AKIROV, ALFRED

(1941- ), Israeli entrpreneur. Akirov built a business empire ranging from real estate and hotels to high-tech, securing his position as one of the country’s leading businessman, known for his determination and sound business instincts. He was born in Iraq in 1941 and immigrated in his childhood to Israel with his parents. He started working in construction in the family business and then struck out on his own. After a couple of business ventures, including participation in the acquisition of the Arkia Airline and a textile company, he set up his own holding company, Elrov, in 1978.

The company, which was listed on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange in 1983, was active in two core businesses: real estate and technology and communication. Akirov demonstrated his expertise in the property business by building some of Israel’s best-known development projects, including the Europe Building and the Opera Tower in Tel Aviv. The company also built and owns several large shopping malls in Israel’s central area.

As the Israeli economy entered its worst economic recession in 2000, Elrov shifted part of its focus to overseas activity and the company acquired commercial centers in Switzerland, England, France, and the United States.

Akirov won fame with the building of the David Citadel, Jerusalem’s most luxurious hotel, overlooking the walls of the capital’s Old City. Plans to develop a nearby $150 million project, known as the Mamilla project, which included an upscale residential and business area, ran into difficulties after a long dispute with the municipality of Jerusalem.

Elrov also invested, through its Technorov subsidiary, in some of Israel’s most promising high-tech start-ups and venture capital funds. However, the burst of the high-tech bubble in 2000 forced the company to write off much of its investment.

AKIVA

(c. 50-135 c.e.), one of the most outstanding tannaim, probably the foremost scholar of his age. A teacher and martyr, he exercised a decisive influence in the development of the halakhah. A history of Akiva’s scholarly activities – his relations to his teachers, R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus, R. Joshua b. Hananiah, Rabban Gamaliel ii, and to his disciples, R. *Meir, R. *Simeon b. Yohai, R. *Yose b. H alafta, R. *Eleazar b. Sham-mua, and R. *Nehemiah – would be virtually identical to a history of tannaitic literature itself. The content of Akiva’s teaching is preserved for us in the many traditions transmitted and interpreted by his students, which make up the vast majority of the material included in the Mishnah, the Tosefta, and the Midreshei Halakhah. Later tradition regarded Akiva as "one of the fathers of the world" (tj, Shek. 3:1, 47b), and credited him with systematizing the halakhot and the aggadot (tj, Shek. 5:1, 48c).

In the eyes of later storytellers, the period of the tan-naim was a heroic age, and even the slightest scrap of information about the least of the tannaim can develop in the later aggadah into a tale of epic proportions. In the case of truly significant and heroic figures, like R. Akiva, this process of literary expansion and elaboration is inevitable. The resulting legends relating to Akiva’s life and death are well known (see bibliography below), and we will summarize a few of them in outline here:

The Bavli tells that in his early years Akiva was not only unlearned, an am ha-arez, but also a bitter enemy of scholars: "When I was an am ha-arez I said, ‘Had I a scholar in my power, I would maul him like an ass’" (Pes. 49b). Of relatively humble parentage (Ber. 27b), Akiva was employed as a shepherd in his early years by (Bar) Kalba Savu’a, one of the wealthiest men in Jerusalem (Ned. 50a; Ket. 62b). The latter’s opposition to his daughter Rachel’s marriage to Akiva led him to cut them both off. Abandoned to extreme poverty, Rachel once even sold her hair for food. Rachel made her marriage to Akiva conditional upon his devoting himself to Torah study. Leaving his wife behind, Akiva was away from home for 12 years (according to Avot de-Rabbi Nathan – 13 years). The Talmud relates that when Akiva, accompanied by 12,000 students, returned home after an absence of 12 years he overheard his wife telling a neighbor that she would willingly wait another 12 years if within that time he could increase his learning twofold. Hearing this, he left without revealing himself to her, and returned 12 years later with 24,000 students. Later in his career, Akiva was imprisoned by the Romans for openly teaching the Torah in defiance of their edict (Sanh. 12a). When Pappos b. Judah urged him to desist from studying and teaching in view of the Roman decree making it a capital offense, he answered with the parable of the fox which urged a fish to come up on dry land to escape the fisherman’s net. The fish answered "’If we are afraid in the element in which we live, how much more should we be afraid when we are out of that element. We should then surely die.’ So it is with us with regard to the study of the Torah, which is ‘thy life and the length of thy days’" (Ber. 61b). He was not immediately executed and was reportedly allowed visitors (Pes. 112a; but cf. tj, Yev. 12:5, 12d). Akiva was subsequently tortured to death by the Romans by having his flesh torn from his body with "iron combs." He bore his sufferings with fortitude, welcoming his martyrdom as a unique opportunity of fulfilling the precept, "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart and with all thy soul … even if you must pay for it with your life" (Ber. 61b).

Akiva also played a significant role in narratives which centered on the other great figures of his time. When R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus was excommunicated, it was Akiva who was chosen to break the news to him (bm 59b). In the controversy between Rabban Gamaliel ii and R. Joshua, Akiva attempted to effect a reconciliation between them (Ber. 27b-28c; cf. rh 2:9).

Granting the literary and religious power of these legends, the modern critical reader must approach them with care. Take, for example, the tradition, brought above, which ascribes to Akiva in his early years a bitter hatred and antagonism toward rabbinic scholars. This tradition appears in the Bavli as part of an extended collection of similar traditions (Pes. 49a-b), ascribed to various rabbinic scholars from the Land of Israel in the 2nd and 3rf centuries. S. Wald has shown (Pesahim iii, 211-239) that this entire talmudic passage is a product of late tendentious revision of earlier sources, reflecting the antagonism between later Babylonian sages and their real or imagined interlocutors – ame ha-arez in their terminology. With regard to R. Akiva himself, this source must be viewed as pseudoepigraphic at best, and can neither be ascribed to him in any historical sense, nor can it be reconciled with other traditional accounts of his early life. For example, in the Talmud Yerushalmi (Naz. 7:1, 66a) we hear a very different story: "R. Akiva said: This is how I became a disciple of the sages. Once I was walking by the way and I came across a dead body [met mitzvah]. I carried it for four miles until I came to a cemetery and buried it. When I came to R. Yehoshua and R. Eliezer I told them what I had done. They told me: ‘For every step you took, it is as if you spilled blood.’ I said: ‘If in a case where I intended to do good, I was found guilty, in a case where I did not intend to do good, I most certainly will be found guilty!’ From that moment on, I became a disciple of the sages." The fact that Akiva in this story, while still an am ha-arez, both sought and expected the approval of the two sages who would in the future be his closest teachers, clearly contradicts the notion that at this stage in his life he both hated and held the sages in contempt.

