The blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus (Linnaeus, 1758), – is a baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenopteri-* dae, which includes the group of cetaceans known as rorquals (Fig. 1). Common names are blue whale, sulfur-bottom, Sibbald’s rorqual, great blue whale, and great northern rorqual. The largest animal known to have existed on Earth, it is found worldwide, ranging into all oceans. Because of its great size and the commercial value of the products it yielded, the blue whale was hunted relentlessly beginning in the late 1800s. The greatest number of blue whales was taken from the early 1900s until the late 1930s, with the peak being in the 1930-1931 season when nearly 30,000 were killed. The height of blue whale whaling coincided with the advent of explosive harpoons, steam power vessels, and the construction of factory ships, which could process whale carcasses at sea. The blue whale was severely depleted by whaling, particularly in the Southern Hemisphere, where during the first half of the 20th century 325,000-360.000 were killed in Antarctic waters alone. A further 11,000 were taken in the North Atlantic, primarily in Icelandic waters and 9500 in the North Pacific. This unbridled hunt for blue whales, which lasted until its worldwide protection in 1966, brought the blue whale to the brink of extinction and it is still an endangered species today.

I. Diagnostic Characters

On average, Southern Hemisphere blue whales are larger than Northern Hemisphere animals, widi the largest recorded at lengths of 31.7-32.6 m (104-107 feet) and 33.6 m (110 feet) for individuals caught off the South Shetlands and South Georgia. The largest blue whale recorded for the Northern Hemisphere was a 28.1-m (92 feet) female reported in whaling statistics from catches in Davis Strait. In the North Pacific female blue whales of 26.8 m (88 feet) and 27.1 m (89 feet) have been recorded. A 190-ton female was reported taken off South Georgia in 1947; however, body weights of adults generally range from 80 to 150 tons. For maximum size descriptions, female measurements are used because female baleen whales are larger dian males.

Blue whales are observed most commonly alone or in pairs; however, concentrations of 50 or more can be found spread out in areas of high productivity. Blue whales project a tall (up to 10-12 m) spout, denser and broader than that of the fin whale, (B. physalus) which in calm conditions can help distinguish between the two species. When surfacing, the blue whale raises its massive shoulder and blowhole region out of the water more than other rorquals. The prominent fleshy ridge just forward of the blowhole, known as the “splash guard,” is strikingly large in this species.

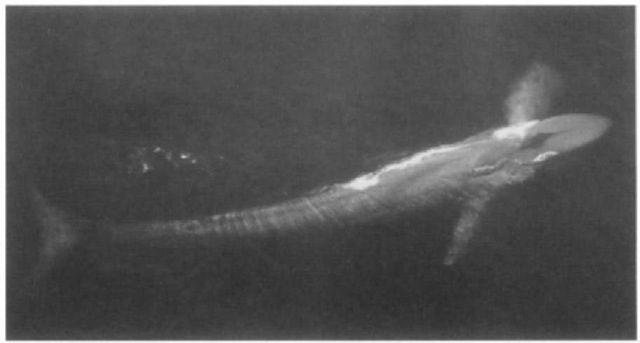

When seen from above, blue whales have a tapered elongated shape, with a huge broad, relatively flat, U-shaped head, adorned by a prominent ridge from the splash guard to the tip of the upper jaw or rostrum and massive mandibles (Fig. 2). The baleen is black, half as broad as its maximum 1-m length and 270-395 plates can be found on each side of the upper jaw (Yochem and Leatherwood, 1985). There are 60-88 throat grooves or ventral pleats running longitudinally parallel from the tip of the lower jaw to the navel, which enable the throat or ventral pouch to distend when feeding.

The dorsal fin, proportionally smaller than in other balaenopterids, yet varied in shape, ranging from a small nubbin to triangular and falcate, is positioned far back on the body.

Blue whales have long blunt-pointed flippers, slate gray, with a thin white border dorsally and white ventrally, reaching up to 15% of their body length. In the field, particularly on bright days, blue whales generally appear much paler in coloration than all species of large whale except for the gray (Eschrichtius robustus), with which it should not be confused due to a great difference in size.

