There is a popular tendency to speak in rather nebulous terms about arctic marine mammals without defining the Arctic, the role and diversity of sea ice as a major component in high-latitude ecosvstems. or the diversity of marine mammals adapted to live in various ice-dominated habitats. There are. in fact, few truly arctic marine mammals. This introductory discussion is about those that occur in ice-covered seas, at least during winter and spring, and in most cases give birth when ice is present. They include one ursid, eight pinnipeds, and three cetaceans. Only three species have a continuous cir-cumpolar distribution. A few species (or stocks thereof) maintain a mostly year-round association with sea ice whereas most do not. The different marine mammals show various degrees of adaptation to ice. There is a continuum of ice-influenced habitats, and of mammalian adaptations to those habitats.

I. Northern Ice-Covered Marine Environments

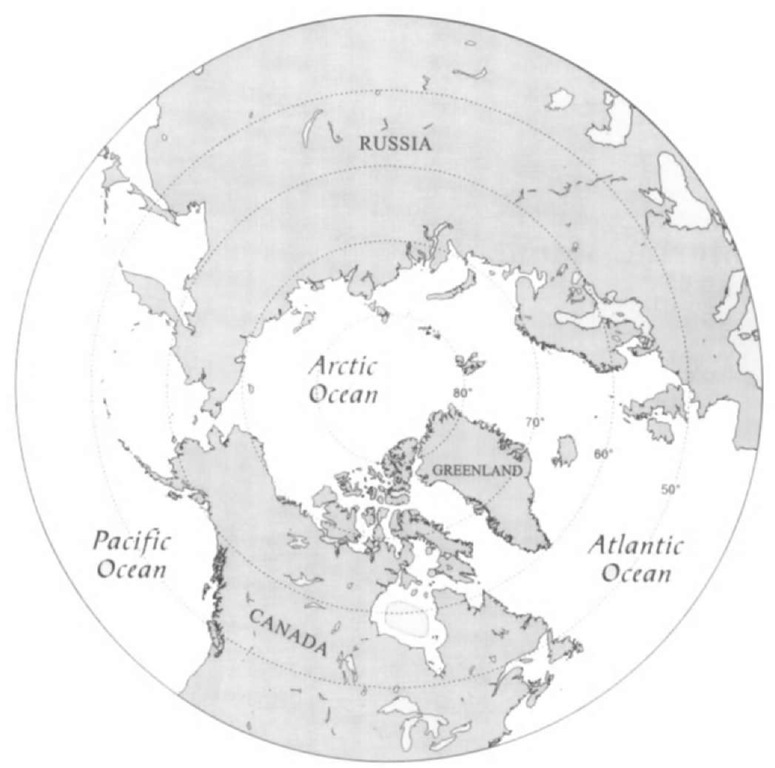

Traditionally the Arctic is viewed as an ill-defined region around the North Pole that is further subdivided into the high arctic and the low arctic. We are here concerned with much broader, although still poorly defined, areas within which ice-associated bears, pinnipeds, and cetaceans occur. Some freshwater seals are included. It is useful to think in terms of regional climate, oceanography, annual ice dynamics, and life history strategies. For most marine environments the definitions advanced by Dunbar (1953) are particularly useful. The arctic seas are those in which unmixed polar water from the upper layers of the Arctic Ocean occurs in the upper 200-300 m. A large portion of this zone is ice covered throughout the year. The maritime subarctic includes those seas contiguous with the Arctic Ocean in which the upper water layers are of mixed polar and nonpolar origin. There are, however, some noncontiguous subarctic seas (no water of polar origin) adjacent to terrestrial ecosystems that lie in the subarctic zone. Examples include the Okhotsk Sea. the northern part of the Sea of Japan (Tartar Strait), Lake Baikal in Siberia, and Cook Inlet in Alaska (Fig. 1). In the subarctic there is a complete annual ice cycle, from formation in autumn to disappearance in summer. Finally, there are areas in the temperate zone where unique climate conditions produce a winter ice cover of relatively short duration.

Such areas include the Baltic Sea, the northern Yellow Sea, and the western Sea of Japan.

