AHIJAH

(Heb ![]() "my [or the] brother is yhwh"), son of *Ahitub, priest of the house of Eli (i Sam. 14:3). Ahijah was apparently the chief priest in Shiloh during the reign of Saul (cf. Jos., Ant., 4:107), although his name does not appear in the list of chief priests in i Chronicles 6:50-55 and in Ezra 7:2-5. Several scholars identify Ahijah with *Ahimelech, son of Ahitub, who served as priest of Nob in Saul’s days, assuming that the name Ahijah is the short form of Ahimelech or that the element melekh ("King") in his name was replaced by the divine name.

"my [or the] brother is yhwh"), son of *Ahitub, priest of the house of Eli (i Sam. 14:3). Ahijah was apparently the chief priest in Shiloh during the reign of Saul (cf. Jos., Ant., 4:107), although his name does not appear in the list of chief priests in i Chronicles 6:50-55 and in Ezra 7:2-5. Several scholars identify Ahijah with *Ahimelech, son of Ahitub, who served as priest of Nob in Saul’s days, assuming that the name Ahijah is the short form of Ahimelech or that the element melekh ("King") in his name was replaced by the divine name.

When Saul fought against the Philistines at Michmas, Ahijah wore an ephod (i Sam. 14:3). According to i Samuel 14:18, Ahijah served before the Ark of God; however, according to the same topic, verse 3 (and also according to the lxx; Baraita di-Melekhet ha-Mishkan, 6 [and cf. Ish Shalom's ed., p. 44]; Ibn Ezra’s commentary to Ex. 28:6 – all referring to i Sam. 14:18), "ephod" is to be read (instead of "ark"). Furthermore, only the ephod (and not the ark) is mentioned in the Bible as having been used for consulting the divine will (cf. the consultation by means of the ephod in i Sam. 23:9; 30:7). Ahijah may also have been the priest who inquired of God first whether to advance against the Philistines and then, upon failing to obtain a response, provoked God’s displeasure (i Sam. 14:36 ff.).

AHIJAH THE SHILONITE

(Heb. ![]() , Israelite prophet during the latter part of Solomon’s reign and during the concurrent reigns of *Rehoboam and *Jeroboam. Jeroboam son of Nebat of Zeredah (which, according to the Sep-tuagint, i Kings 12:24, was near Shiloh), enjoyed the support of Ahijah, whose main antagonism against Solomon was due to the tolerance shown by the king to foreign cults. At a secret meeting with Jeroboam outside Jerusalem he tore Jeroboam’s new garment (or his own – the text is ambiguous) into 12 pieces as a symbol of the 12 tribes and gave him ten. The kingdom of Israel would be divided; only one other tribe (Benjamin), beside Judah, would remain loyal to the House of David (ibid. 11:29-39). Not improbably, Ahijah expected Jeroboam to restore the ancient central sanctuary of his native Shiloh. When Jeroboam, instead, set up golden calves in sanctuaries at Beth-El and Dan, the estrangement between him and Ahijah became inevitable. When Jeroboam’s son Abijah fell ill, the king who no longer dared to face the old seer, by now almost blind, sent his wife in disguise to inquire about the child’s fate. He not only foretold her son’s death but predicted a dire end for the House of Jeroboam (ibid. 14:1-18).

, Israelite prophet during the latter part of Solomon’s reign and during the concurrent reigns of *Rehoboam and *Jeroboam. Jeroboam son of Nebat of Zeredah (which, according to the Sep-tuagint, i Kings 12:24, was near Shiloh), enjoyed the support of Ahijah, whose main antagonism against Solomon was due to the tolerance shown by the king to foreign cults. At a secret meeting with Jeroboam outside Jerusalem he tore Jeroboam’s new garment (or his own – the text is ambiguous) into 12 pieces as a symbol of the 12 tribes and gave him ten. The kingdom of Israel would be divided; only one other tribe (Benjamin), beside Judah, would remain loyal to the House of David (ibid. 11:29-39). Not improbably, Ahijah expected Jeroboam to restore the ancient central sanctuary of his native Shiloh. When Jeroboam, instead, set up golden calves in sanctuaries at Beth-El and Dan, the estrangement between him and Ahijah became inevitable. When Jeroboam’s son Abijah fell ill, the king who no longer dared to face the old seer, by now almost blind, sent his wife in disguise to inquire about the child’s fate. He not only foretold her son’s death but predicted a dire end for the House of Jeroboam (ibid. 14:1-18).

In ii Chronicles 9:29 Ahijah, in accordance with the Chronicler’s practice, is cited, along with the other two prophets who were active in the reign of Solomon, as an author of the books of Kings’ account of Solomon’s reign.

In rabbinic tradition, Ahijah was a Levite at Shiloh. He was the sixth of seven men whose lifetimes following one another encompass all time (bb 121b) and is given a life span of more than 500 years. (On this basis Maimonides, in the introduction to his Code, makes him an important link in the early tradition of the Oral Law.) Ahijah was reputed to be a great master of the secret lore (Kabbalah), and h asidic legend makes him a teacher of *Israel Ba’al Shem Tov. He is said to have died a martyr’s death at the hands of Abijah, son of Re-hoboam and king of Judah.

AHIKAM

(Heb. ![]() battle]"), son of *Shaphan and father of *Gedaliah, a high royal official. Ahikam was one of the men sent by King Josiah to the prophetess *Huldah (ii Kings 22:12, 14; ii Chron. 34:20). Later, during the reign of Jehoiakim, when Jeremiah prophesied the destruction of Jerusalem, Ahikam used his influence to protect Jeremiah from death (Jer. 26:24).

battle]"), son of *Shaphan and father of *Gedaliah, a high royal official. Ahikam was one of the men sent by King Josiah to the prophetess *Huldah (ii Kings 22:12, 14; ii Chron. 34:20). Later, during the reign of Jehoiakim, when Jeremiah prophesied the destruction of Jerusalem, Ahikam used his influence to protect Jeremiah from death (Jer. 26:24).

Ahikam was a member of one of the most influential pro-Babylonian families in the last days of the Judean Kingdom. Shaphan, his father, was the scribe of Josiah (ii Kings 22:3ff. et al.); his brother Elasah was one of the men sent to Babylon by Zedekiah who brought the letter written by Jeremiah to the elders in exile (Jer. 29:1-3); his brother *Jaazaniah is mentioned in Ezekiel 8:11 among the elders of Jerusalem; and his son Gedaliah was appointed governor of Judah after the destruction of Jerusalem (Jer. 40:5-6). A seal impression published recently appears to bear his name.

AHIKAR, BOOK OF

A folk work, apparently already widespread in Aramaic-speaking lands during the period of Assyrian rule. It was evidently well-known among the Jewish colonists in southern Egypt during the fifth century b.c.e. and at the beginning of the twentieth century the major part of an Aramaic text of the work was discovered among the documents of the Jewish community of *Elephantine. Greek writers were likewise acquainted with its contents. The book has survived in several versions: Syriac, Arabic, Ethiopic, Armenian, Turkish, and Slavonic. These texts bear a fundamental similarity to the ancient Elephantine version. It may be subdivided into two parts: (1) the life of *Ahikar; (2) the sayings uttered for the benefit of Nadan, his adopted son.

