In This Chapter

Getting to know your yarn Choosing your needles Stocking your knitting bag before you start knitting, you need a few supplies. Unlike many hobbies, though, knit-^^ting doesn’t require a lot of fancy equipment. In fact, one of the great allures of knitting, I think, is that the technology is about as basic as you can get: a couple of pointy sticks and some string. With these simple tools you can create even the most intricate projects, just as others have done for centuries. This chapter guides you through choosing the right yarns, needles, and other little gadgets that make your knitting easier.

Unraveling the Basics of Yarn

The first thing you need for knitting is yarn. You can find yarn in lots of places — in drug stores, at craft emporiums, and on the Internet — but the best place to go is your local knitting shop. Hanging out at a yarn store can make you feel like the proverbial kid in a candy shop; there are so many beautiful colors, textures, and fibers to look at and touch. A yarn store will likely have most of the yarns called for in the patterns in this topic. Plus yarn stores have knowledgeable and helpful staff members that can guide you in selecting yarns and projects that are just right for you.

In the following sections, I explain some yarn basics, including the different ways yarn is put up, the important information found on a yarn label, selecting the right yarn for a project (if you want to use something different from the pattern’s suggested yarn), and knowing how much yarn to buy.

Checking out different types of packaging

Yarns come put up, or packaged, in a variety of ways. They can be wound into balls or skeins, or they may come in hanks, which you wind into balls yourself. It doesn’t matter which way your yarn comes put up, so don’t worry if you have yarn in skeins and the pattern asks for balls.

If the yarn you’re using comes in a hank, you must wind it into a ball before you can knit it. To do so, take off the label and follow these steps:

1. Untwist the hank so that it opens into a circle.

Place this circle onto the back of a chair, someone’s outstretched hands, or a swift (a tool that looks like a wooden umbrella, which is specially designed for this task). Untie the short loops of yarn that hold the hank together.

2. Take one of the ends and begin winding the yarn into a ball.

Begin winding around two or three fingers, and then, as the ball is established, wind around the ball. Don’t wrap tightly or pull the yarn; it’s best to keep the yarn relaxed as you wind. As long as the circle of the hank is uncompromised, you shouldn’t get any tangles as you wind. However, mess with the circle and you’ll end up with a Girl Scout Badge in knots. Go slowly, and be patient if you have to do some untangling.

Reading a yarn (abet

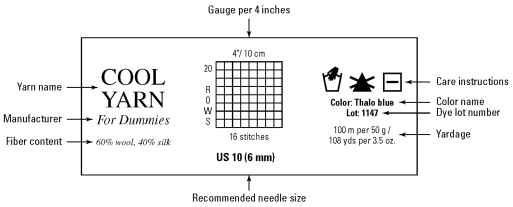

Every yarn you buy comes with a label. The label is filled with really important information, so don’t just throw it away. Take a look at the label in Figure 1-1 (or at the ones in your yarn basket) to find the information described in this list:

Name and manufacturer: Each label gives you the name of the manufacturer and the name of the yarn. Yarn names can be descriptive, evocative, or just silly. If you’re looking for a certain yarn, ask for it by its name and manufacturer.

Fiber content: The fiber content tells you what the yarn is made of. Yarns can be made of wool, cotton, synthetics, exotic animal and plant fibers, or blends of different fibers. If you’re looking for a substitute for a given project, consider the fiber content as well as the suggested gauge, because different fibers behave in different ways. I discuss fiber content and weight in more detail later in this chapter.

Gauge and suggested needle size: Remember that the label’s gauge and needle suggestions are just that: suggestions. So, no matter what the label says, you should swatch with the yarn to make sure that you’re getting the right gauge for your project before you begin knitting. See Chapter 2 for more on gauge and swatching.

The gauge may be written out like this: “4 stitches/inch on US 10 needles.” Or there may be a funny little grid with some numbers. If there’s a grid, here are some tips on how to read it:

• The grid always represents 4 inches (10 cm).

• The number along the bottom is the number of stitches per 4 inches. In Figure 1-1, this number is 16.

• The number along the side is the suggested number of rows per 4 inches. In Figure 1-1, this number is 20.

