The word ecstasy has Greek origins. Ekstasis literally means “standing outside oneself.” As a category in the study of mysticism, ecstasy has most often signified mystical union. By merging with a divine or supernatural other, the devotee in essence “stands outside” her or his own mundane self.

This notion of mystical union has also become the focus of studies such as those by Georges Bataille (1986) that interpret religious ecstasy more broadly as a manifestation of eroticism. But as “standing outside oneself,” ecstasy not only encompasses the fullness of union but also the emptiness of loss. It is this dynamic of loss and union that underlies portrayals of ecstasy within the world’s religious traditions.

Within the Judaic tradition, the visions of Isaiah and Ezekiel are often taken to be paradigmatic experiences of ecstasy. Isaiah was taken out of his position in time and space and saw the impending doom of Judah, whereas Ezekiel had a vision of God in the whirlwind. The experience of Ezekiel in particular served as an inspiration for the Merkabah tradition of Jewish mysticism that flourished in the first millennium of the Common Era. In one of the central Merkabah texts, the Pirkei Heikhalot, the ascent of the mystic to the throne of God culminates in ecstasy. Entering the seventh palace of heaven, the mystic confronts visions that lead him to collapse until he is supported by the heavenly hosts and led to behold the magnificence of God. This is an ecstasy brought about by God’s transcendent majesty. Abraham Abulafia, the thirteenth-century kabbalist, developed a system of mystical techniques by which to attain the mystical union of the soul with the divine. This genre of kabbalah, known also as prophetic kabbalah, employed melodies of the vocalized permutations of the letters of the holy names found in the Torah. The main goal of this technique of liturgical chanting was the attainment of ecstasy. Music, especially as accompanying ritual and prayer and understood for its theurgic power to bring about divine harmony, was also adopted by Safed kabbalists of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. An example of this trend is the composition of Sabbath hymns such as “Lekha Dodi” by Shlomo Alkabetz. Forms of Hasidic prayer and rituals can also be said to be motivated by the goal of attaining ecstasy.

In the Christian tradition, ecstasy has taken a number of forms. For Dionysus the Aero-pagite, ecstasy was understood in terms of the deification of the individual in union with God. For St. Francis de Sales, it was through immersion in love of neighbor that one moved beyond oneself toward contact with God. For Carmelite mystics, ecstasy was understood in terms of both absence and rapture. For St. John of the Cross, God came in the dark night of the soul of the person suffering from an internal emptiness that only faith prevented from developing into despair. St. Therese of Lisieux spoke of the ecstasy of contact with God—not only in terms of adoring the Lord by spreading flowers before his throne, but also in terms of being pierced by the “arrow of His love.” Experiences of ecstasy in the Catholic tradition often accompany claims of supernatural powers or attributes such as unnatural lightness and levitation, as in the case of St. Teresa of Avila, or of unnatural heaviness and bilocation, as in the cases of Rose Ferron and Audrey Santo— two New England women who were acclaimed for holiness in their own lifetimes.

Catholic claims of supernatural powers proceeding from ecstasy would find parallels in the Protestant Pentecostal tradition. Healing and prophecy are often associated with glosso-lalia, or speaking in tongues. Glossolalia is taken as a sign of the presence of the Holy Spirit, an ecstasy of possession in which the person loses a sense of self within the overwhelming presence of the divinity. Some commentators have likened this experience of ecstasy to the forceful ripping away of self. Dennis Covington (1996) described a small Pentecostal holiness sect that handled rattlesnakes and drank strychnine to prove their faith. Enraptured in glossolalia during their rituals, the ecstasy of the snake handlers in Cov-ington’s view, was a portrait in the painful “loss” of self.

Edward Said, in his influential Orientalism (1979), remarked how much of the most influential scholarship on Islam has focused on mysticism as the core of the Islamic tradition. Certainly such was the case for Annemarie Schimmel (1975), who described various states of mystical ecstasy in the Islamic tradition. Schimmel described the path of the Sufis, Muslim mystics who take their name from a woolen garment worn by ascetics. Traveling along this mystical path, the Sufi surrenders to God, embracing gratitude and patience. As the mystic moves toward God, he experiences several ecstatic states beginning with marifa— knowledge of the divine that purges or empties the heart of everything but God. Then there are the stages of fana and baqa, “annihilation of self-hood” and “subsistence in God,” respectively. Fundamental to Islamic understanding of ecstasy is absorption in the total transcendent agency of God.

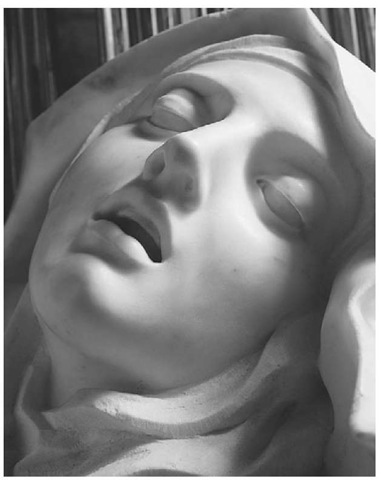

Detail of the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa of Avila by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

A study of Hinduism reveals a long history of the cultivation of ecstasy and associated states of consciousness. Hinduism’s earliest texts, the Vedas, spoke of a divine plant called soma that brought ecstasy. Soma was offered in sacrifice to the gods, and Indra, the god of thunder, was particularly fond of its intoxicating effects. The priests also drank the soma that was pressed during the sacrifice—all the while singing hymns to its power. In the Up-anishads, ecstasy was understood as a kind of gnosis in which one overcomes ignorance of one’s true nature. Salvation or release (moksa) comes essentially from intellectually “standing outside” one’s own position in the phenomenal world and realizing the fundamental connection of one’s own soul (Atman) with the underlying essence of the existence (Brahman). The ecstatic experience resulting from this realization has been given a variety of names, ranging from isolation, or kaivalya, to absorption, or samadhi.

More common is the understanding of ecstasy simply as the joy of union with the divine. The Gita Govinda uses sexual imagery to describe the union of the god Krishna with his devotees. The mystic Ramakrishna was reported to spend hours in a trance-like state beholding his mother, the goddess Kali. During the festival celebrating the god Shiva, devotees will often consume a cannabis preparation called bhang and chant the praises of Shiva for hours on end. What unifies these diverse expressions of ecstasy is a belief in the cosmic power of joy (annanda) and love (sneh).

When ecstasy is literally understood as “standing outside oneself,” it becomes rather problematic when applied to Buddhism and its doctrine of “no-self.” But a less restrictive understanding of ecstasy as an altered state of consciousness would apply to Buddhist understandings of the stages of enlightenment in Mahayana Buddhism. Specifically, the experience of “brightness” or prabhakari refers to the experience of being awakened to the fundamental nature of reality as impermanent; sudurjaya, or “invicibility,” describes both the experience and the result of denying the power of desire; and durangama, “going far away,” is the term used when the enlightened person resolves to remain in the world for the benefit of others. What makes these experiences and states ecstatic is how they reflect a radical shifting of perspective or a coming out of oneself. While the final state of extinction—or nirvana—is often understood to be ineffable, it is sometimes likened to bliss. For example, a display of rainbows, various supernatural entities, and a cascade of flower blossoms accompanied the death of Milarepa, the eleventh-century Tibetan yogic master. Mi-larepa’s entrance into nirvana was an ecstatic experience not only for him but also for those who observed his triumph over ignorance and desire.