In late summer the average annual minimum extent of sea ice is 5.2 million km2, restricted mainly to the Arctic Ocean. The average maximum extent in late winter-early spring is 11.7 million km2, including all of the subarctic seas (or parts thereof), and parts of some in the temperate zone. Most species of the so-called arctic marine mammals are associated with the seasonal ice during the breeding period. They cope with the annual expansion and contraction of the ice cover in a variety of different species-specific ways. Clearly there are many kinds of ice-dominated habitats formed in response to factors such as regional climate, weather, latitude, currents, tides, winds, land masses, proximity of open seas, and others.

II. Sea Ice Habitats

Sea ice in the Arctic and subarctic occurs in more complex forms than ice in the Antarctic. This is because of the central location of the Arctic Ocean with its perennial drifting ice, its partially landlocked nature, and the complexity of the subarctic seas encircling it. The annual expansion and contraction of the ice cover provides conditions ranging from the thick and relatively stable multiyear ice of the high latitudes to the transient and highly labile southern pack ice margins that border the open sea. Marine mammals must have regular access to air above the ice, as well as to their food in the ocean below it. During the breeding season the ice on which pinnipeds haul out must be thick enough and persist long enough for completion of the critical stages of birth, nurture of their voung, and, in many cases, completion of the annual molt. Additionally, by virtue of location, behavior, reproductive strategies, and/or physical capabilities, they must be able to avoid excessive pre-dation on dependent and often nonaquatic young. All of the marine mammals must also cope with the great reduction or complete absence of ice during the open water seasons.

There are many different features of the varied types of ice cover that provide marine mammals access to air and allow the pinnipeds to haul out. There are also some features, characteristics, or types of ice that exclude most marine mammals. Important ice features or types include stable land-fast ice (excludes most marine mammals): annually recurring persistent polynyas (irregular shaped areas of open water surrounded by ice); recurrent stress and strain cracks, coastal, and offshore lead systems (long linear openings); zones of convergence and compaction (as against windward shores or in constrictions such as narrow straits); zones of divergence (where boundary constraints are eased); the generally labile pack ice of the more southerly seas; and the margins of front zones of broken ice, the characteristics of which are strongly influenced by the open sea. Ice margins are particularly productive in that ice-edge blooms of phytoplankton and the associated consumers extend many tens of kilometers away from them,

III. Role of Sea Ice

There are great differences in how marine mammals exploit ice-dominated environments (Fig. 2). Many are a function of evolutionary constraints imposed on the different linages of mammals. Polar bears (Ursus maritimus) are the most recent arrivals in the high-latitude northern seas, having evolved directly from brown bears (U. arctos). They utilize relatively stable ice as a sort of terra infirrna on which to roam, hunt, den, and rest. Like their contemporary terrestrial cousins, they are generally not faced with the problem of ice being a major barrier through which they must surface to breathe. Cetaceans are at the other extreme. They live their entire lives in the water and have limited (though differing) abilities to make breathing holes through ice and are therefore constrained to exist where natural openings or thin ice are present. Pinnipeds spend most of their time in the water, but they must haul out to bear their young. Most of them also haul out on ice to suckle their young, to molt, and to rest.

Figure 1 Map of the Arctic Ocean.

For cetaceans, obvious benefits are protection from predators, access to ice-associated prey without competition from other animals, and a less turbulent winter environment shielded from perpetual and often storm force winds.

Pinnipeds have flourished in ice-dominated seas both in terms of the number of different species and in the number of individuals. All are obliged to haul out either on land or on ice for at least part of the year. As noted by Fay (1974), ice has several special advantages over land, including isolation from many predators and other disturbing terrestrial animals; vastly increased space away from seashores; a variety of different habitats that accommodate more species than does land; easy access to their food supply, especially for those that are benthic feeders or that utilize concentrations of prey associated with ice fronts and polynyas; passive transportation to new feeding areas and during migrations; sanitation resulting from the ability to avoid or reduce crowding and to haul out on clean ice; and shelter among pressure ridges or in snow drifts.

