AESCOLY (Weintraub), AARON ZE’EV

(1901-1948), Hebrew writer, historian, and ethnologist. Aescoly studied in Berlin, Liege, and Paris, where for a short time he taught at the Ecole Nationale des Langues Orientales Vivantes. In 1925 he immigrated to Palestine, although he did scholarly research in Paris from 1925 to 1930 and from 1937 to 1939. From 1939 he directed the I. Epstein Training College for kindergarten teachers which he had founded. During World War 11 he served in the British Army and, as chaplain, in the Jewish Brigade. Aescoly’s contributions to Jewish scholarship cover a wide field. In the introduction to his critical edition of Sippur David Reuveni ("Story of David Reuveni," 1940), and in a number of other studies, he dealt with messianic movements. His edition of Hayyim Vital’s Sefer ha-Hezyonot (1954) and his Ha-Tenuot ha-Meshihiyyot be-Yisrael ("Messianic Movements in Israel," 1956) were both published posthumously. His ethnological writings include Geza ha-Adam ("The Human Race," 19562), Yisrael (19532), and a number of studies on the *Beta Israel (Sefer ha-Falashim, 1943; Habash, 1936; Recueil de textes falashas, 1951). Aescoly’s historical studies include Ha-Emanzipazyah ha-Yehudit, Ha-Mahpekhah ha-Zarefatit u-MalkhutNapoleon ("Jewish Emancipation, the French Revolution and the Reign of Napoleon," 1952); a history of his native community of Lodz (1948); and an edition of S. Luzzatto’s book on the Jews of Venice (published with D. Lattes’ translation, 1951). On literature he wrote Maamar ha-Sifrut (1941) and translated writings of Lao-Tse (1937). He also edited S.D. Luzzatto’s Yesodei ha-Torah (1947). ibliography: Kressel, Leksikon, 1 (1956), 161.

AFENDOPOLO, CALEB BEN ELIJAH

(1464?-1525), Karaite scholar and poet. Born probably in Adrianople, he lived most of his life in the village of Kramariya near *Constanti-nople, and ultimately in *Belgrade where he died. A pupil of his brother-in-law, Elijah *Bashyazi, Afendopolo remained an Orthodox Karaite of the school of *Aaron b. Elijah of Nicome-dia, although he was on friendly terms with several Rabbanite scholars. He acquired much of his knowledge of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and Greek-Arabic philosophy, including the works of Maimonides, from the Rabbanite Mordecai *Comtino, and learned modern languages, such as Italian, Greek, and Arabic. Maimonides’ views on the messianic era and on the purpose of the commandments proved a formative influence. Afendopolo taught and wrote on a variety of subjects. Most of his numerous treatises remain in manuscript, now in various collections, and often treat diverse unrelated topics.

While surpassing his Karaite contemporaries in the depth and breadth of his scientific studies, Afendopolo lacked originality. A talented eclectic, he mastered the wealth of past and contemporary scholarly material at his disposal, and his writings are a valuable source of reference concerning scholars and works whose existence would otherwise remain unknown. He owned an extensive library of original manuscripts as well as copies he made himself. His works include (1) an unfinished supplement to Adderet Eliyahu by Elijah Bashyazi (1532); (2) Iggeret ha-Maspeket, on dietary and other laws; (3) Patshegen Ketav ha-Dat, on the reading of the Pentateuch and haftarot; (4) Asarah Maamarot, sermons reflecting his religious views (fragments are included in Dod Mordekhai by *Mordecai b. Nisan ha-Zaken, Hamburg, 1714); (5) indices to Ez Hayyim by Aaron b. Elijah and to Eshkol ha-Kofer by Judah b. Elijah *Hadassi; (6) Avner ben Ner, a discourse on ethics in the style of the Arabic maqamat; (7) Gan ha-Melekh, poetry and prose, containing autobiographical and historical details as well as two elegies on the expulsion of the Jews from Lithuania in 1495; (8) Mikhlal Yofi, on the principles of astronomy, withrelation to the calculation of the calendar (9) liturgical poems, included in the Karaite prayer book; (10) a commentary on the Nicomachean arithmetic; (11) Gal Einai, on astronomy (known only by the title); and (12) Iggeret Maspeket, mainly a glossary of astronomical terminology.

°AFFONSO

Name of several kings of Portugal. affonso henriques (1139-1185), the first king of Portugal, continued the relatively tolerant policy to the Jews of his Castilian forebears, giving the Jews autonomy in civil as well as criminal cases. His almoxarife or treasurer was Yahia ibn Ya’ish, to whom he granted considerable privileges. His grandson, affonso ii (1211-1223), also had Jews in his employment in responsible offices, though he confirmed the anti-Jewish provisions of the *Lateran Council of 1215 and endorsed the resolutions passed by the Cortes at Coimbra encouraging baptisms. affonso iii (1245/8-1279) on the other hand, almost systematically disregarding many ecclesiastical restrictions against the Jews, employed them widely in the financial administration, and reorganized the internal affairs of the Jews of the kingdom. He was responsible, among other matters, for the organization of the office of chief rabbi (*Arraby moor) of Portugal, with its far-reaching powers. affonso iv (1325-1357) was unfavorably disposed toward the Jews, enforced the wearing of the Jewish *badge, and restricted the right of emigration for any person of property. affonso v (1438-1481) relaxed the enforcement of the anti-Jewish regulations. He is memorable for having in his service Isaac *Abra-banel and Joseph ibn Yahia, with whom he is said to have had learned discussions on science and philosophy. He attempted with only qualified success to suppress the anti-Jewish riots of 1449 and punish the ringleaders. In his compilation of laws, collected under the title Ordenafoes Affonsinas, the regulations concerning the Jews occupy a prominent place (book 2). In an edict of 1468, while renewing the restriction of the Jews to their judiarias, he permitted them to do business at the fairs elsewhere.

AFGHANISTAN

Muslim state in central Asia (Khorasan or Khurasan in medieval Muslim and Hebrew sources).

