Among modem delphinoids, there is a range of variation of flipper shapes, from the narrow flippers of the common dolphins (Delphinus spp.), to the wider flippers of the beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas), to the wide ovoid flippers of the killer whale (Orcinus orca). Forelimb bones are known from only a few species of archaic delphinoids, making prediction of fossil flipper morphology tenuous. The humerus, radius, and ulna are known from Hadrodelphis, and the articular surfaces of these bones suggest that the flipper was wide, although without the bones of the manus it is impossible to predict the exact width.

Morphology of the cervical vertebrae is known from a few species (such as Hadrodelphis calveriense) and indicates that the cervical vertebrae of archaic delphinoids are less compressed along the cranio-caudal axis than the cervical vertebrae of modem delphinids and phocoenids. In these modem species, the cervical vertebral bodies are extremely thin and may be fused together, making the neck relatively rigid and veiy short. The increased length of die cervical vertebral bodies in archaic forms suggests that the neck was more elongate and mobile in these species, perhaps comparable to modem beluga whales. Different kentriodontid taxa also exhibit a range of vertebral centrum proportions in other regions of the vertebral column. While no species has lumbar vertebral centra elongated to the extreme extent found in some archaeocetes, some species such as Kentriodon pernix do have more elongated vertebral bodies than species of Atocetus. Differences in vertebral centrum proportions may have functional significance, a concept which has been explored by Buchholtz (1998). Individuals with relatively long vertebral centra may have had more flexible vertebral columns and may have been slower, more maneuverable swimmers, such as the modem beluga whale. Individuals with shorter, more compressed vertebral centra may have more rigid vertebral columns and may be faster swimmers, such as the modem Dall’s porpoise.

Kentriodontids have been traditionally divided into three groups (Table I). Kentriodontines include the genera Kentriodon, Delphinodon, and Macrokentriodon. These genera have a cranial vertex morphology which is relatively flat and tabular. There is broad exposure of the nasal and frontal bones at the vertex, but the nasal bones are not enlarged or inflated, nor is the vertex significantly elevated. Lophocetines include the genera Lophocetus, Liolithax, and Hadrodelphis and have nasal bones that are more elongate and the cranial vertex slightly to significantly elevated. Pithanodelphines (including the genera Pithanodelphis and Atocetus) have large, inflated nasal bones. With the exception of some pithanodelphines, kentriodontids demonstrate the primitive condition of cranial symmetry; this feature is in contrast to modern delphinids, in which the cranial vertex is markedly asymmetrical and the left premaxilla does not contact the left nasal bone.

TABLE I

Classification of Archaic and Modern Delphinoids. with Temporal and Geographic Distributions”

Order Cetacea Brisson, 1762

Suborder Odontoceti (Flower, 1864)

Superfamily Delphinoidea (Gray, 1821)

Family Kentriodontidae (Slijper, 1936)

Subfamily Kentriodontinae (Slijper, 1936)

Late Oligocene-Middle Miocene; eastern and western North Pacific, western South Pacific, western South Atlantic, western North Atlantic oceans) Kentriodon Kellogg, 1927

Macrokentriodon Dawson, 1996

Delphinodon (True, 1912)

Subfamily Lophocetinae Barnes, 1978 (Middle Miocene-Late Miocene; eastern North Pacific, western North Atlantic oceans) Lophocetus (Harlan, 1842) Liolithax Kellogg. 1931

Hadrodelphis Kellogg, 1966

Subfamily Pithanodelphinae Barnes, 1985 (Middle Miocene-Late Miocene; eastern North Pacific, eastern South Pacific, eastern North Atlantic oceans) Pithanodelphis Abel, 1905 Atocetus Muizon, 1988

Family Albireonidae Barnes, 1984 (Late Miocene-Early Pliocene; eastern North Pacific ocean) Albireo Barnes, 1984

Family Monodontidae Gray, 1821 [Late Miocene-Recent; eastern North Pacific (Late Miocene-Pliocene), circumpolar Arctic]

Family Delphinidae Gray, 1821 (Late Miocene-Recent; all oceans)

Family Phocoenidae (Gray, 1825) (Late Miocene-Recent; all oceans)

“Kentriodontid genera of uncertain affinity are not included in this classification.