Ahikar the Wise, the hero of the work, is mentioned in the apocryphal book of Tobit as one of the exiles of the Ten Tribes. He purportedly attained high rank, being appointed chief cupbearer, keeper of the royal signet, and chief administrator during the reigns of Sennacherib and Esarhaddon. In his later years, realizing that he would leave no offspring, he adopted his sister’s son Nadan and groomed him for a high office at court. Ahikar’s instructions to Nadan in preparation for this position are couched in the form of epigrams. Ahikar, however, ultimately convinced that his protege was not equal to the task, disowned him. Nadan thereupon slandered Ahi-kar before the king. When this accusation was proved false, Nadan was handed over to Ahikar who imprisoned him near the gateway to his home. Thereafter, whenever Ahikar passed by this place, he uttered words of reproof to his former adopted son. These remarks, presented as aphorisms, comprise the last section of the Book of Ahikar. Both the contents and aim of the work indicate its Aramean-Assyrian milieu. In textual format, it resembles Job, which also contains not only wisdom sayings, but also events associated with the hero of the tale. Also similar to Ahikar is Proverbs 31:1: "The words of King Lemuel"; which, though presently comprising only the apothegmatic section, may well originally have contained biographical data concerning Lemuel. Works along these lines were not unknown among the peoples of antiquity and in Israel too, the Wisdom literature did not fail to take ideas from non-Israelite sources. However, the Book of Ahikar, despite its dissemination and popularity among the Jews, left no imprint upon Hebrew literature. The reason may be that its many pagan features remain unblurred, even in late editions belonging to the Christian era. A profounder cause, however, is the fact that a spirit of total submissiveness to and awe of human rulers pervades the work to such an extent that their edicts and promulgations are regarded as inviolable law. This note of self-negation before a king of flesh and blood, which is of the very essence of the work, was entirely alien to the Jewish spirit.

Ahikar

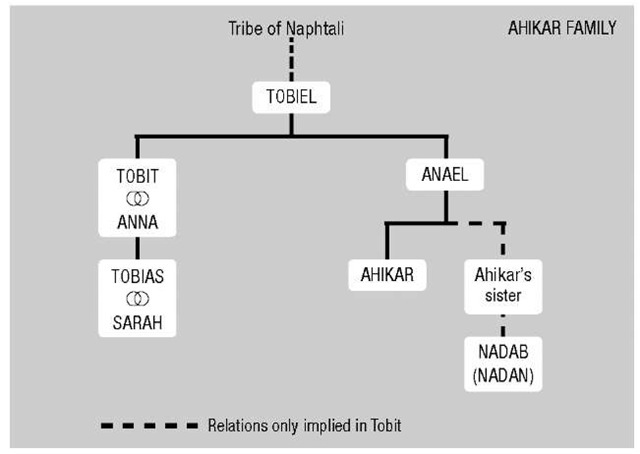

Although the Book of Ahikar did not exert any direct influence on Jewish literature, Ahikar himself was assimilated in Jewish sources.According to 1:21-22, Ahikar is Tobias’ cousin, son of Tobit’s brother Anael.

The Jews made this hero of the pagan Wisdom tale into a pious Jew of the tribe of Naphtali, an instance of how they adopted and reused international Wisdom traditions. The transformation of Ahikar into an exiled Israelite was accompanied, in Tobit 14:10, by emphasis on the vindication of righteousness in the relationship between Ahikar and Nadab. Ahikar was also mentioned in Hellenistic literature and in a variety of later sources. Ahikar is now known from Babylonian sources as the court sage in the time of King Sennacherib.

AHIMAAZ

(Heb. ![]() selor^]"), name of three biblical personalities.

selor^]"), name of three biblical personalities.

(1) Father-in-law of King Saul (1 Sam. 14:50).

(2) Son of the priest *Zadok. When David fled Jerusalem because of the revolt of *Absalom, Ahimaaz, together with Jonathan, the son of David’s other priest Abiathar, remained just outside the city. A messenger of their fathers delivered information about the rebels’ plans to them, which they conveyed to David (11 Sam. 15:27-36; 17:15-22). Later, being a swift runner, he overtook and passed the messenger who was to report the outcome of the battle with Absalom to David. He thus reported the defeat of the rebels, but left to the messenger the unenviable task of informing the king that Absalom had been killed (ibid. 18:19-32).

(3) A son-in-law of Solomon, his prefect over the district of Naphtali (1 Kings 4:15). Some identify him with Ahimaaz the son of Zadok (above). If that conjecture is correct, it is likely that his prefectship was bestowed on him because he was debarred from the priesthood, possibly because of a defect acquired in combat. According to 1 Chronicles 5:34-36, Azariah the great-grandson of Ahimaaz succeeded Zadok as a priest in Solomon’s Temple, but it seems that the verses are corrupt and this Azariah is Ahimaaz’ son. The name Ahimaaz probably also appears on a signet ring discovered at Tell Zakariyeh (ancient Azekah). It has not been satisfactorily explained. The name Maaz occurs in 1 Chronicles 2:27.

AHIMAAZ BEN PALTIEL

(b. 1017), chronicler and poet of Capua, south Italy. In 1054 when he removed to Oria, the place of origin of his family, he compiled Megillat Yuhasin ("The Scroll of Genealogies"), also known as Megillat Ahimaaz ("The Ahimaaz Scroll" or the "Chronicle of Ahimaaz"). It describes in rhymed prose the genealogy of his family from the ninth century to his own time. The Ahimaaz family counted among its members prominent personalities, who had been leaders of their generations in the different communities of Italy, as well as in North Africa, e.g., Shephatiah, Amittai b. Shephatiah, Paltiel. They actively participated in some of the most important events in these countries. Megillat Ah imaaz is consequently a significant Jewish historical source covering several periods and countries. Apart from historical data, it includes legends and fantastic tales and, despite some inaccuracies, it is a reliable historical document. The one known manuscript is in the library of Toledo Cathedral, where it was discovered by A. Neubauer in 1895. It has since been edited several times; the edition by B. Klar appeared in 1944 (second edition, M. Spitzer, 1974). Ahimaaz also composed a poem in honor of the nagid *Paltiel (included in the Scroll) and a number of piyyutim. A photograph of the manuscript was published in 1964 in Jerusalem. In 1965, the text of the manuscript was published with a concordance: Megillat Ah imaaz Me’ubbedet u-Muggeshet ke-Homer le-Millon, edited by R. Mir-kin with the assistance of I. Yeivin and G.B. Tsarfati. There is an English translation by M. Salzman (1924, 1966) and an Italian one by C. Colafemmina (2001).

AHIMAN, SHESHAI, TALMAI

The sons of *Anak, who were said to have inhabited *Hebron when the spies sent by Moses reconnoitered Canaan (Num. 13:22). Their names have not been identified with certainty. Ahiman may be Semitic, while Kempinsky and Hess regard Sheshai and Talmai as Hur-rian. The sons of Anak are described as *Nephilim (ibid. 13:33), a term probably indicating extraordinary stature and power (cf. Gen. 6:4). In Deuteronomy 2:21 (cf. Deut. 1:28) the Ana-kim are described as "great, numerous, and tall." Traditions about an ancient giant race were apparently current in Israel, Amon, and Moab (see *Og, *Rephaim).

