ADLER, RICHARD

(1921- ), U.S. composer, lyricist. Bronx-born Adler, the son of a classical pianist-teacher, Clarence Adler, graduated from the University of North Carolina and served as a lieutenant (jg.) in the U.S. Navy during World War 11 before concentrating on composing. He began collaborating with Jerry Ross, also Bronx-born and Jewish, in 1950 and had a popular success with the song "Rags to Riches." But their first Broadway musical, The Pajama Game, in 1954, brought them recognition for the way the songs worked with the plot and for their integration of American speech idioms. The show, about a labor-union conflict and the threat of a strike in a pajama factory, was directed by the venerable George Abbott and also launched the career of Harold *Prince as a producer and established Bob Fosse as a major choreographer. Jerome *Robbins was hired as a backup in case Fosse did not work out. The show had hit songs like "Hernando’s Hideaway," "Hey There" and "Steam Heat." The next year Adler and Ross gave Broadway Damn Yankees, a musical comedy version of the Faust story, with such songs as "Whatever Lola Wants" and "(You Gotta Have) Heart." But Ross died that year, at the age of 29, of a bronchial infection and Adler began to work alone.

Adler had little commercial success with Broadway musicals in the 1960s and 1970s but his symphonic works, including "Yellowstone Overture"; "Wilderness Suite," commissioned by the Interior Department for full orchestra to celebrate the wilderness park lands; and "The Lady Remembers," commissioned by the Statue of Liberty / Ellis Island Foundation to celebrate the statue’s centennial, also for full orchestra; and his ballets were performed widely and won awards. He also achieved success at composing musical commercials ("Let Hertz Put You in the Driver’s Seat") and earned himself the sobriquet "king of the jingles." Adler was also called on to produce shows to mark celebrations and stage entertainments for inaugural galas. Perhaps his most celebrated show was produced on May 19, 1962, when Marilyn *Monroe sang "Happy Birthday" to President John F. Kennedy during a birthday salute at Madison Square Garden. Adler won two Tony (theater) awards and four Pulitzer Prize nominations; he was a member of the Songwriter’s Hall of Fame.

In later years, Adler turned to a form of meditation called Siddha Yoga, which he said helped him deal with the grief when his son died of cancer at the age of 30 and when he himself battled throat cancer.

ADLER, SAMUEL

(1809-1891), rabbi and pioneer of the Reform movement. Adler, born in Worms, was the son of Rabbi Isaac Adler, who gave him his early education. He received a traditional education at the Frankfurt Yeshivah and studied privately with Rabbi Jacob Bamberger. He also received a secular education at the University of Bonn and Giessen, where he studied philosophy and especially Hegel under Joseph Hillebrand. He officiated as preacher and assistant rabbi at Worms, and in 1842 was appointed rabbi of the Alzey (Rhenish Hesse) district. Adler was one of the early protagonists of Reform and took part in the rabbinical conferences of 1844-46 (see *Reform Judaism). He worked strenuously for the improvement of Jewish education and the removal of legal disabilities affecting Jews. He believed that rituals had to be changed to fit contemporary circumstance and worked on improving the status of women in Jewish education and in prayer. In 1857 Adler went to America as rabbi of Congregation Emanu-el in New York, succeeding Leo *Merzbacher. A classic reformer, he rejected supernatural revelation and the authority of the law. He omitted references to the return to Zion in the prayer book and during the parts of the service that were not devotional, head covering was removed at Emanu-El. He published a revised edition of its prayer book in 1860, and in 1865 helped form a theological seminary under the auspices of his congregation. He was also one of the founders of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. Adler’s interests were scholarly, and he appears to have exercised little influence on the community. In 1874 his congregation resolved on his retirement and appointed him rabbi emeritus. When the Central Conference of American Rabbis was established (1889), Adler was made honorary president. Among his publications are A Guide to Instruction in Israelite Religion (1864) and a selection of his writings, Kobez al Jad, was published privately (1886). An English translation of Adler’s memoirs was published privately by A.G. Sanborn (1967). His son Felix was presumed to be his successor but left the rabbinate to found the Ethical Culture Society and therefore take his father’s ideas to the next stage of their evolution where the particularity of Jews and Judaism are no longer necessary.

ADLER, SAMUEL M.

(1898-1979), U.S. painter. Born in New York City, Adler began drawing as a child. His parents saw the life of an artist as a challenge and thus did not encourage his interest. Nonetheless, at the age of 13 – several years earlier than typical admissions – Adler began artistic training at the National Academy of Design in New York. A talented violinist as well, he supported himself by playing in various venues, from weddings to symphonies. Before graduation Adler left the Academy, dedicating himself to music full time.

In 1933 Adler returned to painting. His first one-man show was not until mid life, when he had a 1948 exhibition at the Joseph Luyber Galleries in New York. This exhibition showed only his current work as two years previously he had destroyed all but two of his paintings. Overnight, critics lauded Adler as an important contemporary artist. Within the year he was teaching art at New York University and from this period on his works were displayed at, and acquired by, various venues in New York and elsewhere.

While Adler grew up with little religious training, he turned to depictions of the Jewish experience when he entered the art world. He created dozens of paintings of rabbis, including White Rabbi (1951), which shows a young rabbi in a tallit and kippah standing in front of Sabbath candles. In this work, and others, one can see the influence of Amadeo *Modigliani’s simplified, symmetrical approach to the human figure. Adler always kept the human form at the center of his art, even as he moved away from representational painting to more abstract collages.

Adler discussed his view of Jewish art in a 1964 public lecture: "I believe in a dimension in every work of art that lies beyond the measurables, an inexplicable, a quality of life we call presence, that cannot be construed as either Jewish or Christian."

ADLER, SAUL AARON

(1895-1966), Israeli physician and parasitologist. Adler was born in Karelitz, Russia, but was taken to England as a child of five. He studied medicine at Leeds University and specialized in tropical medicine at the University of Liverpool. During World War 1 he served as a doctor and pathologist with the British armies on the Iraqi front. Between 1921 and 1924 he did research on malaria in Sierra Leone. In 1924 he made his home in Jerusalem and joined the staff of the Hebrew University Medical School. Four years later he was appointed professor and director of the Parasitological Institute of the university. Adler translated Darwin’s Origin of Species into Hebrew.

Under the auspices of the British Royal Society, he organized a number of scientific expeditions in the countries and islands of the Mediterranean. He specialized in the etiology and pathology of tropical diseases, the ways in which parasites pathogenic to man and animals are spread, and the immunology of protozoan infections. Adler introduced the Syrian golden hamster (brought to the Hebrew University from Aleppo by Israel *Aharoni) into experimental medicine. His work on malaria, cattle fever, leprosy, and dysentery, and his pioneer research into the Leishmania diseases (the Jericho and kala-azar groups) and their carriers, the sandflies, won him an international reputation. In 1933 Adler was awarded the Chalmers Gold Medal of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene for his work on the transmission of kala-azar by the sandfly. In 1957 he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society.

ADLER, SELIG

(1909-1984), U.S. historian. Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Adler graduated from the University of Buffalo in 1931. He was appointed to the history faculty of the University of Buffalo in 1938 and subsequently named Samuel Paul Capen Professor of American History at the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1959. He specialized in American diplomatic and American Jewish history. His Isolationist Impulse (1957) is a study of isolationist thinking in the United States between the two World Wars. American Foreign Policy Between the Wars (1965) is a judicious, widely accepted account of that contentious subject. From Ararat to Suburbia: A History of the Jewish Community of Buffalo (with Thomas E. Connolly; 1960) is one of the most extensive and exact histories of any Jewish community. He was also the archivist for the Buffalo Jewish community archives that bear his name, which are located in the Butler Library at Buffalo State College. Active in Jewish communal and cultural affairs, Adler was a member of the New York Kosher Law Advisory Board and of the executive board of the American Jewish Historical Society.