The grid in Figure 1-1 tells you that the manufacturer thinks the yarn will look best if you knit 16 stitches and 20 rows per 4 inches, likely on size 10 needles. So, if you wanted to, you could substitute this yarn in patterns that call for a gauge of “16 stitches/20 rows per 4 inches.” You can probably use it for something that calls for 15 or 17 stitches per 4 inches, but probably not for 12 or 20 stitches per 4 inches.

Care instructions: Most yarn labels contain information on caring for your finished projects (which is one reason to save the label in a notebook or file!). A year from now when you decide to wash your hat, you’ll likely need to reread this information. (Chapter 18 offers lots of tips for caring for your handknits.)

Color name and dye lot number: The color name may be a specific color, such as Fuchsia, or it may be just a color number, such as #322 (or it may be both). Many yarns also offer a dye lot number. Some yarns vary significantly depending on when they were dyed, particularly hand-dyed yarns. Whenever possible, stick to one dye lot when you’re selecting your yarns so that your project will have a uniform color. Sometimes the differences between dye lots are subtle enough that you won’t notice them while you’re knitting, and they’ll become apparent only when you wear your finished garment in the sunlight the first time!

Length and weight: Yarns are usually packaged in standard weights. A weight of 50 grams (1% ounces) is typical, but some skeins weigh 100 grams or more. The yarn label tells you how many yards or meters are in the skein. Use the yardage numbers rather than weight to figure out how much yarn to buy. Check out the section “Determining how much yarn you need” later in this chapter for more on this task.

Choosing the right yarn for the job

Deciding which yarn to use for a project can be a challenge because there’s much more to choosing the right yarn than deciding what your favorite color is! Each project in this topic calls for a specific yarn, but that doesn’t mean that you need to use that exact yarn. Part of what makes knitting fun is that by choosing yarns and colors that appeal to you, you make something that’s truly your own.

Consider the fabric that the yarn will make based on its fiber content and decide whether that fabric is appropriate for the pattern you’ve chosen. A pattern designed for a whisper-light mohair won’t look the same if you knit it in cotton chenille! You’ll also need to consider the weight of the yarn; read more about weight and matching gauge later in this chapter.

Find out a bit about the different sorts of yarn in the following sections so that you can choose your yarns with confidence.

Figure 1-1:

Yarn labels contain lots of useful information.

Fibers

Talking about the fibers used to make yarn starts like a game of Twenty Questions. Is it animal, vegetable, or mineral? Each of these categories has certain characteristics that influence how the yarn behaves and knits up. Here are the categories:

Animal Fibers: When you think of yarn, you may first think of wool. And there’s good reason for that. Sheep’s wool has been spun into yarn for a long time. It’s warm but breathable, is somewhat elastic, wears well, and is probably the easiest to knit with. Other animal fibers include alpaca, llama, mohair, angora, and cashmere. Silk is sort of a special case, because though it comes from bugs, it behaves more like a vegetable fiber than an animal fiber.

Unless they’re specially treated or blended with other fibers, animal fibers can turn to felt if you wash them in a machine. Buy superwash wool if you’re looking for easy-care yarn. (See Chapter 18 for more tips on caring for knits.)

Vegetable Fibers: Many yarns are made from plant fibers. These yarns are most commonly made of cotton, but you’ll also find ones made from linen, bamboo, and hemp. Vegetable fibers don’t have any natural elasticity and are generally heavier (though cooler!) than their wool counterparts. Still, cotton, linen, and the other vegetable fibers can be wonderful to knit with, and they make great knits to wear year-round.

Synthetics: Not so long ago, synthetic yarns meant that you were stuck with acrylic. If acrylic yarn still makes you think of those indestructible afghans that were knit in the mid-century, look around at what technology has done for yarn! There are many synthetics with exotic textures that knitters call novelty yarns. Whether they’re shiny, hairy, fuzzy, or bumpy, these yarns can add great texture and zing to your projects.