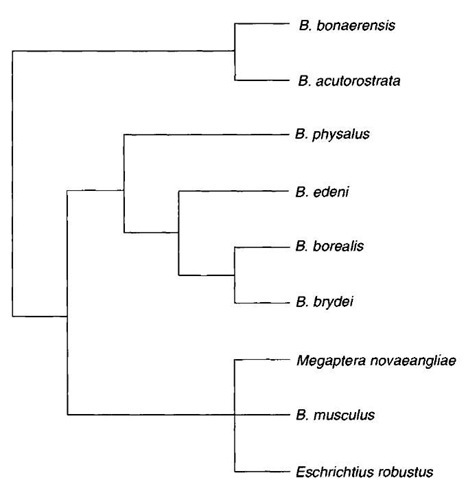

Figure 1 Phylogenetic relationships among the species of the genera Balaenoptera, Megaptera. and Eschrichtius based on several DNA sequencing studies.

The characteristic mottled pigmentation of blue whales is a blend of light and dark shades of gray displayed in patches of varying sizes and densities (Fig. 3). The pigmentation is slate blue on overcast days to silvery or turquoise blue on bright sunny days depending on the clarify of the water. The mottling is found along the body dorsoventrally, occasionally on the flippers, but not on the head and tail flukes. Two prominent pigmentation configurations are found in blue whales, one where a darker, dominant background is mottled with sparser pale patches of pigmentation, while in the other there is a predominantly pale background mottled with sparser dark patches. Blue whale pigmentation can vary, however, from very sparse mottling, where the individual appears uniformly pale or dark, to densely mottled individuals, where the pigmentation is a highly contrasted variegation of spots unique to each whale. Distinct chevrons curving down and angled back from the apex on both sides of the back behind the blowholes and either pale or dark in tone can be found on certain blue whales. Blue whales are individually identified from the distinctive mottled pigmentation found on their back and sides.

Figure 2 Blue whale, aerial view.

Figure 3 Blue whale showing the characteristic mottled pigmentation of the species.

A yellow-green to brown cast, caused by the presence of a diatom (Cocconeis ceticola) film, can be seen covering all or part of the body of blue whales found in cold waters. The yellowish, diatom-induced tint is the reason the “sulphur-bottom” moniker was once used for blue whales.

Although not noted for raising their flukes when diving, approximately 18% of blue whales observed in the western North Atlantic and northeast Pacific do so. This is an individual characteristic, and if the individual is relaxed it will generally raise its flukes high up in the air on each sounding dive. When disturbed, blue whales that raise their flukes when diving will often not raise their tails as high out of the water or not at all and dive more quickly from the surface. The tail flukes, sometimes striated ventrally, are predominantly gray above and below; however, some individuals do have white patches of pigmentation on the ventral surface that are used for individual identification. The trailing margin of the tail is either straight or curves very slightly from each tip to the median notch.

II. Distribution and Migration

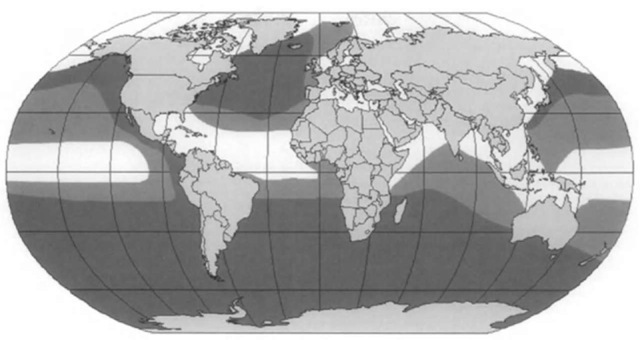

Three subspecies have been designated: what has been considered the largest, B. musculus intermedia, found in Antarctic waters; B. musculus musculus in the Northern Hemisphere; and B. muscidus brevicauda, from the subantartic zone of the southern Indian Ocean and south western Pacific Ocean, also colloquially known as the “pygmy” blue whale. Although the latter designation is now generally accepted, its validity still remains in question. Despite having being reduced greatly due to whaling, the blue whale remains a cosmopolitan species separated into populations from the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Hemisphere (Fig. 4). In the North Atlantic, eastern and western subdivisions are recognized. Photo-identification work from eastern Canadian waters indicates that blue whales from the St. Lawrence, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New England, and Greenland all belong to the same stock, whereas blue whales photo-identified off Iceland and the Azores appear to be part of a separate population. The best known population in the North Atlantic is that found in the St. Lawrence from April to January, where 350 individuals have been catalogued photographically. Apart from the Icelandic and Azores sightings, few blue whales have been reported from eastern North Atlantic waters recently. North Atlantic blue whale abundance probably ranges from 600 to 1500 at this time, although more extensive photo-identification and shipboard surveys are needed for more reliable estimates.