History

Early Karaite and Rabbanite biblical commentators regarded Khorasan as a location of the lost *Ten Tribes. Afghanistan annals also trace the Hebrew origin of some of the Afghan tribes, in particular the Durrani, the Yussafzai, and the Afridi, to King *Saul (Talut). This belief appears in the 17th-century Afghan chronicle Makhzan-i-Afghan, and some British travelers in the 19th century spread the tradition. Because of its remoteness from the Jewish center in Babylonia, persons unwanted by the Jewish leadership, such as counter-candidates for the exilarchate (see *Exilarch), often went to live in or were exiled to Afghanistan.

Medieval sources mention several Jewish centers in Afghanistan, of which *Balkh was the most important. A Jewish community in Ghazni is recorded in Muslim sources, indicating that Jews were living there in the tenth and eleventh centuries. A Jew named Isaac, an agent of Sultan Mahmud (ruled 998-1030), was assigned to administer the sultan’s lead mines and to melt ore for him. According to Hebrew sources, vast numbers of Jews lived in Ghazni but while their figures are not reliable, Moses *Ibn Ezra (1080) mentions over 40,000 Jews paying tribute in Ghazni and *Benjamin of Tudela (c. 1170) describes "Ghazni the great city on the River Gozan, where there are about 80,000 [8,000 in a variant manuscript] Jews.." In Hebrew literature the River Gozan was identified with Ghazni in Khorasan from the assertion of Judah *Ibn Bal’am that "the River of Gozan is that river flowing through the city of Ghazni which is today the capital of Khorasan."

A Jewish community in Firoz Koh, capital of the medieval rulers of Ghur or Ghuristan, situated halfway between Herat and Kabul, is mentioned in Tabaqat-i-Nasirt, a chronicle written in Persian (completed around 1260) by al-Juzjani. This is the first literary reference to Jews in the capital of the Ghurids. About 20 recently discovered stone tablets, with Persian and Hebrew inscriptions dating from 1115 to 1215, confirm the existence of a Jewish community there. The Mongol invasion in 1222 annihilated Firoz Koh and its Jewish community.

Arab geographers of the tenth century (Ibn Hawqal, Istakhri) also refer to Kabul and Kandahar as Jewish settlements. An inscription on a tombstone from the vicinity of Kabul dated 1365, erected in memory of a Moses b. Ephraim Bezalel, apparently a high official, indicates the continuous existence of a Jewish settlement there.

Map of Afghanistan showing places of Jewish settlement in the Middle Ages and modern times.

The Mongol invasion, epidemics, and continuous warfare made inroads into Jewish communities in Afghanistan throughout the centuries, and little is known about them until the 19th century when they are mentioned in connection with the flight of the *anusim of Meshed after the forced conversions in 1839. Many of the refugees fled to Afghanistan, Turkestan, and Bokhara, settling in Herat, Maimana, Kabul, and other places with Jewish communities, where they helped to enrich the stagnating cultural life. Nineteenth-century travelers (*Wolff, *Vambery, *Neumark, and others) state that the Jewish communities of Afghanistan were largely composed of these Meshed Jews. Mattathias Garji of Herat confirmed: "Our forefathers used to live in Meshed under Persian rule but in consequence of the persecutions to which they were subjected came to Herat to live under Afghan rule." The language spoken by Afghan Jews is not the Pushtu of their surroundings but a *Judeo-Persian dialect in which they have produced fine liturgical and religious poetry. Their literary merit was recognized when Afghan Jews moved to Erez Israel toward the end of the 19th century. Scholars of Afghanistan families such as Garji and Shaul of Herat published Judeo-Persian commentaries on the Bible, Psalms, piyyutim, and other works, at the Judeo-Persian printing press established in Jerusalem at the beginning of the 20th century. The Jews of Afghanistan did not benefit from the activities of European Jewish organizations. Economically, their situation in the last century was not unfavorable; they traded in skins, carpets, and antiquities.

Recent Years

Approximately 5,000 Jews were living in Afghanistan in 1948. Of these, about 300 remained in 1969. They were concentrated in Kabul, Balkh, and mainly Herat. (See Map: Jews in Afghanistan.) Jews were banished from other towns after the assassination of King Nadir Shah in 1933. Though not forced to live in separate quarters, Jews did so and in Balkh they even closed the ghetto gates at night. A campaign against Jews began in 1933. They were forbidden to leave a town without a permit. They had to pay a yearly poll tax and from 1952, when the Military Service Law ceased to apply to Jews, they had to pay ransoms for exemptions from the service (called harbiyya). Government service and government schools were closed to Jews, and certain livelihoods forbidden to them. Consequently, most Jews only received a heder education. There were only a few wealthy families, the rest being poverty-stricken and mostly employed as tailors and shoemakers. Until 1950 Afghan Jews were forbidden to leave the country. However, between June 1948 and June 1950, 459 Afghan Jews went to Israel. Most of them had fled the country in 1944, and lived in Iran or India until the establishment of the State of Israel. Jews were only allowed to emigrate from Afghanistan from the end of 1951. By 1967, 4,000 had gone to Israel. No Zionist activity was permitted, and no emissaries from Israel could reach Afghanistan. There was a hevrah ("community council") in each of the three towns in which Jews lived. The hevrah was composed of the heads of families; it cared for the needy, and dealt with burials. The hevrah sometimes meted out punishments, including excommunication. The head of the community (called kalantar) represented the community in dealings with the authorities, and was responsible for the payment of taxes.

According to the New York Times, one Jew remained in Afghanistan in 2005.

Folklore

A survey of local Jewish-Afghan folk tales and customs reveals the influence of both Meshed (Jewish-Persian) and local non-Jewish traditions. This is especially true of customs relating to the year cycle and life cycle. The existence of several unique customs, such as the presence of "Elijah’s rod" at childbirth, and several folk cures and charms are to be similarly explained. Jewish-Afghan folk tales have been collected from local narrators in Israel and are preserved in the Israel Folk Tale Archives. A sample selection of 12 tales from the repertoire of an outstanding narrator, Raphael Yehoshua, was published in 1969, accompanied by extensive notes and a rich bibliography.