ADLER, SHALOM BEN MENAHEM

(1847-1899), rabbi and author. Adler was educated in the home of his uncle R. Hillel *Lichtenstein. In 1869 Adler was appointed rabbi of Szerednye (now Sered, Slovakia), a position he occupied for 30 years until his death. His Rav Shalom, published posthumously by his son-in-law Elijah Sternhell (1902), is distinguished for its inspiring homilies and beautiful style. His unpublished works include novellae on the Talmud and responsa. His three sons were all rabbis: Menahem Judah, his successor; Phinehas, the rabbi of Radvancz; and Joab, the rabbi of Tapoly-Hanusfalva, who was born in 1880 and killed by the Nazis.

ADLER, STELLA

(1901-1992), U.S. actress and acting teacher. An exponent of Method acting and probably the leading American teacher of her craft, Adler was born into a celebrated acting family rooted in the Yiddish theater (see *Adler). She made her stage debut at four, appeared in nearly 200 plays, and occasionally directed productions. She also shaped the careers of thousands of performers at the Stella Adler Conservatory of Acting, which she founded in Manhattan in 1949 and where she taught for decades.

Born in Manhattan, the youngest daughter of Jacob Adler and the former Sara Levitzky, Russian immigrants who led the Independent Yiddish Art Company, Stella had five siblings, and they all became actors, notably Luther. Her parents were the leading classical Yiddish stage tragedians in the United States. Stella started on the stage in 1905 at the Grand Street Theater on the Lower East Side in Manhattan. She played both girls’ and boys’ roles and then ingenues in a variety of classical and contemporary plays over ten years in the United States, Europe, and South America, performing in vaudeville and the Yiddish theater. She won acclaim as the leading lady of Maurice *Schwartz, but she sought more versatility. Her work schedule allowed little time for formal schooling.

She was introduced to the Method theories of Konstantin Stanislavsky, the legendary Moscow Art Theater actor and director, in 1925 when she took courses at the American Laboratory Theater school, founded by Richard Boleslavski and Maria Ouspenskaya, former members of the Moscow troupe. Adler’s most frenetic years were with the Group Theater, a cooperative ensemble dedicated to reinvigorating the theater with plays about important contemporary topics. The Group, founded by Harold *Clurman (whom she married in 1943), Lee *Strasberg and Cheryl Crawford, also believed in a theater that would probe the depths of the soul. Both aspects appealed to her and she joined in 1931. She won high praise for performances in such realistic dramas as Success Story by John Howard Lawson and two seminal Clifford *Odets plays, Awake and Sing! and Paradise Lost. She was also hailed for directing the touring company of Odets’ Golden Boy. Recalling her years with the company, she deplored a dearth of good roles for women in "a man’s theater aimed at plays for men." But she credited the company with evoking in her an idealism that shaped her later career. "I knew that I had it in me to be more creative, had much more to give to people," she said. "It was the Group Theater that gave me my life."

Before the Method revolutionized American theater, classical acting instruction had focused on developing external talents. Method acting was the first systematized training that also developed internal abilities, sensory, psychological, and emotional. Strasberg, who headed the Actors Studio until his death in 1982, rooted his view on what Stanislavsky stressed in his early career. Adler went to Paris and studied intensively with Stanislavsky for five weeks in 1934. She found he had revised his theories to stress that the actor should create by imagination rather than by memory and that the key to success was "truth, truth in the circumstances of the play." She instructed: "Your talent is your imagination. The rest is lice." She was a stern taskmaster, believing that a teacher’s job is to agitate as well as inspire. She demanded craftsmanship and self-awareness, calling it the key to an actor’s sense of fulfillment. When students failed to understand roles, she acted them out, insisting: "You can’t be boring. Life is boring. The weather is boring. Actors must not be boring."

She appeared in three films: Love on Toast (1938), Shadow of the Thin Man, and My Girl Tisa (1948). Her later stage roles included a fiery lion tamer in a 1946 revival of He Who Gets Slapped and in London an eccentric mother in a black comedy, Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mama’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feeling So Sad, in 1961. She restated her theories in Stella Adler on Acting, published by Bantam Books in 1988. For her students, who included Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, Warren Beatty, and Candice Bergen, she was both the toughest critic and the most profound inspiration, saying: "You act with your soul. That’s why you all want to be actors, because your souls are not used up by life."

ADLER, VICTOR

(1852-1918), pioneer and leader of the Austrian Social-Democratic party and a prominent figure in the international labor movement. Born in Prague, Adler was taken as a child to Vienna where his father became a rich man and, two years before his death, embraced Catholicism. A physician by profession, Adler devoted his life to the cause of the working class. His greatest political victory was the granting of universal suffrage by the Imperial Government in 1905. He was a member of the Austrian parliament from 1905 to 1918 and foreign minister in the Socialist government of 1918. Adler was a victim of antisemitic agitation and suffered from the ambivalent attitude to Jews on the part of his colleagues at school and university. After his marriage he converted to Christianity "to save his children from embarrassment." During his long political life he was always conscious of his origin but avoided taking a clear stand on Jewish issues. He opposed a debate on antisemitism at a congress of the Socialist International in Brussels in 1891. In later life, free from any religious affiliations, Adler refused to acknowledge the specific problems of the Jewish proletariat and opposed the idea of Jewish nationhood.

ADLERBLUM, NIMA

(1881-1974), author and philosopher. Adlerblum, a daughter of H ayyim *Hirschensohn, was born in Jerusalem but left the city with her parents when she was about 11, moving to Turkey and later to the United States. She studied in Paris and subsequently at Columbia University, where she became closely associated with John Dewey. Her doctoral thesis, A Study of Gersonides in His Proper Perspective (Columbia University Press, 1926), was actually a call for a new approach to Jewish philosophy, which she felt was wrongly assessed by being viewed in its relation to other contemporary philosophies, maintaining that its true main thrust could be detected only when it was examined within its own environment. This conception, she argued, was best expressed by *Judah Halevi (1075-1145) who, in his Kuzari, maintained that Judaism had its own spiritual ideas and ideals, which were intimately bound with the historic experience of the Jewish people. Her attitude coincided with John Dewey’s philosophical theory that the value of abstract thinking depended on its concern with living experience and its fruitful application to life, but her views were challenged and criticized by many scholars.

In her A Perspective of Jewish Life Through Its Festivals (1930) she further expounded her philosophical theory of Judaism, and in her Elan Vital of the Jewish Woman (1934) she stressed that woman’s sensitivity in certain areas was vital and would enrich Jewish scholarship when it was opened up to them. She also published philosophical treatises on medieval Jewish thinkers. Adlerblum served on the international committee for spreading the teaching of John Dewey (outside America), was a member of the American Philosophical Association, and a life fellow of the International Institute of Arts and Letters. She was active in Hadassah from its inception, serving on its National Board from 1922 to 1935.

After an absence of 80 years she returned to Israel. A number of her articles on the vivid impact of her childhood in Jerusalem on her thinking were included in The Jewish Heritage Series edited by Rabbi Leo Jung (New York).

ADLER RUDEL, SALOMON

(1894-1975), social worker. He was born in Czernowitz, Austro-Hungary (now Ukraine). Adler-Rudel was director of the Welfare Organization of Eastern Jews in Berlin (1919-30) and was active in developing welfare services for Jewish migrants from Eastern Europe. As director of the Berlin Jewish community’s department of productive welfare from 1930 to 1934, he contributed to programs to reduce dependence and to increase self-support among welfare cases. From 1926 to 1929 he served as editor of the Juedische Arbeits – und Wanderfuersorge. When the Nazis came to power, he moved to London where he was administrator of the *Central British Fund (1936-45). During World War 11, he was prominent in rescue activities of Jews from Europe. After the war he settled in Erez Israel and was director of the Jewish Agency’s department of international relations. In this capacity, he prepared agreements with the International Refugee Organization and other international migration bodies for the transfer to Israel of the "hard-core" cases in the European Displaced Persons Camps. From 1958 he was director of the *Leo Baeck Institute for German Jews in Jerusalem. In 1959 he published Ostjuden in Deutschland 1880-1940.