In the North Atlantic, blue whales reach as far north as Davis Strait and Baffin Bay in the west, while to the east they travel as far north as Jan Mayen Island and Spitzbergen during summer months. Blue whales sighted recently in winter and spring off the Azores and Canary Islands could be migrating north along the mid-Atlantic ridge to Iceland, where they are seen from May to September. Other blue whales probably migrate along the European coast, far offshore and out around Ireland north to either Iceland or Norway. It is not clear where blue whales winter in the North Atlantic. Some have been observed in the St. Lawrence as late as February; however, acoustic studies have revealed that they are spread out across the North Atlantic basin, south as far as Bermuda and Florida, with concentrations south of Iceland, off Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. The southernmost observations on the eastern side of the North Atlantic are in the waters between the coast of Africa and the Cape Verde Islands (Yochem and Leather-wood, 1985).

In the North Pacific, where as many as five subpopulations were thought to exist, acoustic analysis of blue whale vocalizations now indicates there are no more than two. The best known is that from the eastern North Pacific where blue whales can be found as far north as Alaska, but are regularly observed from California in summer, south to Mexican and Costa Rican waters in winter. An abundance estimate of approximately 2000-3000 animals has been determined for this population, which has been studied extensively over a good portion of its range. From late fall to spring, blue whales can be found in the Gulf of California, Mexico, and south to offshore waters of central America. By April and May they migrate north along the West coast of North America, where a large proportion is found in California waters. From there some reach Canadian waters, and other groups may disperse north to the Gulf of Alaska or west toward the Aleutian Islands.

Few blue whales have been reported recently from the western North Pacific, including the Aleutian Islands, Kam-chatka/Kurils/northern Japan, and southern Japan. In the western North Pacific, blue whales are thought to migrate to Kamchatka or the Kuril Islands and probably further northeast.

Blue whales are also found in the northern Indian Ocean; however, it is not clear whether these form a distinct population.

In the Southern Hemisphere, where the blue whale was historically most abundant, it is very rare today, with abundance estimates ranging from 710 to 1255, although reliable population assessment is poor due to limited sighting data. Al though the general population structure in the Southern Ocean is not well understood, evidence shows discrete feeding stocks. Consistent with these feeding areas, the International Whaling Commission has assigned six stock areas for blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere.

Figure 4 Global distribution of blue whales. Darker gray indicates higher densities.

III. Natural History and Ecology A. Feeding

Food availability probably dictates blue whale distribution for most of the year. Although blue whales can be found in coastal waters of the St. Lawrence, Gulf of California, Mexico, and California, they are found predominantly offshore. Blue whales appear to feed almost exclusively on euphausiids (krill) worldwide in areas of cold current upwellings. When blue whales locate suitably high concentrations of euphausiids, they feed by lunging mouth wide open and gulping large mouthfuls of prey and water. The mouth is then almost completely closed and the water is expelled by muscular action of the distended ventral pouch and tongue through the still exposed baleen plates. Once the water is expelled, they swallow their prey.

When blue whales feed just a few meters below the surface, they often surface slowly, belly first, exposing the throat grooves of the ventral pouch, roll to breathe, and evacuate the water before diving to take their next mouthful. If the prey is close to the surface, blue whales lunge vigorously on their sides or lunge up vertically by projecting their cavernous lower jaws 4-6 m up through the surface. Although surface feeding has often been observed during the day, it is more usual for blue whales to dive to at least 100 m into layers of euphausiid concentrations during daylight hours and rise to feed near the surface in the evening, following the ascent of their prey in the water column. In the North Atlantic, blue whales feed on the krill species Meganyctiphanes norvegica, Thysanoessa raschii, T. inermis, and T. longicaudata; in the North Pacific, Euphau-sia pacifica, T. inermis, T. longipes, T. spinifera, and Nyctiphanes sijmplex. In Antarctic waters they prey on E. superba, E. cnjs-tallorophias, and E. vallentini.