AFIKE JEHUDA

(Heb ![]() society for the "advancement of study of Judaism and of religious consciousness" founded in Prague in 1869 on the initiative of Samuel Freund, and named in memory of Judah Teweles. It supported the talmud torah (until taken over by the community in 1879), and Teweles’ yeshivah. The society organized lectures (to which women were admitted from 1879) by outstanding scholars and published them, mainly in the two anniversary volumes, Afike Jehuda Festschrift (1909 and 1930). A project initiated in 1919 by the society to publish a Jewish biographical lexicon did not materialize. The society continued to exist until the German occupation of Prague in 1939.

society for the "advancement of study of Judaism and of religious consciousness" founded in Prague in 1869 on the initiative of Samuel Freund, and named in memory of Judah Teweles. It supported the talmud torah (until taken over by the community in 1879), and Teweles’ yeshivah. The society organized lectures (to which women were admitted from 1879) by outstanding scholars and published them, mainly in the two anniversary volumes, Afike Jehuda Festschrift (1909 and 1930). A project initiated in 1919 by the society to publish a Jewish biographical lexicon did not materialize. The society continued to exist until the German occupation of Prague in 1939.

AFIKIM

(Heb ![]() "stream courses" referring to the Jor was 1,030. In addition to engaging in intensive farming (irrigated field crops, fodder, milch cattle, poultry, carp ponds, bananas, dates, grapefruit), the kibbutz economy was based on a large plywood factory, producing principally for export. It also became a partner in the nearby factory for cellotex and similar materials. The prehistoric site of al-’Ubaydiyya is situated near the kibbutz.

"stream courses" referring to the Jor was 1,030. In addition to engaging in intensive farming (irrigated field crops, fodder, milch cattle, poultry, carp ponds, bananas, dates, grapefruit), the kibbutz economy was based on a large plywood factory, producing principally for export. It also became a partner in the nearby factory for cellotex and similar materials. The prehistoric site of al-’Ubaydiyya is situated near the kibbutz.

AFIKOMAN

(Heb. ![]() name of a portion of mazzah (unleavened bread) eaten at the conclusion of the Passover evening meal. In most traditions, early in the evening, the person conducting the seder breaks the middle of the three mazzot into two pieces, putting away the larger portion, designated as afikoman, for consumption at the conclusion of the meal. Some Yemenites, who use only two mazzot, break off a part of the lower mazzah just at the beginning of the meal. The word afikoman, of Greek origin but uncertain etymology, probably refers to the aftermeal songs and entertainment (cf. tj, Pes. 10:8, 37d), accompanied by drinking, which was common after festive meals in ancient times. The Mishnah states: "One may not add afikoman after the paschal meal" (Pes. 10:8), for the paschal meal was not to be followed by customary revelry (Pes. ii9b-i20a). This ruling was later understood to mean that the paschal lamb should be the last food eaten during the evening and, after the cessation of the paschal sacrifice, mazzah replaced it as the last food eaten during the evening. This mazzah is first referred to as afikoman in medieval times (cf. Mahzor Vitry). This afikoman has become a symbolic reminder of the paschal sacrifice.

name of a portion of mazzah (unleavened bread) eaten at the conclusion of the Passover evening meal. In most traditions, early in the evening, the person conducting the seder breaks the middle of the three mazzot into two pieces, putting away the larger portion, designated as afikoman, for consumption at the conclusion of the meal. Some Yemenites, who use only two mazzot, break off a part of the lower mazzah just at the beginning of the meal. The word afikoman, of Greek origin but uncertain etymology, probably refers to the aftermeal songs and entertainment (cf. tj, Pes. 10:8, 37d), accompanied by drinking, which was common after festive meals in ancient times. The Mishnah states: "One may not add afikoman after the paschal meal" (Pes. 10:8), for the paschal meal was not to be followed by customary revelry (Pes. ii9b-i20a). This ruling was later understood to mean that the paschal lamb should be the last food eaten during the evening and, after the cessation of the paschal sacrifice, mazzah replaced it as the last food eaten during the evening. This mazzah is first referred to as afikoman in medieval times (cf. Mahzor Vitry). This afikoman has become a symbolic reminder of the paschal sacrifice.

In many Ashkenazi communities it is customary for the children present to attempt to "steal" the afikoman from the person leading the seder (who therefore tries to "hide" it from them). A favorite time for such a "theft" is while the leader is washing his hands before the meal, and the "ransom" is usually the promise of presents. The custom encourages the children to keep awake during the seder (see Pes. 109a). This practice of stealing the afikoman is, however, nearly unknown in Se-phardi Jewish communities.

It became a folk custom to preserve a piece of the afikoman as a protection against either harm or the "evil eye," or as an aid to longevity. The power attributed to this piece of mazzah is based on the assumption, in the realm of folklore rather than law, that its importance during the seder endows it with a special sanctity. Thus, Jews from Iran, Afghanistan, Salonika, Kurdistan, and Bukhara keep a portion of the afikoman in their pockets or houses throughout the year for good luck. In some places, pregnant women carry it together with salt and coral pieces, while during their delivery they hold some of the afikoman in their hand. Another belief is that this special mazzah, if kept for seven years, can stop a flood if thrown into the turbulent river, and the use of the afikoman together with a certain biblical verse is even thought capable of quieting the sea. At the seder Kurdi Jews tie this mazzah to the arm of one of their sons with this blessing: "May you so tie the ketubbah to the arm of your bride." Sephardi Jews in Hebron had a similar practice. In Baghdad someone with the afikoman used to leave the seder and return disguised as a traveler. The leader would ask him, "Where are you from?" to which he would answer, "Egypt," and "Where are you going?" to which he would reply, "Jerusalem." In Djerba, the person conducting the seder used to give the afikoman to one of the family, who tied it on his shoulder and went to visit relatives and neighbors to forecast the coming of the Messiah.