Admittedly, we have no clear and compelling reason to accept the Yerushalmi’s version of events as historically accurate. Nevertheless the very fact that it gives us an alternative version of how Akiva "became a disciple of the sages" raises questions – at the very least – about the historical reliability of the Bavli’s story about Kalba Savu’a and his daughter. These traditions have themselves been the subject of intense study, most recently by S. Friedman, who traced the evolution of these stories within the Babylonian rabbinic tradition. Given the number and complexity of the traditions surrounding the figure of R. Akiva, it will in all likelihood be some time before it will be possible to evaluate their relative historical value and the religious, social, and literary tendencies imbedded in them.

Among the early traditions ascribed to Akiva in the Mishnah, we find him affirming the ideas of free will and God’s omniscience, "Everything is foreseen, and free will is given" (Avot 3:15). He taught that a sinner achieves atonement by immersion in God’s mercy, just as impurity is removed by the immersion in the waters of a mikveh (Yoma 8:9). Akiva is reported to have said: "Beloved is a man in that he was created in the image [of God]" (Avot 3:18), and held that "Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself" is the most fundamental principle of the Torah (Sifra, Kedoshim, Ch. 4:13). Akiva’s insistence that the Song of Songs be regarded as an integral part of the canon – "All the Writings are holy; but the Song of Songs is Holy of Holies" (Yad, 3:5) – may be related to his mystical interests (Lieberman, Mishnat Shir ha-Shirim). According to Tosefta Hagigah (2:2), Akiva received instruction in the mystical traditions concerning the divine merkavah from R. Joshua, who himself received these traditions from R. Johanan b. Za-kkai. In addition, R. Akiva is counted as one of the four sages who "entered the pardes," and was the only one of the four who "ascended in peace and descended in peace," i.e., participated in this mystical experience and emerged unharmed. As a result of these traditions, R. Akiva became the protagonist of Heikhalot Zutarti, one of the earlier works of the heikhalot literature, imparting instructions to the initiate concerning the dangers involved in ascending to heaven and concerning the techniques necessary for evading these dangers.

For Akiva’s method of midrashic interpretation of scripture, and the school of Midrash Halakhah which bears his name, *Midrashei Halkhah.

AKIVA BAER BEN JOSEPH

(Simeon Akiva Baer; 17th century), talmudist and kabbalist. Akiva was among the Jews who were expelled from Vienna in 1670. He thereafter wandered through the whole of Bohemia and parts of Germany, earning his living by teaching Talmud and delivering lectures in the synagogue on the Sabbath. He interrupted his travels when he was elected rabbi of Burgpreppach, in Bavaria. There Akiva wrote a kabbalistic commentary on daily prayers entitled Avodat ha-Bore ("The Worship of the Creator," 1688), comprised of five parts, each beginning with one of the letters of his name (a.k.i.b.a.). This work met with success and was published three times. A new commentary for the Sabbath and holidays was added to the third edition. Akiva interrupted his travels a second time to become rabbi of Zeckendorf, near Bamberg.He remained in Zeckendorf six years. From there Akiva was called to Schnaitach, which at that time had a large Jewish community. There he was imprisoned during a riot. After his release, Akiva became rabbi of Gunzenhausen and, finally, second rabbi of Ans-bach. He was the author of two works in Yiddish, which had even a wider circulation than his Hebrew works, namely: Ab-bir Ya’akov ("The Mighty [God] of Jacob," 1700), a collection of legends from the Zohar and from the Midrash ha-Neelam about the patriarchs, based on the first 47 topics of Genesis; "Maasei Adonai" ("The Deeds of the Lord"), a collection of wondrous stories from the Zohar, from the works of Isaac Luria, and from other kabbalistic books.

AKIVA BEN MENAHEM HA-KOHEN OF OFEN

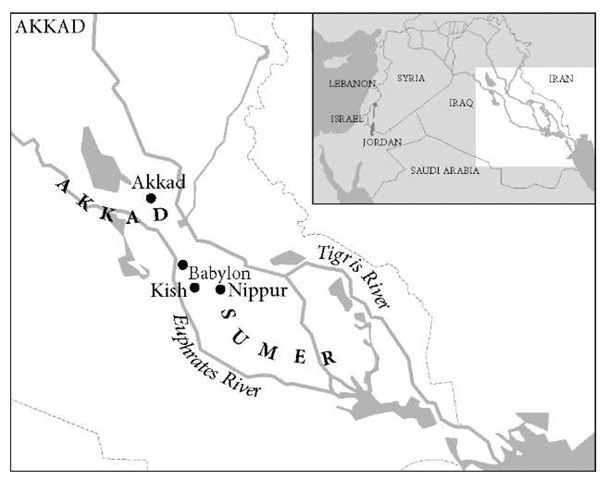

(Buda; second half of 15th century), Hungarian financial expert and scholar in Buda. After Jacob *Mendel, Akiva was the most influential Jew at the court of King Matthias i of Hungary (1458-90). Epitaphs of members of the family (in Prague) refer to him as nasi and "head of the entire Diaspora." In 1496 Akiva was still living in Buda. Later forced to leave Hungary Shinar (Sumer), according to the "table of nations" (Gen. 10:9-10). In the cuneiform sources, Akkad (Sumerian Agade or Aggide) refers to both a city and a country in northern Babylonia which first flourished as the seat of the "(Old) Akkadian" kings in the Sargonic period (c. 3380-3200 b.c.e.). The city’s exact location is still unknown, but it must have been situated on the (ancient) Euphrates, upstream from Nippur and not far from Babylon. According to tradition, it was founded by Sargon, a Semite who began his career at the court of the city of Kish. He assumed a name characteristic of a usurper (Sargon literally: "the king is legitimate") and the title "king of Kish." In this he was followed by his sons Rimush and Man-ishtusu. His grandson Naram-Sin assumed new titles and dignities and seems to have brought the Akkadian Empire to new heights, but in so doing he overreached himself. By the end of his reign, the rapid decline of the empire had begun. Later Sumerian tradition attributed this to Naram-Sin’s sins against the Temple of Enlil at Nippur, but modern scholarship tends to attribute it to the increasing inroads of the barbarian Gutians from the eastern highlands. Under Naram-Sin’s son, Shar-kali-sharri, Akkadian rule was progressively restricted, as the more modest title of "King of Akkad" attests. The decline and fall of the dynasty left a deep impression on the country: Naram-Sin was turned into a stereotype of the unfortunate ruler in later literature, and the "end of Agade" became not only a fixed point for subsequent chronology but also a type-case for omens and prophecies.