ADLIVANKIN, SAMUIL

(1897-1966), painter and graphic artist. Adlivankin was born in Tatarsk, Mogilev province, Russia. As a child, he received a traditional Jewish education. In 1912-17, he studied at the Odessa Art School. In 1916, he became a member of the Odessa Association of Independent Artists and participated in their exhibitions. In 1918-19, Adlivankin studied at the Moscow Free Art Workshops, where his tutor was V. Tatlin (1885-1953). In the constructivist works created by Adlivankin in 1919-20, Tatlin’s influence is clearly manifested. In 1921-23 he joined the New Painters’ Society (nozh) and showed his work at its 1921 exhibition in Moscow. His works of this period feature scenes of everyday Soviet life, treated ironically or satirically and executed in the expressionist manner, sometimes incorporating elements of primitivism. In 1923-28, Adlivankin drew caricatures for various magazines and worked on political posters together with V. Mayakovsky. In the late 1920s he worked for a number of film studios and made set designs for several productions. In the early 1930s, he made several trips to Jewish agricultural communities in the Crimea and Ukraine that inspired several works portraying the life of Jewish kolkhozes and showed them at the exhibition dedicated specifically to this theme, which took place in Moscow in 1936. In the notorious, overtly antisemitic campaign launched in 1949 against "cosmopolitism," Adlivankin, together with other Soviet culture figures who happened to be ethnic Jews, was subjected to severe criticism and distanced from public cultural life until the mid-1950s: his works were not accepted for exhibits, he received no commissions, etc. The first and only one-man exhibition in his lifetime was held in 1961 in Moscow.

ADLOYADA

Purim carnival. The name is derived from the rabbinic saying (Meg. 7b) that one should revel on Purim until one no longer knows (ad de-lo yada) the difference between "Blessed be Mordecai" and "Cursed be Haman." The first Adloyada was held in Tel Aviv (1912) and spread to other communities in Israel. It is celebrated by carnival processions with decorated floats through the main streets, accompanied by bands.

ADMISSION

Legal concept applying both to debts and facts. Formal admission by a defendant is regarded as equal to "the evidence of a hundred witnesses" (bm 3b). This admission had to be a formal one, before duly appointed witnesses, or before the court, or in writing. When the denial of having received a loan is proved to be false, this is regarded as tantamount to an admission that it has not been repaid. Admissions were originally regarded as irrevocable, but in order to alleviate hardships caused by hasty admissions, the Talmud evolved two causes for their revocation; a plea that the person making the admission had not been serious, or that he had had a special reason for making the admission. When partial admission has been made, the admission is accepted and he is bound to take an oath with regard to the remainder. Admissions can also apply to procedural matters; e.g., on the part of a party to an action that he has no witnesses, in which case he cannot subsequently call one.

The formal admission of a debt, or of facts from which any liability may be inferred, is in civil cases the best evidence of such liability (Git. 40b, 64a; Kid. 65b). The requirements of formality may be met: (1) by making the admission before two competent witnesses, expressly requested to hear and witness the admission (Sanh. 29a); (2) by way of pleading before the court, whether as plaintiff or defendant (Sh. Ar., h m 81:22); (3) in writing (ibid., 17); (4) through any of the recognized modes of kinyan ("^acquisition" ibid.); (5) on oath or the "symbolic shaking of hands by the two parties… which is the equivalent of an oath" (ibid., 28; Herzog, Instit, 2 (1939), 103).

While generally the admission must be explicit, in an action for the recovery of a loan, the denial of the loan would amount to an admission of nonpayment which is implicit in the denial (bb 6a; Shevu. 38b); on proof of the loan, the defendant will then be bound by his admission that he has not repaid it. Conversely, where a plaintiff claims that the defendant owes him a certain species of goods without reserving his right to claim also some other species, he is deemed to have admitted that the defendant owes him only the species claimed and no other, and any admission by the defendant that he does owe another species than that claimed, will not avail the plaintiff (bk 35b). The general rule in a conflict between two contradictory admissions is that the explicit prevails over the implicit and the negative (e.g., "I have not acquired property"") over the positive (e.g., "I have transferred my property"; Tosef., bb 10:1; Git. 40b), but an admission presumed to stem from the knowledge of the relevant facts prevails over one possibly made in ignorance of those facts (cf. bb 149a).

As formal admissions were originally irrevocable, they were widely used as a means of creating new liabilities, as distinguished from the mere acknowledgment of already existing ones. Even though recognized as factually false admissions, they were held to bind the person making them (bb 149a), whether by way of gratuitously incurring a new and enforceable obligation (Ket. 101a-102b; Maim. Yad, Mekhirah, 11:15), or by way of transfer (kinyan). The property concerned thus passes from the owner to the person now admitted by him to have acquired it from him, the concurrence of the beneficiary not being required as he was only benefiting by the admission (Git. 40b; Maim. Yad, Zekhiyyah, 4:12). Admissions of this nonprocedural variety are also termed udita or odaita.

With a view to alleviating hardships caused by precipitate admissions, talmudic jurists evolved two *pleas for having them revoked: the plea of feigning (hashtaah) and the plea of satiation (hasbaah). Where a man, not of his own accord but in reply to a question or demand, made an admission, and on being sued maintained that he had not been serious about it and that the admission was not true, an oath would be administered to him to the effect that he had not intended to admit the debt and that he did not in fact owe it (Sanh. 29b). Similarly, a statement of a person that he had admitted debts owed by him, only for the purpose of ostensibly reducing his assets so as not to appear rich was accepted (Sanh. 29b). Neither plea is valid against admissions made in court, or in writing, or by kinyan, or on oath (Sh. Ar., hm 81). As to admissions made in writing, some scholars hold that so long as the deed has not been delivered to the creditor, the admittor may plead that he was not serious or that he wrote it in order to appear poor (Sh. Ar., h m 65:22 and Isserles to Sh. Ar., h m 81:17). A dying man is presumed not to be frivolous on his deathbed, and his admissions are irrevocable (Sanh. 29b), so are admissions made by his debtors in his favor and presence while he is dying (Isserles ibid., 81:2). The public (the community) must be presumed neither to make rash admissions nor to be interested in appearing without means, hence none of the pleas is available against admissions made by or on behalf of the public (lsserles ibid., 81:1). Where only part of a claim is admitted, the admittor will be adjudged to the extent of his admission and be required to take the oath that he does not owe the remainder (Shevu. 7:1). This rule is based on the presumption that no debtor has the temerity to deny his debt falsely in the face of his creditor (Shev. 42b; bm 3a), a presumption which, curiously enough, does not necessarily apply to a debtor denying the whole (as distinguished from a part) of the debt. Where the whole is denied, the oath is administered to the defendant upon the presumption that a plaintiff will not normally abuse the process of the court (Shev. 40b). Where the defendant satisfies the admitted portion of the claim without adjudication, the claim is deemed to be for the nonadmitted portion only and to be denied in whole (bm 4a, 4b). While a part admission must fit the subject matter of the claim (Shev. 38b), it need not necessarily fit the cause of action; thus, the admission of a deposit might fit the claim on a loan (Sh. Ar., h .m. 88:19). The claim of the whole must precede the admission of the part, the admittor who is not yet a defendant being regarded as a volunteer returning a lost object (Sh. Ar., h m 75:3). An admission is not allowed to prejudice the admittor’s creditors: the holder of a bill may not be heard to admit that he has no claim on it, or the possessor of chattel that they belong to somebody else, so as to deprive his creditors of an attachable asset (Kid. 65b; Ket. 19a). Admissions need not relate to substantive liabilities, but may be procedural in nature: thus a party may admit that he has no witnesses to prove a particular fact, and he will not then be allowed to call a witness to prove it, lest the witness be suborned (Sanh. 31a); or, having once admitted a particular witness to be untrustworthy, he will not later be able to rely on his testimony (Ket. 44a). Admissions could be accepted for one purpose and rejected for another, e.g., the admission of a wrongful act would be inadmissible as a *confession in criminal or quasi-criminal proceedings, but could afford the basis for awarding damages in a civil suit. This rule is found to have been applied to larceny (bm 37a; see *Theft and Robbery), to the seduction of women (Ket. 41a; see *Rape), to arson (Solomon b. Abraham Adret, resp. 2:231), to *usury (ibid.), to embezzlement (see *Theft and Robbery), and to breach of trust (Isserles to Sh. Ar., h m 388:8; Yom Tov b. Abraham Ishbili, Ket. 72a); a wife admitting her adultery was held to lose, on the strength of her admission, any claim to maintenance or other monetary benefits, but not her status as a married woman, thus incurring no liability to be divorced or punished (Maim. Yad, Ishut, 24:18). An early authority posed the question whether the injunction, "you shall have one standard of law" (Lev. 24:22), should not be read to prohibit any distinction between civil and criminal law with regard to admissions; the answer is in the negative, because in civil causes it is said: "He shall pay"; but in criminal cases it is said: "He shall die" (Tosef. Shevu. 3:8).