According to Joshua 15:13-14, *Caleb attacked Ahiman, Sheshai, and Talmai and dispossessed them (cf. Judg. 1:20). Another passage credits the tribe of Judah with the victory over the three brothers (Judg. 1:10). Finally, according to Joshua 11:21-22, Joshua annihilated the Anakites. The name Ahiman occurs as well in 1 Chronicles 9:17 and in three epigraphs: a jug from *Elephantine, one seal from Megiddo, and another of unknown provenance. Talmai is also the name of a king of Geshur in northern Transjordan who was a contemporary of David.

AHIMEIR, ABBA

(pseud. of Abba Shaul Heisinovitch; 1898-1962), journalist and writer, Revisionist leader in Palestine. Ahimeir was born in Dolgi near Bobruisk, Belorussia, studied at the Herzlia High School in Tel Aviv (1912-14) and returned to Russia where he became a member of *Z e’irei Zion. After World War 1 he studied history at the universities of Liege and Vienna. On his return to Palestine in 1924, he joined *Ha-Po’el ha-Z a’ir, but his views gradually underwent a change to extreme opposition to both communism and socialism. In 1928 he joined the ^Revisionists and advocated active opposition to the Mandatory government. He was the first to organize illegal public action in Palestine, and as a result was arrested several times from 1930 onward. When Chaim *Arlosoroff was murdered in June 1933, Ahimeir was accused of plotting the murder, an accusation which he vehemently denied. After spending a year in prison, he was cleared by a court of appeals before defense witnesses had been called. He was nevertheless detained in prison, charged with organizing Berit ha-Biryonim, an underground group formed for the purpose of fighting British policy in Palestine, and sentenced to a further 18 months’ imprisonment. Ahimeir’s views contributed to the ideological basis of the *Irgun Z eva’i Le’ummi and *Lohamei H erut Israel underground movements. He wrote numerous articles, many of them violently polemical. His impressions of prison life appeared as a book, with the punning title Reportazhah shel Bahur "Yeshivah" ("Report by an Inmate," 1946). His views on the problems of Judaism and Zionism are set down in Im Keriat ha-Gever ("When the Cock Crows," 1958) and Judaica (Heb., 1961). After Ahimeir’s death a committee was formed to publish his works under the title Ketavim Nivharim ("Selected Works").

AHIMELECH

(Heb. ![]() "[the divine] brother is king" or "the Melech [deity] is my brother"), name of three biblical figures.

"[the divine] brother is king" or "the Melech [deity] is my brother"), name of three biblical figures.

(1) Ahimelech, son of Ahitub, was a member of the priestly family of *Eli, who served in the Temple of *Nob (1 Sam. 21-22). Ahimelech has been identified with *Ahijah, son of Ahitub, who is also mentioned in the time of Saul and who acted as a priest in Saul’s war with the Philistines (14:3, 18). Ahimelech probably founded the Temple of Nob after the destruction of *Shiloh by the Philistines in the time of Samuel. He served as the high priest in Nob, and "85 persons that wear linen ephods" were under his charge (22:16-18).

When David escaped from Saul, he first came to Nob where Ahimelech provided him with bread and with the sword of Goliath, which was kept in the Temple (21:1-10, 22:10-15). *Doeg the Edomite informed Saul about it and stated that Ahimelech "inquired of the Lord" for David (22:10), for which Ahimelech (22:15) excused himself by pointing out that it was not the first time, for he had always understood that David was Saul’s trusted revenger. Saul, however, put to death Ahimelech and the rest of the priests of Nob. One son of Ahimelech, *Abiathar, escaped and joined David.

(2) Ahimelech, son of Abiathar, was probably the grandson of the former. He is mentioned as a priest, together with Z adok, son of Ahitub, in one of the lists of David’s officials (ii Sam. 8:17). In a parallel list he is called Abimelech (1 Chron. 18:16; possibly a scribal error, as testified by some Mss. of the mt, as well as by the Vulg.). In the lists of David’s officials in ii Samuel 20:25, and i Chronicles 26:24, as well as in the historical narratives, only Abiathar and Zadok are mentioned as high priests. Therefore, scholars doubted the historicity of Ahimelech and emended the text in ii Samuel 8:17 to read "Z adok and Abiathar son of Ahimelech son of Ahitub."

(3) Ahimelech the Hittite was one of the men who joined David when David fled from Saul (i Sam. 26:6). He was probably one of David’s warriors, as he is mentioned with *Abishai b. Zeruiah. Ahimelech was only one of many foreigners who attached themselves to David, although most of the others joined David after he was made king.

In the Aggadah

Ahimelech would not allow David to partake of the sanctified shewbread, until David pleaded that he was in danger of starvation (Men. 95b). The dispute between Ahimelech and Saul (i Sam. 22:12-19) was based on Ahimelech’s action in consulting the Urim and Thummim on David’s behalf. Saul maintained that it was a capital offense, since it was a privilege reserved for the king, while Ahimelech maintained that, when affairs of state were involved, the privilege was a universal one, and certainly applied to David, in his position as a general of the army. Abner and Amasa supported Ahimelech’s argument, but Doeg did not, and Saul therefore placed upon him the task of killing Ahimelech (Yal. 131).

Ahithophel, realizing that the respite afforded to David would be fatal to Absalom and his supporters, returned home and committed suicide (17:23).

A juxtaposition of ii Samuel 11:3 and 23:34 suggests that Bath-Sheba, the wife of Uriah, whom David debauched, was a granddaughter of Ahithophel. This act of David could thus be the motive for Ahithophel’s defection (cf. Sanh. 101b).

The meaning of the name is doubtful. It may be a theo-phoric combination, the ophel ("folly") being a pejorative substitute for the name of a Canaanite god (see *Euphemism); but in Deuteronomy 1:1, it is the name of a place (Tophel).

In the Aggadah

The rabbis rank Ahithophel and Balaam as the two greatest sages, the former of Israel and the latter of the Gentiles. Both, however, died in dishonor because of their lack of humility and of gratitude to God for the divine gift of wisdom (Num. R. 22:7). Ahithophel’s inciting of Absalom to rebel against his father, King David, was in order to gain the throne himself, since he mistakenly regarded prophecies of royal destiny concerning his granddaughter, Bath-Sheba, to apply to himself (Sanh. 101b). The name of "Ahithophel" is interpreted as "brother of prayer" (Heb. ahi tefillah), referring to the fact that he composed three new prayers daily (tj Ber. 4:3, 8a). Socrates was said to have been his disciple (Moses Isserles, Torat ha-Olah 1:11, quoting an old source). He was 33 years old when he took his life, and he was one of those who have no share in the world to come (Sanh. 10:2).

AHITHOPHEL

(Heb ![]() THE GILONITE (i.e., of the Judean town of Giloh), adviser of King *David (ii Sam. 15:12; i Chron. 27:33-34): "Now, in those days, advice from Ahitho-phel was like an oracle from God" (ii Sam. 16:23). Ahithophel was the only one of David’s inner council who joined *Absalom in his revolt against his father (15:12). His defection was a source of great anxiety to David (15:31), and prompted him to charge *Hushai the Archite with counteracting Ahithophel’s counsel (15:34; 16:15ft.). On Ahithophel’s advice Absalom took possession of David’s concubines, thus demonstrating that the breach between him and his father was final (16:21). Ahithophel further proposed that he himself should pick 12,000 men and pursue David so as to overwhelm him at the nadir of his strength (17:1-3). Hushai, however, persuaded Absalom to muster a vast army before attempting to battle with such formidable adversaries as David and his professional warriors.