While the destruction of the city of Akkad was complete, the name of the country survived into later periods. The geographical expression "[land of] Sumer and [land of] Akkad" came to designate the central axis of Sumero-Akkadian political hegemony; i.e., the areas lying respectively northwest and southeast of Nippur. The kings who held that religious and cultural capital therefore assumed the title "king of Sumer and Akkad." They tended to replace it, or from Hammurapi on even to supplement it, with the loftier title of "king of the four quarters [of the world]" when to these two central lands they added the rule of the western and eastern lands, Amurru and Elam (see *Sumerians). From Middle Babylonian times on (1500-1000), the noun Akkad was used in the cuneiform sources as a virtual synonym for Babylonia.

AKKAD

(Heb. ![]() The adjective "Akkadian" was used in various senses by the ancients: originally it designated the Semitic speakers and speech of Mesopotamia as distinguished from the Sumerian, then the older Semitic stratum as distinguished from the more recent Semitic arrivals of *Amorite speech, and finally Babylonian as distinguished from Assyrian. In modern terminology, *Akkadian is used as a collective term for all the East Semitic dialects of Mesopotamia.

The adjective "Akkadian" was used in various senses by the ancients: originally it designated the Semitic speakers and speech of Mesopotamia as distinguished from the Sumerian, then the older Semitic stratum as distinguished from the more recent Semitic arrivals of *Amorite speech, and finally Babylonian as distinguished from Assyrian. In modern terminology, *Akkadian is used as a collective term for all the East Semitic dialects of Mesopotamia.

Which of these meanings best applies to the "Akkad" of Genesis 10:10 can only be answered in the context of the entire Nimrod pericope (Gen. 10:8-12) and of the identification of Nimrod. Probably the figure of Nimrod combines features pertaining to several heroic kings of the Mesopota-mian historic tradition, from Gilgamesh of Uruk to Tukulti-Ninurta 1 of Assur (see E.A. Speiser). However, the reference to Akkad as one of his first or capital cities points to the Old Akkadian period, and to its two principal monarchs, Sargon and Naram-Sin. Both were central figures of Mesopotamian historiography, and Naram-Sin in particular introduced the title of "mighty [man]" into the Mesopotamian titulary. Genesis 10:8 may reflect this innovation.

AKKADIAN LANGUAGE

Akkadian is the designation for a group of closely related East Semitic dialects current in Mesopotamia from the early third millennium until the Christian era. Closely connected to it is Eblaite, the language found at Tell Maradikh (ancient Ebla) in northern Syria.

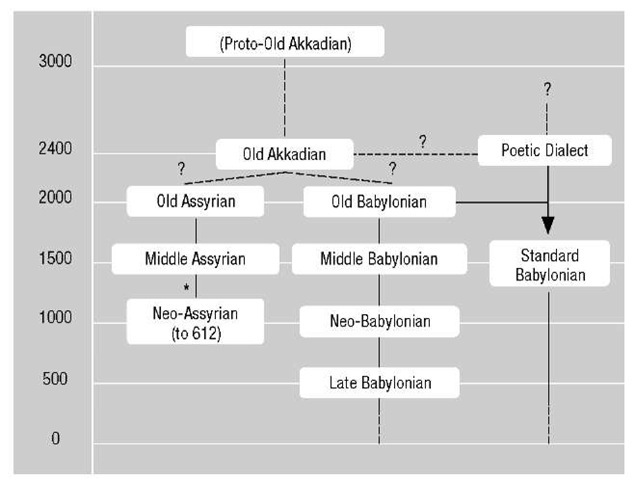

The name is derived from akkadum, the relative adjective of a.ga.de = *Akkad (biblical 13X), the capital of the Sargonic Empire (c. 2400 b.c.e.). It is not known what the speakers of one of the capital cities of *Nimrod in East Semitic in Mesopotamia called themselves or their speech prior to this period. The available textual evidence does not show any marked dialectical discontinuity between the pre-Sargonic and the Sargonic periods. The earliest textual occurrence is from the first dynasty of Ur (c. 2600 B.c.E.) and the latest from the first century c.e. The dialectical history of Akkadian can be schematically represented as follows:

* Linear development uncertain

The Old Akkadian corpus consists of royal inscriptions, economic documents, letters, and the occasional literary text from the pre-Sargonic, Sargonic, and Ur 111 periods (to c. 2000 b.c.e.). These texts, in particular the royal inscriptions, are in large measure known from Old Babylonian copies, products of the Nippur scribal school in southern Babylonia. Most of the other original material also comes from this region, but texts have been found further afield: in *Elam, northern Syria, and eastern Anatolia (Asia *Minor). It is not clear whether Old Akkadian is the parent of the later Akkadian dialects. While some obvious phonologic and morphologic isoglosses would seem to indicate that Old Assyrian is the descendant of Old Akkadian, the latter in other, more basic aspects, has much in common with Old Babylonian. However, both Old Assyrian and Old Babylonian may have evolved from other unknown and undocumented dialects. (On this point see M. Hilgert, "New Perspectives in the Study of Third Millennium Akkadian," Cuneiform Digital Library Journal, 4 (2003), 1-14.)

Assyrian

Old Assyrian is mainly known from letters and economic documents excavated in eastern Anatolia, chiefly in the lower city at Kultepe (ancient Kanis) where an Assyrian mercantile colony (karum) was located at the beginning of the second millennium. The corpus includes a small number of royal inscriptions and about a dozen literary texts, including some incantations; a few of the texts originated in *Assur and other north Mesopotamian sites, such as Nuzi.

The best known Middle Assyrian document is the so-called "Middle Assyrian laws" from Assur, dating from the middle and second half of the second millennium b.c.e. Economic and legal documents and letters are also attested.

Neo-Assyrian texts consist for the most part of letters and economic documents with a few literary texts. Documents written in this dialect come to an abrupt end with the destruction of Nineveh and other cities in 612 b.c.e. and the complete collapse of the Assyrian Empire shortly thereafter. It should be noted that the Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions are written in Standard Babylonian, as are the inscriptions of the dynasties ruling southern Babylonia in the first millennium b.c.e. The relative absence of legal material from the private sector seems to be due to an increasing use of Aramaic.