AFRICA

The propinquity of the land of Israel to the African continent profoundly influenced the history of the Jewish people. Two of the patriarchs went down to *Egypt; the sojourn of the children of Israel in that land left an indelible impression on the history of their descendants; and the Exodus from Egypt and the theophany at Sinai, in the desert between Africa and Asia, marked the beginning of the specific history of the Hebrew people. Later, in the time of the judges and the monarchy, Palestine was periodically occupied by the Egyptian pharaohs, especially after Thutmose 111, in their attempts to extend their influence northward. Important Egyptian archaeological remains have been found throughout Erez Israel, testifying to indubitable Egyptian influences in the background, literature, and language of the Bible. After the destruction of the First Temple in 586 b.c.e. some of the survivors took refuge in Egypt and the Jewish military colony at *Elephantine; ample records which survive from the Persian period seem to have originated at about this time. This settlement at Elephantine marked the beginning of the extension of Jewish influences toward the interior of the continent, and in all probability it was not the only colony of its kind.

Intensive Jewish settlement in Africa began after the conquests of Alexander the Great in the fourth century b.c.e. For the next hundred years or more, Erez Israel was intermittently under the rule of the Egyptian Ptolemies, alternating with the Syrian Seleucids; the country naturally gravitated toward Africa economically as well as politically. Moreover, in the course of their periodic campaigns north of the Sinai Peninsula the Ptolemies deported some elements of the local population to the central provinces of their empire, or brought there prisoners of war as slaves. According to ancient tradition, Alexander had specifically invited Jews to settle in his newly founded city of ^Alexandria, and it is certain that early in its history they formed a considerable proportion of its population. Before long, Alexandria became a great center of Jewish culture expressed in the Greek language and largely in terms of Greek civilization culminating in the *Septuagint translation of the Bible and in the allegorical writings of *Philo. It is significant that inscriptions found near Alexandria provide the earliest positive evidence of the existence of the synagogue as an institution. From Egypt the Jewish settlement spread westward along the North African coast reaching *Cyrene at least as early as the second century B.c.E. According to some scholars, Palestinian Hebrews had reached further west long before this, as early as the days of the First Temple, accompanying and helping the ^Phoenicians in their expeditions and playing an important role in the establishment of the Punic colonies, including *Carthage itself. It is further suggested that these settlers had a considerable influence in the interior of Africa and were ultimately responsible for the vaguely Jewish ideas and practices that may still be discerned in certain areas. In any case, in the Roman imperial period there were Jewish settlements throughout the Roman provinces as far west as the Strait of Gibraltar. In some areas the Jewish colonies were of great numerical importance and were able to play an independent political role. In Egypt the friction between the Alexandrian Jewish colony and its neighbors was so marked that it developed into a perpetual problem and seems almost to have anticipated the i9th-century antisemitic movement. After the fall of Jerusalem in 70 c.e, *Zealot or Sicarii fugitives from the Palestinian campaigns fled to Egypt, where they instigated a widespread revolt among the Jewish population. The rebels succeeded in dominating large stretches of the countryside, though they were unable to capture the fortified cities. A similar revolt on a smaller scale, about which less information has survived, seems to have occurred simultaneously in Cyrene.

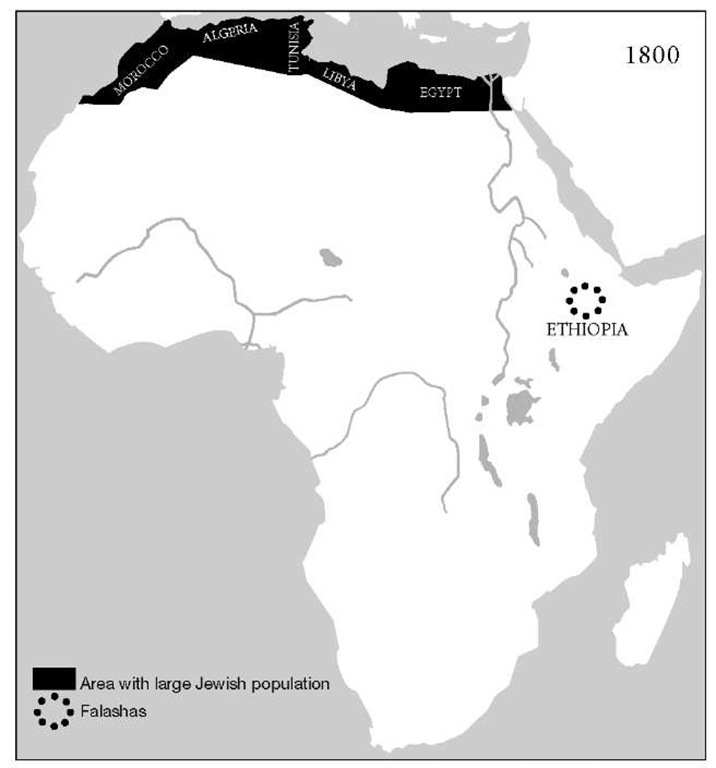

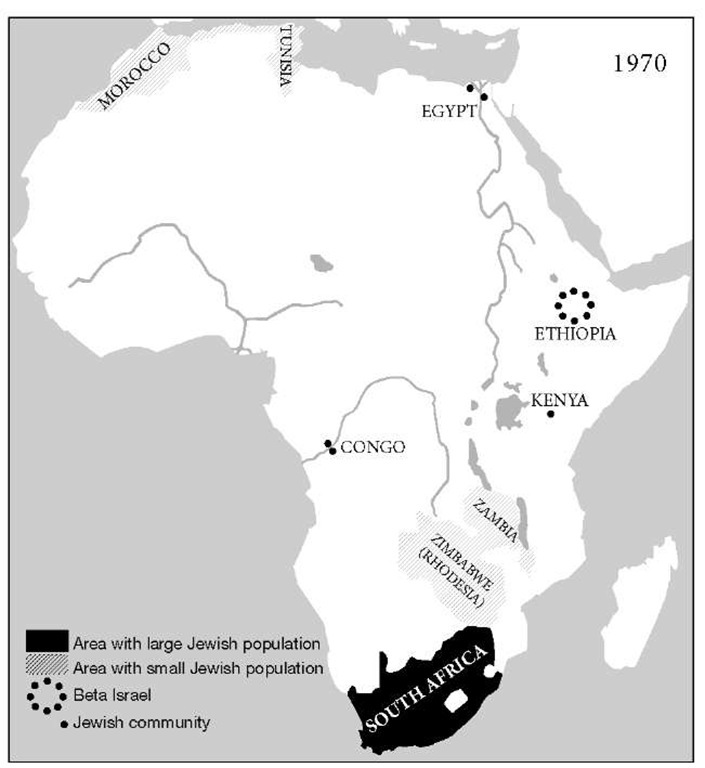

Main concentrations of Jewish population on the African continent at different periods.