THE GILONITE (i.e., of the Judean town of Giloh), adviser of King *David (ii Sam. 15:12; i Chron. 27:33-34): "Now, in those days, advice from Ahitho-phel was like an oracle from God" (ii Sam. 16:23). Ahithophel was the only one of David’s inner council who joined *Absalom in his revolt against his father (15:12). His defection was a source of great anxiety to David (15:31), and prompted him to charge *Hushai the Archite with counteracting Ahithophel’s counsel (15:34; 16:15ft.). On Ahithophel’s advice Absalom took possession of David’s concubines, thus demonstrating that the breach between him and his father was final (16:21). Ahithophel further proposed that he himself should pick 12,000 men and pursue David so as to overwhelm him at the nadir of his strength (17:1-3). Hushai, however, persuaded Absalom to muster a vast army before attempting to battle with such formidable adversaries as David and his professional warriors.

The Bible gives no details about Ahitub, and it is not clear whether he survived the destruction of Shiloh and continued to officiate as priest or died together with his family in the war against the Philistines (cf. Ps. 78:64). Some scholars assume that Ahitub settled in Nob, made it a priestly town, and officiated there over 85 priests (i Sam. 22:18) until his son *Ahimelech succeeded him. In ii Samuel 8:17 and i Chronicles 18:16 he is named as father of *Zadok, but this may be an attempt to link the priestly Zadokite line with the legitimate Aaronide line of Shiloh (cf. i Chron. 5:33-34; 6:37-38). It is doubtful, however, whether the Ahitub mentioned in the line of priests (ibid. 5:37-38; 9:11) refers to the same man. In the last cited verse he is called "the ruler [nagid] of the House of God."

The name Ahtb is found in an ancient Egyptian inscription (12-18 dynasties); Ahutab and Ahutabu appear in Akkadian; and Ahutab on an Elephantine ostracon.

AHITUB BEN ISAAC

(late 13th century), rabbi and physician in Palermo. Ahitub’s father was a rabbi and physician; his brother David was a physician. He became known while still a young man for his philosophic and scientific learning.

When the kabbalist Abraham *Abulafia went to Sicily to win adherents for his teaching, Solomon b. Abraham *Adret of Barcelona communicated with Ahitub in order to enlist his support in his controversy against Abulafia.

Ahitub was the author of Mah beret ha-Tene, a poem resembling the Mahberet ha-Tofet ve ha-Eden of *Immanuel of Rome. In this allegorical work he describes his journey to Paradise where he went to discover the right way of life. There he enjoyed the food of the blessed, and when he returned to earth he brought with him some of the waters of Paradise. These he used to water his garden which then yielded delicious fruits. The first of these he placed in a basket (tene), consecrated them to God, and then offered the fruits to anyone who wished to taste them. The number of these fruits was 13, representing the 13 *Articles of Faith. Ahitub’s work was incorporated in the Sefer ha-Tadir of Moses b. Jekuthiel de Rossi who added a piyyut on the articles of faith. This piyyut was published twice (A. Freimann, in zhb, 10 (1906), 172; Hirschfeld, in jqr, 5 (1914/15), 540).

Ahitub also translated Maimonides’ Treatise on Logic from the Arabic into Hebrew. This translation was still known in the 16th century, and its variant readings were recorded in the margins of some copies of the first edition of another Hebrew translation of the work, this one by Moses ibn *Tibbon. Ahitub’s translation was forgotten until a manuscript of it was found and published by Chamizer. An edition of the translation appears in Maimonides’ Treatise on Logic (ed. by I. Efros (1938), 67-100; cf. Eng. section, 8-9ff.).

AHLAB

(Heb. ![]() Canaanite city allotted to the tribe of Asher, which, however, was unable to conquer it at the beginning of the Israelite settlement (Judg. 1:31). This is apparently the same city of Asher which appears in the form me-Hevel (VariH; "from Hebel"; Josh. 19:29). According to the Septua-gint, this form is an error for Meheleb and it is mentioned as Mah alliba in Sennacherib’s account of his campaign in 701 b.c.e. between Zarephath (Zaribtu) and Ushu (mainland Tyre). Ahlab is identified with Khirbet el-Mah alib, on the Lebanese coast, 3/ mi. (6 km.) north of Tyre and approximately 1 mi. (2 km.) south of the mouth of the Litani River.

Canaanite city allotted to the tribe of Asher, which, however, was unable to conquer it at the beginning of the Israelite settlement (Judg. 1:31). This is apparently the same city of Asher which appears in the form me-Hevel (VariH; "from Hebel"; Josh. 19:29). According to the Septua-gint, this form is an error for Meheleb and it is mentioned as Mah alliba in Sennacherib’s account of his campaign in 701 b.c.e. between Zarephath (Zaribtu) and Ushu (mainland Tyre). Ahlab is identified with Khirbet el-Mah alib, on the Lebanese coast, 3/ mi. (6 km.) north of Tyre and approximately 1 mi. (2 km.) south of the mouth of the Litani River.

AHL AL-KITAB

(Ar. "The People of the Book"), name of the Jews, Christians, and Sabeans (al Sabda) in the Koran (Sura 3:110; 4:152; et al.) because they possess a kitab, i.e., a holy book containing a revelation of God’s word. Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry refers to Jewish and Christian Scripture. It especially dwells on the Zabur, a holy book – whose origin is from the word mizmor ("psalm") – which Muhammad knew as given to David (Sura 17:15), i.e., the Book of Psalms. Muhammad frequently mentions the tawra (the Torah, possibly the entire Bible) revealed to the Israelites (e.g., Sura 3:58, 87; 48:29) which contains clear allusions to Muhammad’s appearance (Sura 7:156; 33:44; 48:4). He also is acquainted with the Injil (Evangelium, the Gospels), a term which covers the entire New Testament. Muhammad emphasizes that the Injil confirms the statements of the Torah (Sura 5:50; cf. 48:29; 57:27). He does not specify the holy book of the Sabeans although he mentions them three times in the Koran (Sura 2:59; 5:72; 22:17), along with the Jews and the Christians, and promises them their part in salvation. According to the Arabs, Muhammad meant the Mandeans, a Judeo-Christian sect whose believers lived in Babylonia. In the early period of his mission, Muhammad related positively to the Ahl al-Kitab and their teachings. But his attitude changed as a result of the disappointment in his hope of persuading them to accept his faith. Then Muhammad accused them of intentionally falsifying the Torah or at least distorting its interpretation (Sura 2:70; 3:64, 72, 73; cf. 5:16; 6:91). Despite this, Muhammad determined that the Ahl al-Kitab, as the authors of holy books, deserve special treatment, and because they had agreed to pay the jizya ("poll tax"), the command to fight against them was not enforced (Sura 9:29). Since the Ahl al-Kitab fulfilled this condition, they became the Ahl al-Dhimma ("protected people"; see *Dhimmi). In a later period this position caused the Harran ("star worshipers") who called themselves Sabeans and the Persians, who believed in Zoroastrianism and relied on their holy book, to merit inclusion in the term Ahl al-Kitab.

