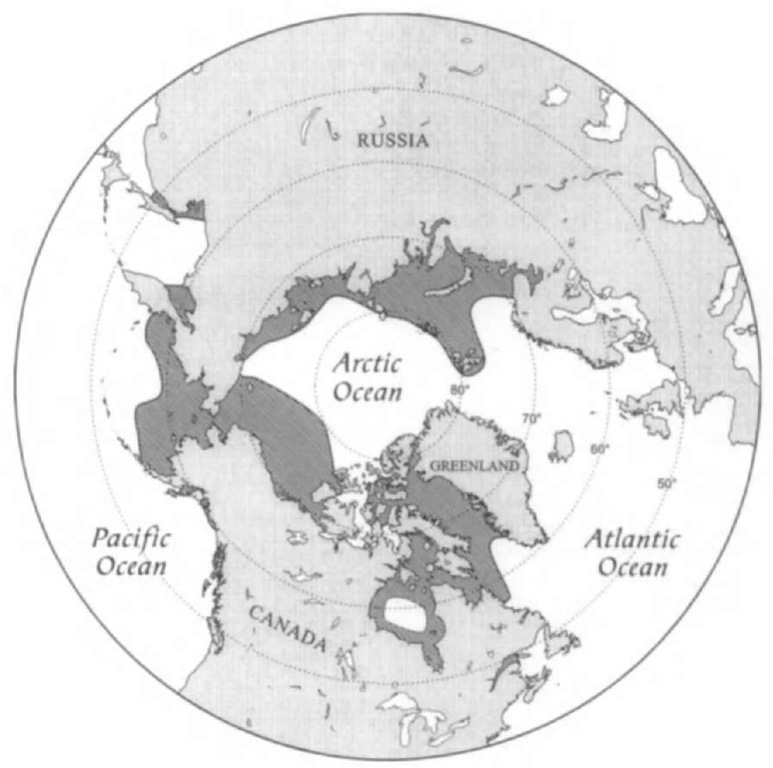

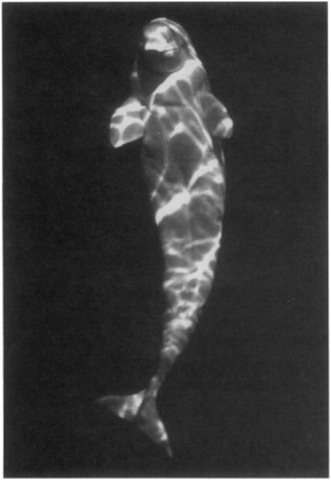

The beluga or white whale inhabits the cold waters of the Arctic and sub-Arctic (Fig. 1). Its name, a derivation of the Russian “beloye.” meaning “white,” appropriately enough captures its most distinctive feature, the pure white color of adults (Fig. 2). The evolutionary history and ecology of belugas are inextricably linked to the extreme seasonal contrasts of the north and the dynamic nature of the sea ice. As well as adaptation to the cold, life in this region has necessitated the evolution of discrete calving and possibly mating seasons, annual migrations, and a unique feature distinguishing it from most other cetaceans, an annual molt.

Figure 1 Worldwide distribution of the beluga whale. The northern most extent of its known range is off Alaska and northwest Canada and off Ellesmere Island, West Greenland, and Svalbard (above 80°N). The southern limit of distribution is in the St. Lawrence River in eastern Canada (47° to 49°N).

I. Taxonomy and Evolutionary History

The beluga whale is a member of the Monodontidae, the taxonomic family it shares with the narwhal, Monodon monoc-eros. The Irrawaddy dolphin, Orcaella brevirostris, was at one point considered by some to also be a member of this family. Although superficially similar to the beluga, recent genetic evidence strongly supports its position as a member of the family Delphinidae (Lint et al, 1990; LeDuc et al., 1999). The earliest fossil record of the monodontids is of an extinct beluga Denebola brachycephala from late Miocene deposits in Baja California, Mexico, and indicate that this family once occupied temperate ecozones (Barnes, 1984). Fossils of D. leucas found in Pleistocene clays in northeastern North America reflect successive range expansions and contractions of this species associated with glacial maxima and minima.