Although swiftly subdued by the Romans, these outbursts were soon followed by the Great Revolt of 115-7 all along the North African coast, at least as far as Cyrene, as well as in Cyprus and Mesopotamia. This revolt, organized apparently by some directing spirit of real genius, momentarily achieved sweeping success, with the insurgents dominating Cyrene and large tracts of the Egyptian countryside. It was, however, bloodily suppressed, and the Jewish settlements in the area of revolt never fully recovered from this blow. When Christianity was adopted as the official religion of the Roman Empire, Judaism was at a further disadvantage. Force as well as blandishment was exerted against the Jews; there were bloody anti-Jewish riots in Alexandria, and the significance of North African Jewry for a time waned almost to vanishing point. When in the sixth century the Byzantines reoccupied the former Roman provinces of North Africa, organized Jewish life was systematically suppressed. On the other hand, Jewish influence during the preceding period had not been restricted to the coastal strip, or to persons of Jewish birth. There is some evidence that suggests conscious proselytizing efforts by the Jews in the African interior, or at least extensive imitation of Jewish rites and beliefs there. Traditions of Jewish origin and traces of Jewish practice are to be found among Berber tribes and black peoples well into the continent and it may well be that the *Beta Israel of Ethiopia survive as testimony to a proselytizing activity that once attained considerable proportions. The curious tales told in the ninth century by the Jewish traveler *Eldad ha-Dani of independent Jewish tribes apparently in the African interior, may be a romanticization of what he had actually seen and experienced. The Arab invasions of the seventh century seem to have found only very small scattered Jewish communities along the African coast. The story of the "Jewish" Berber queen Dahiya al-Kahina seems to be largely legendary although it may be that at that time a woman ruled over a Judaizing Berber tribe. After the Arab conquest these communities were revived and probably reinforced by new immigrants, mainly from Asia, who accompanied the Arab conquerors, or who came to take advantage of the new economic opportunities. The new communities were completely Arabized in language and social life; hardly an echo or trace of the previous Greco-Roman Jewish culture can be discerned among them. The newly founded city of Fostat (Old *Cairo) became the largest Jewish center in Egypt; further west *Kai-rouan in *Tunisia was of primary importance and, indeed, from the eighth to the 11th centuries was perhaps the greatest center of rabbinic culture outside Babylonia. The documents found in the Cairo Genizah make possible a reconstruction of the economic, social, and religious life of the Jews throughout this area in graphic detail. It is significant that in the ninth century *Saadiah Gaon, who may be credited with the revitaliza-tion of Jewish scholarship in Mesopotamia, was born, and apparently educated, in the Fayyum district of Egypt. The work of the physician and philosopher Isaac *Israeli, who lived in Kairouan, typified the contribution that the Jews of this area made to contemporary science.The condition of the Jews in Africa under Muslim rule was generally favorable, subject to the usual discriminatory provisions of the Islamic code, which were sporadically enforced; there was a surge of violent persecution in Egypt in the early 11th century, but it was an isolated episode. The triumph of the fanatical, unitarian *Almo-had rulers in the 12th century proved disastrous to the Jews; the practice of Judaism was prohibited in *Morocco and the neighboring lands, and they were forcibly converted to Islam.

The result was that for a long time Judaism could be observed only in clandestine circumstances.

A considerable number of Jews, including the family of Moses *Maimonides, migrated east, making Egypt a major center of Jewish cultural life. After the Almohad domination ended, Jewish life in northwest Africa recovered slowly, but on a restricted and culturally retrograde scale. The wave of massacres and expulsions in Spain and the Balearic Islands in 1391 resulted in a large migration across the Strait of Gibraltar; first there were refugees from these onslaughts and later, on a larger scale, those who had been baptized by force and now desired to revert to Judaism. Thus, especially in the coastal towns of what was later called *Algeria, alongside the old established, quasi-native "Berber" communities, fresh "Spanish" colonies with their own rites and traditions and of a far higher cultural standard arose. The number of Spanish (and later Portuguese) fugitives reaching Africa, primarily Morocco, again increased after the expulsion from Spain in 1492. Their sufferings at the hands of marauders and rapacious local rulers were sometimes appalling. However, in the end they were able to adjust themselves, and henceforth a well-organized Spanish-speaking community, observing the religious regulations provided by "* takkanot of Castile," dominated Jewish life as far east as Algiers. Further along the Mediterranean coast and in the interior (exceptin the largest towns), the Spanish element was less significant.

The Jews generally continued to live under the universal Muslim code, in many places compulsorily confined to the Jewish quarter, their lives hemmed in by discriminatory regulations. They were often compelled to wear a distinctive garb, they had to show respect to Muslims in the street, and they were excluded from certain occupations. On the other hand they were at least allowed to reside at will, except in one or two "holy" cities such as Kairouan, and the periodic Christian incursions on the coastal towns frequently entailed disaster for them. In the ports especially, the Jews played an economic role of great importance, and, with their linguistic versatility, were the principal intermediaries for transactions with European merchants. Occasionally, Jews were dispatched as ambassadors or envoys to the European powers. Sometimes, a person of outstanding ability would become minister of finance or even vizier, wielding much influence until the disastrous fall which was generally in store for him, sometimes involving his coreligionists as a body.