IV. Ice-Breeding Marine Mammals

Ice-breeding marine mammals in the Northern Hemisphere include eight pinnipeds: gray (Halichoems gnjpus) (some populations), harp (Pagophilus groenlandicus), hooded (Cystophora cristata), bearded (Erignathus barbatus), ringed (Pusa hisp-ida), spotted (Phora largha), and ribbon seals (Histriophora fasciata) as well as the walrus (Odobenus rosmarus); three cetaceans: narwhal (Monodon monoceros), beluga (or bulukha) (Delphinapterus leucas), and bowhead whale (Balaena inys-ticetus); and one fissiped: the polar bear

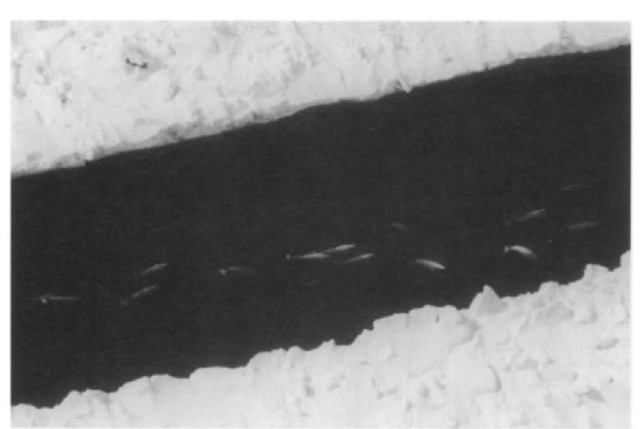

Figure 2 Distribution of sea ice influences the distribution of many marine mammals. In the winter, thickening ice can threaten the survival of individuals if they become trapped in areas away from open sea. In the spring and summer, pack ice fragments provide avenues of transit for whales, such as the beluga whales pictured. .

A. Pinnipeds

A common theme in the ecology of ice-breeding pinnipeds is that of an obligatory, or nearly obligatory, association with ice during the breeding season, which occurs during or shortly after the period of maximal ice extent and relative stability. Seal pups become independent during the spring onset of ice disintegration and retreat. Most species also molt on the ice, after which they disperse to a variety of habitats during the open water season, a few continuing to remain with the diminishing cover. They resume their increasing association with ice during autumn, as it again forms and expands. They haul out on the ice in all seasons during which it is present, although with highly variable frequency depending on species and weather. The maximum number of species and the greatest total number of seals are associated with ice when it is most extensive, and vice versa.

The lanugo of most seals born on ice or in snow lairs, and remaining in one place for long periods of time, is primarily an adaptation for maintaining body heat. Such pups tend to be small, have little insulating blubber, and have a relatively large surface area to body mass ratio at birth. White-coated pups presumably also benefit from the cryptic coloration it provides during the period before they are weaned and begin to enter the water. Prenatal molting occurs in those ice-breeding pinnipeds that are relatively large at birth and can enter the water within hours or days. Detailed discussions of northern ice-breeding seals are presented in the following species accounts, although genera] comments are noted below.

Gray seals are usually not included in the category ice-associated marine mammals. However, some populations breed on the ice. Gray seals largely inhabit the temperate zone in the North Atlantic region. Their distribution is coastal, often in association with harbor seals (Phoca vitulina). There are three populations: those in the Baltic Sea, the eastern North Atlantic, and the western North Atlantic. There is a very wide range in timing of the breeding season. In the eastern Atlantic, pups are born on shore during late autumn to early winter. In both the Baltic and the western Atlantic, however, pups are bom during mid- to late winter on ice near shore, or on shore when ice is absent. At birth, gray seals weigh about 15 kg. In all populations almost all pups are born with a silky, whitish coat of lanugo that is retained during the nursing period. They remain on ice or land until after weaning. The late pupping season of the marginally ice-associated breeding populations is thought to be an adaptation to that environment. Gray seals move extensively, although they are not considered to be migratory. None are associated with sea ice during late spring through autumn.