Babylonian

Old Babylonian is richly documented in large numbers of letters, economic records, state and legal documents, including the Code of Hammurapi, royal inscriptions, and a sizable corpus of literary texts consisting of hymns and various types of lyric and epic poetry. Several dialects, some showing substrate influence, can be discerned: a southern and northern dialect in Babylonia, a northeast dialect centered in the *Diyalah region, and provincial dialects such as those from Susa and *Mari. Literary texts are generally written in a poetic register (formally called "dialect") which exhibits archaic forms and syntax. This poetic dialect, the so-called "hymnic-epic dialect," could be either a survival of an earlier stage of the language or an older dialect with close affinities to Old Akkadian in a restricted stereotyped use. Post-Old Babylonian Akkadian literature from all centers is usually written in a linguistic register which is an artificial literary offshoot of Old Babylonian, and is influenced by archaic forms current in the older poetic dialect, called Standard Babylonian. Standard Babylonian was cultivated by the scribes for literary purposes from the middle of the second millennium and through the first millennium b.c.e. until Akkadian ceased to be used. Standard Babylonian suppressed literary creativity in local dialects, e.g., Assyrian, but it tends to show a strong influence of the locally spoken tongue.

Middle Babylonian is attested in letters, economic and official documents, and a few literary documents. While the size of the corpus of Middle Babylonian texts found in Mesopotamia proper is moderate, geographically this dialect (and variations of it) is the most widely spread and was used all over western Asia during the second millennium b.c.e. The Akkadian material from the archives of Bogazkoy and Ras Shamra (*Ugarit) are written in local forms of Middle Babylonian, as are the letters of El *Amarna found in Egypt, which, however, originated in Anatolia, Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia. The wide diffusion of Akkadian during the period was due to its use as a diplomatic language.

Neo-Babylonian is likewise represented mainly by a large corpus of non-literary sources, especially letters and economic documents. The use of the last surviving "living" dialect, Late Babylonian, petered out completely during the Seleucid period. Standard Babylonian continued to be in use in the temple scriptoria, in the transmission of canonical compositions, and in the compilation of astronomical texts which are the last remnant of the Mesopotamian tradition. The latest datable text so far recognized is an astronomical almanac written in 385 Seleucid era (74/75 c.E.).

Phonology

Akkadian is written with signs which apparently were originally devised for Sumerian. The application of the Sumerian system to Akkadian resulted in a mixed method of writing: on the one hand with logograms and, on the other, with syllables of the type vC, Cv, or CvC (C = consonant; v = vowel). The phonemic system and structure of Sumerian is radically different from that of Akkadian and the writing system consequently presented inadequacies which were only partially overcome during the long history of writing Akkadian. A phonological interpretation is likewise hindered due to a tendency toward historic writing.

Vowels. The vocalic phonemes represented are the long and short a, i, u, e. E does not seem to be original but is derived from a or i; e.g., ilqa’ > ilqe ("he took"), while i tends to become e, especially in Assyrian, and the etymologically long i became e already in Old Babylonian times. Rare mixed writings, e.g., ma-ru-is (Old Babylonian; "is sick"), have been used in attempts to demonstrate other vowel qualities, in this case the u-i sequence being taken as representing u. Greek transcriptions from the Seleucid period which reflect the pronunciation of Late Babylonian represent u by o, e.g., o(ov = uzun ("ear of"), and u by w, e.g., vwp = nur ("light of"). Diphthongs are monophthongized, e.g., tayn- > in- ("eye"), tmawt- > mut ("death"). (The double dagger, t, indicates the reconstructed form.) Pseudo-diphthongs, such as Old Babylonian nawrum ("bright"), probably represent nawirum. A basic characteristic of the Assyrian dialects is the vowel harmony operative with short unaccented a in an open syllable which assimilates progressively, e.g., awutum (nominative singular), awitim (genitive singular), awatam (accusative singular; "word"); in Babylonian: awatum, awatim, awatam. Vowel length is phonemic, e.g., sarratum ("queen"), sarratum ("queens").

Consonants. The considerable reduction in consonants characteristic of Akkadian (and of later forms of other Semitic languages, such as Hebrew and Aramaic), as compared to the theoretically reconstructed consonant phonemes of Proto-Semitic, or those of other Semitic languages such as Ugaritic or Arabic, is already evident in Old Akkadian. By the time of the earliest written Akkadian, the dentals d, t and d had shifted to z, s, and s respectively, while t was on its way to s but in Old Akkadian is distinguished graphically from etymological s and s.

The laryngeals for the most part merged with 5 or disappeared (Sumerian substrate influence?), compensating with the lengthening of the vowel and apophony, e.g., tbalum > belum ("lord"), although in Assyrian and some Babylonian dialects this process is not complete. In Old Akkadian 5 and h are at least partially distinct as shown by such writings a ra-si-im = rasim, later resim (genitive singular of "head") an the special use of the sign E as in il-qa- E = tilqah ("he took cf. Sumerian E.GAL > Akkadian ekallum > Hebrew Vd’H The influence of intrusive West Semitic dialects is reflecte in doublets, e.g., Old Babylonian hadannum for adannum ("fixed time," dn), Neo-Assyrian hannu for annu ("this," hn-(On laryngals see L. Kogan, "*g in Akkadian," uf, 33 (2001 263-98.)

Of the various phonological changes affecting consc nants as a result of environmental conditioning two should b mentioned. In the nominal patterns mapras and mupras (ex cept in certain nominal forms, e.g., the participle of the ver of the derived themes; see below) of roots containing a labi phoneme, m dissimilates to n (Barth’s Law), e.g., tmarkabtum > narkabtum ("chariot"). Likewise, in any given root one ( two emphatics dissimilate, viz, s > s (very rare), q > k, t > t – i this order of stability (Geers’ Law), e.g., tsabatuui >sabatum ("to seize"), tqasabu > kasabu ("to cut away").

Initial w disappeared already in Old Babyloniar e.g., warhu (Old Babylonian), arhu (post-Old Babylonian "month"). In Assyrian, wa- > (wu >) u, e.g., warhum > urhum Babylonian intervocalic -w- > -m-, e.g., awilum > amilum ("man"). In Assyrian, wa- > wu > u, e.g., warhum > urhum Babylonian deq ("is good"). On the other hand, intervocali -m- in Late Babylonian > w or 5, e.g., Samas > tS(a)w(a)s ("th sun god" (from Aramaic transcriptions); cf. cayh for sam ("of heaven") in Seleucid Greek transcriptions; cf. Hebrew )!’ (< Simanu). Survival of the y is limited.