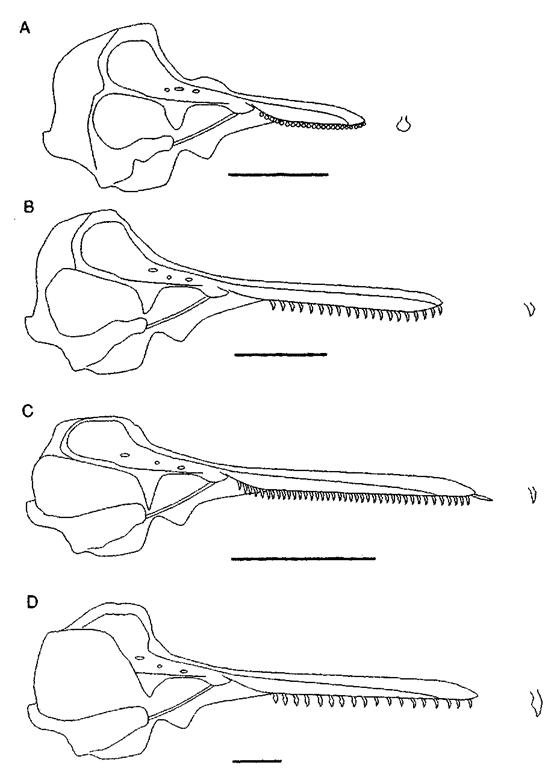

While primitive odontocetes retained heterodont teeth, archaic delphinoids (as well as other Oligocene-Miocene odontocetes such as eurhinodelphids) mark the transition to the poly-dont, homodont dentition found in modern delphinids (Fig. 1). There is variation in the number of teeth in different species, but all kentriodontids have a tooth count that is increased beyond the generalized mammalian condition. Kentriodontids do not have the large, triangular, double-rooted cheek teeth of the Squalodontidae. Instead, all teeth are conical in shape and have a single root. Modern phocoenids also have a homodont dentition with single-rooted teeth, but the crowns of these teeth are spatulate rather than conical (Fig. 1A). There is no evidence of this tooth morphology in any kentriodontid, nor is it present in the earliest phocoenids. Kentriodon demonstrates an unusual morphology, with the most anterior premaxillary teeth elongate and procumbent, oriented in a horizontal rather than vertical plane (Fig. 1C). Some kentriodontid taxa, such as Hadrodelphis and Knmpholophos, exhibit variation within the tooth row, such that more posterior teeth have a shelf-like projection on the lingual surface and a series of small cuspules (Fig. ID). Anterior teeth are smooth and conical. This slightly heterodont condition is also found in modern Iniidae, the boto of the Amazon River (lnia geoffremis), and is part of the evidence that led paleontologists to hypothesize relationships between archaic delphinoids and river dolphins. Further investigations of odontocete relationships, however, have focused on more diagnostic cranial characters than dentition and confirmed the relationship of kentriodontids with modern delphinoids.

Modern and archaic delphinoids exhibit wide variation in rostrum length (Fig. 1). Species such as the long-beaked Hadrodelphis have a rostrum that is approximately two-thirds the total length of the skull (Fig. ID). Short-beaked species such as Delphinodon dividum have a rostrum that is only one-half the total skull length. Although there is also a range of variation between genera, monodontids and phocoenids tend to have shorter rostra than delphinids (Fig. IB), and all three modern families tend to have shorter rostra than long-beaked kentriodontids. The short rostra of phocoenids (Fig. 1A) may be associated with paedomorphic modifications postulated for this group (Fordyce and Barnes, 1994). Longer rostra are found in the river dolphins, including platanistids, pontoporiids, lipotids, and iniids. No living odontocete possesses a rostrum as long as that of the bizarrely long-beaked eurhinodelphids, which had a rostrum four-fifths (or more) the total length of the skull.

III. Taxonomic, Temporal, and Geographic Diversity

The fossil record of modern delphinids, phocoenids, and monodontids extends to at least the Late Miocene (Table I). As a family, the modern Delphinidae are cosmopolitan in distribution, with individual genera having a more restricted range. The earliest fossil delphinids are reported from eastern North Pacific deposits of the Late Miocene. Barnes (1990) summarized the evolutionary history of the bottlenose dolphin, Tur-siops truncatus. The genus is known from at least the early Pliocene, and possibly from the latest Miocene. Fossil species of Ttirsiops are widely distributed, having been reported from Atlantic, Pacific, and Mediterranean deposits.