Spotted seals (or larga seals) occur in continental shelf waters of the Pacific region that are seasonally ice covered. During winter and spring they mainly inhabit the temperate/subarctic boundary areas, occurring in the southern ice front (mainly) of the Bering and Okhotsk seas or in the very loose pack ice of the northern Yellow Sea and Sea of Japan. The birth season is from January through April, depending on latitude. All populations give birth and nurture their pups on the ice. Newborn pups weigh about 10 kg and have a dense, whitish, wooly lanugo, which is shed toward the end of the month-long nursing period. Seals older than pups usually haul out on the ice to molt, although they also use land when the ice disappears early. As the seasonal ice disintegrates and recedes, all spotted seals disperse, moving to the ice free coastal zone where they use haulouts on land. The seasonal dispersal can be extensive: in the Okhotsk Sea to its entire perimeter and from the central Bering Sea to most of its perimeter, as well as northward into the northern Chukchi and Beaufort seas. Therefore, some spotted seals reside in the higher latitudes of the subarctic zone during the open water season. They range widely over the continental shelves. There is a close association with sea ice during autumn through spring.

Ribbon seals are animals of the temperate and temperate/subarctic boundary zones in the North Pacific region. Breeding populations are in the Bering and Okhotsk seas and Tartar Strait. During the open water season they live a completely pelagic existence in the cold temperate waters along and beyond the continental shelves, often far from the locations of their winter habitat. The breeding cycle is similar to that of the spotted seal, and the two occur in relative close proximity to each other during late winter and spring. At the time of pupping and molting, ribbon seals utilize ice of the inner ice front where floes are larger, thicker, more deformed, and more snow covered than in the adjacent ice margin favored by spotted seals. They are noted for hauling out on very clean ice. They pup in late March and April. At birth the pups weigh about 10.5 kg and have a coat of dense, white lanugo. During the nursing period the pups remain on the ice and gradually shed their lanugo. They remain on the ice for some time after they are weaned. In the opinion of this writer the preference for heavier ice of the inner front, which persists longer than that of the spring ice margin, is because it permits all age classes of these otherwise pelagic seals to haul out until the molt is completed. Ribbon seals do not come ashore unless debilitated. They appear to be the pinniped analogue of the Dalls porpoise (Phocoenoides dalli) during the pelagic phase of their annual cycle (June through late autumn), dispersing near the shelf breaks and the deeper waters beyond. They have the morphological and physiological attributes of a seal that can dive to great depths and remain submerged for a long time. Relatively few move north of their breeding range, except during years of minimal spring ice cover.

Harp seals occur in the North Atlantic region. There are three breeding populations: those of the White Sea, the Greenland Sea, and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. They are a gregarious and highly migratory species that lives primarily in the subarctic zone during winter and spring and is broadly distributed in the open sea from the coastal zone to near the ice margin during the open water season. The birth period extends from late January to early April, depending on the region. During the pupping season they form large aggregations in which pups are born in close proximity to each other (often closer than 2.5 m). They prefer large ice fields within the ice front, usually at some distance from the pack ice margins. Here the floes are extensively deformed and ridged, providing shelter to the otherwise exposed pups. At birth the pups weigh about 11.8 kg and have a coat of dense white lanugo. The nursing period lasts from 10 to 12 days and they fast, remaining on the ice floes, for some time after weaning. Mating, which occurs after pups are weaned, is followed by the molt. As with the ribbon seal (which is also pelagic after the molt) it seems that the preference of harp seals for the thicker and more stable ice of the inner front zone is because it provides the selective advantage of persisting until the molt is completed. Harp seals make one of the longest annual migrations of any pinniped, with some traveling more than 3000 miles from wintering to summering areas. Part of the spring migration is passive as the seals drift on the receding ice.

Hooded seals are a high subarctic, strongly migratory, deep water species that occurs in the North Atlantic region and whelps in four different areas: near Jan Mayen, in Davis Strait, off the Labrador coast, and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Shifts to heavier ice in the more northerly whelping areas reportedly occur during periods of warmer climate and diminished ice (drift ice pulsations). Pups are mainly born on thick heavily ridged ice floes well within the subarctic pack during late March and early April. At birth the pups weigh about 22 kg (relatively large) and are comparatively precocious. Their lanugo is shed in utero and their birth coat (the blue-back stage) does not resemble the pelage of adults. The nursing period is amazingly brief, averaging 4 days, during which the mothers remain on the ice with their pups. Pups enter the water shortly after weaning, although they spend considerable time on the ice during the postweaning fast. Mating occurs after lactation, and molting after mating. They migrate, both passively oil the ice and by swimming, and disperse widely in the open sea (to the Grand Banks), near high-latitude shores, and along the edge of the summer pack ice. Extralimital occurrences are common, even to the North Pacific region.