II. Description and Life History

The beluga whale is a medium-sized toothed whale, 3.5-5.5 m in length and weighing up to 1500 kg. Males are up to 25% longer than females and have a more robust build. As their genus name (“apterus’-without a fin) implies, they lack a dorsal fin and are unusual among cetaceans in having unfused cervical vertebrae, allowing lateral flexibility of the head and neck. They possess a maximum of 40 homodont teeth, which become worn with age, and may live to 40 years of age, possibly longer. Neonates are about 1.6 m in length and are bom a gray-cream color that quickly turns to a dark brown or blue-gray. They become progressively lighter as they grow, changing to gray, light gray, and finally becoming the distinctive pure white by age 7 in females and 9 in males (Fig. 3).

Belugas are supremely adapted to life in cold waters. They possess a thick insulating layer of blubber up to 15 cm thick beneath their slan, and their head, tail, and flippers are relatively small. The absence of a dorsal fin is believed by some to be an adaptation to life in the ice or perhaps as a means to reduce heat loss. In its place, belugas possess a prominent dorsal ridge that is used to break through thin sea ice.

Females become sexually mature at age 5, males at age 8, although males may not become socially mature until some time later. Gestation is 14-14.5 months with a single calf born in late spring-early summer prior to, or coincident upon, entry into warm coastal waters. Mothers produce milk of high caloric content and nurse their young for up to 2 years; the entire reproductive interval averaging 3 years. Little is known about the mating behavior or mating season of beluga whales. Mating is believed to primarily occur in late winter-early spring, a period when most belugas are still on their wintering grounds or on spring migration. Mating behavior, however, has been observed at other times of the year and the question of whether they have delayed implantation is unresolved.

Figure 2 Beluga tohale, Delphinapterus leucas.

III. Behavior

In contrast to the frozen smile of the oceanic dolphins, the ability of belugas to alter the shape of their moudi and melon enables them to make an impressive array of facial expressions. The lateral flexibility of the head and neck further enhances visual signaling and enable beluga whales to maneuver in very shallow waters (1-3 m deep) in pursuit of prey, to evade predators, and generally exploit a habitat rarely used by other cetaceans (see later).

Belugas typically swim in a slow rolling pattern and are rarely given to aerial displays. In nearshore concentration areas, however, such as Cunningham Inlet on Somerset Island in the Canadian High Arctic, belugas may engage in more demonstrative behaviors, including spy hopping, tail waving, and tail slapping (Fig. 4).

Figure 3 Beluga whales concentrating near the coast during the brief summer. Note the dark to light gray color of younger animals compared to the white of adults.

Recent findings from studies using satellite-linked transmitters attached to free-swimming whales have confirmed that belugas are capable of covering thousands of kilometers in just a few months, in open water and heavy pack ice alike, while swimming at a steady rate of 2.5-3.3 km/h (Suydam et al., 2001). Sensors on these transmitters have also recorded belugas regularly diving to depths of 300-600 m to the sea floor. In the deep waters beyond the continental shelf, belugas may dive in excess of 1000 m, where the pressure is 100 times diat at the surface, and remain submerged for up to 25 min (Richard et al, 1997; Martin et al, 1998)!

Figure 4 Aggregation of beluga whales interacting and rubbing on the substrate of a shallow estuary during the summer molt.

In areas of open water beluga whales may divide their days into regular feeding and resting bouts. Belugas appear to pre-dominandy hunt individually, even when within a group, but have also been observed to hunt cooperatively. A typical hunting sequence begins with slow directed movement combined with passive acoustic localization (search mode) followed by short bursts of speed and rapid changes of direction using echolocation for orientation and capture of prey (hunt mode) (Bel’kovich and Sh’ekotov, 1990).