ADMON (Gorochov), YEDIDYAH

(1897-1982), Israeli composer. Admon, who was born in Yekaterinoslav, Ukraine, went to Erez Israel in 1906. From 1923 to 1927 he studied theory of music and composition in the U.S. In 1927 he returned to Palestine and in the same year published his first songs, among them the popular "Gamal Gemali" (Camel Driver’s Song). In 1930 he went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, the French music teacher. For several years Admon was director of the Israeli Performing Rights Society (acum). After spending 13 years in America, he returned to Israel in 1968. Admon was a pioneer in the field of Israeli song. He was one of the first Israeli composers, and one of the earliest to create a new style which served, often subconsciously, as a model for other composers. This style blends four elements: the music of the Oriental Jewish communities, especially the Yemenite and Persian; Arab music; h asidic music; and Bible cantillation. The result is an absolute organic unity. The rhythm of the Hebrew language is also an important factor in Admon’s music. He was awarded the Israel Prize for the arts in 1974. His work includes music for the theater – Bar Kokhba; Michal, Daughter of Saul; and Jeremiah – for piano and violin, and a symphonic poem, The Song of Deborah.

ADMON BEN GADDAI

One of the few civil law judges in Jerusalem whose name is mentioned in talmudic literature (Ket. 13:1-9; tb, Ket. 105a). Admon probably lived in the latter days of the Second Temple, as three of the seven halakhot in his name are supported in the Mishnah by R. *Gamaliel the Elder. Admon and his colleagues received a salary of 99 maneh (1 maneh = 100 denarii) from the Temple treasury. However, due to early variants in mishnaic tradition regarding Admon’s title, his precise judicial function is not clear. He is referred to as either one of the dayyanei gezerot (ni"in ‘J’l "decree judges") or one of the dayyaneigezelot (nlVj? ‘J’l "robbery judges"). On this and similar changes of the Hebrew letters I and V see Epstein, Tarbiz, 1 (1930), n. 3, 131-2.

ADMONI, VLADIMIR GRIGORYEVICH

(1909-1993), Soviet Russian literary and linguistic scholar. A professor at the Pedagogical Institute of Leningrad, he specialized in Germanic and Norwegian languages and literature and in the theory of literary translation. He wrote monographs on Ibsen (1956) and Thomas Mann (1960; in collaboration with T.I. Silman) and on problems of German syntax (1955). He also translated and edited the standard Russian version of the works of Ibsen (4 vols., 1956-58). During the 1964 trial of the young Leningrad Jewish poet Yosif *Brodski, Admoni, who testified for the defense, was ridiculed by the presiding Soviet judge for his "strange-sounding" (i.e., Jewish) name. Have served as personal physician. Another son of Moses was michael or meir (died 1785), prominent in London communal life, and as warden of the Great Synagogue, one of the original members of the *Board of Deputies of British Jews. john (1768-1845), historian and lawyer, grandson of Joy, was author of History of England from the Accession of King George 111 to the Conclusion of Peace in 1783 (3 vols., London, 1802). His mother was Christian and he was out of touch with the Jewish community. However, he was caricatured by Crui-kshank as a Jew. Originally a solicitor, he became a barrister in 1807 and achieved notable success at the bar. His son, john leycester adolphus (1794-1862), educated at Oxford, was a barrister and literary critic. He became a close friend of Sir Walter Scott. There was also an Adolphus family in America in the colonial period, founded by isaac (died 1774) who came to New York from Bonn, Germany, about 1750. Another family of this name was established in Jamaica not later than 1733, its most eminent member being Major General Sir jacob adolphus (1775-1845), inspector general of army hospitals.

ADONIM BEN NISAN HA-LEVI

(c. 1000), paytan and rabbi. Adonim, who served as a rabbi in Fez, Morocco, was among the first to use Arabic-Spanish metrics in his writings. Only a few of his piyyutim have survived, among them the lamentation "Bekhu, Immi Benei Immi"; the reshut to Parshat ha-HLodesh (see Special *Sabbaths) "Areshet Sefatenu Petah Ho-dayot"; and the selihot"Eli Hashiveni me-Anahah u-Mehumah" and "Roeh Yisrael Ezon Enkat Zonekha." His piyyutim excel in their fine poetic language and their originality. Several philosophical concepts which were discussed in intellectual circles in his days find expression in his works.

After the death of his brothers Amnon, Absalom, and, presumably, Chileab, Adonijah conducted himself as heir apparent (1 Kings 1:5-6). When David was on his deathbed, Adonijah attempted to seize power in order to forestall succession by *Solomon. In this he was supported by such veteran courtiers of David as *Joab and *Abiathar, and by many members of the royal family and the courtiers of the tribe of Judah (ibid. 7). Zadok the priest, Nathan the prophet, and others who had risen to prominence more recently, sided with Solomon (ibid. 8). Under Nathan’s influence, David ordered that Solomon should be anointed king in his own lifetime, in accordance with his promise to Bath-Sheba (ibid. 1off.). At first Solomon took no action against his brother (ibid. 50-53), but after David’s death, when Adonijah wished to marry *Abishag the Shunammite, his father’s concubine, Solomon correctly interpreted this as a bid for the throne and had him executed (ibid. 2:13ff.).

Other biblical figures of the same name were Adonijah a Levite who, with other Levites, priests, and princes, taught in the cities of Judah during the reign of Jehoshaphat (11 Chron. 17:8); and Adonijah, one of the leaders who signed the covenant in the days of Nehemiah (Neh. 10:17).

In the Aggadah

Adonijah was one of those who "set their eyes upon that which was not proper for them; what they sought was not granted to them; and what they possessed was taken from them" (Sot. 9b). The biblical verse "and he [Adonijah] was born after Absalom" (1 Kings 1:6) is interpreted to mean that, although the two were of different mothers, they are mentioned together since Adonijah acted in the same way as Absalom in rebelling against the king (bb 109b). The extent of his rebellion is illustrated in the aggadic tradition that he even tried the crown "the Lord / my Lord is exalted"), son of Abda.

ADONIRAM

(or Adoram, Hadoram; Heb. ![]()

![]() ram is described in a list of King David’s officials from the later years of David’s reign (11 Sam. 20:24) as the minister "in charge of forced labor." He continued in the same office during Solomon’s reign (1 Kings 4:6) and was in charge of the levy of all Israel sent to *Lebanon to cut lumber (1 Kings 5:27-28). During the first year of *Rehoboam, Adoniram was sent to face the discontented and revolting assembly at Shechem (12:1-19). The people, for whom he no doubt personified the detested corvee, stoned him to death (12:18). B. Mazar (Maisler) has suggested that Adoniram was of foreign origin, as the institution of forced labor was adopted by the Israelite monarchy from Canaanite patterns, and that it was only natural to appoint a Canaanite official as its head. The names of Adoniram and his father support the view of his Canaanite origin, since ad is synonymous with ab (av – father – in West-Semitic languages), while "Abda" is an abbreviated theophorical name found in Phoenician inscriptions. Some scholars believe that the lengthly tenure assigned by the Bible to Adoniram’s office is due to chronological confusion.

ram is described in a list of King David’s officials from the later years of David’s reign (11 Sam. 20:24) as the minister "in charge of forced labor." He continued in the same office during Solomon’s reign (1 Kings 4:6) and was in charge of the levy of all Israel sent to *Lebanon to cut lumber (1 Kings 5:27-28). During the first year of *Rehoboam, Adoniram was sent to face the discontented and revolting assembly at Shechem (12:1-19). The people, for whom he no doubt personified the detested corvee, stoned him to death (12:18). B. Mazar (Maisler) has suggested that Adoniram was of foreign origin, as the institution of forced labor was adopted by the Israelite monarchy from Canaanite patterns, and that it was only natural to appoint a Canaanite official as its head. The names of Adoniram and his father support the view of his Canaanite origin, since ad is synonymous with ab (av – father – in West-Semitic languages), while "Abda" is an abbreviated theophorical name found in Phoenician inscriptions. Some scholars believe that the lengthly tenure assigned by the Bible to Adoniram’s office is due to chronological confusion.