Bearded seals are primarily benthic feeders that have a cir-cumpolar distribution in arctic and subarctic seas. They have evolved in the face of heavy predation pressure by polar bears. Their range broadly overlaps that of all the other ice-breeding pinnipeds. They are the least selective of the seals with respect to ice type, provided that it generally overlies water less than about 200 m deep. Bearded seals are usually solitary and occur from the southern ice margins and fronts (few) to the heavy drifting pack around the rim of the arctic basin, although infrequently in landfast and multiyear ice. Within the heavier pack ice they occur mainly in association with those features that produce open water or thin ice (polynyas, persistent leads, flaw zones, etc.). They are capable of breaking holes in thin ice (slO cm) and can make or at least maintain breathing holes in thicker ice with their stout foreclaws. The large pups (about 34 kg) are usually born on the edges of small detached, first year floes very close to the water. The lanugo is shed in utero. The pups can swim from birth if necessary, and usually do so, at least in order to move away from the afterbirth. Beyond that they remain on the ice for a day or so. Nursing, which is usually on the ice, lasts 12 to 18 days, during which time the pups spend a considerable amount of time in the water and begin independent feeding prior to the end of the nursing period. Mating occurs after pups are weaned. The main period of molt is during May and June, and the greatest numbers of all age classes haul out on the ice during that time. However, molting seals are encountered throughout the year. In some areas, such as the Bering and Chukchi seas, the adults and most juveniles migrate to maintain a year-round association with ice. They haul out on it throughout the year, although infrequently during winter. In areas where ice disappears during summer (i.e., the Okhotsk Sea) or recedes beyond the continental shelf, they occur in the open sea, in nearshore areas, in bays and estuaries, and sometimes haul out on land.

Ringed seals have a circumpolar distribution that includes the arctic and subarctic seas. They have evolved in the face of heavy predation pressure, primarily by arctic foxes, which take pups, and polar bears, which take all age classes. Unique species and subspecies of the genus Pusa also occur as landlocked populations in Eurasia and include the seals of lakes Baikal, Ladoga, and Saimaa. as well as the Caspian Sea. Ringed seals are the most numerous and widely distributed of the northern ice-associated pinnipeds. During winter to early summer they utilize all ice habitats from the drifting ice margins and fronts (relatively few) to thick stable shore-fast and multiyear ice. Their range extends farther north and includes areas of heavier ice cover than that of any other marine mammal except the polar bear. They occur from shallow coastal waters to the deeps of the Arctic Basin. During winter through late spring the adults tend to be solitary and territorial and are most abundant in moderate to heavy pack and shore-fast ice. Ringed seals can make and maintain holes through the ice and crawl out to construct snow lairs above them. In regions where conditions permit, they migrate and maintain a year-round association with ice. In some regions where the pack ice completely or mostly disappears during summer (i.e.. the Okhotsk Sea, Baffin Bay, Lake Baikal) they move to nearshore areas and sometimes haul out on land.

Pups are born during late March through April, in snow lairs or cavities in pressure ridges. The pups are small, averaging about 4 kg at birth, and have a thick woolly lanugo, which is usually shed by the end of the nursing period. Lactation lasts 4 to 6 weeks. Pups mostly remain in the birth lair for the first several days, but are soon capable of entering the water and periodically returning to a lair. Mating occurs after the nursing period and is followed by the molt. The peak period of molt in nonpups is during May and June, when the seals haul out above collapsed (melted) lairs, at enlarged breathing holes, or next to natural openings in the ice. Ringed seals are extremely wary when hauled out. During the open water season, depending on the region, they occur in the much reduced pack ice and in open water over a broad area. In some regions they haul out on land.