This description characterizes the history of the Jews almost throughout the Barbary States from the 16th century until well into the 19th. Conditions were somewhat but not conspicuously better in the areas farther east, particularly in Egypt, especially after the establishment of Turkish rule at the beginning of the 16th century. It was only with the introduction of European influences, beginning in Algeria in 1830 and culminating in Morocco and Tripolitania after 1912, that the North African Jews were relieved to a great extent of their medieval status. Nevertheless, except in Egypt and some coastal towns, the process of modernization within the communities was slow. On the other hand, in the upper classes the outward occiden-talization of the Jews in language and social life became very marked, while the French administration in Algeria formally recognized the Jews as a European element, the *Cremieux decree in 1870 giving Algerian Jews French nationality.

Meanwhile occidental Jews had established themselves in areas of European settlement at the southernmost tip of the African continent. Isolated settlers are recorded here in the early 19th century; a community largely of English origin was founded in *Cape Town in 1841, spreading from there to other places. The Kimberley diamond field, which opened in the 1860s, was a considerable stimulus to new settlement. With the discovery of gold in Transvaal in the 1880s many Jews emigrated there from Eastern Europe, founding important communities in and around ^Johannesburg. After World War 1, immigration, especially from Lithuania, assumed relatively large proportions, and the *South African Jewish community of some 100,000 was among the most affluent in the world. From South Africa the Jewish settlement spread northward into Rhodesia (^Zimbabwe), as soon as that territory was opened up in the 1890s. During the period between World War 1 and World War 11 there was a Sephardi influx as well, mainly from Rhodes, which spread to the Belgian *Congo. There were also small European Jewish colonies in the British East African territories, joined by immigrants from Egypt and even Yemen.

The Vichy regime in France during World War 11 brought a temporary setback in Jewish status in the French-dominated areas of North Africa and the revocation of the Cremieux decree. The subsequent Nazi military occupation had distressing, although not enduring, consequences. The European withdrawal from Africa after World War 11, coupled with economic changes in that continent, profoundly affected the Jewish communities, all the more so with the wave of anti-Jewish feeling that spread throughout the Arab world after the foundation of the State of Israel. A large portion of the Jewish community of Tunis and almost the whole Jewish community of Algeria left (mostly for France) when the French period of domination ended. The changed circumstances resulted in the migration also of the Jews of Egypt and Cyrenaica, in great part to Israel. Aliyah to Israel, immigration to France, and other countries also reduced the Jewish settlement in Morocco, numerically the largest in Africa, to one-fifth of its former number, approximately 50,000 in 1969; political conditions there did not deteriorate formally. The only part of the continent in which the Jewish communities did not initially diminish was South Africa, although gradually with the end of apartheid the community dropped significantly in numbers. By 2005 the community had fallen to about 75,000 with some 1,800 Jews a year emigrating to other countries largely because of the dramatic rise in violent crime.

The most remarkable example of Black Judaizing movements is to be found in South Africa and Zimbabwe among the *Lemba tribe, and there are similar movements throughout the continent which range from movements which depend on perceived shared origins – sometimes invoking the myth of the *Ten Lost Tribes of Israel – to movements of conversion such as the *Bayudaya in Uganda.

The establishment of the State of Israel brought a renewal of the movement to bring the *Beta Israel of Ethiopia into closer relations with world Jewry. The State of Israel also established cordial relations with the emergent African states, entering into diplomatic relations with them and sending economic, military, and agricultural experts to assist them in solving their problems (see *Israel, Historical Survey, Internal Aid and Cooperation). However, under pressure from the Arabs after the Yom Kippur War of 1973, 29 African countries broke off diplomatic relations with Israel, though in the course of the years, starting with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) in 1982, most reestablished relations.

AFRICA, NORTH: MUSICAL TRADITIONS

Geographically, North Africa (the countries of the Maghreb, i.e., Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya) belongs to Africa, but culturally it is a part of the Islamic world. Some scholars have set up a twofold division of the entire area: the musical culture of the coastal region and that of the interior, roughly corresponding to "urban" and "rural," or "Andalusian" (i.e., Spanish-influenced) and "Berber" (i.e., autochthonous) music. Neither of these areas however, is homogeneous, and there are sometimes considerable differences in musical style between one coastal or interior district and another. North Africa is therefore a musical crossways of many traditions: old Mediterranean, Berber, Bedouin, Near Eastern (including Turkish, and recently Egyptian), Andalusian (or "Moorish"), and Saharan. Not all of these are present at the same place and time, and often one is faced with stylistic blends, which are difficult to define.

The Jews, historically among the oldest elements of the population, have taken an active part in each stage of the area’s musical history. They have also preserved more elements from older traditions, with the conservation typical of "fringe cultures," and, in addition, have absorbed still other outside influences through factors in their own history. Both before and after the appearance of Islam there was close and permanent contact with Palestinian, Babylonian, and Egyptian Jewry. During the reconquista and after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, Spanish, Portuguese, and later also Italian Jews settled in North Africa. The musical usages of the immigrants were influenced by the local ones and influenced them in return. This blending of styles and openness to influence has remained typical of North African Jewish music.

Thus, the musical traditions and practices of the North African Jews represent a conglomerate of a variety of old and new, sacred and secular, folk and art, local and shared musical styles. One can also add the advent of recent innovative stylistic blends representing the attempt to modernize the old tradition. Interestingly, talented Jewish musicians in all four countries were intimately involved in the creation and promotion of the new styles. As a rule, one can state that the musical traditions and practices of the North African Jews are interconnected in various ways with those of the non-Jewish environment. However, comparisons between the Jewish and non-Jewish musical styles are particularly difficult to make, since each is in itself a complex of historical and cultural entities, not to mention the serious obstacles characterizing any other oral tradition – the lack of musical documents and the lack of accuracy in oral transmission. This makes it impossible to state what derives from a Jewish and what from an Arab source. Nevertheless, one can speak of certain specific traits.