ADONI-ZEDEK

(Heb ![]() "[the god] Zedek [the god of justice] is lord" or, "my Lord is righteousness"), king of ^Jerusalem at the time of the Israelite conquest of Canaan (Josh. 10:1-3). Adoni-Zedek was the leader of a coalition to-gether with four of the neighboring *Amorite cities – Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish, and Eglon. The coalition was formed as a reaction to the conclusion of a covenant between the Israelites and the *Gibeonites as well as to the conquest of *Ai by the Israelites, who threatened the region and the sovereignty of the city-states over this area. The members of the coalition attacked Gibeon. The Gibeonites, however, solicited the aid of Joshua, who preferred to fight against the Amorites in an open area. The Amorites were defeated at Gibeon, and, finding no alternative route of escape, retreated to Beth-Horon where their pursuers routed them with the help of a hailstorm; the five allied kings hid in a cave at Makkedah but were found and killed. Nothing is said about the capture of Jerusalem, although its king had lost his life; a reduction of Jerusalem’s influence, however, did result from the war.

"[the god] Zedek [the god of justice] is lord" or, "my Lord is righteousness"), king of ^Jerusalem at the time of the Israelite conquest of Canaan (Josh. 10:1-3). Adoni-Zedek was the leader of a coalition to-gether with four of the neighboring *Amorite cities – Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish, and Eglon. The coalition was formed as a reaction to the conclusion of a covenant between the Israelites and the *Gibeonites as well as to the conquest of *Ai by the Israelites, who threatened the region and the sovereignty of the city-states over this area. The members of the coalition attacked Gibeon. The Gibeonites, however, solicited the aid of Joshua, who preferred to fight against the Amorites in an open area. The Amorites were defeated at Gibeon, and, finding no alternative route of escape, retreated to Beth-Horon where their pursuers routed them with the help of a hailstorm; the five allied kings hid in a cave at Makkedah but were found and killed. Nothing is said about the capture of Jerusalem, although its king had lost his life; a reduction of Jerusalem’s influence, however, did result from the war.

"Lord of the World"), rhymed

It is apparent that Jerusalem was an important city-state at the time, as is clear not only from this biblical passage but also from the *El-Amarna letters (14th century B.c.E.). Six of these letters, sent by the king of Jerusalem (Abdi-H epa) to the pharaoh of Egypt, warrant the conclusion that Jerusalem (and Shechem) controlled the hill country of Judah and Ephraim and ruled over "the land of Jerusalem" (Pritchard, Texts, 487-9). Adoni-Zedek is unknown from other sources, but he fits well into the above picture of pre-lsraelite Jerusalem. Some identify him with *Adoni-Bezek (Judg. 1:5-7), because the Septuagint reads Adoni-Bezek in place of the masoretic Adoni-Zedek.

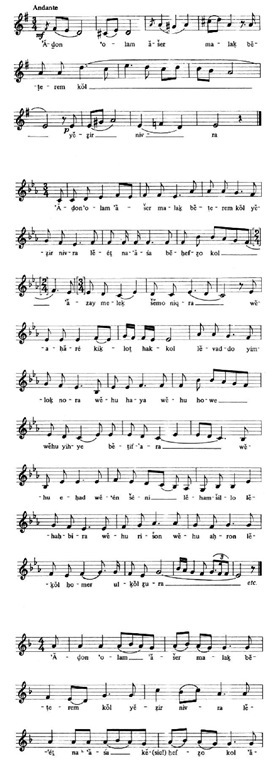

ADON OLAM

(Heb ![]() liturgical hymn in 12 verses (in the Ashkenazi rite) extolling the eternity and unity of God and expressing man’s absolute trust in His providence. The Sephardi rite has 16 verses. The author is unknown, though it has been attributed to Solomon ibn *Gabirol (11th century). It may, however, be much older and stem from Babylonia. The hymn has appeared as part of the liturgy since the 14th century in the German rite and has spread to almost every rite and community. It was incorporated into the initial section of the Shaharit Service, but it has been suggested on the basis of the penultimate line that it originally formed the conclusion of the Night Prayers where it also still appears. Its main place now is at the conclusion of the Sabbath and festival Musaf Service (with the Sephardim even on the Day of Atonement) and of the *Kol Nidrei Service. Adon Olam has become a popular hymn. In Morocco it serves as a wedding song and it is also recited by those present at a deathbed. The hymn has been translated several times into English verse, among others by George Borrow in his Lavengro (reprinted in Hertz, Prayer, p. 1005) and by Israel Zangwill (reprinted ibid., 7, 9), and into other European languages.

liturgical hymn in 12 verses (in the Ashkenazi rite) extolling the eternity and unity of God and expressing man’s absolute trust in His providence. The Sephardi rite has 16 verses. The author is unknown, though it has been attributed to Solomon ibn *Gabirol (11th century). It may, however, be much older and stem from Babylonia. The hymn has appeared as part of the liturgy since the 14th century in the German rite and has spread to almost every rite and community. It was incorporated into the initial section of the Shaharit Service, but it has been suggested on the basis of the penultimate line that it originally formed the conclusion of the Night Prayers where it also still appears. Its main place now is at the conclusion of the Sabbath and festival Musaf Service (with the Sephardim even on the Day of Atonement) and of the *Kol Nidrei Service. Adon Olam has become a popular hymn. In Morocco it serves as a wedding song and it is also recited by those present at a deathbed. The hymn has been translated several times into English verse, among others by George Borrow in his Lavengro (reprinted in Hertz, Prayer, p. 1005) and by Israel Zangwill (reprinted ibid., 7, 9), and into other European languages.

Music

Adon Olam is generally sung by the congregation. In the Ash-kenazi tradition it is also sometimes rendered by the cantor on certain festive occasions, and then the melody is adapted to the nosah of the section of the prayer into which it is incorporated. The great number of melodies for Adon Olam includes both individual settings, and borrowings from Jewish and Gentile sources. Ex. 3, from Djerba, is a North African "general" melody for piyyutim. Two versions from Germany in Idelsohn (Melodien, 7 (1932), nos. 59 and 336) both borrow the western Ashkenazi melody of Omnam Ken, while no. 346a is a German folk tune. A melody from Tangiers (I. Levy, Antologia, 1 (1965), no. 96) is the tune of the Romance Esta Rahel la estimoza. The composed or adapted tunes are mostly based upon a strict measure of four or three beats, both equally suitable for conforming to the hazak-meter of the text – one short and three longs. The melody is sung in many schools in Israel at the end of the pupils’ morning prayer (in 4/4 measure; cf. the same, in 3/4 measure, ye, vol. 1, p. 514). Salamone de’ *Rossi included an eight-voice composition of Adon Olam in his Ha-Shirim Asher li-Shelomo (Venice, 1622/23).

ADOPTION

Taking another’s child as one’s own. Alleged Cases of Adoption in the Bible

The evidence for adoption in the Bible is so equivocal that some have denied it was practiced in the biblical period.

(a) genesis 15:2-3. Being childless, Abram complains that *Eliezer, his servant, will be his heir. Since in the ancient Near East only relatives, normally sons, could inherit, Abram had probably adopted, or contemplated adopting, Eliezer. This passage is illuminated by the ancient Near Eastern practice of childless couples adopting a son, sometimes a slave, to serve them in their lifetime and bury and mourn them when they die, in return for which the adopted son is designated their heir. If a natural child should subsequently be born to the couple, he would be chief heir and the adopted son would be second to him.