What’s really great about new synthetics is that there are now many blends that mix natural and man-made fibers to create wonderful, knittable yarns. For instance, adding a bit of microfiber acrylic to cotton makes a stretchier yarn; and adding rayon to wool creates a wonderful sheen and minimizes the itch of wool. Synthetic blends can make yarns that are sturdier and easier to care for. They also make luxury fibers easier on the pocketbook.

Weights

Regardless of their fiber content, yarns are classed by weight. This classification can throw knitters off because it really doesn’t have much to do with what the yarn actually weighs. The term “yarn weight” is a holdover from the days when most knitting was done with pure wool and there wasn’t such a rich cornucopia of yarns to choose from. In those days, you could count on 50 grams of worsted wool measuring just about 100 meters. But with the addition of so many new fibers to the marketplace and new ways to make yarn, you shouldn’t assume that 50 grams of one yarn is equivalent to 50 grams of another yarn. Yarn weight classes, such as “worsted” or “fingering,” are used to describe how thick the yarn is. So, look at the gauge listed on the label, not the weight of the skein, to determine which weight class your yarn fits into.

The Craft Yarn Council of America has created a standardized set of six weight classes, which are shown in Table 1-1. You can see, for instance, that bulky yarns knit at a gauge of between 12 and 15 stitches per 4 inches. However, don’t be fooled into thinking that yarns within one category are all the same and therefore interchangeable. Instead, these standards simply allow you to have a general sense of whether a yarn is, say, medium or bulky.

| Table 1-1 | Yarn Classes | |||

| Yarn Weight Category Name | Types of Yarn in Category | Knit Gauge Range in Stockinette Stitch per 4 inches | Recommended US Needle Sizes | Recommended Metric Needle Sizes |

| 1 Superfine | sock, fingering, baby | 27 to 32 sts | 1 to 3 | 2.25 to 3.25 mm |

| 2 Fine | sport, baby | 23 to 26 sts | 3 to 5 | 3.25 to 3.75 mm |

| 3 Light | DK, light worsted | 21 to 24 sts | 5 to 7 | 3.75 to 4.5 mm |

| 4 Medium | worsted, aran | 16 to 20 sts | 7 to 9 | 4.5 to 5.5 mm |

| Yarn Weight | Types of Yarn in | Knit Gauge | Recommended | Recommended |

| Category Name | Category | Range in | US Needle | Metric Needle |

| Stockinette | Sizes | Sizes | ||

| Stitch per | ||||

| 4 inches | ||||

| 5 Bulky | chunky, craft, rug | 12 to 15 sts | 9 to 11 | 5.5 to 8 mm |

| 6 Super bulky | bulky, roving | 6 to 11 sts | 11 and larger | 8 mm and larger |

Generally, you use small needles with the thinnest yarns and very large needles with the thickest yarns. Table 1-1 suggests a range of needle sizes that are commonly used with yarns of different weights. But remember that the size of needle that you need depends also on what you’re making and what your knitting style is. I discuss needle sizes later in this chapter.

Determining how much yarn you need

Whenever you start a new project, you have to know how much yarn you need. In the following sections, you find out the calculations to make, whether you’re substituting one yarn for another in a pattern or whether you just have a general sense of what you’d like to knit, say, a hat or a scarf.

Patterns usually call for a little more yarn than you’ll actually use, but because you want to swatch and account for the unknown (you actually hate three-quarter sleeves, you want to make a larger collar, or there’s been some terrible yarn accident), buy a little extra yarn, particularly if it’s being discontinued. Buying extra yarn also is a good idea because a ribbed or cabled pattern takes more yarn than stockinette stitch, and your knitting may vary. One extra ball is plenty for a small project; buy a couple of extra balls for a very large project. If you don’t use the extra yarn, most yarn shops allow you to return unused balls in good condition for store credit; be sure to ask about the store’s return policy before you buy. And remember that there are great uses for odd balls, too.

Calculating yardage when you’re substituting yarns

When you buy yarn, you obviously need enough to finish your project. But how much do you need? If you’re using the yarn called for in a pattern, the pattern usually tells you how many balls to buy for each size. However, if you choose to use a yarn different from the pattern’s suggestion, you may need to do a little calculating.