As a result of their belief in the books of divine revelation, the Ahl al-Kitab enjoyed a favored status in Islam. A Muslim is permitted to intermarry with their women and to eat what they have slaughtered. On the other hand, the accusations of Muhammad as to falsifications of Scripture and distorted interpretations caused the creation of an extensive polemical literature and disputations which at times actually poisoned the relations between the adherents of the different religions.

AHLEM

Village near Hanover, known for its Jewish horticultural school, the first of its type in Germany. The school was founded in 1893 by the Jewish philanthropist Moritz Alexander Simon and was open to all suitable Jewish applicants, regardless of ideological affiliation. It trained hundreds of Jewish youths as agriculturalists and skilled workers. The three-year curriculum included agricultural subjects, especially horticulture, in addition to general subjects taught in secondary schools. On its foundation boys from the age of 14 were admitted; from 1903 to the 1920s girls over 16 were accepted for vocational training and home economics, and subsequently horticulture. A boarding school and elementary school for children between the ages of eight and 13 were added. In 1933 the number of pupils totaled approximately 50, but increased to 120 between 1936 and 1938. The school was authorized by the Nazis as a center for vocational training for Jewish youth intending to emigrate and was permitted to issue graduation certificates. Between 1933 and 1939 about 300 pupils graduated from Ahlem, and some of them emigrated to Erez Israel. Even before the closure of the school in July 1942, Ahlem was made an assembly point for the deportation of Jews by the Gestapo. Between December 1941 and February 1945, more than 2,400 Jews of the Hanover and Halberstadt region were deported from Ahlem to Riga, Theresienstadt, Warsaw, and Auschwitz. For a short time, the tradition of the Gartenbauschule was revived and a kibbutz was established by Holocaust survivors in Ahlem in 1945.

°AHLWARDT, HERMANN

(1846-1914), German publicist and antisemitic politician. In 1893, when headmaster of a primary school in Berlin, Ahlwardt was dismissed for embezzling money collected from the pupils. He made antisemitism his profession and used it as a political springboard. His first work, Der Verzweiflungskampf der arischen Voelker mit dem Judentum ("The Last Stand of the Aryan Peoples against Judaism," 1890-92), described an alleged Jewish world conspiracy. Its second part, "The Oath of a Jew" (Der Eid eines Judens), included slander against G. von *Bleichroeder, a leading Jewish banker. Prosecution followed and Ahlwardt was sentenced to four months’ imprisonment. He was hardly out of prison when he published another defamatory leaflet Judenflinten ("Jewish Rifles"), claiming that the guns supplied to the German Army by a Jewish manufacturer were defective. However, Ahlwardt was saved from serving a second sentence by parliamentary immunity, as he had been elected in 1892 to the Reichstag as member for Arnswalde-Friedeberg (Brandenburg) on the platform propounded to the peasants there that their misery was due to "the Jews and the Junkers." His pamphlets (no less than ten of which appeared in 1892) were assisted by the press and Roman Catholic clergy, with the result that antisemitic rioting, the burning of the synagogue at Neustettin, and the revival of ritual murder accusations ensued. To the embarrassment of his own party, the Conservatives, Ahlwardt occupied the time of the Reichstag with his slanderous "revelations" about the Jews. He continued to hold his seat there until the Reichstag was dissolved in 1893 when he was immediately imprisoned for libel. In spite of this and the opposition of the Conservatives he was reelected by the same constituencies and held his seat until 1902. He was sentenced for blackmail in 1909 and died unnoticed.

AHMADNAGAR

Capital of the former kingdom of the Nizam Shah dynasty on the west coast of India. Under Burhan Nizam Shah I (1510-53), a Shi’a Muslim, it became a center of Hindu-Muslim culture and learning. Among the scholars attracted to his court and enjoying its atmosphere of complete religious tolerance were some Marranos from Portugal, including Sancho Pirez, who became a favorite of the king and was a friend of Garcia *d’Orta. Garcia refers in his Colloquia (no. 26) to "Jews in the territory of Nizamuluco [Nizam Shah]." A Jewish settlement also existed in the port of the kingdom, Chaul (now Revanda).

AHOT KETANNAH

(Heb ![]() "Little Sister"), name of a hymn for Rosh Ha-Shanah. It was composed by Abraham Hazzan Gerondi, a writer of devotional hymns, who flourished about the middle of the 13th century in southern France. The poem consists of eight metrical stanzas of four to five lines, each ending with the refrain Tikhleh shanah ve-kileloteha ("May this year with its curses end"). The last stanza ends Tahel shanah u-virekhoteha ("May the year and its blessings begin"). The acrostic gives the name of the author "Abram Hazzan." The opening words of the hymn are taken from Song of Songs 8:8 "We have a little sister" and refer to the traditional allegorical interpretation of the Song of Songs. The poem evokes Israel’s sufferings in exile and implores God’s mercy "to fortify the song of the daughter and to strengthen her longing to be close to her lover." At first adopted into the Sephardi ritual, where it is recited before the evening prayer of Rosh Ha-Shanah, the poem was subsequently adopted in the Ashkenazi and Yemenite rites, especially in kabbalistic circles.

"Little Sister"), name of a hymn for Rosh Ha-Shanah. It was composed by Abraham Hazzan Gerondi, a writer of devotional hymns, who flourished about the middle of the 13th century in southern France. The poem consists of eight metrical stanzas of four to five lines, each ending with the refrain Tikhleh shanah ve-kileloteha ("May this year with its curses end"). The last stanza ends Tahel shanah u-virekhoteha ("May the year and its blessings begin"). The acrostic gives the name of the author "Abram Hazzan." The opening words of the hymn are taken from Song of Songs 8:8 "We have a little sister" and refer to the traditional allegorical interpretation of the Song of Songs. The poem evokes Israel’s sufferings in exile and implores God’s mercy "to fortify the song of the daughter and to strengthen her longing to be close to her lover." At first adopted into the Sephardi ritual, where it is recited before the evening prayer of Rosh Ha-Shanah, the poem was subsequently adopted in the Ashkenazi and Yemenite rites, especially in kabbalistic circles.

Music

Ahot Ketannah is sung either by the entire congregation, or by the cantor alone with the congregation joining in the refrain. The melody is uniform throughout the Sephardi Diaspora, with only slight local variations, and may therefore belong to the common pre-expulsion stock. Notated examples may be found in Idelsohn, Melodien, 1, no. 93; 2, no. 48 (mus. ex. 1); 3, nos. 43, 46, 175; 4, nos. 185, 186 (mus. ex. 2), 187, 192; 5, no. 159; Levy, Antologia, 2, nos. 93-101; F. Consolo.

AHRWEILER

(Heb. ![]() small German town near Bonn.

small German town near Bonn.