(b) genesis 16:2 and 30:3. Because of their barrenness, Sarai and Rachel give their servant girls to Abram and Jacob as concubines, hoping to "have children" (lit. "be built up") through the concubines. These words are taken as an expression of intention to adopt the children born of the husbands and concubines. Rachel’s subsequent statement, "God… has given me a son" (30:6) seems to favor this view. A marriage contract from *Nuzi stipulates that in a similar case the mistress "shall have authority over the offspring." That the sons of Jacob’s concubines share in his estate is said to presuppose their adoption. Bilhah’s giving birth on (or perhaps "onto") Rachel’s knees (30:3; cf. 50:23) is believed to be an adoption ceremony similar to one practiced by ancient European and

Asiatic peoples among whom placing a child on a man’s knees signified variously acknowledgment, legitimation, and adoption. Such an adoption by a mistress of the offspring of her husband and her slave-girl would not be unparalleled in the ancient Near East (see J. van Seters, jbl, 87 (1968), 404-7), but other considerations argue that this did not, in fact, take place in the episodes under consideration. Elsewhere in the Bible the sons of Bilhah and Zilpah are viewed only as the sons of these concubines, never of the mistresses (e.g., 21:10, 13; 33:2, 6-7; 35:23-26). Rachel’s statement "God. has given me a son" reflects not necessarily adoption but Rachel’s ownership of the child’s mother, Bilhah (cf. Ex. 21:4, and especially the later Aramaic usage in Pritchard, Texts3, 548a plus n. 5). The concubines’ sons sharing in Jacob’s estate does not presuppose adoption by Rachel and Leah because the sons are Jacob’s by blood and require only his recognition to inherit (cf. The Code of Hammurapi, 170-1). Finally the alleged adoption ceremony must be interpreted otherwise. Placing a child on the knees is known from elsewhere in the ancient Near East (see I.J. Gelb et al., The Chicago Assyrian Dictionary, vol. 2 (1965), 256, s.v. birku; H. Hoffner, jnes, 27 (1968), 199-201). Outside of cases which signify divine protection and/or nursing, but not adoption (cf. T. Jacobsen, jnes, 2 (1943), 119-21), the knees upon which the child is placed are almost always those of its natural parent or grandparent. It seems to signify nothing more than affectionate play or welcoming into the family, sometimes combined with naming. (Only once, in the Hurrian Tale of the Cow and the Fisherman (J. Friedrich, Zeitschrift fuer Assyrio-logie, 49 (1950), 232-3 ll. 38ff.), does placing on the lap occur in an apparently adoptive context, but even there it is not clear that the ceremony is part of the adoption.) Some construe the ceremony as an act of legitimation, but no legal significance of any sort is immediately apparent. Significantly, the one unequivocal adoption ceremony in the Bible (Gen. 48:5-6) does not involve placing the child on the knees (Gen. 48:12 is from a different document and simply reflects the children’s position during Jacob’s embrace, between, not on, his knees). Furthermore, Genesis 30:3 speaks not of placing but of giving birth on Rachel’s knees. This more likely reflects the position taken in antiquity by a woman during childbirth, straddling the knees of an attendant (another woman or at times her own husband) upon whose knees the emerging child was received (cf. perhaps Job 3:12). Perhaps Rachel attended Bilhah herself in order to cure, in a sympathetic-magical way, her own infertility (cf. 30:18, which may imply that Rachel, too, had been aiming ultimately at her own fertility), much like the practice of barren Arab women in modern times of being present at other women’s deliveries. Genesis 50:23 (see below) must imply Joseph’s assistance at his great-grandchildren’s birth; or, if taken to mean simply that the children were placed upon his knees immediately after birth, it would imply a sort of welcoming or naming ceremony.

(c) genesis 29-31. It is widely held that Jacob was adopted by the originally sonless Laban, on the analogy of a Nuzi contract in which a sonless man adopts a son, makes him his heir, and gives him his daughter as a wife. This in itself is not compelling, but the document adds that, unless sons are later born to the adopter, the adopted son will also inherit his household gods. This passage, it is argued, illuminates Rachel’s theft of Laban’s household gods (31:19), and herein lies the strength of the adoption theory. But M. Greenberg (jbl, 81 (1962), 239-48) cast doubt upon the supposed explanation of Rachel’s theft, thus depriving the adoption theory of its most convincing feature. In addition, the Bible itself not only fails to speak of adoption but pictures Jacob as Laban’s employee.

(d) genesis 48:5-6. Near the end of his life Jacob, recalling God’s promise of Canaan for his descendants, announces to Joseph: "Your two sons who were born to you … before I came to you in Egypt, shall be mine; Ephraim and Manasseh shall be mine, as Reuben and Simeon are"; subsequent sons of Joseph will (according to the most common interpretation of the difficult v. 6), for the purposes of inheritance, be reckoned as sons of Ephraim and Manasseh. In view of the context – note particularly that grandsons, not outsiders, are involved – many believe that this adoption involves inheritance alone, and is not an adoption in the full sense. (M. David compares the classical adoptio mortis causa.) This belief is strengthened by the almost unanimous view that this episode is intended etiologically to explain why the descendants of Joseph held, in historical times, two tribal allotments, the territories of Ephraim and Manasseh.

(e) genesis 50:23. "The children of Machir son of Manasseh were likewise born on Joseph’s knees" is said to reflect an adoption ceremony. To the objections listed above (b), it may be added that unlike (d), Joseph’s adoption of Machir’s children would explain nothing in Israel’s later history and would be etiologically pointless.

(f) exodus 2:10. "Moses became her [= Pharaoh's daughter's] son." Some, however, interpret this as fosterage.

(g) leviticus 18:9. A "sister. born outside the household" could mean an adopted sister, but most commentators interpret it as an illegitimate sister or one born of another marriage of the mother.

(h) judges 11:1 ff. S. Feigin argued that Gilead must have adopted Jephthah or else the question of his inheriting could never have arisen. But since Jephthah was already Gilead’s son, the passage implies, at most, legitimation, not adoption.

(i) ruth 4:16-17. Naomi’s placing of the child of Ruth and Boaz in her bosom and the neighbors’ declaration "a son is born to Naomi" are said to imply adoption by Naomi. But the very purpose of Ruth’s marriage to Boaz was, from the legal viewpoint, to engender a son who would be accounted to Ruth’s dead husband (see Deut. 25:6 and Gen. 38:8-9) and bear his name (Ruth 4:10). Adoption by Naomi, even though she was the deceased’s mother, would frustrate that purpose. The text says that Naomi became the child’s nurse, not his mother. The child is legally Naomi’s grandson and the neighbors’ words are best taken as referring to this.

(j) esther 2:7, 15. Mordecai adopted his orphaned cousin Hadassah. (This case, too, is taken by some as rather one of fosterage.) This possible case of adoption among Jews living under Persian rule is paralleled by a case among the Jews living in the Persian military garrison at Elephantine, Egypt, in the fifth century c.e. (E. Kraeling, The Brooklyn Museum Aramaic Papyri (1953), no. 8).

(k) ezra 2:61 (= Nehemiah 7:63). One or more priests married descendants of Barzillai the Gileadite and "were called by their name." This may imply adoption into the family of Barzillai.

(l) ezra 10:44. Several Israelites married foreign women. The second half of the verse, unintelligible as it stands, ends with "and they placed/established children." S. Feigin, on the basis of similar Greek expressions and textual emendation, viewed this as a case of adoption. Since the passage is obviously corrupt (the Greek text of Esdras reads differently), no conclusions can be drawn from it, though Feigin’s interpretation is not necessarily ruled out.

(m) i chronicles 2:35-41. Since the slave Jarha (approximately a contemporary of David according to the genealogy) married his master’s daughter, he was certainly manumitted and, quite likely, was adopted by his master; otherwise, his descendants would not have been listed in the Judahite genealogy.