Walruses are the largest and most gregarious of the ice-breeding northern pinnipeds. They have a discontinuous although nearly circumpolar distribution around the perimeter of the Arctic Ocean and the contiguous subarctic seas. They are benthic feeders mainly restricted to foraging in waters less than 110 m deep. In all areas their distribution is limited by water depth and in some (i.e., the Laptev and Kara seas) it is further constrained by the severity of ice conditions. In most regions, walruses haul out on ice in preference to land. However, during the open water season, they (mainly males) use land haulouts near the wintering grounds and, in more northerly areas, most come ashore to rest when ice drifts beyond shallow water, as occurs frequently in the Chukchi Sea. During autumn, walruses that migrate southward ahead of the advancing ice also come ashore to rest. All populations are associated with seasonal pack ice during winter to spring/early summer. They mainly use moderately thick floes well into the winter/spring ice cover. The combined requirements for floes low enough to haul out on, but thick enough to support these large animals (usually herds of them) and that are also over shallow productive continental shelves, make walruses particularly dependent on regions within which persistent natural openings are present. They make (batter) holes through ice as thick as 22 cm, using the head, and sometimes maintain them with the aid of their tusks.

Calves are born mainly in early May. which for the Bering Sea population is during the northward spring migration of females, calves, subadults. and some adult males. Walruses shed their lanugo in utero. Calves are born on the ice. They weigh about 60 kg and enter the water from birth, although they haul out frequently. Cows with young calves often form large nursery herds and migrate passively on the drifting ice. as well as by swimming. The nursing period lasts more than a year. Walruses haul out in all months of the year.

B. Cetaceans

Ice-associated cetaceans include two odontocetes (toothed whales), the beluga and the narwhal, and one mysticete (baleen) whale, the bowhead. None have a completely circumpolar distribution. Morphological adaptations to ice seem minimal and include the lack of a dorsal fin in all three and the high “armored” promontory atop, which the blowhole of the bowhead is situated. In winter, all three species occur in drifting ice where there are persistent natural openings or where the ice cover is thin. Polynyas. shear zones, and leads are important features for them in regions of heavy pack ice.

The narwhal is a North Atlantic species of the high subarctic and low arctic, which, in winter, consistently occurs in regions of heavy drifting ice over deep water or shelf edges. Adult males have a unique, long unicorn-like tusk that has an unknown function but is presumably used in male sexual display. The largest population is that in Davis Strait and Baffin Bay. Seasonal movements of narwhals are directly tied to the advance and retreat of ice. During summer they move to high-latitude, ice-free coastal and nearshore areas, which are often penetrated by deep fjords. Calves are born during the summer, reportedly during July and August, and are nursed for more than a year. This whales’ preference for heavy pack ice during winter and spring makes them particularly vulnerable to entrapment during periods of rapid ice formation or when the pack becomes tightly compressed. Most episodes of entrapment are probably brief, although prolonged confinement and rapid ice formation sometimes result in death either by drowning or by polar bears, for which entrapped whales are easy and plentiful prey. Confined whales are also harvested by Inuit hunters whenever they are found.

Beluga whales have a nearly circumpolar distribution that extends from roughly 40°N (the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the northern Sea of Japan) into the summer multiyear pack of the Arctic Ocean. During winter they are most abundant near the southern ice margins and fronts and as far into the seasonal pack as conditions permit. Again, polynyas. flaw zones, persistent leads, and other features that permit belugas to surface for air are important in the more northerly regions. Belugas often make holes through thin (to about 10 cm) newly formed ice by pushing it up with their head and back. They also surface in openings made by bowheads. with which they often associate during spring migration.

Distribution during the open water season is quite variable depending on region. In most cases these whales move into the coastal zone in May to July or early August, where they enter lagoons and estuaries to feed, bear calves in wanner water, and molt. They frequently ascend rivers to feed on seasonally abundant fishes. Telemetry studies have shown that belugas in the Beaufort Sea and the Canadian high arctic spend slightly less than 2 weeks in lagoons, and spend most of their summer feeding in offshore waters (unlike belukhas farther south). Some males from the eastern Chukchi and Beaufort Sea stocks are now known to penetrate much farther into the pack ice of the Arctic Ocean during summer than was previously supposed (to beyond 80°N). Other belugas range widely throughout Amundsen Gulf and the Beaufort and northern Chukchi seas during summer and early autumn.

