Eros—the Greek word for love—and its human, cosmic, and divine power, remains one of the richest linguistic sources of speculation on this compelling theme in the history of religions. In the comparative study of religions, the theme of love has deep roots in early Greek literatures, in Hesiod and the tragedians, in Plato’s dialogues—particularly in the Symposium and Phaedrus—and in the discourses of the later Stoa. Early Greek discourses on the destinies and vicissitudes of eros are critical to the comparative discussion of love in the history of religions, from the Ancient Near East, western Asia, and the Mediterranean, to contemporary cultural studies in North America.

Greek sources speak of love’s deeply ambivalent but necessary powers. Eros is about division but also speaks of idealized unity. Deeply rooted in sexual passions, eros is dangerous, volatile, and identified with madness and transgressive ecstasies. It is also a source of idealization, nobility, and beauty; when it is properly channeled—love is ennobling to both lover and beloved—it is a source of the virtues of truth and beauty in themselves. But the question of how to channel this magnificent and threatening power remains an open question in early Greek speculation. The goals of eros are neither simple nor univocal. A potential source of virtue—when it is said to serve a ladder of ascent—eros never loses it power to divide, to fracture, to reassert duality, or to push the would-be climber back down the stairs of ideal virtues. Eros—as early as Hes-iod, where it is, after Chaos and Gaea (Earth), one of three primordial deities—is about melting and marrying; it is about unions and about generation, but also about ties woven so strong that they inspire violent jealousies, hatred, volatile vulnerabilities, and destabilizing asymmetries.

Plato, in the Phaedrus (251C) hints that himeros (desire), derives from mere (particles), ienai (go), and rhein (flow) when he describes the streams of particles that flow from the body of the beautiful boy and inundate the eyes of the beholding lover. In Cratylus (420A) of The Collected Dialogues of Plato (1987), himeros is linked with images of hrous (flow) and eres, from esren, (flowing in). Earlier, in 418 C-D, himeros is derived from himeirousi (to long for light in the darkness). Here Socrates works outward from the words for day, himera or emera. Daylight, visible luminosity, and flow: Eros is liquid light, like Leonardo’s visible currents of air.

Socrates’ famous speech in the Symposium that summarizes the doctrine of eros is attributed to the Mantinean wise woman Diotima, and would seem to successfully domesticate the native unruliness of eros. There, Socrates- Diotima charts an ordered, step-wise, goal-focused “ascent of eres,” from earthly to heavenly forms of love; from love of the individual person to the individual body; a love vulnerable to pain and attachment, to need and desire—to love of his/her qualities; love of beautiful objects or ideas (logous kalous: 210A); and finally, beyond, to a great sea of beauty and truth, a transcendental state that strips away all that is merely human in love (210A-211C). There is no longer a particular boy, a particular lovely body, but one is grounded in “the Beautiful itself, absolute, pure, unmixed, not polluted by human flesh or colors or any other great nonsense of mortality. . . .”

This is orthodox love, a love that always leads, in an orderly manner, the lover upward “for the sake of Beauty, starting out from beautiful things”—the particular body of a particular beloved—and “using them like rising stairs” (hosper epanabasmois chromenon: 211C). But as Martha Nussbaum has shown quite powerfully in her studies of the Symposium and Phaedrus, this is hardly Plato’s final word on eros. After the Diotima speech, Alcib-iades, Socrates’ young errant lover, bursts into the drinking party and systematically answers back every point made by Socrates in his speech: He argues vulnerability and instability to Socrates’ impassibility—his stony transcendence; he argues vivid particular material images (eidela of the Silenus statues: 215B) and concrete material beauty to Socrates’ shimmering invisible “true virtue” (de areten alethe: 212A); passions to irony, tormenting closeness to Socrates’ remote round gleaming; warmth to the cold impassible body; lack to sure possession; and “suddenness” to Socrates’ studied intellectual trances.