(n) In addition to the above possible cases, one might see a sort of posthumous adoption in the ascription of the first son born of the levirate marriage (Gen. 38:8-9; Deut. 25:6; Ruth 4) to the dead brother. The child is possibly to be called "A son of b [the deceased]"; in this way he preserves the deceased’s name (Deut. 25:6-7; Ruth 4:5) and presumably inherits his property.

summary. Of the most plausible cases above, two (a, d) are from the Patriarchal period, one reflects Egyptian practice (f), and another the practice of Persian Jews of the Exilic or post-Exilic period (j). From the pre-Exilic period there is a possible case alleged by the Chronicler to have taken place in the time of David (m), one or two other remotely possible cases (g) and (k), the latter from the late pre-Exilic or Exilic period) and the "posthumous adoption" involved in levirate marriage (n). The evidence for adoption in the pre-Exilic period is thus meager. The possibility that adoption was practiced in this period cannot be excluded, especially since contemporary legal documents are lacking. Nevertheless, it seems that if adoption played any role at all in Israelite family institutions, it was an insignificant one. It may be that the tribal consciousness of the Israelites did not favor the creation of artificial family ties and that the practice of polygamy obviated some of the need for adoption. For the post-Exilic per-iod in Palestine there is no reliable evidence for adoption at all.

Adoption as a Metaphor

(a) god and israel. The relationship between God and Israel is often likened to that of father and son (Ex. 4:22; Deut. 8:5; 14:1). Usually there is no indication that this is meant in an adoptive sense, but this may be the sense of Jeremiah 3:19; 31:8; and Hosea 11:1. (b) in kingship. The idea that the king is the son of a god occurs in Canaanite (Pritchard, Texts, 147-8) and other ancient Near Eastern sources. In Israel – which borrowed the very institution of kingship from its neighbors (1 Sam. 8:5, 20) – this idea could not be accepted literally; biblical references to the king as God’s son therefore seem intended in an adoptive sense. Several are reminiscent of ancient Near Eastern adoption contracts. Thus, Psalms 2:7-8 contains a declaration, "You are my son," a typical date formula "this day" (the next phrase, "I have born you," may reflect the conception of adoption as a new birth), and a promise of inheritance (an empire); 11 Samuel 17:7 contains a promise of inheritance (an enduring dynasty), a declaration of adoption, and a statement of the father’s right to discipline the adoptive son (cf. Ps. 89:27 ff.; 1 Chron. 17:13; 22:10; 28:6).

Since the divine adoption of kings was not known in the ancient Near East, and the very institution of adoption was rare – if at all existent – in Israel, the question arises as to where the model for these metaphors was found. According to M. Weinfeld (jaos, 90 (1970)) the answer is found in the covenants made by God with David and Israel. These are essentially covenants of grant, a legal form which is widespread in the ancient Near East. In some of these a donor adopts the donee and the grant takes the form of an inheritance. Thus in the biblical metaphor God’s adoption of David serves as the legal basis for the grant of the dynasty and empire, and God’s adoption of Israel underlies the grant of a land (Jer. 3:19; also noted by S. Paul). According to Y. Muffs, the pattern of the covenant in the Priestly Document (p) is modeled on adoption by redemption from slavery (cf. Ex. 6:6-8). In later times adoption was used metaphorically in the Pauline epistles to refer variously to Israel’s election (Rom. 9:4), to the believers who were redeemed from spiritual bondage by Jesus (Rom. 8:15; Eph. 1:5; Gal. 4:5), and to the final eschatological redemption from bondage (Rom. 8:21-23). Whether Paul modeled the metaphor on biblical or post-biblical, ancient Near Eastern, or Roman legal sources is debated.

Later Jewish Law

Adoption is not known as a legal institution in Jewish law. According to halakhah the personal status of parent and child is based on the natural family relationship only and there is no recognized way of creating this status artificially by a legal act or fiction. However, Jewish law does provide for consequences essentially similar to those caused by adoption to be created by legal means. These consequences are the right and obligation of a person to assume responsibility for (a) a child’s physical and mental welfare and (b) his financial position, including matters of inheritance and maintenance. The legal means of achieving this result are (1) by the appointment of the adopter as a "guardian" (see *Apotropos) of the child, with exclusive authority to care for the latter’s personal welfare, including his upbringing, education, and determination of his place of abode; and (2) by entrusting the administration of the child’s property to the adopter. The latter undertaking to be accountable to the child and, at his own expense and without any right of recourse, would assume all such financial obligations as are imposed by law on natural parents vis-a-vis their children. Thus, the child is for all practical purposes placed in the same position toward his adoptors as he would otherwise be toward his natural parents, since all matters of education, maintenance, upbringing, and financial administration are taken care of (Ket. 101b; Maim., Yad, Ishut, 23:17-18; and Sh. Ar., eh 114 and Tur ibid., Sh. Ar., hm 60:2-5; 207:20-21; pdr, 3 (n.d.), 109-125). On the death of the adopter, his heirs would be obliged to continue to maintain the "adopted" child out of the former’s estate, the said undertaking having created a legal debt to be satisfied as any other debt (Sh. Ar., hm 60:4).

Indeed, in principle neither the rights of the child toward his natural parents, nor their obligations toward him are in any way affected by the method of "adoption" described above; but in fact, the result approximated very closely to what is generally understood as adoption in the full sense of the word. The primary question in matters of adoption is the extent to which the natural parents are to be deprived of, and the adoptive parents vested with, the rights and obligations to look after the child’s welfare. This is in accordance with the rule that determined that in all matters concerning a child, his welfare and interests are the overriding considerations always to be regarded as decisive (Responsa Rashba, attributed to Nah manides, 38; Responsa Radbaz, 1:123; Responsa Samuel di Modena, eh 123; Sh. Ar., eh 82, Pithei Teshuvah 7).

Even without private adoption, the court, as the "father of all orphans," has the power to order the removal of a child from his parents’ custody, if this is considered necessary for his welfare (see *Apotropos). So far as his pecuniary rights are concerned, the child, by virtue of his adopters’ legal undertakings toward him, acquires an additional debtor, since his natural parents are not released from their own obligations imposed on them by law, i.e., until the age of six. Furthermore, the natural parents continue to be liable for the basic needs of their child from the age of six, to the extent that such needs are not or cannot be satisfied by the adopter; the continuation of this liability is based on Dinei Zedakah – the duty to give charity (see *Parent & Child; pdr, 3 (n.d.), 170-6; 4 (n.d.), 3-8).

With regard to right of inheritance, which according to halakhah is recognized as existing between a child and his natural parents only, the matter can be dealt with by means of testamentary disposition, whereby the adopter makes provision in his will for such portion of his estate to devolve on the child as the latter would have gotten by law had the former been his natural parent (see Civil Case 85/49, in: Pesakim shel Beit ha-Mishpat ha-Elyon u-Vattei ha-Mishpat ha-Mehoziyyim be-Yisrael, 1 (1948/49), 343-8). In accordance with the rule that "Scripture looks upon one who brings up an orphan as if he had begotten him" (Sanh. 19b; Meg. 13a), there is no halakhic objection to the adopter calling the "adopted" child his son and the latter calling the former his father (Sanh. ibid., based on 11 Sam. 21:8). Hence, provisions in documents in which these appellations are used by either party, where the adopter has no natural children and/or the child has no natural parent, may be taken as intended by the one to favor the other, according to the general tenor of the document (Sh. Ar., eh 19, Pithei Teshuvah, 3; hm 42:15; Responsa Hatam Sofer, eh 76). Since the legal acts mentioned above bring about no actual change in personal status, they do not affect the laws of marriage and divorce, so far as they might concern any of the parties involved.

In Israel

In the State of Israel, until 1981, adoption was governed by the Adoption of Children Law, 5720/1960, which empowered the district court and, with the consent of all the parties concerned, the rabbinical court, to grant an adoption order in respect of any person under the age of 18 years, provided that the prospective adopter was at least 18 years older than the prospective adoptee and the court were satisfied that the matter was in the best interests of the adoptee. Such an order had the effect of severing all family ties between the child and his natural parents. On the other hand, such a court order created new family ties between the adopter and the child to the same extent as are legally recognized as existing between natural parents and their child – unless the order was restricted or conditional in some respect. Thus, an adoption order would generally confer rights of intestate succession on the adoptee, who would henceforth also bear his adopter’s name. However, the order did not affect the consequences of the blood relationship between the adoptee and his natural parents, so that the prohibitions and permissions of marriage and divorce continued to apply. On the other hand, adoption as such does not create such new prohibitions or permissions between the adopted and the adoptive family. There was no legal adoption of persons over the age of 18 years.

