Beaked whales belong to the odontocete family Ziphi-idae. They are medium-sized cetaceans, with adults ranging from 3 to 13 m. They are characterized by a reduced dentition, elongate rostrum, accentuated cranial vertex, and enlarged pterygoid sinuses. There are currently 20 recognized species in five genera. They are all pelagic, living in the open oceans and feeding on deep water squid and fish.

I. Classification

|

Family Ziphiidae |

|

|

Subfamily Ziphiinae |

|

|

Berardius armixii |

Amoux’s beaked whale |

|

Berardius bairdii |

Baird’s beaked whale |

|

Tasniacetus shepherdi |

Shepherd’s beaked whale |

|

Ziphius cavirostris |

Cuvier’s beaked whale |

|

Subfamily Hyperoodontinae |

|

|

Hyperoodon ampullatus |

Northern bottlenose whale |

|

Hyperoodon planifrons |

Southern bottlenose whale |

|

Indopacetus pacificus |

Longman s beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon bahainondi |

Bahamonde’s beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon bidens |

Sowerby’s beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon boivdoini |

Andrews beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon carlhubbsi |

Hubbs’ beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon densirostris |

Blainville’s beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon eitropaetts |

Gervais’ beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon ginkgodens |

Ginkgo-toothed beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon grayi |

Gray’s beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon hectori |

Hector’s beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon layardii |

Strap-toothed whale |

|

Mesoplodon mirus |

True’s beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon peruvianus |

Pygmy beaked whale |

|

Mesoplodon stejnegeri |

Stejneger’s beaked whale |

II. Common Names

The common name of the family, beaked whales, refers to their pronounced rostrum or beak. The rostrum of beaked whales is, admittedly, relatively shorter than in most dolphins but relatively longer than most “whales.” The origin of the English term “beaked whale” is a translation of the Norwegian nebhval, which means “whale with a beak.” It is an extremely old Norwegian word, the origin of which is long lost to histoiy.

Most beaked whales are encountered rarely enough that they do not have “common names” but rather “vernacular names.” There seems to be a tendency toward the feeling that the Latin names that are used in science are somehow confusing and scientists will have to coin vernacular names in the language that is used by the people.

The only beaked whales that were seen on a regular basis by fishermen (and whalers) were the northern bottlenose whale (Hyperoodon ampullatus) and Baird’s beaked whale (Berardius bairdii). The English name “bottlenose whale” was actually in common use, as were the Norwegian name nebhval or naebh-val and the Danish and German name dogling or their derivatives in other northern European languages.

The name tsuchikujira or just tsiichi is the Japanese common name for Baird’s beaked whale (Berardius bairdii).

III. Diagnostic Characters and Comments on Taxonomy

Living beaked whales are characterized externally by a pronounced rostrum (beak), which blends into a high forehead (or melon) without a break (Fig. 1); a pair of throat grooves; relatively small flippers with short digits and relatively long arm bones; a small triangular dorsal fin that is placed far back on the body; and lack of fluke notches. Internally they have a reduction in teeth; fusion of the bones of the rostrum and development of extremely dense rostral elements in males; expansion of the pterygoid air sinus and elimination of its lateral bony wall; and elevation of the bones associated with the nose into a bony protuberance called the vertex (Fig. 2).

It seems that the concept of the beaked whales as a separate group of cetaceans became common in the 1860s and 1870s, as Gray used the family Ziphiidae in his “Catalogue of Seals and Whales in the British Museum” (1866) as did Van Beneden and Gervais in their epic “Osteographie des Cetaces” (1868-1879).

IV. Notable Anatomy, Physiology, and Life History

Several similarities between beaked whales and sperm whales became evident early. Partly these were due to the retention of ancestral characters and partly due to similarities in ecology. Both groups of whales feed at considerable depth and are specialized to feed on squid.

Ziphiids in general have reduced their teeth to the point that teeth in the upper jaw are vestigial or absent and teeth in the lower jaw are reduced to one or two pairs that usually erupt only in adult males. The only exception to this is Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasniacetus shepherdi), which has a full dentition in both jaws.

A. Externally

The pronounced rostrum results from an anterior extension of the rostral and palatal elements of the skull, the maxilla, premaxilla and vomer, coupled with a lateral compression to form a beak. Normally these bones are moderately extended in cetaceans to form a pincer-like beak, and, in fact the relative length of the rostra of some of the other toothed whales, like the river dolphins, exceeds that of beaked whales.