Plato reveals eros at the end of the Symposium in all its dividedness. On the one hand, this view of love is potentially ennobling and a process of ascent that transcends its roots in the love of an individual person; an individual body in its sexual particularity; to any beautiful body; to beautiful ideas; and to beauty and virtue itself. On the other hand, Plato makes a very powerful and concrete argument about the particularity of love that ruins and makes vulnerable; that makes one a slave, or mad; love that is irreducibly about another person, or the other who is impossible to encompass, transcend, or turn into a universal idea. As Socrates says of his fatal lover, “I shudder at his madness and passion for love” (213D).

Nussbaum argues that this dilemma, this tension at the heart of eros, is resolved by Plato in the Phaedrus, particularly in Socrates’ recantation speech and defense of mania—love’s vulnerability to the particular and to madness. Socrates has just listened to Phaedrus read to him a learned discourse on love by a certain Lysias, whom Phaedrus deeply admires, when the author recommends the young man avoid accepting the service of one who loves him, and seek out the one “who does not love.” After criticizing Lysias for his disingenuousness and arbitrariness, his lack of clear structure, and his mere rhetorical treatment of this important theme, Socrates responds, his head covered, with a speech that faults love for its powerful jealousies and its lovers whose loves ultimately do more harm than good to their beloved boys—in mind, body, possessions, family, and friends.

But after crossing the river, Socrates feels he has made offense; a daimonion, a “familiar divine sign,” comes to him like a voice on the air. He recants his previous condemnation of eros and proceeds to formulate quite another kind of approach—one that neither condemns eros nor subsumes it, as in his Diotima speech in the Symposium—into some higher experience beyond the passions. This speech will defend eros and its mania undiluted as being at the very heart of the life of virtue.

What is implied in this shift is that eros in its ascent ceases altogether to be eros as it gives up the particular, other person. The ladder of love is hardly a satisfactory answer to the real dilemmas of desire. Real eros, the particularity of its needs, passions, interests, limits, and vul-nerability—so critical to human flourishing (eudaimonia)—demands an encounter with the world of concrete risk, of luck, to truly love, and ultimately, to truly embark on the adventure of eudaimonia.

The destiny of this volatile dangerous word enters the Christian tradition in its first four centuries through the writings of Origen and Gregory of Nyssa. Although the Greek text of the Song of Songs uses agape and its various verbal transformations for love and for being in love (Septuagint 1979, 2:4; 7), Christian commentators like Origen and Gregory, writing in Greek, often associate agape’s actual pitch of meaning as equivalent to eres, a word that carries a semantic register of intense desire, uneasy union, inexplicable wounding, and unstable yearning. In Gregory’s commentaries on the Song of Songs, eres, and not the more generalized agape, best describes love of God as infinite insatiability, sharp yearning, at once painful and blissful, which leads one on the path to epektasis (eternal progress) into—and more radically in—God. At one point in his Canticle commentary, Gregory notes, “For heightened agape is called eres” (epitetamene gar agape eres legetai) (Gregorii Nysseni Can-ticum Canticorum, Oratio XIII, 5, 10 [1048C], 383).

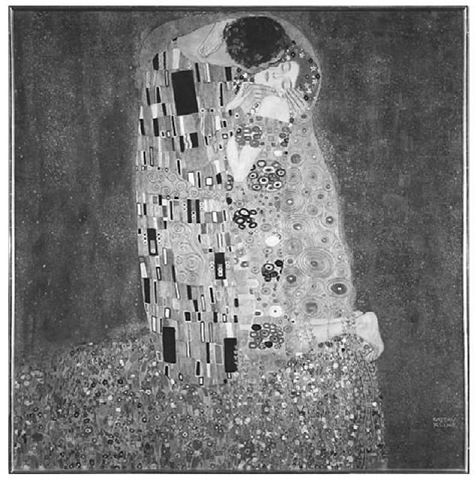

The Kiss by Gustav Klimt.

At the heart of erotic love in the Greek eros traditions lives a felt experience of difference, of irresolvable singularity, along with the most thoroughgoing visions of ideals and universal ennobling virtues. A source of loving bliss, of transcendental energies, eros also writes suffering and separation into the body.