IV. Acoustics-Vocalizations

The beluga possesses one of the most diverse vocal repertoires of any marine mammal and has long been called the “sea canary” by mariners awed by its myriad sounds reverberating through the hulls of ships. Communicative and emotive calls are broadly divided into whistles and pulsed calls and are typically made at frequencies from 0.1 to 12 kHz. As many as 50 call types have been recognized: “groans,” “whistles,” “buzzes,” “trills,” and “roars” to name but a few. Although some geographic variation is apparent, efforts to determine whether there are substantial regional differences or dialects have been hampered by differences among bioacousticians in the categorization of vocalizations. Belugas are capable of producing individually distinctive calls to maintain contact between close kin and can conduct individual exchanges of acoustic signals, or dialogues, over some distance (Bel’kovich and Sh’ekotov, 1990).

The echolocation system of the beluga whale is well adapted to the icy waters of the Arctic. Their ability to project and receive signals off the surface and to detect targets in high levels of ambient noise and backscatter enable belugas to navigate through heavy pack ice, locate areas of ice-free water, and possibly even find air pockets under the ice (Turl, 1990).

V. Ecology

As the sea ice recedes in spring, belugas enter their summering grounds, often forming dense concentrations at discrete coastal locations, including river estuaries, shallow inlets, and bays (Fig. 3). Several explanations have been proposed as to why belugas return to these traditional summering areas. In some regions, sheltered coastal waters are wanner, which may aid in the care of neonates. The occupation of estuarine waters also coincides with the period of seasonal molt. Belugas have been observed to actively rub their body surface on nearshore substrates (Smith et al, 1992; Fig. 4), and the relatively warm, low-salinity coastal waters may provide conditions that facilitate molting of dead skin and epidermal regrowth (St. Aubin et al, 1990; Smith et al, 1994). Belugas feed on a wide variety of both invertebrate and vertebrate benthic and pelagic prey. In some parts of their range it is clear that belugas are feeding in nearshore waters on seasonally abundant anadromous and coastal fish such as salmon, Oncorhtjnchus spp., herring, Clupea harengus, capelin, Mallottis villosus, smelt, Osmerus mordax, and saffron cod, Eleginus gracilis (Kleinenberg et al, 1964; Sea man et al, 1982). The relative importance of these factors in determining coastal distribution patterns may vary among regions, depending on environmental and biological characteristics (Frost and Lowry, 1990). It is clear, however, that belugas exhibit some degree of dependence on specific coastal areas.

In many areas of the Arctic, belugas soon leave these coastal areas to range widely off shore. Satellite tracking has recorded belugas moving up to 1100 km from shore and penetrating 700 km into the dense polar cap where ice coverage exceeds 90% (Suydam et al, 2001). How these animals find breathing holes in this environment is still a mystery. Analysis of dive profiles suggests that beluga whales may combine the use of sound at depth to find cracks in the ice ceiling overhead. Diving data also indicate that belugas are probably feeding on deepwater benthic prey as well as ice-associated species closer to the surface (Martin et al, 1998).

Little is known about the distribution, ecology, or behavior of beluga whales in winter. In most regions, belugas are believed to migrate in the direction of the advancing polar ice front. However, in some areas, belugas may remain behind this front and overwinter in polynyas and ice leads. In the eastern Canadian Arctic some belugas overwinter in the North Water, a large area of open water in northern Baffin Bay (Finley and Renaud, 1980), whereas in the White, Barents, and Kara Seas, belugas occur year-round, remaining in polynyas in the deeper water during winter (Kleinenberg et al, 1964).

Killer whales, Oreinus orca, polar bears, Ursus maritimus, and humans prey upon beluga whales. Belugas sometimes become entrapped in the ice where large numbers may perish or be hunted intensively by humans.