The Bering Sea population includes multiple stocks, some of which migrate north through the disintegrating ice cover in spring and use both ice-free coastal waters and the summer pack of the Arctic Ocean. Most belugas leave the coastal zone by September, although some remain or revisit areas where food is abundant. This habit has resulted in some large and fatal en-trapments. Smaller entrapments at sea are not uncommon. All move with the advancing ice in autumn, either migrating soudiward with it or moving into it as it forms and expands.

Bowhead whales occur in subarctic waters during winter and spring and, depending on the population, in productive marginal arctic waters during the open water season. These large whales are highly specialized zooplankton feeders and seek areas of high prey abundance. Bowheads may be the slowest growing and latest maturing mammal on earth. Females are thought to become sexually mature between their late teens to midtwenties (later than humans or elephants). They may live to be well over 100 years old.

The range of bowheads includes the North Atlantic region (three stocks) and North Pacific region (two stocks), with extensive gaps between the two. During winter through early spring they occur from the southern margins of the ice pack to as far into it as persistent natural opening in the ice permit. Large polynya systems are of great importance during winter and spring. In the Pacific sector the Okhotsk Sea stock remains there after the ice has completely disappeared. Most whales of the other stocks migrate northward during spring and southward during autumn. Most whales of the Bering Sea stock maintain a loose association with the summer ice margin, mainly feeding in the open waters south of it. The northward migration begins in late March or early April when they move from the Bering Sea into the eastern Chukchi, and then the Beaufort seas through heavy ice in a very long corridor cleaved by a linear system of stress cracks, polynyas, shore leads, and flaw zones. Some migrate into the western Chukchi Sea. Beluga whales commonly migrate with bowheads. Bowheads can stay submerged for long periods and push up through relatively thick ice. These abilities allow them to reside and travel in waters where natural openings in the ice are continually forming and refreezing. Calves are born mainly during April to early June, during the spring migration.

C. Fissipeds

Two fissipeds roam the high-latitude ice-covered seas: the polar bear and the arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus). The latter, which rarely enters the water and pups in dens on shore, is not usually considered to be a marine mammal.

Polar bears have a circumpolar distribution in the Arctic and contiguous high subarctic. They are not “marine” in the sense that whales or seals are, but occupy a marine environment in which ice is the substrate on which they live. They prey on other marine mammals, particularly the ringed seal. Depending on the region, they remain with the ice and hunt year round or, where it completely disappears, they come ashore and usually fast. Exceptions to the latter are some islands (i.e., Wrangel and Herald) where they feed on beachcast carcasses or hunt animals that haulout on shore, particularly walruses. On the ice, the availability (access) of prey seems to be a more important factor affecting the distribution of bears then is maximum prey abundance. It is difficult for bears to catch marine mammals, except pups, when there are unlimited escape routes and places to surface in a very labile ice cover. For example, few polar bears range south of the northern Bering Sea during winter, even though the majority of other marine mammals (except ringed seals) are south of there. Also, polar bears are not present in the Okhotsk Sea.

Pregnant females make and enter snow dens in early November. These maternity dens can be on the heavy pack ice, on shore-fast ice (relatively few), or on land. The altricial cubs are born in late December or early January, during the arctic winter, and do not emerge with their mothers until late March or early April. Sows that bore their cubs on shore go immediately back to the sea ice. Ringed seal pups, born in lairs beneath the snow starting in late March, are important prey for sows with cubs.

V. Possible Effects of Climate Change

It is now well recognized that we are in a phase of accelerated global warming and that the inultiyear and seasonal ice cover is being affected. The seasonal ice cover is becoming generally less extensive and thinner, and it is forming later and disintegrating earlier than at any time in recorded history. In the Arctic Ocean the ice cover is also thinning. Similar changes have occurred in the past. In addition to a somewhat diminished ice cover, warming conditions also produce rising sea levels, increased ocean circulation, and increased nutrient flow into the northern seas. These changes are likely to have varying effects on the different species of ice-breeding marine mammals. For some species, e.g., the walrus, ringed seal, and polar bear, ameliorating conditions might be positive as they would result in more favorable habitat over a broader area then at present. For others, especially those now dependent on limited ice habitat, the changes are likely to have negative impacts. Spotted seals in the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan are likely to be affected negatively. At a minimum, global warming will likely result in geographic shifts of the seasonal centers of abundance of all ice-associated marine mammals.