There was a considerable Jewish community in Ahrweiler in the 13th century, some of its members owning houses in Cologne. In the 14th century the Jews of Ahrweiler dealt in salt and wine. The community suffered during the *Black Death massacres of 1348. The physician and exegete Baruch b. Samson ("Meister Bendel") lived in Ahrweiler in the 15th century. Among the rabbis of Ahrweiler were Hayyim b. Johanan Treves (d. 1598), who also officiated as *Landrabbiner for the territory of the Electorate of Cologne, and his son-in-law Isaac b. Hayyim. A notable family which adopted the name "Ahrweiler" included among its members the Frankfurt dayyan Hirz Ahrweiler (d. 1679) and his son Mattathias, rabbi of Heidelberg (d. 1729). The small Ahrweiler community of modern times numbered only 4 Jews in 1808; 28 in 1849; 65 in 1900 (1% of the total population); and 31 in 1933. It maintained a cemetery and synagogue built in 1894. The synagogue was burned and desecrated on *Kristallnacht (Nov. 9-10, 1938); the last Jews were deported from Ahrweiler in July 1942.

AHWAZ

Capital of the Persian province of Khuzistan. Ahwaz was called Be-H ozai in the Talmud (Ta’an. 23; Pes. 50; Gitt. 89; Hull 95). Several amoraim originated from the city, including R. Aha, R. H anina, and R. Avram H oza’ah. As a junction between Babylonia and Persia, Ahwaz was an important medieval center for the eastern trade, with a flourishing Jewish population. Two Jews in the service of Caliph al-Muqtadir, Joseph b. Phinehas and Aaron b. Amram, were tax farmers for the province, owning real estate and a bazaar there which yielded a considerable income. They rose to the position of court bankers. The revenue from Ahwaz province is mentioned as security for a large loan they advanced to the government. Ahwaz remained a center of Jewish commercial activities throughout the Middle Ages, as attested by correspondence between Jewish merchants in Ahwaz with associates in *Fez and *Cairo. One of the earliest indications that Jewish merchants in Khuzistan used the Persian language is a Judeo-Persian law report, dated around 1021, found near Ahwaz.

As in *Abadan, Ahwaz became one of the first centers of Zionist activitiy in Iran beginning with the occupation of the southern region by the British Army (Sept. 1941). During this period there were 300 Jews in Ahwaz, constituting 70 families, many of them immigrants from Iraq and from other cities like *Isfahan, *Shiraz, *Kashan, Arak, and *Kermanshah. The majority were merchants, mainly in the textile trade. There were five wealthy families in Ahwaz; the rest belonged to the middle class. There were two synagogues, one belonging to Jews of Iraqi origin and the other to Persian-speaking Jews. After 1948, many Jews immigrated to Israel and to *Teheran. The majority of the Jews of Ahwaz left the city after the Islamic Revolution (1979). At the beginning of the 21st century, there were fewer than five families living there.

AI or HA AI

![]() in the Samaritan version of Gen. 12:15 called Ayna; in Jos., Ant. 5:35 – Naian), place in Erez Israel. It is mentioned together with Beth-El as near the site where Abraham pitched his tent (Gen. 12:8; 13:3). In Joshua 7:2, it is located beside Beth-Aven, east of Beth-El. Ai was the second Canaanite city which Joshua attacked (Josh. 7-8). After the first attempt to capture the city had miscarried because of the sin of *Achan, the king of Ai and his army were defeated in an ambush and the city was left in ruins (see also Josh. 12:9). Although the old site of Ai remained abandoned, an Israelite city with a similar name arose nearby. Isaiah mentioned Aiath (n?y – Isa. 10:28) as the first of the cities occupied by the Assyrians in their march on Jerusalem, before Michmas and Geba. In the post-Exilic period, returnees from Ai are mentioned together with people from Beth-El (Ezra 2:28; Neh. 7:32) and Aijah (n?J7) appears as a city of Benjamin (Neh. 11:31). Most scholars identify the ancient city with et-Tell near Deir Dib-wan, c. 1 mi. (2 km.) southwest of Beth-El. Excavations at the site carried out in 1933-35 by Judith Marquet-Krause were renewed in 1964 by J.A. Callaway. The city was found to have been inhabited in the Early Bronze Age from c. 3000 B.c.E. Several massive stone walls were discovered as well as a sanctuary containing sacrificial objects and a palace with a large hall, the roof of which was supported by wooden pillars on stone bases. The city was destroyed not later than in the 24th century B.c.E. and remained in ruins until the 13th or 12th century B.c.E. when a small short-lived Israelite village was established there. This discovery indicates that in the time of Joshua, the site was a waste (also implied by the name Ai, literally, "ruin"). Scholars explain the discrepancy in various ways. Some consider the narrative of the conquest of Ai contained in the book of Joshua an etiological story that developed in order to explain the ancient ruins of the city and its fortifications. Others assume that the story of Ai was confused with that of nearby Beth-El which evidently was captured during the 13th century. Others dispute the identification without, however, being able to propose another suitable site. Khirbet H aiyan, c. 1 mi. (2 km.) south of et-Tell, has been suggested as the site of the later city; the only pottery found there, however, dates from the Roman and later periods.

in the Samaritan version of Gen. 12:15 called Ayna; in Jos., Ant. 5:35 – Naian), place in Erez Israel. It is mentioned together with Beth-El as near the site where Abraham pitched his tent (Gen. 12:8; 13:3). In Joshua 7:2, it is located beside Beth-Aven, east of Beth-El. Ai was the second Canaanite city which Joshua attacked (Josh. 7-8). After the first attempt to capture the city had miscarried because of the sin of *Achan, the king of Ai and his army were defeated in an ambush and the city was left in ruins (see also Josh. 12:9). Although the old site of Ai remained abandoned, an Israelite city with a similar name arose nearby. Isaiah mentioned Aiath (n?y – Isa. 10:28) as the first of the cities occupied by the Assyrians in their march on Jerusalem, before Michmas and Geba. In the post-Exilic period, returnees from Ai are mentioned together with people from Beth-El (Ezra 2:28; Neh. 7:32) and Aijah (n?J7) appears as a city of Benjamin (Neh. 11:31). Most scholars identify the ancient city with et-Tell near Deir Dib-wan, c. 1 mi. (2 km.) southwest of Beth-El. Excavations at the site carried out in 1933-35 by Judith Marquet-Krause were renewed in 1964 by J.A. Callaway. The city was found to have been inhabited in the Early Bronze Age from c. 3000 B.c.E. Several massive stone walls were discovered as well as a sanctuary containing sacrificial objects and a palace with a large hall, the roof of which was supported by wooden pillars on stone bases. The city was destroyed not later than in the 24th century B.c.E. and remained in ruins until the 13th or 12th century B.c.E. when a small short-lived Israelite village was established there. This discovery indicates that in the time of Joshua, the site was a waste (also implied by the name Ai, literally, "ruin"). Scholars explain the discrepancy in various ways. Some consider the narrative of the conquest of Ai contained in the book of Joshua an etiological story that developed in order to explain the ancient ruins of the city and its fortifications. Others assume that the story of Ai was confused with that of nearby Beth-El which evidently was captured during the 13th century. Others dispute the identification without, however, being able to propose another suitable site. Khirbet H aiyan, c. 1 mi. (2 km.) south of et-Tell, has been suggested as the site of the later city; the only pottery found there, however, dates from the Roman and later periods.

AIBU

(1) Babylonian sage who flourished in the transitional period from the tannaim to the amoraim (late second – early third century c.e.). The father of *Rav and the brother of H iyya (Pes. 4a; Sanh. 5a), he studied in Erez Israel, where he frequently visited Eleazar b. Zadok, whose customs and halakhic decisions he quotes (Suk. 44b).