Morphology

Pronouns. Akkadian shows a rich range of bound and un bound pronominal forms, especially personal pronouns. I the third person, the distinctive element is s, where West Se mitic, for example, has h, e.g., su ("he"), si ("she"). Unboun pronominal forms distinguish three case forms: nominativ genitive/accusative, dative, e.g., anaku, yati, yasi ("I"), respec tively, and in bound forms genitive, dative, and accusativi e.g., beli ("my lord"), ispur-sunusim ("he sent to them"), ispui sunuti ("he sent them"), respectively where it can be seen th; in the plural at least -s- is characteristic of the dative and -t- o the accusative. The dative pronouns are a strong isogloss be tween Old Akkadian and Old Babylonian. They are restricte in Old Assyrian where the genitive-accusative forms functio as datives; dative forms appear regularly from Middle Assy ian on. There is also a possessive pronominal adjective, e.g yaum ("mine"). Of the various deixis forms, annum ("this’ and ullum ("that") can be cited, but many dialect words an forms for the near and far deixis also occur. In addition, th third person unbound pronoun can be used anaphoricall e.g., awilum su ("that man"). Interrogatives include mannum ("who") and minum ("what"), ayyum ("which [one]") and m ("what") in older dialects. The indefinite pronoun is mam man (< tman-man). A true relative pronoun is found onl in Old Akkadian: su, si, sa, fem. sat, plural sut, sat. Old As syrian has some of these forms in personal names but in later dialects they occur residually in stereotyped phrases, mostly literary. The particle sa serves as an all-purpose relative, in both nominal and verbal phrases, e.g., bitum sa redim ("the soldiers house") and sa ipusu ("which he made"). (On this see G. Deutscher, "The Akkadian Relative Clauses in Cross-Linguistic Perspective," za, 92 (2002), 86-105.) nouns and adjectives. Nouns and adjectives show structural patterning as in other Semitic languages, e.g., parrasum as an "occupational" pattern, e.g., dayyanum ("judge") or qarradum ("warrior"); and maprasum indicating instrument or place, e.g., maskanum ("depot"; cf. Barth’s Law above).

Formally, there are two genders, masculine (zero marker) and feminine (at marker). There are three numbers: singular, plural, and dual. Mimation in the singular of both genders and in the plural feminine, and nunation in the dual are regular until the end of the Old Babylonian and Old Assyrian periods. The singular is triptotically declined forming a nominative, accusative, and genitive in the earlier periods, yielding later to a binary opposition of nominative/accusative and genitive. The plural and dual are diptotic. Traces of a productive dual, nominal, and verbal, are evident in Old Akkadian but by post-Old Akkadian times it has become virtually vestigial, surviving mostly in set words and phrases.

The vocative is expressed by a stressed form with zero ending in the singular, e.g., etel (< tetel, "O, youth"), kalab (< tkalb, "O, dog"). Plural vocatives seem to coincide with the nominative forms. The morphology of the adjective differs from that of the noun uniquely in that the masculine plural exhibits the morphemes -utu(m) for the nominative and -uti(m) for the oblique cases, e.g., sarru rabutum ("the great kings"). The construct case of the noun is a short form with the case markers removed or reduced, e.g., bel bitim ("the householder"), ilsu ("his god"), marat awilim ("man’s daughter"), ilu matim ("the gods of the land"). The noun or adjective, used as a predicate, can be declined with the bound suffix personal forms, those of the first and second person showing affinity to the personal pronouns, e.g., sarraku ("I am king"), lu awilat ("be a man!"), while the third person shows gender and plural affixes only, e.g., libbasu tab ("he is satisfied"), Istar rigmam tabat ("Istar, sweet of voice"). Feminine nouns are declined in the stative without the feminine marker, e.g., gasrate malkati (< malkatum) sumuki siru ("You [Istar] are powerful, you are a princess, your names are majestic").

Prepositions and conjunctions. Prepositions govern the genitive ease of nouns, e.g, alpam kima alpim ("[he will replace] ox for ox"), and most prepositions can also function as conjunctions in which case the verb appears in the subjunctive, e.g., kima erubu ("when/as soon as he entered"). It should be noted that ina ("in"), ana ("to") and istu ("from") suppleted the common Semitic prepositions b,(‘)l, and mn respectively at a preliterate stage of Akkadian.

Other particles. Common negations are la and ul, e.g., la iddinusum ("they did not give him"), ul assat ("she is not a wife"), la kittum ("untruth"). Conjunctives are u, "and," "or," e.g., bel same u ersetim ("Lord of heaven and earth"), and the enclitic -ma used post-verbally as a sentence conjunctive, e.g., ul itarma… ul ussab ("he shall not return and take his seat [as judge]"). After nominal or pronominal forms, it forms a stressed predicate (cleft sentence), e.g., adi mati ("until when"), adi matima ("until when is it that – ?"), umma Hammurapima ("thus Hammurapi," introductory formula in letters), suma iliksu illak ("it is he who will perform the [feudal] service").

Umma, with or without the enclitic -mi, or in the Assyrian dialects ma, introduces direct speech. A strong interrogative tone can be indicated by vowel lengthening, e.g., ina bitika mannum biri anaku bariaku ("who in your household goes hungry? Should I go hungry?"). Unreal statements are indicated by the enclitic -man. Conditional sentences are introduced by summa (or summa-man for unreal conditions) with the verb in the indicative.

Adverbial constructions. In adverbial constructions the accusative is often used, e.g., imittam ("to the right"). Among the adverbial formatives are the locative-adverbial in -um/u which with nouns functions sequentially as a case, libbu/libbum = ina libbim, libbussu < -umsu ("in it"), and is used as an adverbial formative, e.g., balum ("without"). The locative terminative affixes -is in the meaning "to," e.g., asris ("to the place") and adverbially as in elis ("above," "upward").

Verbs. basic patterns. All tenses of the verb are prefixed forms: iprus ("he cut") preterite, iparras ("he cuts") present-future with characteristic doubling of the middle root radical, and, unique to Akkadian, iptaras ("he has cut / will have cut") perfect, a syntactically conditioned stressed or consequential form, e.g., dayyanum dinam idin… warkanumma dinsu iteni ("the judge passed judgment but afterward changed his verdict") or as a future perfect, e.g., inuma issanqunikkum ("When they will have reached you…"). The imperative can be derived from the preterite base, e.g., pursus ( < tprus), imperative singular (cf. below). The precative is formed by the proclitic particle lu + preterite for the third person singular and plural and i + preterite for the first person plural, e.g., lipus < lu + ipus ("let him do"), lublut <lu+ablut ("may I stay alive"), i nillik ("let us go"). Contracted forms in Assyrian differ. Other moods include the indicative in main or independent clauses having gender and plural suffixes, the subjunctive in -u (Assyrian also in -ni, also affixed to non-verbal forms) in subordinated clauses, e.g., sa ipusu ("which he did"). In Babylonia affixes of the subjunctive and ventive are mutually exclusive. Unique to Akkadian, and of a different character, is the ventive, or allative, indicating motion toward the speaker or focus of action, e.g., illik ("he came"), illikam ("he came here"). The base form participle is patterned parisum (cf. Hebrew qal active participle), while other themes (~ Hebrew binyanim) have mu- prefix forms. There is no passive participle, but the verbal adjective of each theme is a partial semantic surrogate. The verbal adjective, used in the predicative form, is declined (the stative) with bound suffix pronominal forms, as with the predicative state of nouns (cf. above). In form, then, the stative bears great resemblance to the West Semitic perfect and the old perfective in Egyptian. In meaning the stative generally indicates the resultant state indicated by the action of the verb in its finite forms, e.g., maska labis ("he is/was clothed in a skin").