In 1981 the Knesset repealed the Adoption of Children Law, 5720/1960 and enacted in its stead the Adoption of Children Law, 5741/1981 (hereinafter – the Law), empowering the Family Court to issue adoption orders. The Law and its subsequent amendments provide for two substantively different modes of adoption. The first is local adoption, in which the Child Welfare Authority – a branch of the Welfare Ministry – functions as an adoption agency: it determines the adoptive parents’ eligibility and even initiates adoption proceedings of the minor in the court, by way of special welfare officers for adoption. Proceedings to declare a minor adoptable can only be initiated by these welfare officers. The Child Welfare Authority is similarly responsible for the removal of a child from the custody of his natural parents against their wishes, for purposes of adoption. Occasionally, and under special circumstances, even prior to the child being declared adoptable the Authority may hand over the child "to a person who has agreed to receive him into his house with a view to adopting him" (§12 (c) of the Law). The second mode is that of "intercountry" (i.e., international) adoption, in which the adoption is undertaken by non-profit organizations under the supervision of a "central authority" i.e., the Child Welfare Authority.

The difference between the two kinds of adoption is as follows: local adoption also involves numerous cases in which the biological parents do not consent to hand their child over for adoption, in which case, quite naturally, the identity of the adoptive parents is withheld (closed adoption) to protect the adopted child from potential harm at the hands of his natural parents. In international adoption, the adoption is the product of negotiations between the prospective adoptive parents and the natural family. Under the Law, the rabbinical court is also permitted to issue adoption orders with the consent of all the parties, i.e., the parents (or adoptive parents, respectively) and the minor (when the case concerns a minor above the age of nine) or with the consent of the attorney general (in cases of a minor below nine). Even in those cases in which the rabbinical court has jurisdiction pursuant to the parties’ consent, it is nevertheless obliged to comply with all the provisions of the law (§27).

The arrangements for international adoption were transformed when the law was amended in 1996, in accordance with the format of the Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption, which Israel ratified in 1993. Together with the incorporation of the Convention’s provisions in the Law, the legislature also addressed a particular problem, unique to the State of Israel by virtue of its Jewish character. Under section 5 of the Law: "The adopter shall be of the same religion as the adoptee." How then can a Jewish family receive an adoption order for a non-Jewish child, brought to Israel from abroad? The legislature resolved this problem by amending section 13A of the Capacity and Guardianship Law, 5722/1962, which now provides that the court may give an instruction for the minor’s religious conversion "to the religion of the person who provided for the minor with the intention of adopting him, during the six months that preceded the filing of the application for conversion."

In addition to the court’s authorization, the minor who is a candidate for adoption must undergo a conversion process; according to the halakhah, a minor who is to be converted must be ritually immersed for conversion through the authority of the bet din. This is so, "because it [the conversion] is a benefit to him" (Ketubot 11a). The Israeli rabbinical courts have avoided converting minors who are candidates for adoption when the prospective adoptive parents will not provide him/ her with an education based upon religious observance.

The case law of the Israel Supreme Court on adoption (given by Deputy President Menachem *Elon) emphasized the extensive impact of Jewish law on actual adoption procedures. The Law provides that "the adoption shall not affect any legal prohibition or permission as to marriage or divorce" (§16(c)); accordingly, the Adoption Register may be inspected by a marriage registrar in the course of carrying out his official function (§30 (2)). In doing so he raises the legal "veil" separating the adopted child from his natural family in order to establish the "legitimacy of his pedigree"; in other words, to prevent marriages between a brother and sister, etc. Furthermore, an adoption performed "for the benefit of the adoptee" does not represent the optimal solution, and preference should be given to the other arrangements, which do not sever the child from his natural family, despite their defective parental capacity. "Adoption is not intended as a punishment for the natural parents, we punish by confiscating property; we punish by denying freedom, but we do not punish by taking children away" (c.A. 3063/90 p.D. 45 (5) 837, 848), save for cases in which there is unequivocal, objective proof that the parents are incapable of raising their children.

As a rule, there is no discussion of the "child’s best interests" until after examination as to whether there is any statutory ground for "removing the child from the natural guardianship of his parents and placing him in the home of the adopters" (h.c. 243/88 Konsols v. Turgeman, 45 (5) p.D. 837, 848). For the same reason, all possible efforts should be made to avoid ordering that the adoption of the minor be a "closed" adoption, which separates the minor from his natural identity. Indeed, in its capacity as the "father of minors," the court is commanded to "ensure the welfare and the future of the minor" and order that he be severed from his natural family -but this, only done when the court is convinced that leaving the minor with his family, or placing him with a foster family or in an "open adoption" will cause him terrible suffering due to his parents’ incompetence (Elon, in the following judgments: c.A. 310/82, 37 (4) p.D. 421; c.A. 3763/92, 47 (1) p.D. 869). Similarly, the court will order the Child Welfare Service to seriously consider a request from the natural family that their child be given to "a family belonging to their own religious community, that maintains a religious lifestyle" (c.A. 3063/90 45 (3) 837) and, in exceptional circumstances, consider assenting to the parents’ request that their child be adopted by their relatives who have no children of their own. This is in accordance with the prevalent custom in a number of Jewish communities whereby "when a couple belonging to the extended family is childless, another couple in the family, blessed with children, gives one of them to the couple that was denied their own offspring, and the latter can adopt and raise the child, as if he was their own child" (c.A. 568/80 35 (3) 701, 702).

Where the question arose of severing an adoptee minor from the religion of his natural parents, Justice Elon raised another consideration for withholding authorization of an adoption performed against the natural parents’ wishes, or with their coerced consent: "We remember the battles fought by Jewish families and institutions in order to restore Jewish children to their families and religion. Prior to being sent to the death camps and gas chambers these families placed their children with Christians to care for them and raise them. It is befitting that we emulate their conduct in similar situations, when the tables are turned and the context is no longer the death camps but rather gangs of avaricious criminals" (the case of the "Brazilian girl" who was abducted from her natural mother; h.c. 243/88, 45 (2) p.D. 652).

In describing the character of the institution of adoption, its interpretation and implementation by the Israeli judiciary, Justice Elon further stated:

I wholeheartedly agree that we must not hinder the development of the institution of adoption, having regard primarily for its crucial importance in locating a warm and secure home and a loving, devoted family for children who have suffered at the hands of fate. In pursuing this important goal we must also ensure the totality of the adoptive parents’ rights and obligations in their relations with the adopted child. However, we must not ignore our principal and basic obligation, which is to maintain, promote and preserve the earliest and most fundamental social unit in human history: the natural family, its descendants, offshoots and progeny, the unit which always has, does, and always will continue to guarantee the survival of human society. This is certainly the case when dealing with the history of the Jewish family, in which the family unit, in both the immediate and extended sense, was the central pillar that guaranteed Jewish survival and continuity. This principle applies a fortiori in our times, in which the institution of the natural family has encountered tumultuous upheavals and frequent crises, which have weakened its capacity to function. (c.A. 488/77, 32 (3) p.D. 421 434)

And, in another decision:

Tearing a child away from his biological parents is more difficult than splitting the Red Sea. The same applies to all decisions concerning a minor’s adoption; all the more so in a case such as the one confronting us, in which the children are no longer infants and know their parents and their siblings. But as a court that is the "father of all minors," it is our responsibility to ensure their welfare and their best interests. It is incumbent upon us to find them a home in which they will merit love and warmth, physical well-being and spiritual tranquility, and all of the basic, elementary needs that they are not receiving in the home of their biological parents. (c.A. 658/88, 43 (4) p.D. 468, p. 477) by the Rabbinical Court for a Minor, in accordance with the Halakhah," in: Shurat ha-Din (2000), 475; A.J. Goldman, Judaism Confronts Contemporary Issues (1978), 63-73; Y. Rosen, "Giyyur Ketinim ha-Me’umazim be-Mishpahah Hlillonit," in Tehumin, 20 (2000), 245; M. Steinberg, Responsum on Problems of Adoption in Jewish Law (1969); I. Warhaftig, Av u-Veno, Mehkarei Mishpat, 16 (2000), 479; R. Yaron, "Variations on Adoption," in: Journal of Juristic Papyrol-ogy, 15 (1965), 171-83.