(2) The son of Rav, who told him "I have labored with you in halakhah, but without success. Come and I will teach you worldly wisdom" (Pes. 113a).

(3) The grandson of Rav (Suk. 44b), and a frequent visitor to his home.

(4) Amora and prominent aggadist (late third – early fourth century c.e.). While he transmitted some halakhic statements in the name of Yannai (Ket. 54b; Kid. 19a; et al.), he was mainly interested in aggadah, quoting the aggadic interpretations of tannaim and amoraim such as R. Meir (Mid. Ps. 101, end), R. Eliezer b. R. Yose ha-Gelili (Tanh. B., No’ah, 24, 53), and R. Johanan (Gen. R. 82, 5). His aggadic comments, popular among homilists, were frequently quoted by them, especially by R. Yudan b. Simeon (ibid., 73:3; Mid. Ps. 24:11; et al.), R. Huna, R. Phinehas, and R. Berechiah. One of his aggadic maxims is "No man departs from this world with half his desires realized. If he has a hundred, he wants two hundred, and if he has two hundred, he wants four hundred" (Eccl. R. 1:13).

The novel explores the angst and suffering of both the Jews and their pursuers during the Third Reich. The text reflects Aichinger’s commitment to the weak and skepticism about the German language. After 1950, she was employed as a reader at the S. Fischer publishing house. In 1953 she married Guenter Eich, whom she had met at a conference of the "Gruppe 47," where she received an award for her Spiegelgeschichte. This is a piece of literary prose that narrates a reversed life with the attempt to unlearn everything including language and thus postulating silence. Aichinger’s collection of narratives Rede unter dem Galgen was also published in 1953. In these narratives she examines a range of human emotions, including angst, alienation, paradox, and ambivalence. Aichingers lyric and narrative texts increasingly show the reduction of linguistic means focusing on subjectivity, thereby blending reality and dream, inner and outer world. Examples of these themes can be found in Eliza Eliza (1965), Schlechte Woerter (1976), Verschenkter Rat (1978) or Kleist, Moos, Fasane (1984). Aichinger also published a number of radio plays, including Knoepfe (1953), Besuch im Pfarrhaus (1962), Auckland (1970), and the radio dialog Belvedere (1995). These radio plays illustrate existential borderline experiences between assimilation and resistance. A later publication is Film und Verhaengnis: Blitzlichter auf ein Leben (2001), notes on films and photography which turn a spotlight on the cultural life of Vienna between 1921 and 1945.

Aichinger’s awards over the years include the Nelly Sachs-Preis, the Georg Trakl-Preis, the Franz Kafka-Preis, and the Joseph-Breitbach-Preis. She was a member of the Deutsche Akademie fuerr Sprache und Dichtung, the Akad-emie der Kuenste Berlin, and the Bayerische Akademie der Schoenen Kunste.

AICHINGER, ILSE

(1921- ), Austrian writer and lyricist, and author of radio plays. One of twin daughters born to a Jewish physician and a teacher, Aichinger spent her childhood in Linz and after the early divorce of her parents moved to Vienna. There she and her maternal relatives were confronted with the persecution of the Nazi regime. In her first publication, Aufruf zum Mifitrauen (1946), she cautioned against what she perceived to be a new and dangerous self-confidence in Austria after the collapse of Nazi rule. At an early age, she had expressed an interest in studying medicine, but she was unable to do so because of the Nuremberg Laws. At the end of World War ii, she was able to pursue her interest in medicine, but dropped out of university in 1948 to complete her first uated in a broad valley (valley of Aijalon) which is one of the approaches to the Judean Hills. Volcanic activity occurring in the area in the latest geological period left some basalt traces and the hot springs found at *Emmaus in ancient times. Potsherds found on a large tell, about 3 mi. (5 km.) north of Bab-al-Wad, show continuous occupation from the Late Bronze Age onward. The village of Yalu is built on the tell.

The El-Amarna letters indicate that the region was included within the kingdom of Gezer in the 15th and 14th centuries, b.c.e. This kingdom was on hostile terms with Jerusalem, whose ruler Puti-Hepa complained that his caravans were being robbed in the valley of Aijalon ("Yaluna," ea, 287). In a letter to Amenhotep iv (ea, 273), the queen of the city of Zaphon (?) reports that the Habiru attacked the two sons of Milkilu, king of Gezer, in Ayaluna (Aijalon) and in Sarha (Zorah). Joshua referred to the valley of Aijalon in connection with his defeat of the Amorites. Joshua asked for a miracle to prevent the sun from setting so that the Israelites could avenge themselves on the Amorites. Joshua said: "Sun, stand thou still upon Gibeon; and thou, Moon, in the valley of Aijalon" (Josh. 10:12). The city is included in the tribal area of Dan (Josh. 19:42) and in the list of levitical cities (Josh. 21:24; 1 Chron. 6:54), but the Danites were unable to subject the Amorites, and later the region came under the influence of the "house of Joseph" (Ephraim; Judg. 1:34-35). The valley became a field of battle between the tribes of Dan, Ephraim, Judah, and Benjamin on the one side and the Amorites and Philistines on the other (1 Chron. 7:21; 8:6). The region was finally conquered by the Israelites under David. Aijalon is included in Solomon’s second administrative district under "the son of Deker" (1 Kings 4:9). With the division of the kingdom, the valley remained within the kingdom of Judah, in the territory of Benjamin, and Rehoboam fortified it as part of his defense system of Jerusalem (11 Chron. 11:10). It is mentioned in the list of cities (no. 26) captured by Shishak, king of Egypt, in about 924 B.c.E. and the Philistines also captured it during the reign of Ahaz but held it only briefly (11 Chron. 28:18). There is no reference to Aijalon during the Second Temple period. The valley was located on the route taken by Cestius Gallus, the governor of Syria, in his campaign against Jerusalem in 66 c.E. (Jos., Wars, 2:513-6). In Byzantine times, Aijalon is mentioned as Ialo, a name which is preserved in the present-day Arab village of Yalu.

In 637 c.E., Aijalon was the headquarters of the Arab armies which suffered heavily at Emmaus. The region was badly damaged in an 11th-century earthquake. During the Crusades it was once again a battlefield and a fort was built there by the Crusaders (today *Latrun). It was also a scene of fighting during Allenby’s campaign in 1917 and in the War of Independence (1948) a prolonged battle was fought in the region over the roads leading to Jerusalem. After the War of Independence, a few Israeli settlements were established in the region. These were considered border settlements, and during the 1950s they were under terrorist attack. In 1967 the whole area was occupied by the Israel Defense Forces, and the Arab inhabitants fled to Ramallah. In 1976 a large park was established on the deserted land of the Arab villages.

(2) Town in the territory of Zebulun where the judge, Elon, was buried (Judg. 12:12). Its location is unknown.

AIKEN, HENRY DAVID

(1912-1982), U.S. philosopher. Aiken was born in Portland, Oregon, and taught at the universities of Columbia, Washington, Harvard (1946-65), and Brandeis (1965-80), specializing in ethics, esthetics, and the history of philosophy. He was influenced by the British analytic movement, by the American naturalists – especially San-tayana, and by David Hume’s moral and political writings, some of which he edited. Among the works he wrote are The Age of Ideology (1957), selections including a commentary on 19th-century thought; Reason and Conduct (1962), a collection of essays in moral philosophy; and Predicament of the University (1971).