When foraging or feeding at depth, blue whales will generally dive for 8-15 min; 20-min dives are not uncommon. The longest dive recorded was of 36 min; however, dives of more than 30 min are rare.

Blue whales generally swim at 3-6 km when feeding. When traveling, they can attain speeds of 5-30 km and when chased by boats, predators, or interacting with other blue whales, thev can reach upward of 35 km.

B. Vocalization

Blue whales vocalize regularly throughout the year with peaks from midsummer into winter months. The majority of blue whale vocalizations are low frequency or infrasonic sounds of 17 to 20 Hz, lower than humans can detect. Blue whale sounds, at 188 decibels (louder than a jumbo jet at full power a few meters awav), are one of the loudest and lowest made by any animal.

These calls can be heard easily for hundreds of kilometers, thousands of kilometers under optimal oceanographic conditions and may cover whole ocean basins. The low frequencies produced by blue whales are ideal for communication between individuals of a widely dispersed and nomadic species through water without much loss of information.

IV. Reproduction and Longevity

Blue whales reach sexual maturity at 5-15 years of age; however, 8-10 years appear to be more usual for both sexes. Length at sexual maturity in females from the Northern Hemisphere is 21-23 m and is 23-24 m in the Southern Hemisphere. Males reach sexual maturity at 20-21 m in the Northern Hemisphere and at 22 m in the Southern Hemisphere (Yochem and Leather-wood, 1985). Mating takes place starting in late fall and continues throughout the winter. Female blue whales give birth every 2-3 years in winter after a 10- to 12-month gestation period. The calves, which weight 2-3 tons and measure 6-7 m long at birth, are weaned when approximately 16 m long at 6-8 months. No specific breeding ground has been discovered for blue whales in any ocean, although mothers and calves are sighted regularly in the Gulf of California, Mexico, in late winter and spring. A portion of the northeast Pacific Ocean blue whale stock could be using this region as a breeding ground.

Little is known of their mating behavior; however, female/male blue whale pairings have been noted with regularity in the St. Lawrence from summer into fall, some lasting for as long as 3 weeks. When a female/male pair is approached by a third blue whale, even a fin whale, vigorous surface displays, where all three animals can be seen racing high out of the water, almost breaching, porpoising forward causing an explosive splash of a bow wave, can result. Such interactions between blue whales usually last for 5-15 min.

Blue whales are thought to live for at least 80-90 years and probably longer. What is certain, however, after extensive photo-identification fieldwork on known individuals in the St. Lawrence and northeast Pacific, is that they live for at least 31 years.

V. Mortality

Documentation of natural mortality in blue whales is rare. The blue whale’s principal predator is the killer whale Orcinus orca, but there is little evidence of attacks on blue whales in the North Atlantic or Southern Hemisphere. However, in the Gulf of California, Mexico, 25% of the blue whales photo-identified carry rake-like killer whale teeth scars on their tails, indicating that attacks occur with some regularity but are probably rarely successful.

In the St. Lawrence, ice entrapment, where animals have been crushed, stranded, or suffocated by current and wind-driven ice floes in the late winter/early spring, has been reported.

While reports of blue whales approaching vessels are rare, at least 25% of the blue whales photo identified in the St. Lawrence carry scars that can be attributed to collisions with shipping. This type of scarring has been reported for a few northeast Pacific blue whales as well. Ship strikes in heavy shipping areas, such as the St. Lawrence and California coast, may have an impact on populations, but data are not available on this point.

Few entanglements in fishing gear have been reported, and it is thought that the size of the blue whale enables it to tear through fishing gear relatively unscathed.

Persistent contaminants accumulated over time, such as PCBs commonly found in blue whales from eastern Canadian waters, may have an impact on reproduction and limit the recovery of certain populations.

It has been shown that blue whales react strongly to approaching vessels. The degree of reaction depends on the whales behavior, as well as the distance, speed, and direction of the vessel at the time of approach. The increasing anthropogenic noise probably has an impact on blue whales and their habitat and could also limit recovery of this species.