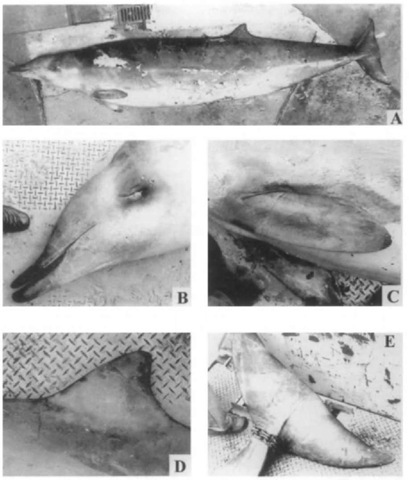

Figure 1 Details of the external morphology of an adult male Mesoplodon mirus (USNM 504612). (A) Lateral view of the whole animal, (B) lateral view of head, (C) lateral view of flipper, (D) lateral view of dorsal fin, (E) oblique ventral view of flukes.

Beaked whales have a high forehead, which sets off the long rostrum. This forehead is composed of the soft tissue that forms the facial apparatus and the elevated cranium on which it rests. This soft tissue is responsible for sealing the nasal passages against water and modifying the emitted sound. The blowhole is crescent shaped with the horns pointing anteriorly, except in the genus Berardius where they point posteriorly.

The forehead merges with the rostrum without a break or groove that is characteristic of most other toothed whales. There is only one dolphin (rough-toothed dolphin, Steno breda-nensis) that shares this character (Fig. IB).

Beaked whales have a pair of throat grooves, which are in the shape of a “v” with its apex pointing forward. The anterior end of the throat grooves lies posterior to the symphysis of the lower jaws and anterior to die jaw joint (i.e., in the throat region). Throat grooves are present in gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) and sperm whales (Fhyseter macrocephalus) but absent in all other species. They are not to be confused with ventral grooves, which stretch from the tip of the jaw back to the umbilicus in rorquals (Balaenopteridae).

Beaked whales have relatively small flippers, which are un-specialized. They consist of a relatively large forearm (radius and ulna) portion followed by a short phalangeal (finger) portion (Fig. 1C). This is also true of porpoises (Phocoenidae) and rorquals and appears to be a primitive cetacean character. Dolphins (Delphinidae) have an entirely different flipper shape, which tends to be falcate (hook shaped) and is the result of a lengthening of the phalangeal portion.

The dorsal fin is small and triangular instead of falcate and is situated on the posterior third of the body. The dorsal fin is usually placed over the anus at the junction of the abdomen and tail.

Figure 2 Skeleton of an adult male Mesoplodon densirostris in the Australian Museum, Sydney (after Van Beneden and Gervais, 1868-1879). Forelimb and pelvic rudiment are from an adult male of the same species in the American Museum of Natural History (after Raven, 1942).

The position of the dorsal fin in beaked whales correlates with a relatively long thorax and abdomen and short tail (Fig. ID).

Beaked whales normally do not have fluke notches, and the trailing edge of the flukes is unbroken. Embryologically, the fluke notch is formed when the trailing edge of the flukes moves back beyond the end of the caudal vertebrae. Caudal vertebrae anchor the midline of the trailing edge, resulting in a notch in other whales (Fig. IE).

B. Internally

The reduction in teeth has proceeded to the point where all functional teeth are lost in females and immature males, and dentition is only represented by a single pair of teeth in the lower jaw of males. Females and immature males have a pair of vestigial teeth. The dentition seems to be only useful in male aggression. The two exceptions to this are the whales of the genus Berardius, which have two pairs of mandibular teeth, and Tasmacetus, which has a normal odontocete dentition in both the upper and the lower jaws. In Tasmacetus, the apical pair of mandibular teeth is enlarged, which strengthens the hypothesis that the single pair of teeth in all other ziphiids represents the apical pair. A row of vestigial teeth is sometimes present in the gums of both the upper and the lower jaws of some beaked whales, particularly Mesoplodon grayi and Ziphius.

Rostral fusion in some males takes place with increasing age. Because age estimation in beaked whales has been difficult, we are not sure of the age in which this process is active. The mesorostral canal is filled in by dorsal expansion of the vomer and the individual rostral elements fuse together. This is accompanied by an increase in density of the rostrum. The density of the core of the rostrum has been measured at 2.4 g/cc in a male of Mesoplodon carlhubbsi and 2.6 g/cc in a male M. densirostris.