For instance, imagine that you want to knit a vest from a pattern that calls for eight skeins that each have 75 yards of yarn. But the yarn you want to use (that knits to the same gauge, of course!) has 109 yards per ball. How many balls should you buy?

This sounds like a story problem from my daughter’s math homework. And you can solve it just the way she would — by simply plugging in numbers. Use this general formula to determine how much yarn you need:

Number of skeins called for in the pattern x yards per skein = total yards needed for the pattern

Total yards needed for the pattern * yards per skein of your chosen yarn = number of skeins you need (round up to the nearest whole number, if necessary)

Using my vest example, the math works out like this:

8 skeins x 75 yards per skein = 600 yards

600 yards 109 yards per ball = 5)2 balls of yarn

So, because you can’t buy five and a half balls of yarn, you need to buy six balls to make your vest.

Estimating your yarn needs when you’re knitting on the fly

In the previous scenario, it’s easy to decide how much yarn to buy, but many times you don’t have all the variables decided. For example, if you aren’t working directly from a pattern or are working at a different gauge than a pattern recommends, you don’t have a tidy way to determine how much yarn to buy. Or say you happen by a really big yarn sale. There’s some wonderful wool on sale, but how much should you buy if you know you want to knit a sweater but haven’t chosen a pattern yet? One approach is to just buy it all and sort it out later. A more cautioned approach is to decide on the garment you want to make and guesstimate how much you need. Table 1-2 gives yardage approximations for various projects in a variety of gauges.

| Table 1-2 | Estimates of Yards of Yarn Needed for Projects | |||

| Yarn Weight Category | Stitches per Inch | Yards Needed for a Hat | Yards Needed for a Scarf |

Yards Needed for an Adult Sweater |

| 1 Superfine | 7 to 8 | 300 to 375 | 350 | 1,500 to 3,200 |

| 2 Fine | 6 to 7 | 250 to 350 | 300 | 1,200 to 2,500 |

| 3 Light | 5 to 6 | 200 to 300 | 250 | 1,000 to 2,000 |

| 4 Medium | 4 to 5 | 150 to 250 | 200 | 800 to 1,500 |

| 5 Bulky | 3 to 4 | 125 to 200 | 150 | 600 to 1,200 |

| 6 Super bulky | 1.5 to 3 | 75 to 125 | 125 | 400 to 800 |

If you like more precision, take a look at Table 1-3, which tells you how many inches of yarn you need to knit one square inch at a variety of gauges.

| Table 1-3 | Yarn Needed to Knit One Square Inch | ||

| Yarn Weight Category | Stitches per Inch | Rows per Inch Inches of Yarn Needed | |

| 1 Superfine | 7 to 8 | 10 | 28 |

| 2 Fine | 6 to 7 | 26 | |

| 3 Light (DK) | 5Yi to 6 | 7J2 | 24 |

| 3 Light (light worsted) | 5 to 5Yi | 7 | 22 |

| 4 Medium (worsted) | 5 | 6J2 | 20 |

| 4 Medium (aran) | 4 to 4Yi | 6 | 8 |

| 5 Bulky | 3 to 4 | 5 | 14 |

| 6 Super bulky | 1J2 to 3 | 4 | 12 |

Using Table 1-3 is pretty easy if you’re making a scarf, but it’s a bit more involved for something like a sweater. Still, it all comes down to geometry. For each piece of your project, multiply the length of the piece by the width, and then multiply this result by the length of yarn used per knitted inch. Here’s how it works:

Length x width x the length of yarn per knitted inch = inches of yarn needed Inches of yarn needed ^ 36 inches per yard = number of yards of yarn

Suppose you’re making a scarf that’s 60 inches long and 6 inches wide. You’re using a medium weight yarn that knits to a gauge of 5 stitches per inch. With this gauge, Table 1-3 shows that you need 20 inches of yarn to knit a square inch. Multiply 60 by 6 by 20, and you need 7,200 inches of yarn. Divide that number by 36 inches in a yard and you get 200 yards.

Getting to the Point of Needles

The other must-have for knitting (besides yarn, of course!) is needles. While there aren’t as many kinds of needles as there are kinds of yarn, you still have a lot to choose from and the decision of what to buy (or use) can be a bit bewildering. Read through the following sections to get a handle on your needle options.