AIKHENVALD YULI ISAYEVICH

(1872-1928), Russian literary critic and essayist. An opponent of the dominant school of social criticism, he made his name as a major exponent of the subjective, impressionist approach. His works include Pushkin (1908), Etyudy O zapadnykh pisatelyakh ("Studies of Western Writers," 1910), Siluety russkikh pisateley ("Outlines of Russian Writers," 3 vols. (1906-1910)), and Spor o Belinskom ("The Belinski Controversy," 1914), an appraisal of Vissarion Belinski, the first Russian to view literary criticism as a molder of public opinion. In 1922 Aikhenvald and a number of other non-communist intellectuals were expelled from the U.S.S.R. He was killed in a streetcar accident in Berlin.

AIMEE, ANOUK

(Fran^oise Dreyfus; 1932- ), French actress. Starting her film career as a teenager and the daughter of actress Genevieve Sorya, the Paris-born Aimee gained the attention of the French public in 1957 in the film Les Mauvaises Rencontres. In Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), and 8′A (1963), she was cast in roles reflecting modern boredom and world-weariness. She was nominated for an Academy Award as best actress for her part in Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman (1966). Among her more than 80 films are Justine (1969), The Appointment (1970), Salto nel Vuoto (Cannes Award for Best Actress, 1980), Un Homme et une Femme: 20 Ans deja (1986), Ily a desjours…et des lunes (1990), and Robert Altman’s Ready to Wear (1994). She was married to the actor Albert Finney from 1970 to 1978.

°AINSWORTH, HENRY

(1569-1622), English Bible scholar. Ainsworth was educated at Cambridge and already knew Hebrew when, as an adherent of the Brownist sect (later called Congregationalists), he went into exile in Amsterdam. He served there as a teacher (1596-1610) in the independent English Church, and subsequently as its minister. Through Jewish contacts in Amsterdam he improved his Hebrew knowledge, the considerable extent of which is reflected in his writings. These include Silk or Wool in the High Priests Ephod… (London, 1605); an English version, with annotations, of Psalms (Amsterdam, 1612), which was adopted by the Puritans of New England until they produced their own in 1640; and Annotations to the Pentateuch, with Psalms and Song of Songs (1616-27). This work, which includes rabbinic material, was translated into Dutch in 1690 and into German in 1692; Song of Songs in English meter in 1623. Ainsworth’s Annotations were used two and a half centuries later by the revisers of the English Bible. He was considered one of the finest English Hebraists of his time.

AISH HATORAH

Outreach organization based in Jerusalem, Israel, and housed in a building facing the Western Wall, directly above the plaza. It was founded by American-born rabbi Noah Weinberger in 1974. Weinberger had grown up on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where he was raised in an Orthodox home and was proud of his mother’s involvement in the establishment of the Esther Schoenfeld Beth Jacob School for Girls. He saw his mission as fighting assimilation and answering the question, "Why be Jewish?" His strategy involved the use of high technology and powerful and media-savvy business executives and celebrities to help send out his institution’s message. It operates 26 full-time branches and offers programs in 80 cities, representing 17 countries on five continents and attended by 100,000 people annually in addition to the 4,500 students who study at Aish Jerusalem every year. Over 175 people have graduated from the rabbinic program and have gone to North America to do outreach work.

Aish Programs

discovery. A one-day program that explores the rational basis for Jewish belief and practice. More than 100,000 people worldwide have attended the Discovery program. Guest hosts for these seminars have included American entertainers Ed *Asner, Kirk *Douglas, Elliot *Gould, Joel *Grey, and Jason ^Alexander. Aish instructors conduct hundreds of related seminars in cities around the world, including Johannesburg, London, Sydney, Melbourne, Santiago, and Jerusalem, as well as in 45 U.S. cities for university campuses, Jewish community centers, and Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox synagogues.

The executive learning program. Successful men and women of all ages participate in individually designed personal study programs in their homes and offices. With limited free time, and often with limited background in Judaism, hundreds of busy executives find a way to fit Torah study into their active lives. Among those who participate are Robert Hormats, vice chairman of Goldman-Sachs International, and Michael Goldstein, ceo of Toys R Us.

The israel experience. The 4,500 people participating in Aish Jerusalem programs in Israel attend the Discovery Seminar; the one-month Essentials for men or jewel for women; introductory programs; and the Jerusalem Fellowships. The latter was founded in 1985 by senators Daniel Patrick Moyni-han and Arlen Spector. The program combines touring Israel, studying Judaism, and meeting Israel’s top leadership from across the political spectrum.

Eyaht college of jewish studies for women. Reb-betzin Denah Weinberg founded the school in 1990 to empower Jewish women.

The Russian program. This reaches over 50,000 people in the Former Soviet Union (fsu), plus another 3.5 million viewers through its popular television series. In Moscow, Aish runs the Intellectual Cafe, a bimonthly seminar teaching Talmud to beginners through a logic game. Aish-Fsu has four permanent branches, including one accredited college.

In Israel, Aish created a social action organization, aviv, which provides legal, medical, and social services to aid Russian Jews after they make aliyah. Aish has also created a series for Radio Reka, the immigrant radio station that has 200,000 listeners in Israel and one million in Russia.

High tech and Jerusalem fund missions to israel. The Albert Einstein High Tech Mission brings leaders of hitech industry to Israel to meet their peers and explore potential investments, strategic partnerships, and spirituality in the Holy Land. Companies who have participated include the founders, ceos, or presidents of aol, Infospace, Ness, National Semiconductor, Computer Associates, idt, Drug-store.com, ZDNet, StarTek, Net2Phone, The Red Herring, Draper Fisher Jurvetson, Scient, Disney Internet, Akamai, and ATT.com.

The theodor herzl mission. Co-sponsored with the mayor of Jerusalem, it brings world leaders from across the world to Israel for one week. Participants have included Lady Margaret Thatcher, U.S. senators John Kerry, Harry Reid, and Joseph Biden, former House speaker Newt Gingrich, former U.S. Ambassador to the un Jeanne Kirkpatrick, Congressman Peter Deutsch, Governors Tom Ridge (pa) and Christine Whitman (nj), philanthropist Carroll Petrie, Elie Wiesel, Alan Dershowitz, Barry Sternlicht, chairman of Starwood Hotels, the world’s largest hotel company, Starbuck’s Howard Schultz, and Accuweather president Joel Meyer.

The capital campaign. Aish HaTorah is building a hitech Jewish education center incorporating state of the art Internet, video, computer, and satellite hook-ups. The Kirk Douglas Theater, dedicated by the Hollywood legend, will present a film about the Jewish contribution to humanity. Aish also acquired several sites in the Old City, projected for use as classrooms, dormitories, and offices.

Aish.com. With its 1,000,000 hits a year, the site is user-friendly, hi-speed, and full of information and contact numbers about all of its programs.

![tmp129-56_thumb[1] tmp129-56_thumb[1]](http://what-when-how.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/tmp12956_thumb1_thumb.jpg)