The pterygoid air sinus has become enlarged in the ziphiids. It still is confined to the pterygoid bone but has become relatively larger and lost its lateral wall. The anterior sinus is not developed in ziphiids.

The vertex of the skull has been expanded both laterally and vertically beyond the state in all other odontocetes. The vertex is composed of the posterodorsal ends of the maxilla and premaxilla, the nasals, and the medial ends of the frontals. The dorsal tip of the vertex has expanded laterally and anteriorly like a mushroom. This region is deeply involved with sound production and modification.

V. Fossil Record

Ziphiids first appeared in the fossil record in the early Miocene (de Muizon, 1991). These early ziphiids had long rostra, full dentitions with the first mandibular tooth often hyper-trophied, an elevated synvertex with a premaxillary crest, strong development of the pterygoid sinus with a reduction of the lateral wall of the pterygoid and an increase in the hamular process, and an auditory region of the skull that had minimal fenestration.

By the middle Miocene ziphiids were abundant. This was a period of maximum diversity of the entire order Cetacea and certainly was for the ziphiids. However, with all of this diversity, the origin of the modern genera is still in doubt.

There are about 14 genera of fossils currently recognized as ziphiids. Of these 14 genera there are at least 28 species that are based solely on rostral fragments. Critical work has demonstrated that 2 genera are based on nondiagnostic fragments and have been regarded as nomina dubia. With further study, particularly of the genera that are based on rostral fragments, there is bound to be a lot of demonstrated synonymy.

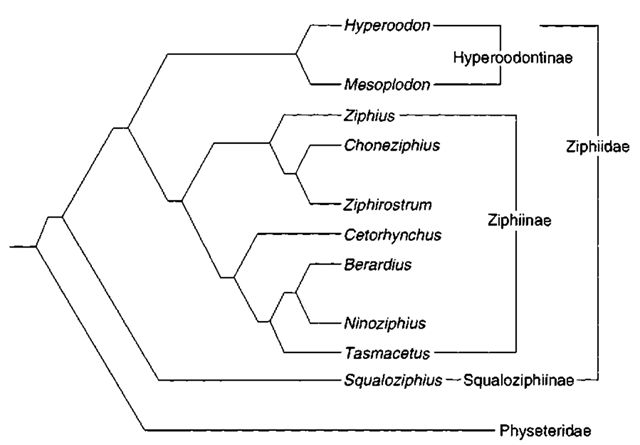

Muizon (1991) classified the Ziphiidae into three subfamilies: the Hyperoodontinae, which contains Hyperoodon and Mesoplodon; and Ziphiinae, which contains Ziphius, Berardius, Tasmacetus, and the fossil genera Choneziphius, Ziphirostmm, Cetorhynchus, and Ninoziphius: and the Squaloziphiinae, which currently contains only Squaloziphius. Figure 3 shows a cladogram of Ziphiidae.

VI. Interactions with Humans

Because of their pelagic habits and general lack of concentrated populations, ziphiids have not had much contact with humans. The only fisheries that had ziphiids as a target species were the bottlenose whale fishery in the North Atlantic and the Berardius fishery in the North Pacific.

The bottlenose whale was hunted from the middle of the 19th century by Norwegian and British whalers. Because the catches of the bottlenose whale were part of a multispecies small whale fishery, where catches of one species may serve to subsidize catches of another when the population of the second species has fallen to such a point that fishing of it would not be economical, the population was overexploited and became protected by the International Whaling Commission in the late 1970s.

Figure 3 Cladogram of Ziphiidae (after de Muizon, 1991). Indopacetus is included in Mesoplodon.

Berardius is hunted primarily by the Japanese, who have fished it out of shore stations on the northeast coast of Japan since at least the 17th century. It was taken incidentally by other nations in the process of whaling for other species. Because the Japanese market was local to the whaling stations and would consume other species of ziphiids, they formerly sometimes took Ziphius cavirostris and the occasional Mesoplodon.

In the Southern Hemisphere, whalers rarely took the southern forms of Berardius (B. arnuxii) and Hyperoodon (H. plan-ifrons). There were no fisheries based on them as the target species.

Ziphiids are moderately large, difficult to find and catch, and have habits (deep diving) that do not suit them to captivity. The occasional live strandings are sometimes maintained in captivity in hopes of rehabilitating them and learning something of their behavior. The rehabilitation attempts have never been successful and the animals always died. One Mesoplodon calf that stranded in California in 1989 lived 25 days in an aquarium.