Looking at different kinds of needles

It won’t surprise you that knitters have preferences when it comes to yarn, but it may surprise you that sometimes their preferences for needles are even stronger. I like to knit on metal circular needles and find it faintly annoying to knit on anything else. Then again, I know tremendously skilled knitters who love straight, wooden needles. There’s no right or wrong here. Take the opportunity to try out different needles to see what you like best.

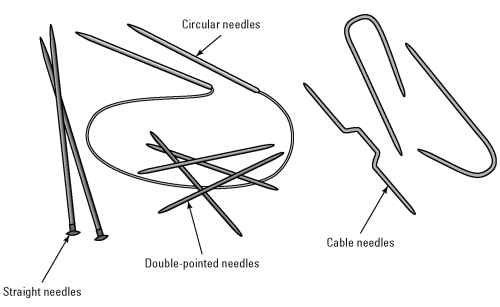

Needles generally fit into a few basic categories, including straight needles, circular needles, double-pointed needles, and cable needles. You can see what they look like in Figure 1-2. Here are the characteristics of each:

Straight needles: The most classic knitting needles are straight needles, which are about 14 inches long and made of metal or wood. They have a point on one end and a stopper of some sort on the opposite end to keep the stitches from falling off. You can knit almost anything on these, except for those projects that were designed to be knit in the round (see Chapter 11) or something extremely wide, such as a blanket. You can get shorter 10-inch length needles also, which are a bit more manageable for something like a scarf. These shorter needles are also easier to tuck into your bag.

Circular needles: These needles have two pointy ends connected by a cable. They come in different lengths as well as different gauges. The length of a circular needle is measured from tip to tip. A pattern will specify which length you need for your project. For instance, to knit a hat you need a short length, such as 16 inches. A sweater, on the other hand, knits up on a needle that’s 24 or 36 inches long. If you’re knitting something with a huge number of stitches (like a blanket or the shawl collar on the coats in Chapter 10), you may need an even longer needle.

Note that you can use circular needles even if you aren’t knitting in the round. Just like you do with straight needles, turn the work around at the end of the row and switch the needle tips to the opposite hands. Think of your circular needle as two straight needles that happen to be stuck together. Some knitters prefer circular needles for all their projects because it’s more difficult to lose a needle and because it keeps the weight of the knitting more centered in your lap. If you have trouble with repetitive stress injuries, circular needles may lessen the strain on your wrists.

Double-pointed needles: Double-pointed needles are used less often than straight and circular needles, unless you make a lot of socks. Double-pointed needles look like large toothpicks and come in sets of four or five. These needles are used to knit in the round to create tubes that are smaller than you can make on a single circular needle, mainly socks and the tops of hats.

Cable needles: Cable needles come in a few different varieties. Some are shaped like U’s or J’s; others are like short double-pointed needles with a narrow or bent spot in the center. One sort doesn’t work better than another, so if you’re having trouble with the one you’ve got, experiment a little with a different type. Read more about cables in Chapter 6.

Figure 1-2:

Different needles for different jobs.

Needles, whether circular or straight, can be made out of a variety of things: aluminum, steel, bamboo, exotic hardwoods, plastic, and even glass. The weight, price, slipperi-ness, and even the noise that the needles make can influence which needle is right for you. As a very general rule of thumb, use a slippery needle like metal for yarns that are sticky or catchy, such as mohair or chenille. Conversely, with slippery yarns, such as some ribbons and novelty yarns, try needles that are a little less smooth, like bamboo. As you take on new projects, you’re likely to need different-sized needles every now and then. Why not try a needle made from something new the next time you buy?