Various pronominal morphemes are prefixed to the finite forms of the verb to indicate the person. The plural number is indicated in the second and third person by suffixes. Old Akkadian, Assyrian, and, less commonly, the poetic dialect distinguish the third person feminine singular while in Babylonian the masculine form serves both.

Themes (~ Hebrew binyanim). In common with other Semitic languages, semantic nuances can be given to the verb by a system of themes or forms exhibiting characteristic structures. The basic forms are commonly four in number, though rarer types can also be demonstrated. The basic verb theme is termed G (~ Hebrew qal) and contains verbs with both stative, e.g., (w)araqum ("to be/become pale") and fientive (transitive) meaning, e.g., sabatum ("to seize"). Verbs show various tense vowels between the second and third root radicals in the present-future and preterite: a – u, a – a, i – i, and u – u. The characteristic vowel of the perfect is the same as that of the present, thus iparras ("he cuts"), iptaras ("he has cut"), iprus ("he cut").

The D theme (~ Hebrew picel) is characterized by the doubling of the middle root radical and, in common with the S theme, it employs a different set of pronominal prefixes than G, and shows a characteristic a – i alternation between the tense vowel of the present and preterite. The perfect here goes with the preterite in the choice of tense vowel, thus uparras, uptar-ris, uparris. In meaning the D can be factitive, especially with stative verbs, e.g., dummuqum ("to make good"; damaqum, "to be good"); causative, e.g., lummudu ("to teach"; lamadu, "to learn"); estimative, e.g., q/gullulu ("to treat disparagingly"; qalalu, "to be/become insufficient"); iterative, e.g, sullum ("to pray"), qu’um ("to wait"). The D also serves as a denominating theme, e.g., sullulu ("to roof over"; sululu, "roof") and more rarely indicates plurality of object, or subject.

The S theme (Hebrew hiphil) is so termed after the -s(a)-morpheme placed before the first root radical. Thus, usapras, ustapris, usapris have the same tense vowel alternation as in D and of the nuances conveyed by this theme the main one is causative, e.g., susum ("to bring out"; wasum, "to go out"). An internal S indicates entry into a state or condition of some duration, e.g., sulburum ("to grow old"), sumsum ("to spend the night").

In the N theme, an n(a) morpheme is placed before the first root radical. Like in the G theme, various tense vowels are shown, and these can be correlated with those of the G.

For parasum, the forms are ipparras (< tinparras), ittapras (< tintapras), ipparis (< tinparis). The Ntheme is commonly a passive to the G, e.g., napsurum ("to be untied, absolved, explained"). Other nuances are reflexive, e.g., nalbusum ("to get dressed") and related middle meanings, e.g., naplusum ("to look [benignly] upon"). Stative verbs take on an ingres-sive meaning, e.g., nabsum ("to come into being"; basum, "to be").

Within each theme occur forms with -ta and tan/tana-infixes. The t forms (Gt, Dt, St, Nt) with the – ta- infixes give a reciprocal or separative meaning, e.g., imtalku (["the judges] consulted together"), ittalak ("he went off"). Some t forms coincide with perfect forms making the latter difficult to recognize. The tn forms (Gtn, Dtn, Stn, Ntn) with a -tan/tana- infix give a durative or iterative force, e.g., ittanallak ("he walks around/back and forth"), imtanaqqutu ("[the stars] fall down [from heaven]").

Akkadian lacks a developed series of parallel passive themes. The G theme shows no trace of such related forms. Here the N theme serves as passive. In the D theme, some t forms, identical with other t forms of the D theme, have a passive or middle nuance, e.g., utellulum ("to become clean, cleanse oneself"; elelum, "to be clean"; ullulum, "to cleanse"), eleppam uttebbe usa libbisa uhtalliq ("he subsequently sank the boat and thereby caused the loss of its cargo") as against matt… uhtalliq ("my country has been destroyed"). Likewise, in the S theme, t forms can have a passive or middle meaning. Compare seam kt masi tustaddin (perfect; "how much grain have you brought in?") and se’um sa ustaddinu ("grain which was brought in"). These t forms are termed Sti in distinction to a rarer non-passive t form, St2, which has a unique present, e.g., la tustallapat ("you are not to touch").

Weak verbs. There are several classes of "weak" verbs. Primae Aleph has two groups, those without apophony, e.g., akalum ("to eat"), and those with, e.g, epesum ("to do"). The vowel coloring is generally a function of the underlying la-ryngeal, although some forms show a strong aleph. The basic phonological change here is that v > v"; thus, tipus preterite (pattern iprus) > tpus ("he made"), and similarly throughout the paradigm. Mediae Aleph also have "a" and "e" classes. They further differentiate in a strong aleph group, e.g., isal ("he asked") and a a/e group which decline like vocalic roots (see below), but crossovers are not uncommon. Primae Nun is characterized by the assimilation of the N root element to a following consonant, e.g., iddin < tindin ("he gave"). In Primae Waw initial or intervocalic w goes to 5 or m in post-Old Babylonian times, e.g., waladum > aladum ("to give birth"). In fientive verbs vw > uw > u, e.g., tiwsib > uwsib > usib ("he sat"). Statives behave like Primae Yod, e.g., tqer (not uqer < tiwqer; note that the occurrence of the initial or final y is very restricted in historic Akkadian and these verbs generally behave like Primae Aleph with the apophony of a >e). Both fientive and stative verbs have Primae Yod type S forms, e.g., usesib ("he seated" as if < tusaysib), ususib type forms (< usawstb) occurring only rarely in poetic dialect (but note Neo-Assyr-ian ittusib, Babylonian ittasab ("he sat")).