It seems nevertheless that the distinguishing traits should be essentially sought in the linguistic, thematic, and functional particularities. First and foremost are the musical rendering of biblical readings and prayers, and the singing of liturgical Hebrew poems, piyyutim, written by the most famous poets of the Jewish people as well as by locally distinguished ones. These include hymns of praise, supplications, lamentations, and the celebration of holidays. The French specialist in Moroccan music, Alexis Chottin, mentions the remarkable fact that when Hebrew texts are adapted to replace the original, they maintain the Arab metric and prosody, which, he points out, is not translation. In addition to the setting of the borrowed melodies to Hebrew texts, this type of arrangement usually leads to melodic and rhythmical changes, so their functional use in Jewish-specific circumstances may be considered as factor highlighting their Jewishness. A special category of bilingual poetry called matruz (combined Hebrew and Arab verses and strophes) should also be noted. The question of Jewishness in the Oriental music appeared in connection with the intriguing phenomenon which arose from the broad-based ethnic movement of the 1980s in Israel. Challenging the widely held belief that Oriental musical traditions have a folk and indigenous background, representatives of the latter responded by arguing that the erudite mystical-religious ceremonial music known as *bakkashot, should be placed on the same level as western classical music.

The singing of bakkashot and piyyutim always refers to North African classical music, which, itself, is identified with the Andalusian compound and multi-sectional form of the nuba in all of the African centers. Established in Spain, the basic components and characteristics of the Andalusian nuba have survived in the major traditions of Fez, Tlemcen, Algier, and Tunis where they are called respectively: ala, gharnatt, sana, and ma’luf. Some differences notwithstanding, they are very similar in spirit and structure. The individual nuba is named after the mode or tab" (nature or temperament); for example nuba dtl, nuba rasd, etc. The overall physiognomy of the nuba in all centers is more or less alike: it comprises an instrumental prelude or preludes and a series of pre-composed vocal pieces that represent autonomous phases of the nuba, each having its own set of poetic texts as well as melodic and rhythmic characteristics. Most of the poems sung in this repertory consist of muwashshahat and free-measured pieces that intersperse the various phases. The overall structure as well as the individual phases are governed not only by modal unity but also by rhythmic acceleration that reaches its peak toward the end of the nuba.

Morocco

Travelers who record their impressions usually display exceptional intellectual curiosity and their observations can supply important evidence. By an extraordinary coincidence, three different travelers recorded their impressions of wedding ceremonies held in the same community of Tangier: the Jewish Italian writer Samuel *Romanelli in 1787; the French painter Delacroix in 1832; and the French author Alexandre Dumas in 1832. All three travelers describe Jewish women dancing, and the traditional group of three musicians, which accompanies the dancing and singing: the ‘ud (the classical Arab short-necked lute), the kamanja (short-necked bowed lute) or the modern violin which has come to be its substitute, the darbuka (pottery vessel-drum) or the tar (frame drum). The kamanja or violin is played in the medieval fashion, with the body of the instrument resting on the knee. Delacroix, who also recorded in his journal that the Jewish musicians of Mogador were the best in all Morocco, depicted this traditional ensemble along with a dancer. Romanelli records that the instrumentalists, poet-singers, and preachers were remunerated in two ways. In the synagogue, the intended payment was only announced out loud, but outside the synagogue the coins were immediately put on the instrument or on the performer’s breast.

Jewish musicians also distinguished themselves as entertainers in local gentile society, either in company with Muslim musicians or as special "Jewish bands." One folktale tells how such a Jewish ensemble was commanded to give a concert before the sultan on the Ninth of Av (see *Av, Ninth of). Since they could not refuse to appear, they played the melodies of the traditional *kinot, and henceforth were known as "The Singers of Woe."

The art of the paytan (religious poet, and by extension, singer of religious poetry) is also rooted strongly in the Anda-lusian tradition. In almost every synagogue there is a paytan in addition to the hazzan. His principal task is to sing prayers such as Nishmat and *Kedushah, and all the piyyutim. A paytan may take part in the performance of the bakkashot, but not every paytan possesses the necessary knowledge for this special art, so that a vocally and musically gifted layman will often function as the "leader" there. Since the bakkashot were performed early on Sabbath mornings, the instrumental part is completely avoided. As a result, the singers evolved the habit of adding passages sung to the syllables na na na in which the role of the accompanying instrument is thus imitated. These syllables and the wealth of vocalizes (textless ornamented phrases) is in fact a remarkable feature of the North African art of singing. When the bakkashot and piyyutim are sung on a weekday, they are usually accompanied by the traditional instrumental ensemble.

In the realm of folk music one should mention the folk tradition of group performance, especially in the Atlas Mountain regions, often in the form of women’s ensembles. Their music and dances are not different from those of the Berber tribes.

Music plays an important role in the pilgrimage festivals at the numerous hillulot (sing. *hillula). It marks and enhances the celebration of a revered public figure and the mass pilgrimage to the site of his burial, which, in some cases, is venerated by both Jews and Muslims. The ritual of sainthood is deeply entrenched in all strata of the people.

A special Moroccan custom is the tahdtd, a ceremony conducted the night before circumcision when it is believed that the newborn, subject, prior to circumcision, to harm by evil forces, is at the highest vulnerability. In this event a sword is used to banish the evil spirits while a selection of appropriate biblical verses is chanted.

Another well-known celebration marked by singing and dancing is the *Maimuna (which has been transferred to Israel). At these gatherings many original creations of the qastda type can be heard. The qastda, a popular song in Hebrew or in the vernacular, is sung both by the educated and the lower classes. Some qastda songs are anonymous and well-known poets created others. In the framework of the bakkashot were introduced dozens of qastdas composed by local poets borrowing their tunes from Arab qastdas. Their texts include praises of the saints, ethical and religious subjects, and comments on historical and present or recent events. They are sung with or without accompaniment, and the tunes are mostly adaptations of well-known melodies. Such qastda songs are found in all North African countries. One of the most talented poets of this genre was David Elkayim (1851-1940), and among the most celebrated paytanim were David Hasin (1727-1792), David Iflah, and David *Buzaglo (1903-1975).