Understanding needle sizes

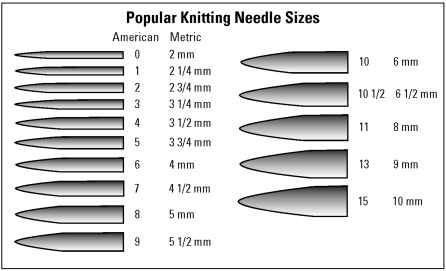

Needles come in a range of sizes based on the diameter of the needle. In the United States, needles are numbered according to a somewhat logical but obscure system. It starts out okay with 0, 1, 2, and so on, but then it gets weird later with 9, 10, 10/2, 11, 13, 15, and so on. Most of the rest of the world relies on the metric system to size knitting needles, so you’ll also see needle sizes like 5 mm and 8 mm. You can compare metric and US needle sizes by looking at Figure 1-3.

Figure 1-3:

Needles come in a variety of sizes.

If you’re reading a pattern that was written in Europe or you’re reading the suggested needle size from a yarn label printed outside the United States, take note of whether the needle sizes are given in metric or US form. That way, you’ll be sure to use the right size.

If you’re having trouble deciding which size needle is right for the yarn you’ve chosen, check out Table 1-1 to help guide you to the right needles.

Filling Your Knitting Bag with Other Gadgets

Some people have absolutely every accessory for their craft. Others wander around with their stuff tossed into a grocery sack. And while I adore looking at someone’s beautifully styled knitting bag with matching needle holder and cellphone cozy, I also admire the less-is-more approach; you can knit happily for years with a simple bag, a couple pairs of needles, and whatever yarn comes your way. And for the most part, you don’t need specialized tools (see Chapter 17 for ways to MacGyver your knitting with everyday items).

Think for a moment about what you knit and where you knit it. If you mainly knit socks during your commute on the bus, you’ll need a small bag to hold your project — likely something that tucks into your purse (or is your purse). If you’re knitting a bulky Fair Isle sweater at home in front of the fire, however, you don’t have to worry about carrying things around, in which case you might use a large basket to hold your work-in-progress and extra yarns. Realistically, if you fall for knitting in a big way, you’ll have a sock in your purse, the basket by the fire, a simple scarf waiting by the TV, and maybe something stashed in the car for some sort of knitting emergency. Wherever you knit, the following sections list some tools that come in handy.

Measuring tools

If you want a garment to fit properly, you have to measure it properly. And it never hurts to measure yourself either (see Chapter 3 for more on measuring yourself). Here are a few tools that can help you master measurements and numbers when knitting:

‘ Tape measure: A small cloth tape measure that retracts is handy. A plastic tape measure is okay too, though it may stretch out over time. Metal tape measures are great for carpenters but not so good for knitters because they aren’t flexible enough.

Gauge measurement tool: When searching for your own gauge measurement tool, you have a couple of different models to choose from. Some are metal and some are plastic. They all have a window that allows you to count the number of stitches and rows per two inches, which helps you to see whether you’re knitting to the gauge specified. These tools also feature holes with different diameters to check the size of your needles. You can measure gauge just fine with a tape measure, but a gauge measurement tool is pretty handy to have. (Find out more about gauge and see a gauge measurement tool in Chapter 2.)

Calculator: I find it useful to have a calculator with my knitting paraphernalia because there are times when calculations come up. I applaud both the scrap-of-paper and the in-the-head techniques, but most knitters prefer to use a calculator.

Markers and holders

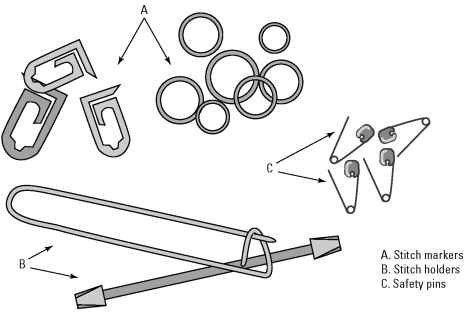

Knitters use a variety of tools to mark particular spots in their knitting and to hold live stitches. (Live stitches are stitches that you aren’t working with at the moment, but that you’ll do more with later.) Shoulder stitches that will later be bound off with the three-needle bind-off or the stitches for half the neckline after you’ve divided the left and right neck are common examples of stitches that you may want to put on a holder. Check out these marking and holding tools, which are shown in Figure 1-4:

Markers: Knitters sometimes need to leave a mark to note a stopping or starting place. There are several different sorts of markers for this purpose. If you want an easy way to spot where you started your armhole decreases, for instance, you place a marker on a stitch in that row and leave it there so you can measure from it later. Markers used for this purpose are often called split ring markers or locking markers. More often, though, you’ll use markers on your needle. Markers used in this way are sometimes called ring markers. These are placed on the needle between stitches and slipped from needle to needle whenever you encounter them.