Vocalic roots ("hollow verbs" Mediae Waw/Yod) are of the pattern CvC, where the middle radical has to be considered as a long vowel: u, i, a, or e (secondary). In the G present-future and in the present-future and preterite of the D, the suffixing of vocalic morphemes induces reduction of the theme vowel – middle root radical and gemination of the third root radical, e.g., ikan ("he is upright"), ikunnu ("they are upright"). In Assyrian uncontracted forms are usual, thus ikuan. The last major division of weak verbs is the Tertiae Infirmae. These are final -u, e.g., ihdu ("he was happy"); final -i, iqbi ("he spoke"); final -a, ikla ("he withheld"); and final -e, isme ("he heard"). These vowels are anceps and are long when followed by bound morphemes, e.g., iqbi, but iqbisum ("he told him"). Two main groups of quadrilateral verbs occur of the type C1 C2 C3 C4 in the S and N themes, e.g., nabalkutum ("to jump over"), subalkutum ("to cause to jump over, overturn"), including a weak class, e.g, naparku ("to be idle, unemployed"). A third type is of the pattern S C1 C2 C2 where C2 is l or r, e.g., suharrurum ("to be deathly still").

It should be noted that the normal position of the Akkadian verb in the sentence is at the end (unlike its nearest Semitic relatives) and this is most likely due to the influence of Sumerian, where the verb is similarly placed.

AKKUM

(Heb ![]() , abbreviation consisting of the initial letters of

, abbreviation consisting of the initial letters of ![]() ("worship of stars and planets") or

("worship of stars and planets") or ![]() ("worshipers of stars and planets"). It was originally applied to the Chaldean star worshipers but it was later extended to apply to all idolaters and forms of idolatry. This word is not found at all in the oldest editions of the Mishnah, Talmud, the Yad of Maimonides, or the Shulhan Arukh. Most editions of these works have a note to the effect that the laws against Akkum refer only to ancient idolaters and not to Christians.

("worshipers of stars and planets"). It was originally applied to the Chaldean star worshipers but it was later extended to apply to all idolaters and forms of idolatry. This word is not found at all in the oldest editions of the Mishnah, Talmud, the Yad of Maimonides, or the Shulhan Arukh. Most editions of these works have a note to the effect that the laws against Akkum refer only to ancient idolaters and not to Christians.

Professed Judaism in secret. Aklar, who was born in *Meshed, Persia, was known as a Muslim by the name of "Mulla Mu-rad." Aklar succeeded his father as the secret rabbi of the anusim community in Meshed. He immigrated to Jerusalem in 1927 and there continued to serve as the spiritual leader of the Meshed and Bukharian communities. His Judeo-Persian renderings of liturgical works, translated in Jerusalem, are a major contribution to this literature. They include Avodat ha-Tamid (1908), Olat Shabbat (1910), Selih ot (1927), Piyyutim for the Holidays (1928), and the Passover Haggadah (1930). In his Judeo-Persian prayer book he incorporated a Hebrew poem by Solomon b. Mashi’ah, describing the tragic events which led to the forced conversion of the community in Meshed in 1839. His unfinished manuscripts include translations from the writings of Maimonides, and Saadiah Gaon, of the azharot of Solomon ibn Gabirol, parts of the Koran, and memoirs.

AKNIN, JOSEPH BEN JUDAH BEN JACOB IBN

(c. 11501220), philosopher and poet. Aknin was born in Barcelona, Spain. Probably as a result of the Almohad persecutions, he, or perhaps his father, moved to North Africa, presumably Fez, Morocco. He remained there until his death, not withstanding his ardent wish to go elsewhere so that he could practice Judaism openly. That he felt guilty about living as a Crypto-Jew is evident from a discussion in which he passed harsh judgment on forced converts. He and Maimonides met each other during the latter’s sojourn in Fez and Aknin wrote a sad couplet on the sage’s departure for Egypt. However, he must not be identified or confused with Joseph b. Judah ibn *Shimon, a disciple of Maimonides, who eventually was wrongly called "ibn Aknin." Little else is known of Aknin’s life. He may have been a physician by profession – he certainly was adept in the subject. Nothing is known of his family life or descendants.

Aknin is the author of a number of works:

(1) Sefer Hlukkim u-Mishpatim, no longer extant, was a book of laws divided into treatises, the first of which dealt with doctrines and beliefs. It may have been modeled on Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah, although, unlike this work, it limited itself to laws still practiced by the Jews of the time. He spoke of it as "my major work."

(2) Risalat al-ibanah fi usul al-diyanah ("Clarification of the Fundamentals of Faith") is also no longer extant. Nevertheless, it is known from a passage cited in another work that this work engaged in a discussion of man’s freedom.

(3) Ma’amar al ha-Middot ve-ha-Mishkalot is an anonymous medieval Hebrew translation of an Arabic work by Aknin, entitled maqala le-Rabbenu Yehosef ben Aknin Zal fimari fat Kammiyyab al-maqadir al-madhkurafi Torah she-bi-khetav ve-Torah she-beal peh. The Arabic original is extant in manuscript in the Bodleian Library (Ms. Poc. 186; cf. Steinschneider, Arab Lit, 230-1); the Hebrew translation of the work was published in Ginzei Nistarot (ed. by J. Kobak, 3 (1872), 185-200). The introduction states: "It is my purpose to gather all that is scattered in [the] Mishnah and Talmud on coins, weights, measurements, boundaries, and time, and compare it with present-day standards."

(4) Mevo ha-Talmud, written in Hebrew and divided into 12 topics, concerns "principles which a person must know if he desires to become skilled in talmudic lore." It was published under the title Einleitung in den Talmud with an introduction by H. Graetz in Festschrift… Zacharias *Frankel (Breslau, 1871; repr. 1967).

(5) TTibb al-Nufus al-Sallma wa-Mualajat al-Nufus al-Allma ("The Hygiene of Healthy Souls and the Therapy of Ailing Souls") is an ethical compilation written in Arabic. After a lengthy introductory topic, in which Aknin offers his views on the composition of the soul and the functions of its three parts, and in which he explains his beliefs regarding the afterlife of both the righteous and the wicked, he turns to an examination of such themes as speech and silence, keeping a secret, filial piety, food and drink, the true goods in life, and so forth. He urges moderation in all areas with a clear suggestion of the futility of material self-indulgence and the gain of spiritual and religious pursuit. Every section opens with a statement of the right course, supported by rabbinic references and followed in many instances by epigrams and sayings culled from classical and Arabic studies.Until the age of 30, the student should be concerned with traditional Jewish lore, which he should master to such a degree that he will be able to hold his ground when apparent difficulties and challenges seem to impugn the validity of tradition. The rest of his life should be devoted to the cultivation of logic, music, mathematics, mechanics, and metaphysics. This topic was published in its Arabic original and a German translation by M. Guedemann, in his Das judische Un-terrichtswesen waehrend der spanisch arabischen Periode and in Hebrew by S. Epstein, in: Sefer ha-Yovel… N. Sokolow (1904, pp. 371-88).