VI. Social Organization

Belugas are sometimes seen singly, but more commonly occur in groups of 2-10 that may aggregate at times to form herds of several hundred to more than a thousand animals. Single animals are always large adults, whereas in mixed herds adult males may form separate pods of 6-20 individuals. Adult females form tight associations with newborns and sometimes a larger juvenile, presumably an older calf. These “triads” may join similar groupings to form large nursery groups. At certain times of the year, age and sex segregation may be more dramatic than at others with males migrating ahead of or feeding apart from females, young, and immatures. In general, group structure appears to be fluid, with individuals readily forming and breaking brief associations with other whales. Apart from cow-calf pairs, there appear to be few stable associations. However, considering the diverse vocal repertoire of beluga whales, including individual signature calls, their wide array of facial expressions, and the variety of interactive behaviors observed, as well as the numerous accounts of cooperative behavior, this species appears capable of forming complex societies where group members may not always be in close physical proximity to each other.

VII. Population Structure

Variation in body size across the species range has been taken as evidence of separate populations. The nonunifonn pattern of distribution and predictable return of belugas to specific coastal areas further suggests population structure and has led to the treatment of these summering groups as separate management stocks. Resightings of marked or tagged individuals, as well as differences in contaminant signatures and limited evidence of geographic variation in vocal repertoire, add support to the independent identification of a number of these stocks. Although all are valid to varying degrees, many of these methods used for stock identification have limitations due to incomplete knowledge on year-round distribution, movement patterns, breeding strategies, and social organization. They provide little or no information on rates of individual or genetic exchange, and although phenotypic differences are highly suggestive, they may not provide evidence of evolutionary uniqueness.

A number of recent molecular genetic studies examined variation within the mitochondrial genome and confirmed that whales tend to return to their natal areas year after year and that dispersal among many separate summering concentrations is limited, even in cases where there are few geographic barriers (O’Corry-Crowe et al, 1997; Brown Gladden et al., 1997). These molecular findings reveal that knowledge of migration routes and destinations appears to be passed from mother to offspring, generation after generation. Such cultural inheritance of information leads to the evolution of discrete subpop-ulations, among which there is little dispersal. It is possible that many of these subpopulations may overwinter in a common area and that a certain amount of interbreeding may occur at this time. Regardless of such potential gene flow, in situations where management is concerned with the degree of demographic connectivity among areas, demonstrating that few animals disperse among subpopulations is sufficient evidence to designate them as separate management stocks.

VIII. Interactions with Humans

Because of their predictable migration routes and return to coastal areas, beluga whales have long been an important and reliable resource for many coastal peoples throughout the Arctic and sub-Arctic. A prudent subsistence tradition continues in many areas. However, primarily because of past commercial harvest excesses, current levels of subsistence taken from a number of populations may not be sustainable. Increasing human activity in the beluga’s environment brings with it the threat of habitat destruction, disturbance, and pollution. In areas where there are large commercial fishing operations, belugas, particularly neonates, may be incidentally caught in gill nets. In a number of regions of the Arctic, beluga whales exhibit strong avoidance reactions to ship traffic, whereas in some coastal locations they appear to have developed a certain tolerance to boat traffic. The potential impacts of an emerging whale watching industry in more populated areas are as yet unknown. In some areas, belugas may also be victims of industrial pollution. A high incidence of various pathologies have been found in beluga whales in the St. Lawrence River in Canada and have been linked to high levels of heavy metals and organohalogens found in these whales. Some of these toxins may act by suppressing normal immune response, and there is concern that contaminants are adversely affecting population growth (Beland, 1996). Finally, there is concern over the possible downstream effects of hydroelectric dams on estuarine habitats and the environmental and health risks associated with oil and gas development and mining in the Arctic.

Beluga whales were one of the first cetaceans to be held in captivity when in 1861 a whale caught in the St. Lawrence River went on display at Barnum s Museum in New York. Today, beluga whales are one of the more common and popular marine mammals in oceanaria across North America, Europe, and Japan. The majority of these animals are wild caught, but successful breeding programs at a number of facilities are increasing the number of belugas born in captivity. Although the majority of beluga whales in captivity educate and entertain the public, a number of whales have been put to work by the navies of the United States and former Soviet Union.