Safety pins: You can use safety pins to remind yourself which is the right side of your work by pinning them through the fabric on that side (this is particularly helpful when your stitch pattern looks the same on both sides). This way, when the instructions read “Decrease at each end every right-side row” you know that if you can see the safety pin, it’s a decrease row.

Safety pins are also helpful when you notice a dropped stitch way down in your work. If you can’t fix it (or you can’t fix it at the moment), put the dropped stitch onto the safety pin and pin it to its neighbor. The stitch will be safe until help arrives. Coilless pins are particularly nice because the yarn doesn’t catch on them and they can hold more stitches.

Figure 1-4:

Tools to help you mark and hold your stitches.

Holders: A safety pin is a great stitch holder for a few stitches, but if you have more than you can fit on your pin, you need to resort to something else. In this case, that something else is a stitch holder. The old-school models look like kilt pins. Newer varieties look a bit like hair curlers and have the advantage of opening on each end so you can access the stitches from either side. A spare needle or length of smooth scrap yarn can also hold your stitches for you.

Whatever kind of holder you use, slip the specified stitches to the holder purlwise. When it’s time to address these stitches again, slip them back to the working needle, again slipping purlwise so the stitches aren’t twisted.

Tools for keeping track of your knitting

When knitting, you’ll find that there are inevitably little bits of information that you want to write down. Whether you need to remind yourself that you’re on Row 27 or you need to remember the title of a recommended topic or the name of the yarn the person next to you in class was using for her shawl, something to write on often comes in handy. The grocery-bag-toting knitter will make do with a receipt or another piece of scrap paper, but it’s smart to carry a notebook for your knitting ideas. And don’t forget to throw in something to write with.

Many knitters also like to make photocopies of the patterns that they’re working on. While you’re at it, feel free to enlarge any charts so they’re easy for you to read. With the copy, you’re free to make your notes right on the pattern.

Sticky notes can come in handy too. You can use them to mark your place in this topic, or you can make tally marks on them as you finish your rows. If you’re using a chart, it’s handy to place the sticky note right under the row that you’re working on so you don’t get lost every time you look from your topic to the knitting and back again.

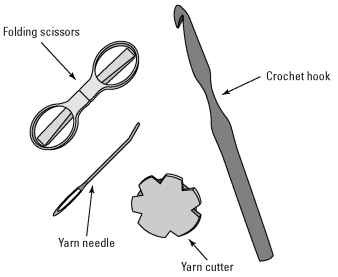

Finishing tools

Most patterns have a section called “Finishing.” Usually this means sewing up and blocking (see the appendix for details on these tasks). Parts of finishing are simply more knitting, but here are a couple of other tools that you want to have that help get the job done (see Figure 1-5):

Yarn needles: Sometimes called tapestry needles, yarn needles look like big, fat sewing needles with a blunt tip. Some are straight and some have a bit of a curve at the tip, which helps you scoop up stitches. But be sure to choose a needle meant for yarn! Upholstery needles are nice and big, but anything with a sharp tip will lead you to frustration because you’ll tend to sew into the yarn instead of going between stitches. Even a kid’s plastic needle will work better than a sharp one.

Crochet hooks: Even though you’re knitting, a crochet hook or two can come in handy. Generally, you want one about the diameter of the needles that you’re working with, or a size or two smaller. Aside from basic crochet used for edging and such, a crochet hook can help you pick up stitches, fix errors, or weave in your ends.

Scissors: Though you can break most yarns with your hands, scissors do come in handy. Choose blunt-tipped or folding scissors to prevent nasty pokes if you carry them around with you.

If you’re traveling by air and want to take your knitting on board, consider buying a yarn cutter like the one shown in Figure 1-5, since most scissors aren’t allowed on planes.

Figure 1-5:

Handy finishing tools you want to have around.