(6) Sefer ha-Musar, written in Hebrew, is a commentary on the mishnaic tractate Pirkei Avot. In it Aknin follows Maimonides’ commentary on this tract, and although he does not follow it slavishly, the latter’s influence is obvious. Interested in psychology and ethics, he dwells particularly on statements that deal with conduct, beliefs, and dispositions. He often develops as part of his exposition lengthy discussions on the constitution of the soul, man’s responsibility for his actions, miracles in a world governed by natural laws, creation, and other metaphysical issues. The work was edited by W. Bacher as Sefer Musar (1910).

(7) Inkishaf al-asrar wa-tuhur al-anwar ("The Divul-gence of Mysteries and the Appearance of Lights") is a commentary in Arabic on the Song of Songs. The work starts from the premise that it would be preposterous to believe that the wise King Solomon would compose a love story or indulge in erotic banter: the book bears such an external character simply as a pedagogic expedient to attract the young. According to his interpretation, the Song of Songs is a description of the mutual craving of the rational soul and the active intellect and the obstacles in the path of their union. Aknin boasts that no one preceded him in this approach to an interpretation of the Song of Songs. In fact, although Maimonides plainly offered a general explanation of the book along these lines, Aknin was the first to work out the theme in detail in a complete commentary. In his commentary he offers a tripartite explanation of each verse: first, what he calls the exoteric sense, that is, an explanation of the grammatical forms and of the plain meaning, but he avoids the introduction of the erotic aspect; second, what he calls the rabbinic interpretation, an explanation concerned with the fate of Israel, its tragedy, and its hopes (this is the most widely accepted allegorical interpretation, which is drawn from various literary compilations, mainly Midrashim on the Song of Songs); and third, the endowment of each word in the verse under discussion with implications of physiology, psychology, logic, and philosophy, which Aknin consistently opens with the phrase "and according to my conception." This work was edited and translated into Hebrew by A.S. Halkin as Hitgallut ha-Sodot ve-Hofa’at ha-Meorot (1964).

Aknin is typical of a group of intellectuals in the Jewish community under Islam that was impressed with the learning and doctrines of Greek and Hindu origin cultivated by Muslim intellectuals. However, he saw no conflict between his religious and secular learning. He was certain of the validity of his Jewish beliefs and way of life, and he was convinced that the ultimate goals of his Jewish and secular learning were identical. Aknin did not leave a mark on his peers in his or later generations, and his influence, evidently, was very limited.

AKRA

Town in Iraqi Kurdistan, known as Ekron among Jews. There was an ancient Jewish community in Akra. In the 19th century between 300 and 500 Jews seem to have been living there. According to the official census of 1930, about 1,000 persons of a total population of approximately 19,000 were Jews. They spoke Aramaic-Jebelic and were engaged in agriculture, whitewashing, goldsmithery, the perfume trade, and in commerce generally. Many of the orchards of the district belonged to Jews. The community was centered around its synagogue. In 1950 the Jews were attacked by their Kurdish neighbors and many of them were injured; after this incident they immigrated to Israel.

AKRISH, ISAAC BEN ABRAHAM

(b. 1530), talmudic scholar, traveler.Son of a Spanish exile, who went to Salonika after having lived in Naples, Akrish, despite his lameness, traveled extensively throughout his life. His special interest was in manuscripts which he attempted to save from destruction. Arriving in Egypt about 1548, he was engaged by *David b. Solomon ibn Abi Zimra, the head of Egyptian Jewry, to teach his grandchildren. Whatever he earned he spent in purchasing manuscripts, and devoted his time to copying those in Ibn Zimra’s library. In 1554, on his way to Candia, his books were confiscated by the Venetian authorities in the wake of the recent edict against the Talmud. Succeeding in rescuing his books, he apparently traveled to Constantinople and then in 1562 back to Egypt. Later he returned to Constantinople where patrons such as Don Joseph *Nasi and Esther *Kiera helped him to engage scribes to copy manuscripts. In 1569 a fire destroyed most of his books. He left Constantinople for Kastoria where he lived for four years in poverty.

Akrish then began publishing books and documents he had collected during his travels. Three such collections, which are of great importance, were published in Constantinople between 1575 and 1578 without title pages or specific titles. The first (republ. as Kovez Vikkuhim, 1844) contained Iggeret Ogeret, a collection of polemical writings, including Profiat *Duran’s famous letter, Al Tehi ka-Avotekha, the polemical letter of Shem Tov ibn *Falaquera, and Kunteres Hibbut ha-Kever by Akrish himself. The second collection (16073) contains several important items about the Ten Lost Tribes, the letter of *Hisdai ibn Shaprut to the king of the *Kha-zars, and Ma’aseh Beit David bi-Ymei Malkhut Paras, which is the story of *Bustanai. The Khazar correspondence was published by Akrish to "strengthen the people in order that they should believe firmly that the Jews have a kingdom and dominion."

The third collection of three commentaries on the Song of Songs by *Saadiah, Joseph ibn Caspi, and an unknown author, possibly Jacob Provencal, were annotated and corrected by Akrish himself. He also wrote Heshbon ha-Adam im Kono (published with Kunteres Hibbut ha-Kever in Sar Shalom by Shalom b. Shemariah ha-Sephardi, Mantua, 1560?).

AKRON

Industrial city in northeast Ohio. Akron is Ohio’s fifth largest city, with a population of 217,074 (2000 census). German Jewish merchants settled in Akron prior to the Civil War, but the first congregation, the American Hebrew Association – known today as Temple Israel (Reform) – was founded in 1865. The community grew slowly until it received an influx of settlers from Eastern Europe in the 1880s. Engaging in the clothing business, cigar making, and other small businesses, the Jewish population reached a peak of 7,500 in the 1930s. In 2005, there were approximately 3,500 Jews in Akron and its suburbs with five congregations: Anshe Sfard/Re-vere Road (Orthodox, founded 1915), Chabad of Akron (Orthodox, 1986), Beth El Congregation (Conservative, 1946), Temple Beth Shalom (Reform, 1977), and Temple Israel (Reform, 1965). The Jewish Community Board of Akron, founded in 1935 as the Federation of Jewish Charities, announced in 2004 that its director would also lead the Jewish Federation of Canton, Ohio, a neighboring city with a Jewish population of approximately 1,200. The Jewish Community Board offers support to the Shaw Jewish Community Center, the Jewish Family Service, the Jerome Lippman Day School, and the Akron Jewish News. It also provides funding for campus services to Kent State University, the University of Akron, and Hiram College. Noted Akron residents were Judith A. *Resnik (1949-1986), a nasa astronaut who perished in the explosion of the orbiter Challenger, and Jerome Lippman (1913-2005) who invented a heavy-duty waterless hand soap during World War 11.