Modern phocoenids are widely distributed in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, but are not found in all regions of those oceans. The earliest Phocoenidae are known from the Late Miocene. Early phocoenid fossils are reported from the western coasts of North and South America, and this group may have originated in the Pacific basin.

Extant monodontids are restricted in distribution and diversity when compared to fossil members of this family. There are two living monodontids, the beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) and the narwhal (Monodon monoceros), both of which are found only in circumpolar waters of the Arctic. The earliest fossil monodontids are reported from the Late Miocene. Fossil monodontids showed greater taxonomic diversity and had a much different geographic distribution; they are reported from the Late Miocene and Pliocene of California and Baja Mexico.

Figure 1 Skull and tooth morphology of niodern and fossil delphinoids. Scale bar: 10 an. (A) Family Phocoenidae, Phocoena phocoena; (B) Family Delphinidae, Tursiops truncatus; (C) Family Kentriodontidae, Kentriodon pernix (fossil, reconstructed); and (D) Family Kentriodontidae, Hadrodelphis calvertense (fossil, reconstructed).

The family Kentriodontidae is often described as cosmopolitan in geographic distribution, with a temporal range from the Late Oligocene to Late Miocene. However, because the group may not be monophyletic, the distribution of “Kentriodontidae” may be a spurious and irrelevant question. It is perhaps more meaningful to first examine the distribution of individual taxa and the taxonomic distribution of species within genera.

A. Interpreting the Fossil Record of Kentriodontids

All studies of fossil organisms are necessarily limited by the quality of available specimens. This problem is particularly acute with kentriodontids, as there is a lack of described specimens as well as a lack of specimens represented by diagnostic, comparable material. While it is preferable for holotype specimens to consist of a skull and associated periotic, several kentriodontid taxa have been named based on isolated periotics or teeth. Analyzing the distribution of individual species of kentriodontids is particularly problematic due to the paucity of specimens. Most taxa are known only from the holotype material, making it difficult to account for individual variation; e.g.. eight genera of kentriodontids are reported from North America, but only two of these genera are known from more than one skull (Dawson, 1996). There is little evidence of an individual species being known from more than one ocean basin or region. The sole published example of one species described from more than one basin or region are two specimens referred to as “aff. Delphinodon dividum” from the Middle Miocene of California and Japan; both of these specimens consist of isolated periotics, making this designation problematic.

B. Diversity of Kentriodontid Species

The distribution of genera both geographically and temporally is slightly less problematic. There are 16 genera included in the family; of these only 5 genera have more than one published species. The proper generic assignment of at least two of these species is questionable. There are two species formally assigned to the genus Hadrodelphis: H. calvertense and H. posei-doni. Hadrodelphis poseidoni, however, is questionable because it is based only on isolated teeth. The genus Lophocetus has also undergone considerable revision. There are currently two species formally assigned to the genus Lophocetus. Both species, L. calvertensis and L. repenningi, are represented by a skull with periotics. However, Muizon has questioned the generic assignment of L. repenningi, suggesting that it does not belong in that genus. Kellogg originally assigned Liolithax pappus to the genus Lophocetus, but Barnes’ 1978 revision of the kentriodontids placed it in its currently accepted genus. The type species of the genus Liolithax is L. kernensis Kellogg 1931, which is described on the basis of isolated periotics. No cranial or postcra-nial material has been formally referred to L. kernensis.

The two species of the genus Atocetus offer a well-founded example of temporal and spatial diversity of a kentriodontid genus. A. nasalis is reported from the eastern North Pacific basin, whereas A. ic/uensis is reported from the eastern South Pacific. Both species are described from several diagnostic specimens.

The genus Kentriodon is the most diverse of the kentriodontids, with three named species and at least five unde-scribed species mentioned in the literature. It is the oldest described kentriodontid genus, reported from the Late Oligocene to the Middle Miocene; it is not reported from the Late Miocene (Ichishimaet al, 1994). Kentriodon also has the widest geographic range, reported from the eastern and western North Pacific, eastern and western South Pacific, western North Atlantic, and western South Atlantic. It has not been reported from the eastern North Atlantic, although most kentriodontids reported from this region are Late Miocene in age.