Tunisia

The first and earliest documents focusing on the eternal debate concerning the permissibility of music are the two responsa of *Hai Gaon to questions addressed by representatives of Tunisian Jewry. One of them, perhaps addressed to the community of *Kairouan, forbids the hazzanim to sing poems in the "language of the Ishmaelites," even at banquets. Another one, often quoted in later literature, is addressed to the community of *Gabes, and discusses whether the traditional prohibition (Git. 7:1) against singing with instrumental accompaniment and which restricts all secular songs in memory of the destruction of the Temple also applies to wedding celebrations. Hai Gaon approved of singing pious hymns of praise on such occasions, but secular Arab love songs were strictly forbidden, even without accompaniment; "and so to what you have mentioned … that women play the drums and dance [at such festivities], if this is done in public there is nothing more grave; and even if they … only sing, this is most unseemly and forbidden." The free and unsegregated participation of women singers in wedding festivities, family rejoicings, pilgrimages to saints’ tombs, and their prominence as professional mourners, were probably related to similar usages in Berber society and have survived until the present.

The Tunisian term la’b (lit. amusement but used for dancing) is mentioned in two *Genizah documents: in one, the birth of a boy in Fostat, Egypt, is celebrated with la’b by his family at Mahdia in Tunisia; in another, a poor Tunisian teacher alludes, surprisingly, to la’b at the burial of his son.

In proximity to Gabes lay the famous Island of *Djerba, home to a quite old Jewish community. It was there that in 1929 Robert *Lachmann carried on important fieldwork research with the hope of disclosing in their liturgical cantillation older stratum of Jewish music. His important analytical study of this tradition was published after his premature death (see Bibl.).

The output of piyyutim and songs the Jewish poets wrote in Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic is considerable and played an important educative and socio-cultural role. They cover numerous song genres and themes related to Jewish life.

Toward the end of the 19th century and during the first decades of the 20th Jewish musicians played an essential role in the indigenous cultural reform movement as well as in the crystallization of a new musical style. They were involved in the growth of the cinematographic and record industries and the introduction of the modern Egyptian musical style, and distinguished by the remarkable involvement of numerous talented female musicians. Some of those female musicians established their own cafe-concert halls, which attracted numerous Jewish and non-Jewish music fans. Leila Sfez, who owned a popular cafe-concert hall, was the aunt of the legendary actress and singer H biba Msika, whose tragic premature death was the subject of a film produced by the Tunisian Slama Bachar. Interestingly, the first records of Tunisian music, published in 1908, included the interpretations of the Jewish female musicians: Louisa the Tunisian, and the sisters Semama, Fritna, and Hbiba Darmon.

In an article dedicated to Jewish musicians published in 1960, the Tunisian author All Jandubi warmly extolled the valuable contribution they made to Tunisian music and musical life. He mentions the special skills of many famous Jewish female and male musicians, including a few of Libyan origin. Among the famous singers and instrumentalists he mentions are Isaac, Abraham Tibshi, Khaylu al-Sghir, Mri-dakh Slama and his son Sousou, Gaston Bsiri, H biba Msika, and Raoul Journo.

In 1928, the Jerusalemite cantor, paytan, and composer Asher Mizrahi arrived in Tunis, staying until 1967, the year of his return to Israel. He soon became a dominant figure, particularly in the realm of synagogal and paraliturgical music, thus enriching the musical life of the community.

Algeria

Following the riots against the Jews in Spain in 1391, a wave of refugees found shelter in Algeria. Among the newcomers was the rabbinic authority, philosopher, and kabbalist Simeon ben Tzemah *Duran (b. Majorca, 1361), who was elected chief rabbi of Algeria in 1408 and died in 1444. Duran was the author of a comprehensive book, Magen Avot, which deals with religious philosophy and diverse sciences, including an important section on the science of music. In addition to generalities he wrote on music, its nature and influence, the bulk of his exposition concerns the biblical accents, which are "genera of melodies," extolling their importance for the understanding of biblical texts and their rhetoric-musical meanings. Regarding the melodies used for the piyyutim, he tends to admit that they were adopted from other nations.

We find years later interesting and unique evidence of the involvement of Jewish musicians in indigenous music. It occurs in the book of a young Russian pianist, Alexandre Christianowitch (1835-1874): Esquisse historique de la musique arabe, published in 1863. The author, an officer in the czar’s navy, was compelled, for reasons of health, to stay in Algiers. For two years he did research on the local classical music. He reports that his first encounter with indigenous music took place in a Moorish cafe-concert hall where he heard a group of Jewish musicians, and that later on his Muslim mentor was critical concerning the authenticity of the classical music played by the Jews. This is, however, not the case in recent Muslim sources, which, on the contrary, warmly extol the role played by Jewish musicians such as Maalem Benfarachou, Laho Seror, and Mouzinou in the preservation of the old classical Andalusian tradition. This approach characterizes in particular the book of Algerian musicologist Nadya Buzar-Kasb-adji: L.Emergence artistique algerienne au xxe siecle (published in 1988).The author describes him as "an outstanding personage who has been the pivotal actor in an artistic Renaissance movement wherein Arab-Andalusian music constituted the leaven." She adds that Yafil remained faithful to the Arab-Andalusian tradition, which connected Jews and Arabs, endowing them with a feeling of common identity. Yafil also founded in 1911 the al-Moutribiyya music society, most of whose members were Jewish musicians.

Like their Moroccan, Tunisian, and Libyan Jewish colleagues who immigrated to France, Jewish Algerian musicians pursued a successful career in their new environment, often in close collaboration with non-Jews. This is, for instance, the case with the blind female singer and ‘ud player Sultana Da’ud, alias "Reinette l’Oranaise," who, after she achieved remarkable success in Algeria, continued to be admired by her numerous fans in France for her expressive and poignant art. Samples of her repertory were issued in several cassettes and CDs. Another example is the recent comeback of the popular singer Enrico Massias to the classical music of Algeria. This occurred after the assassination of his master and father-in-law, the celebrated Jewish musician Raymond Leiris.

![tmp129-24_thumb[1] tmp129-24_thumb[1]](http://what-when-how.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/tmp12924_thumb1_thumb.jpg)